James Montgomery, my father’s 5x great grandfather, was titled ‘Gentleman’ and was a member of a prominent Scottish clan in Northern Ireland. He was born around 1695 in County Donegal. According to family lore he was closely related to General Richard Montgomery who died at the storming of Quebec in 1775, nearly a century later. I am usually dubious when folks try to connect their bloodlines to famous names in history especially when D.B. himself has declared the issue null and void. However, the source for this claim was the Honorable Senator John C. Calhoun (1782-1850), the South Carolina statesman who helped plunge the nation into the American Civil War. I think it is fair to question the Senator’s claim in light of D.B.’s findings. It is also fair to wonder if there was more than one man, named James Montgomery, 4 wheeling through the hills of Augusta County VA. Editor’s Note: You do realize that you have used an oxymoron, ‘Honorable Senator,’ in that last paragraph? You have violated ‘Rule 41b paragraph 3’ which prohibits the use of any literary device to make a family genealogy interesting. Author’s Response: My apologies, I couldn’t help myself. According to The Draper Papers, authored by Dr. Lyman C. Draper, Captain James Montgomery fought a duel in Ireland and had to flee Ireland to Scotland. He married Anne Thomson, a relative of the famous Scottish poet, James Thomson of Roxburgh, author of The Seasons. In 1746 Captain James was living near the Chestnut Level Presbyterian Church, on Fishing Creek in Dromore Township in Lancaster County. He sent his sons, Robert and John, to investigate land in Augusta County, Virginia. Robert purchased 654 acres on Catawba Creek in Benjamin Borden’s Middle Tract for the price of “20 English pounds and two uncommon large bells” from a Pennsylvania ironworks. The transaction was noted in Deed Book Number 1, Augusta County Virginia, page 123. “19 June 1746: Zeruiah Borden, widow and Benj. Borden Jr, of Augusta, executors of Benj. Borden, late of Orange to James Montgomery, 20 pounds current money Virginia; 654 acres, part of 3553 acres patented to Benjamin, Sr., 9th March 1740.” The Montgomery family purchased the property on Catawba, agreeing to provide Borden with those “two uncommonly large bells” as partial payment for the land. The Montgomery men returned to Pennsylvania, secured the two large bells and brought the remainder of their families to Augusta County. Catawba Creek is in the eastern Appalachian Mountains, in a valley just northwest of the Blue Ridge Mountains. The Catawba joined with the upper reaches of the James River at the eastern boundaries of the Montgomery farm in what was considered Borden’s Middle Tract. The Catawba Valley and the bottom land along the James behind Purgatory Mountain attracted many explorers, visitors, and settlers. Benjamin Borden, Jr was the son of Benjamin Borden Sr (1675-1743), a land speculator who played a significant role in establishing early settlements west of the Blue Ridge Mountains. A native of New Jersey, the senior Borden moved into the Shenandoah Valley in 1734 and began receiving patents for large landholdings. He raised tobacco and lived in the valley until his death in 1743. Senior acquired over 100,000 acres via a headright system that granted him 1000 acres for every family he could lure into the upper part of the Shenandoah Valley, along the branches of the James River. Borden promoted settlements, notably attracting newcomers from Ireland and Scotland to his properties. There is no record of land owned by Europeans in that region prior to the patent established by Borden. His first residents included John McFarrin, James Montgomery, James Davis and Bryan McDonald. Others of our great grandparents, the Ushers, Pullens, and Cooks lived just over the ridge in settlements along lesser tributaries of the James known as Cowpasture and Bullpasture Creeks. The Catawba River was named after the Catawba Indians of North Carolina who lived along the waterway. These Natives used the banks of the river as part of their trail from the Carolinas through Virginia into Pennsylvania. During the early Eighteenth Century, the Scot Irish settlers moving south along the river encountered a number of Catawba Indian villages. These ancient Native trails ran directly across the farmland bought by James Montgomery near present day Fincastle VA. Looney’s Ferry, which early settlers used to cross the James River, was but a few miles to the east of the James Montgomery homestead. The present day, Looney Mill Creek park, is a prehistoric and historic archaeological site near Buchanan VA. Evidence of Native American occupation dating as far back as 6000 BC, has been unearthed on the site. The mill was established circa 1742 by Robert Looney, one of the area’s first European settlers. Augusta County records indicate that James Montgomery was active in the Shenandoah as early as 1746. He served as a justice of the Augusta County Court, a Militia Captain and an Officer of the New Derry Presbyterian Congregation. Augusta County was carved out of Orange County in 1738. An order of the 1745 Orange County Court directed George Robinson and Simon Akers to survey the construction of a local road from the Forks of the Roanoke to the gap over the mountains from the Catawba. The Augusta County Court then appointed Mark Evans, William Kervine, John McFarran and James Montgomery to be overseers of that road. James Montgomery and George Robinson were to notify the Lunenberg County Court that a road had been built in Augusta from the Roanoke to the top of the Blue Ridge adjoining Lunenburg. Montgomery asked theLunenburg County Court to continue the construction of that road to the southeast. Lunenburg County encompassed a vast area and the road, when completed would allow access to the Shenandoah from the east and south. The area to the south, known as Southside Virginia, had been previously surveyed and explored by James Pittillo (1690-1754). A Scot rebel from Logierait, Perthshire, Pittillo had participated in the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715 and for that reason was deported by the British crown. Pittillo is a 6th great grandfather in my wife’s family tree. He rose from his status as an indentured servant in Prince George County VA to become a major player in the Virginia economy, owning more than 4000 acres of valuable farmland replete with plantations in various locations. An early judgment in the Augusta County Court rendered in the matter of Brown vs. Smith (Aug. 1747) notes the July 15th testimony of, “Captain James Montgomery, gent, living at the Catawba prior to 15th July 1747.” I have not pursued the facts of the case. Neighbors of James Montgomery are identified in deeds from that decade and include: James and Thomas Peevie, planters, John Campbell, William McNabb, John Lynn, Thomas Henderson, Thomas Rutlidge, Robert Ramsey. and Thomas Kirkpatrick. A 1749 transaction involving the vast landholdings of William Beverley further identified original settlers and significant names in early American history: James Patton, John Lewis, John Buchanan, George Robinson, Peter Scholl, James Bell, Robert Campbell, Robert Cunningham, John Wilson, Thomas Lewis, James Montgomery, Silas Hart, Henry Downs, William Jameson, Richard Burton, John Christian, Samuel Gay, and William Thompson. Many of these surnames appear in the annals of American history. James Patton, as one example, was a many times great grandfather of General George Patton. General Patton also descended from the marriage of Ann Pittillo and James Williams, as does my wife. The general and my wife share James and Ann Williams as 5 times great grandparents. Anne was the daughter of James Pittillo. The history of John Lewis (1678-1762) and his brothers in both Donegal, Ireland and Augusta County VA is an incredible tale of heroic strength and rebellion. Lewis displayed sizable entrepreneurial skills as he accumulated wealth in Virginia while working his ass off. The gravestone of Lewis tells a shortened version of his journey: “Here lie the remains of JOHN LEWIS, who slew the Irish Lord, settled Augusta County, located the Town of Staunton, and furnished five sons to fight the battles of the American Revolution. He was the son of Andrew Lewis and Mary Calhoun and was born in Donegal County, Ireland in 1678, and died Feb’y lst, 1762, aged 84 years. He was a true patriot and a friend of liberty throughout the world. Mortalitate Relicta Vivit Immortalitate Inductus.” (Mortality remains alive, immortality follows.) James Montgomery’s sister Catherine had married Patrick Calhoun. They became the grandparents of Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina who was also elected Vice President of the United States (1825-1832) serving under Presidents John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. Patrick’s aunt, Mary Calhoun (Catherine’s sister), had married Andrew Lewis. The party was just getting started, but sadly enough for sister Catherine it soon ended in bloodshed. We will come back to that tragedy. In April of 1751 the deed books indicate that James Montgomery sold his 654 acres of land back to Benjamin Borden Junior. One-month later Borden sold the same property to James’ son, Robert Montgomery. The reason the property had to go through the hands of Benjamin Bordern is unclear. It may be assumed that Borden controlled all transactions within the domain of his father’s original patent; then again, perhaps not. The question arises as to the role James’s wife played in the transaction. There is no evidence that she exercised or had the opportunity to exercise her right of dower. On December 11,1749, James Montgomery was listed as the executor for the Last Will and Testament of Samuel Crockett in Augusta County, Virginia. Samuel Crockett’s wife Esther Thompson was the daughter of the aforementioned William Thompson in the Catawba Creek neighborhood and sister of Ann Montgomery nee Thomson, the wife of James Montgomery. Samuel Crockett was a forefather of the heroic Davey Crockett of Alamo fame. Cue my mantra: It’s a small world. Our ancestors are all interconnected, six steps removed from Kevin Bacon. We are all one. ‘I am the Walrus. Goo goo ga j’boob.’ Editor’s Note: I hope you realize the Beatles sang “I am the Walrus” a half century ago, long before nieces and nephews were born…… They are going to think you have completely lost it! Author: The hell you say! Am I getting that old? Seems like yesterday. ‘Yesterday, all my troubles seemed so far away….’ Editor: You are wandering. Author: I could give a rat’s patoot…. In May 1754, James Montgomery acquired two properties: 54 Acres on the north side of the James River and 80 Acres on both sides of the James. The year was important in American history as it marked the beginning of what we refer to as the ‘French and Indian War’. Pioneers along the Blue Ridge were under attack from Native forces aligned with the French seeking to contain British Colonial America to the east of the Appalachian Mountains. Initial attacks forced the Montgomery family to remove themselves to the safety of a fortress established in Bedford VA. In 1756, James and his family again tried to live on his land along the James River. Native forces attacked again. As Captain of the militia, James was prepared for war and this time did not retreat to Bedford. James Montgomery sealed his fate as he gave the order to counterattack. He and 12 other people were killed defending Fort Dinwiddie, a Jackson River settlement. Twenty-eight people, mostly children, were carried away by the tribal forces. Many of those kidnapped were never seen again. In 1764 American militia forced the Natives to return 32 men and 58 women of Virginia to their homesteads. Contrary to preconceived notions as to how whites were treated when enslaved by Natives, many of the folks returning indicated they were made to feel like family, treated very warmly and well fed and clothed by the Native captors. Several returned to live in their Native communities. While he was a prominent man in the Catawba Community, James died destitute in 1756. On Nov 19, 1756 his widow, Anne Montgomery, with John Dickenson and James Simpson, posted bond to administer his estate which was appraised on March 16, 1757, and his debts noted. Shortly afterwards, in the latter months of 1757, Anne Montgomery moved with her youngest son Joseph (age 23), to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. A historian, Oral Montgomery, in his collection, Montgomery Heritage, speculates that Anne was moving home to find support from her son Samuel Montgomery, who apparently had remained in Lancaster. James Kegley, Virginia Frontier, agrees that Anne returned to Lancaster PA. This Lancaster connection becomes increasingly important as this story continues to unfold. The Augusta County Deed Book XIV reveals the following transaction: “By deed dated October 17, 1765, Patrick Calhoun of the Long Cane Settlement in the County of Granville of the Province of South Carolina, Jr, conveyed to Hugh Montgomery, late of the Parish and County of Augusta in Virginia, in consideration of 300 current money of Virginia, 610 acres of land on Reed Creek and on a branch thereof in the said Parish and County.” Witnesses: Jno. Poage, Robert Anderson and Thomas Poage. Hugh Montgomery’s wife was Caroline Anderson. Her father and her brother were each named Robert Anderson. Her father passed away early in the 18th Century. The witness to the Reed Creek sale was likely her brother Robert. The son of James Montgomery, Robert Montgomery, moved to Reed Creek, Botetourt County VA and in September of 1771 he purchased 500 acres of creek bottom land from his cousin John Calhoun of the Long Cane Settlement in South Carolina. He paid five shillings and sold the lands in December of ‘71 to his sons, James and William Montgomery, for 100 pounds Virginia currency. Quite a quarterly return on the investment! Robert sold the original James Montgomery homestead on the Catawba to William Christian in 1781 and in the next year Christian sold to Jacob Carper. Carper sold to James Breckenridge in 1794. Breckenridge incorporated the land into his magnificent Grove Hill Estate. The Breckinridge family became a political force in Virginia, Kentucky and the United States Congress. They then threw everything to the wind, committed treason and joined the Confederate States of America in 1860. General Breckinridge would occasionally shine as a Confederate leader when his blood alcohol levels permitted rare hints of sobriety. Act II, Scene 1: With James dead, what does Anne do next? Little is known about Edward Tarr the child. He may have been born circa 1711 to parents somewhere in the world. His first known master was Andrew Robeson in Schuylkill Falls PA in 1734. Robeson died in 1740 and Tarr was purchased by John Hansen, a highly skilled ironworker of some renown. Tarr acquired blacksmith skills in his younger days and proved to be invaluable to Hansen. Hansen’s records indicate that Hansen ran a highly efficient operation and profitable. Both Hansen and Robeson recorded observations of Tarr’s character and intelligence. They noted that Tarr was very fluent in English and German and literate in both languages as well. They also noted that Edward was well versed in the Bible and a firm believer in the Christian tenets. I should note that much of what I have learned about Edward Tarr has been gleaned from the work of Turk McCleskey, a University of Virginia professor whose research consumed two decades of his life. Tarr’s remarkable life is captured in a book you will find up on my shelf: The Road to Black Ned’s Forge. In the summer of 1745 Edward Tarr was owned by Thomas Shute. In a fortunate turn of events for Edward, Shute died in 1748. The slave-master stipulated in his will that Tarr could purchase his freedom following Shute’s death, in a manner prescribed by Shute. Having had the opportunity to earn money over the years with incentives offered by Hansen, Tarr purchased his freedom by making 6 annual installment payments over the course of 6 years. Tarr married a white Scottish wife, not our Anne Montgomery, and moved to Virginia and established his career as an independent blacksmith. Tarr purchased 270 acres of land from Jacob Peck, a descendant of Reverend Robert Peck of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and a many time great grandfather in my wife’s tree. The property was at the center of the Timber Ridge Parish and situated right on the Great Wagon Road that wiggled its’ way through the woodland, connecting Philadelphia to the Carolinas. The road cut through the center of Tarr’s land and he was able to locate his blacksmith shop right square in front of the eyes of any wagon master in need of maintenance. Tarr understood the first rule of setting up shop: ‘Location, location, location.’ With the purchase he became the first free black landowner west of the Blue Ridge. Tarr’s neighbor, Robert Huston, had set aside land for the construction of the Timber Ridge Church in which Tarr fervently worshipped with friends and neighbors. The Huston’s were Scot Irish who had come into the valley from Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Esther Houston, a daughter of John and sister to Robert Houston, married Robert McFarland in Lancaster. Robert McFarland is my father’s 4th great grandfather. Robert’s daughter, Mary Polly McFarland, married our Samuel Montgomery (1743-1815), my father’s 3rd great grandfather who died in Gibson County, Indiana. The Houstons were forerunners of Samuel Houston, of Alamo fame, for whom the city in Texas is named. Tarr’s status as a property owner was very important to his future success, when attempts were made to cast him back into slavery. He also carried the paperwork that insured inspectors that he was indeed a freeman. He was a ‘free landholder’ not just a ‘freeman.’ This was important in colonial society. With land came power. There were some in Augusta who owned larger estates than Edward Tarr, and many who owned less acreage. His possession of 270 acres was in the median range. White men with similarly sized properties were entitled to vote, participate in government and allowed rights and privileges not extended to men with lesser amounts of land. Edward was not white and not allowed the entitlements accorded the white guys who owned an equal amount of land. Tarr had arrived in the Shenandoah in 1753, just as Native forces began clashing with colonial militias. Tarr and his wife soon returned to the safer environs of Lancaster County PA. It is not clear if he did so in the company of Anne Montgomery and her son. Nor is it clear if Anne Montgomery was with the Tarr family in Lancaster. The Tarrs and Anne Montgomery were all in Lancaster during the same brief two-year period. Tarr’s already dramatic story took a perilous turn when he returned to his home in the Shenandoah. The son of Thomas Shute, Joseph, had established a branch of his father’s mercantile business in Charleston, South Carolina. Unlike his father, who had become a successful venture capitalist, Joseph Shute floundered in his attempt to create wealth and he showed a propensity for bankruptcy, long before it became fashionable for American presidents to boast of numerous bankruptcies. Joseph Shute’s illegal and immoral activities are documented in the archives of South Carolina and Pennsylvania. His failed attempts left him scheming and engaged in predatory behavior. Great Grandfather Hugh Montgomery and Edward Tarr In 1657, Joseph Shute sold Hugh Montgomery, my father’s 4th great grandfather, the rights to own Edward Tarr. Joseph Shute did not have the right to sell Edward Tarr to anyone. Joseph Shute did not own Edward Tarr. He held no title to Tarr. Tarr had legally purchased his freedom in Pennsylvania and the Shute family had, per the will of Thomas Shute, relinquished their ownership of the man. Tarr’s fate suddenly hinged on the will of his neighbors, who were all that stood between Tarr and a return to the life of a slave. Tarr had become an integral part of a very white community. Per McCleskey’s account, Tarr: “set himself up in the middle of this white community, married to a Scottish woman, a white woman, living in plain sight in what we think of as a very racist colony in the Colonial era.” Tarr’s neighbors accepted his interracial marriage. In fact, Tarr’s reason for moving from Pennsylvania to Virginia was considered a legally sound move in 1752. While a black man could not marry a white woman in Virginia, the colony recognized the importance of the rule of the law. If an interracial couple had been legally married in another colony or nation, they had the right to live together in Virginia. But Tarr made what some neighbors considered a serious mistake. He and his wife brought Anne Montgomery into their home to live, sans children. Eyebrows were raised, gossip flared in some quarters and the arrangement was viewed as over the top. Neighbors were alarmed by what appeared to be a love triangle under one roof. Tarr moved his family of three to Staunton VA, where he set up again as a blacksmith and continued to live with the two women. Calling upon McCleskey again: “This is an extremely orderly frontier. They all believed in the rule of law. They punished inappropriate sexual behavior, but they didn’t punish Tarr. They defined him as an exception for a reason. When we start looking around Virginia, including Eastern Virginia we find people like Tarr who were people of color and yet were free and represented a small but visible exception to slavery. They become their own kind of community in this late Colonial period, and in some ways are able to put some distance between themselves and slaves.” Tarr’s unique life story was almost brought to an untimely end. When Hugh Montgomery presented his bill of sale to the Augusta court he fully expected to leave with Edward Tarr in his custody. Hugh had been a resident of Augusta County in 1753. One of Edward’s neighbors had sued Hugh Montgomery one pound and nine shillings for a steer Hugh had purchased. Montgomery was nowhere to be found. The summons to appear in court to answer the charge brought against him could not be served. Hugh Montgomery, like many citizens of Augusta chose to leave the stress of Native warfare for a calmer environment in Charleston SC. His debt went unpaid. Folks who identify Hugh Montgomery as a great grandfather point to the fact that his five sons fought for the cause of freedom in the Revolutionary War. Many of Hugh’s descendants file their applications for membership in honored clubs like the Daughters of the American Revolution. They proudly point to Hugh Montgomery as their iconic hero. He was far from that. In 1757 Hugh operated an ordinary (a tavern) in Salisbury NC. In 1758 he took on a large loan for purchases made in Perquimans County NC. The following year (March 1759) he amassed an even larger debt purchasing goods on credit of 2079 dollars (SC currency) in Charleston SC. In May of 1759 he borrowed another 2,604 dollars for the purchase of merchandise and slaves. Hugh slipped away from the Carolinas and left his debts unpaid. He retreated into Augusta County where he dabbled in providing beef cattle to the standing militias who defended the Virginia frontier. In October of 1761 he appeared before a magistrate court and sought the magistrate’s permission to seize his alleged runaway slave, Edward Tarr. Rather than rubber stamping the alleged sale and Montgomery’s request to seize Tarr, the magistrates thought it only fair to give Edward a fair hearing. One-month later Tarr and Montgomery appeared before the magistrates and Tarr presented his case. Montgomery and Joseph Shute clearly underestimated the strength of Edward Tarr. He came into court as well prepared as any scholar could have been. He presented a copy of The Will of Thomas Shute, 1748, which stipulated the terms Tarr would have to meet should he wish to purchase his freedom. He produced a document signed by the executor of Shute’s will, attesting to the fact that Tarr had earned his freedom by paying 6 pounds each year for 6 years, a sum of 36 pounds. Montgomery was at a loss and knew it. He was given one month to respond to the evidence and told to appear in the December court to make his case. Tarr was instructed to remain in Augusta County pending the final hearing and had to post an unusually large, 500-pound bond as assurance. Montgomery was a no-show in December and Tarr maintained his freedom. Tarr insisted that the magistrates in this case, provide him with all records gathered by the magistrates, including their written decision, finding of facts and validation that Edward Tarr was indeed a free landholder. Tarr’s exceptional life functions as a lens, bringing into focus a time and place of shifting paradigms. McCleskey observes: “On the one hand you look at Tarr and he’s such an anomaly because he seems so gifted. He makes everything looks so easy. Tarr seems to come breezing in and nobody challenged him about the woman. Nobody minds it’s an interracial marriage. It’s not just because he’s valuable as a blacksmith. A number of records point to him being a very pious man. His spiritual quality really connected with the kind of practice that the Presbyterians in this region west of the Blue Ridge were having in that day, so partly his faith made it easier for him to integrate.” Born near Convoy House, County Donegal in Ireland, Catherine appears to have been a sister of James Montgomery (1690-1756) and therefore, my father’s 5x great aunt. Following the death of her first husband, Alexander Stewart, Catherine remarried in 1713, in Donegal, to James Patrick Calhoun, the son of Reverend Alexander Calhoun and Lady Judith Hamilton. Patrick and Catherine took their children to America in 1733, after her Stewart children had grown. They soon settled into the Chestnut Level neighborhood of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Around 1748, sometime after the death of her husband, James Patrick Calhoun, Catherine moved her family to one of the lots in Borden’s Patent in Augusta County, Virginia. One can assume she was drawn by the presence of her brother, James Montgomery, and the cluster of Lancaster PA, Celtic transplants. Deeds indicate that she and her adult sons acquired patents for lands on Reed Creek. Those deeds are as follows: March 1748: 335 acres on Reed Creek to William Calhoun March 1749: 159 acres on Reed Creek to Patrick Calhoun April 1749: 610 acres on Reed Creek to James Calhoun March 1651: 594 acres to James Calhoun, on Reed Creek on a place called ‘The Cove.’ April 1654: 64 acres on Hay Creek headwaters to James Calhoun The Calhoun men were deeply involved in county safety and maintenance. Records indicate that they were responsible for road construction and maintenance as well as maintaining and commanding a militia to stand guard and protect the settlers. Road construction was vital, as anyone who has played Catan can testify. The game is based on the actual strategies of men like the Montgomerys and Calhouns. Roads offered a path for transporting migrant families, commodities to market and a passageway to palisade forts in perilous times. In November of 1746, George, Ezekiel, William and Patrick Calhoun were appointed workers on a road from Reed Creek to Eagle Bottom. The road was destined to go over top of the ridge that separated the drainage basin of the New River and that of the south fork of the Roanoke River. James Calhoun was appointed overseer of the effort. Augusta County court documents reveal an ongoing dispute between the four Calhoun adult sons (James, Ezekiel, William and Patrick) and James Patton. On September 19, 1746, James Patton filed a charge against the four complaining that four had defamed his character. He identified them as “divulgers of false news to the great detriment of the inhabitants of the colony and it was ordered that they be committed for the November Court.” Patton’s case against the four lingered in the court system and a hung jury did not resolve the situation. Again in 1750 Patton returned to court charging the four with slander. This time the reason is in evidence. The Calhouns had been spreading the word that Patton, “had made over all of his estate to his children to defraud his creditors and that he had no title to the lands he offered for sale on Roanoke and New rivers.” The case was thrown out of court in 1754. It was in 1754 that Native uprisings along the Blue Ridge became more frequent and brutal. At the height of the French Indian War the population in Augusta County was on pins and needles. James Montgomery took his family out of harm’s way during a first wave of attacks but mustered his regiment for battle when a second wave of attacks occurred. With the death of her brother, James Montgomery, at the hands of hostile Natives, Catherine Montgomery Calhoun and her family of children and grandchildren, moved south to Abbeville, Granville CO, South Carolina. Catherine moved her family in the middle of winter and arrived in Granville in February of 1756. Catherine’s sister-in-law, Anne Montgomery, and the Edward Tarr family had moved north to Lancaster PA for reasons of safety at the same time. Catherine’s homestead was located where Calhoun Creek enters the Little River. A plethora of deeds can be found in South Carolina archives and those deeds reveal the century old close connections of families, dating back to Scotland and Ireland. Among the caravan moving in from Augusta County we have Alexanders, Andersons, Pattons, Stewarts and McClelands. The name Anderson caught my eye, as Hugh Montgomery, a great grandfather in our tree, married Caroline Anderson. Two Anderson men, Daniel and John, acquiring land in Granville County in 1759 are nephews of Caroline. Deeds issued to the Calhoun men identify acquisitions in the years 1758 and 1759. Properties range in size from 100 acres to 400 acres in Granville County and specifically Long Cane Creek of Granville County, SC. The possessions add up to 1550 acres and are distributed among four men, including a new name, Hugh, among the faces. One might assume Hugh is a young adult son of the one of the 5 Calhoun sons of Catherine. The families were settling onto land that was sixteen miles from the nearest Native settlement. They assumed they were a safe distance from any trouble. However, there was one minor problem associated with the Long Cane settlement. The Cherokee had only recently helped the British defeat the French and the British government had been kind enough to assure the Cherokee that this land was their land as compensation for the alliance that made friends of the two nations: Cherokee and England. This was the same issue, during the same time period that was driving a wedge between Cherokee and pioneers in Watauga in the Smokey Mountains. On the morning of January 31, 1760, a messenger came through the settlement and reported that hostile Cherokee were moving toward the village. Within two days the villagers, including Catherine, prepared to evacuate. They loaded wagons and provisions and on February 1, more than 200 settlers of all shapes and sizes and age, moved out for Augusta, Georgia, a larger town about 40 miles to the southeast. Only ten miles into their journey several wagons became hopelessly stuck in the mud of Long Canes Creek. By the time they had all the wagons across the creek it was dark, and they chose to camp for the night. When darkness settled in, they were attacked by a band of Cherokee. Some of the settlers escaped by horseback, some by foot, many found a place to hide among the trees of the forest. Twenty-three settlers, mostly women and children, were left dead at the sign of the massacre. Per one story, “The Indians had torched all the wagons and nearly all the goods were stolen.” Per another story, the forest was torched but the wagons and goods were not touched. Who knows? It depended on what news source people followed. Some things never change. Catherine Stewart Calhoun nee Montgomery, her son James and his wife were among the victims. Also found lying in the forest dead was a young granddaughter, Kitty Calhoun, William Calhoun’s daughter. Two Calhoun girls, ages 3 and 5, granddaughters of Catherine were abducted by the Cherokee. One, Anne, eventually returned, but the other was never heard from again. William Calhoun never recovered from the loss of his daughter and family history reports that he separated himself from his siblings and moved closer to the Atlantic coast and the safety he might find there. He was no longer interested in life on the frontier, fraught with so much risk, violence and bloodshed. Catherine Montgomery was 76 years old at the time of her death. A monument was erected in the 1790’s by Catherine’s son, Patrick Calhoun. Patrick was the father of the Senator of South Carolina and Vice President of the United States, John C. Calhoun. The following news articles in the South-Carolina Gazette soon told the story: “Yesterday night the whole of the Long-Cane Settlers, to the number of 150 souls, moved off with most of their effects in Waggons; to go towards Augusta in Georgia, and in a few hours after their setting off, were surprized and attacked by about 100 Cherkees on horseback, while they were getting their waggons out of a boggy place. They had amongst them 40 gunmen, who might have made a very good defence, but unfortunately their guns were in the waggons; the few that recovered theirs, fought the Indians half an hour, and were at last obliged to fly. In the action they lost 7 waggons, and 40 of their people killed or taken (including women and children) the rest got safe to Augusta.” Settlers on the frontier had an early warning and defense system that included messengers on horseback. The newspaper reported that: “An express arrived here with the same account on Tuesday morning and informs us he had since been at the place where the action happened, to bury the dead, and found only 20 of their bodies, most inhumanly butchered; that the Indians had burnt the woods all around but had left the waggons and carts there empty and unhurt. The Indian who killed Captain Tobler, left a hatchet sticking in his neck, on which were 3 old notches, and 3 newly cut.” So, ended the life of the matriarch of the Calhoun family. Hissy Fits Among the Family Historians A second story always unfolds when digging through the layers of research laid down by previous generations of family historians. This second story runs as a thread through the collection of articles and letters gathered by descendants related to Catherine Stewart Calhoun nee Montgomery. In recent centuries, prior to the internet, before telephones and all the electronic gadgets that infest our world today, folks depended on the printed word. The hard copy was the only copy available, other than oral history. Families organized their pursuit of ancestors in an organized fashion, often in societies such as the Montgomery Clan and Allied Families. They posted their findings in gazettes and journals. Local colleges would often print essays or research revealing family histories in a manner that resembled scientific findings. A rift occurs among Montgomery historians and it is the kind of issue that reflects on one’s attitude toward British royalty and religious affiliation. During the English Civil War, one was either pro Parliamentarian (Cromwell/Puritans) or Pro Royal (King Charles I/Anglican). In 1688, during the Glorious Revolution, one either supported King James II of Scot/Catholic lineage or one supported his daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange (Dutch/Protestant). The thought that Catherine Stewart Calhoun nee Montgomery, the matriarch of a Calhoun family renown for separation from all things British, could be connected in any remote way to the Stewart royal lineage of Scotland and England, was at the very least sickening to many of the Montgomery clan. This, even though three of their direct ancestors, the Viscounts of Great Ards, had dedicated their lives to the military endeavors of the British monarch. The very suggestion in any publicly printed article that a Calhoun woman could have been found in bed with a Stewart was met with the gnashing of teeth. Within a clan or family there has always been a senior citizen who knew the historical details and had an accurate recollection of the ‘family facts’ if you want to call them that. One such person was Mr. Orval O. Calhoun, of Cobourg, Ontario, Canada, a Calhoun descendent and one who is universally acknowledged as being the authority on Calhoun research. He reported that the Catherine Montgomery and Alexander Stewart’s marriage did exist. A century ago, a novice family historian, Mr. Tracy Forsythe, seeking the truth went right to the Zen Master, the chief arborist of family trees himself and contacted Mr. Orval Calhoun. Orval’s response to Mr. Forsythe’s’ query was reported as such: “Yes, I know of Alexander Stuart (later changed to Stewart) coming to Ireland about 1700 and marrying Catherine Montgomery about 1704/1705 when she was 20 years of age, but she was NOT a widow Calhoun, as listed in some records by mistake. Yes, I’ll agree, the Calhoun family sure kept the secret of Catherine Montgomery’s marriage to Alexander Stuart. I do believe the Stuart version of the affair, why deny it, when it is in the Records; I daresay the item is in the Stuart or Stewart papers in the PRO in Belfast, Ireland, that is where the Stewart papers are and could be researched by anyone. She was a Widow Stewart when she married Patrick Calhoun. Then, when Patrick died, she became a Widow Calhoun.” The Stewart Clan Magazine, published by George T. Edson, found the evidence supporting Orval’s pronouncement that Catherine Montgomery did indeed marry Alexander Stewart. They published the findings in April of 1939. An author in a separate journal then cautioned readers, “We may never know for sure which recordings are correct and which are theory, unless they are researched with an open mind and no stones left unturned.” It is clear by this last comment that George T. Edson, was praying that God would intervene and allow the Calhouns to make peace with the idea that one of their iconic heroes, Catherine Montgomery Calhoun had previously shared her bed with a Stewart. The generation of kids that grew up in the American colonies with Samuel Montgomery gave us the American Revolution. The Simpsons, Wheelers, Taylors, Waddys, Davis, Kincheloes, Andersons, Cooks, Pullins and Ushers can all point to sons and daughters whose lives were tangled up in the war that cut America loose from the control of England. Among these families we find the pioneers of the Over Mountain territories and the less fortunate sons in those British family wills that gave estates to the oldest son and left the remainder of the children to wander the earth in search of new wealth and a rich marriage. Some of this generation of the family tree were major landholders in Virginia in the century prior to the Revolution. Many of these families also represented the migration of the Scot Irish from the Atlantic port cities into the Shenandoah Valley and then either down into the Carolinas, or ‘over the top’ of the Appalachians and into the Ohio Valley countryside. Their migration was not without conflict. Those who came over the Blue Ridge in Virginia or down through the valleys from Pennsylvania in the 17th and 18th Century were always in conflict with the Native nations. Powhatan understood what was at stake for his people when the European settlers first encroached on his lands along the James River in 1610. The writing was on the wall for the Powhatans of the world and it was a Banksy styled message, a call for activism that required an Old Testament response: an eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth. Many among the surnames of Samuel’s generation in our family tree were yeoman landholders in Virginia in the century prior to the Revolution: Simpson, Wheeler, Taylor, Waddy, Tate, Kincheloe, Anderson, Cook, Pullin, Usher and Montgomery. They were Over Mountain pioneers whose lives became tangled up in the American Revolution. They began life as the less fortunate younger children in British wills that provided for the oldest son and left the rest with a lesser share. These families often represent the migration of the Scot Irish from the Atlantic port cities into the Shenandoah Valley and then either south into the Carolinas, or ‘over the top’ of the Appalachians and west into the Ohio River Valley. Samuel Montgomery was one of seven sons of Hugh Montgomery (1710-1785) and Caroline Anderson (1710-1767). Hugh and Caroline nearly produced a football team with ten children. Seven boys and three girls (that we know of) were born in the span of seventeen years, a feat which kept Caroline in competition for the Breeders Association honor of Mother of the Year. Samuel married Mary Polly McFarland in Virginia and moved to within eight miles of Perryville, Kentucky. Historians are unable to pinpoint the year of that move but have concluded that Sam and Polly arrived in Kentucky no later than 1794, as their son Samuel Jr was born in Kentucky in that year. Samuel Senior’s brother John (b 1741) had explored all of Kentucky as early as 1774 as a member of the Long Hunters of General Knox. John Montgomery’s name appears on the rolls of the General’s garrison at Harrodsburg and he is identified as a member of the party that scouted the Dick’s River Valley in present day Green County. John Montgomery is identified in Collins History of Kentucky as having come into Kentucky to settle in 1779. He arrived, by way of the Ohio River, with his wife and children and a fellow Virginian, James Davis. Together they established the settlement that became Hopkinsville, Kentucky. In 1811 Samuel and Polly Montgomery rolled their wagon and all the stuff they had acquired in life across the Ohio River and into Gibson County, Indiana. They settled on the Northeast quarter of section 24, town 3, range 12 west in what had previously been called Knox County. The land had been held by Samuel’s nephew, Walter Montgomery, who had arrived in 1806. Samuel died in 1815 and was buried on this farm. Reverend Levin Wilson of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church authored a book titled simply, Rev. Levin Wilson’s History. In it he described Samuel Montgomery as “a quiet, peaceable, industrious and religious man, and highly esteemed by all his neighbors. He was an elder in the old Presbyterian Church in Kentucky, and in the fall of 1814 three years after coming to Indiana …. consented to organizing the Cumberland Presbyterian Church.” Matilda’s father, James Montgomery, born in Kentucky in 1783, was the fifth son of Samuel Montgomery (1743-1815) and Mary Polly McFarland (1753-1819). D.B. Montgomery described James as “a wealthy man of his day. He owned and raised his family on the north-west quarter of section 24, town 3, range 12 west. He owned a negro, called Pete, who had almost full control of his affairs and contributed largely to his success in life. He (James) retained more Irish characteristics than any other members of his family, as he talked in a very brusque Irish brogue.” James “owned a negro, called Pete….” The year was roughly 1800 and James was living in what would become, in 1816, southern Indiana. We think of Indiana as a ‘free state.’ What’s the deal? In 1787 Congress organized the Northwest Territory (Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin and NE Minnesota) under the Northwest Ordinance. The Ordinance prohibited slavery by stating “that there shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory.” It would later be decided that anyone who purchased a slave outside of the territory could enter and reside there with their slaves. This action typifies our nation’s wrestling match with the issue of slavery. The founding fathers found it necessary to placate slave owners. Slaves at the time included Natives who had been captured and bound into slavery by French settlers in the previous centuries. There were several reasons why our nation’s leaders allowed settlers to bring slaves into the Northwest Territory. Chief among those reasons was the need to encourage settlement of the territory. Native tribes were still prevalent in the region and at war with pioneers. The colony of Virginia had provided the bulk of settlers in the county of Kentucky and those settlers provided the soldiers needed to keep Native attacks in check. A prohibition of slavery in the Northwest Territory would have severely reduced the migration of people needed to successfully colonize the territory. So basically, the founding fathers posted billboards in Ohio River port cities reading, “Yo! Brothers of Virginia! The NW Territory welcomes you! Bring your slaves!” The Ordinance stated that the Virginians “shall have their possessions and titles confirmed to them and be protected in the enjoyment of their rights and liberties.” Many decided to keep slaves. Apparently, James Montgomery kept Pete in his custody when he crossed the Ohio from Kentucky. Abolitionist would gain control of the Indiana state legislature when it became a state. They outlawed slavery in the 1816 Constitution. The last slave was freed in 1820. James Montgomery built a horse driven grist mill in 1811 in Gibson County, Indiana. He was the overseer of the poor in 1814 and a commissioner supervising the accounts of the poor in the latter half of that decade. George Rudolphus Smith moved into Posey County, established his distillery and grist mill. One ‘state’ to the west, Hezekiah Stilley and Sarah Davis were hunkered down in Makanda, Illinois in 1803. Illinois would become a state in 1818. The Anderson Branch of the Montgomery Tree We have traced the lineage of Matilda Montgomery back through several generations to William Montgomery on this side of the ocean. Now it is time to introduce the wife of Hugh Montgomery, known in her own right as Caroline Anderson (1709-1767). Concerning the position of Cecelia Massey in our Smith family tree: Frankly, I could give a rat’s ass as to where she belongs. Not to be crude about this, but honestly, the woman deserves to rest in peace. Put her somewhere in the tree and move on. Several variations of the Anderson tree show Ms. Massey married to one of three men in the lineage: either the father, the son or grandfather. I understand the consternation this causes and the apoplexy this creates among decent human beings. One does not wish to think that one woman could marry three generations of men in one family. I am not interested in Cecelia Massey. I don’t have a dog in that family fight. In Pedigree Chart 21, I show Cecelia as the wife of Robert Anderson (b 1640) and for doing so, I may expect retribution and banishment from all Anderson family events, including clambakes, over the course of the next century. I am more interested in finding the father of Robert Anderson (b 1640) and this interest draws me right into center ring of Bout #2 in the Anderson Family Fight and several interesting encounters with The Gatekeeper.The tenor of The Gatekeeper’s voice is evident in this message: “Richard Anderson is by rumor and ‘family tradition’ alleged to be the ancestor of the Anderson families of the York River. How much of this is family tradition passed down and how much was made up by early researchers looking at ship lists I can’t be certain by examining the published literature. I have not seen a presentation of strong evidence of this association in the sources I have seen.” That is about as transparent and firm a footnote as I have found in the annals of family history. I sympathize with The Gatekeeper. One person’s hypothesis easily becomes a fact for historians. A story that began as a guess at a dinner party in previous decades soon becomes part of history. By such efforts, speculation is made legendary. In one short paragraph The Gatekeeper provides five warning signs regarding the citing of Richard Anderson as progenitor in the Anderson tree. Terms like ‘by rumor,’ ‘alleged,’ ‘made up,’ ‘can’t be certain,’ and ’have not seen’ all make it very clear: The Gatekeeper is uncertain about a descent from a Richard Anderson. Elizabeth Hawkins was the niece, not the daughter of Admiral John Hawkins in the Smith family tree. He is the guy who played a major role in taking down the Spanish Armada. The Admiral’s status as Elizabeth’s uncle, makes him my father’s 10th great uncle and my son’s 12th great uncle. But, Admiral Hawkins is also found in my wife’s Whittington family tree as her 11th great grandfather, that would make him my son’s 12th great grandfather. Go figure. My son’s 12th great uncle is also his 12th great grandfather. One look at the resume of Admiral John Hawkins begs the question: Who wouldn’t want bragging rights to this heroic icon? This guy built the formidable British navy, destroyed the Spanish Armada and stole tons of gold ducats from the Spanish who had previously stolen the gold from Native Americans. Born in Plymouth, England in 1532, Hawkins was the son of William, a very wealthy sea captain in Cornwall. Growing up in such a seafaring family, young John was well acquainted with all that it took to survive and gain wealth as a sea merchant. Unfortunately, he was also the worst of the pirates and a savage, brutal, plug ugly slave trader, which makes him a bad pick for any family ancestry fantasy team. In 1562 Hawkins sailed to Africa, where he captured 300 people to sell as slaves. He transported this human chattel to Santo Domingo, in the West Indies, and traded them for pearls, hides, ginger, and sugar. Although the colonists in Spanish territories had been forbidden by Spain to trade with any other nation, they were eager to buy slaves from anyone transporting human cargo. John Hawkins’ second voyage two years later was equally profitable. Luck ran out for Hawkins on his third voyage. Accompanied by his cousin Sir Francis Drake, Hawkins and their six ships were trapped in the harbor of Veracruz. An armed Spanish fleet attacked. Of 6 ships, only the vessels commanded by Hawkins and Drake were able to escape. For 20 years Hawkins remained at home in the service of Queen Elizabeth I. As treasurer and controller of the navy, he built up Britain’s fleet, preparing to challenge Spain over supremacy of the seas. He armed the vessels more heavily and redesigned them to make them faster. He also introduced modifications in ships and sails that were battle tested in practical experience at sea. In the great battle in which the Spanish Armada was defeated in 1588, Hawkins served as a vice admiral. He was knighted for gallantry. In 1595 Hawkins sailed with Drake on what was to be the last voyage for both. John Hawkins joined the expedition hoping to rescue his only son, Richard, who was held captive by the Spanish in Lima, Peru. Admiral Hawkins died at sea on Nov. 12, 1595, near Puerto Rico. Dysentery got the better of both he and Francis Drake. In his will he identified his second wife Margaret and his son Richard. That was it for his immediate living family. He wasn’t sure his executors would be able to locate Richard and indicated that if they couldn’t find him after three years, those properties and wealth set aside for Richard should get reassigned per John’s instruction. Lacking any other children, Admiral Hawkins was generous in distributing his fortune to nieces, nephews and friends. Richard Hawkins was found eventually residing, briefly, near the Peter Smiths of Yeocomico in Westmoreland County VA. But, Richard was found too late to benefit from his father’s Last Will. True story. Elizabeth Hawkins (1584-1635) and Richard Anderson (1585-c.1635) One niece who benefitted from the will of John Hawkins, was our Elizabeth Hawkins Anderson. She was born on March 21, 1584, in All Hollows, Honey Lane, London, England. You have to love that sweet address, and isn’t it incredible that we can find these various records at all, so many centuries after the fact? Elizabeth was the daughter of the Admiral’s brother William Amydas Hawkins and Mary Halse. Amydas was her mother’s maiden name. Our Elizabeth married Richard Anderson, born 1585 in Pendley, Hertfordshire, England, and died in Williamsburg VA. Again, Elizabeth was not the daughter of the Admiral Hawkins as claimed by some authors in the Anderson family tree, but his niece. I met with the Gatekeeper in a clandestine manner on the internet. I passed myself off as a retired educator, dressed in pajamas and carrying a mug of freshly drawn cappuccino. The Gatekeeper was apologetic regarding the false claims made by several of our peers claiming John Hawkins as a direct ancestor. “I do not personally show him as a great grandfather of any kind,” the Gatekeeper started. “I cautioned all who read my blog to research such claims thoroughly. That’s all I can do, you know. You know? Right?” A few more niceties and I then shut down the messaging to avoid a Tinder styled romance on Ancestry.com. I left the chat room at that point and fidgeted with my Rubik’s Cube. The name of the Anderson immigrant ancestor, Richard Anderson, appears on Hotten’s passenger list for a ship Merchant’s Hope (owned by William Barker) in 1635. Richard’s age was listed as 50. There is scant evidence providing any glimpse of his life in Virginia. Some believe he sent his sons to Virginia several years prior to his own arrival. This was a common enough practice when an investor had adult male children who could act as an advance man in a family business whether it be mercantile, agricultural or land development. There is evidence that our Richard Anderson was preceded by several immigrant men of the same name. Two men named Richard Anderson arrived, one in 1632 and the second in 1635. But, which of the men was the son of Richard and Elizabeth Hawkins Anderson? Was it Richard, age 17 in 1632 or Richard, age 30 in 1634? And what is the point of dwelling on it? Richard and Elizabeth Hawkins Anderson had several children: (1) Thomas, (2) the Reverend Richard Anderson II (b 1615, in London) and (3) John (b 1614, in London). All three men lived as adults and died in Gloucester, Virginia. The Anderson historians are torn as to which of the three sons qualifies as my father’s 7x great grandfather. The answer is anyone’s best guess. One of the three men was the father of our Robert Anderson (b 1640). An examination of what little history is available might provide an answer. The answer to the question wasn’t half as interesting as the online encounters that provided a lineage. I asked the ‘The Gatekeeper’ for a lead that might lead somewhere. That is why ‘a lead’ is called ‘a lead,’ after all. Several months later I received a cryptic message that advised simply: “Can’t respond now, too busy.” I was on my own. The First Son of Richard and Elizabeth Hawkins Anderson: Thomas Thomas was born, but when? No one can peg a date. At some point in time, between 1615 and 1620, he was born. He arrived in Virginia, but when? No one can be sure. He lived in Gloucester VA and worked on ships. He married, but the name of his wife is unknown. He had children. But when people start linking children to parents, they take every Anderson born in Virginia and throw the kids into any, and all, of the three son’s families, and so it goes. This journey in life of Thomas Anderson is littered with question marks. Several Anderson trees show one of the sons with 32 children. I only know of two men in our family history who had 32 children, King John I ‘Lackland’ Plantagenet of England and an Appalachian moonshiner who had little need for social graces and marriage contract. The moonshiner is on my wife’s side of the family. He appears to be unrelated to our beloved Wilbur Rancidbatch. The Second Son of Rich and Liz: Reverend Richard Anderson (1615- ) Is the Reverend our missing 7th great grandfather? Richard Anderson II embarked for Virginia aboard the ship Bonaventure in July 1632. The ships manifest tells us he was 17, therefore he was born circa 1615. Two years later a Richard Anderson, age 30, embarked for Virginia in the Truelove de London. Folks have concluded the younger of the two is our Reverend Richard Anderson, 7th Great Grandfather to my father. The Gatekeeper argues there is no evidence to substantiate the point. Even the noted Nineteenth Century historian, James Hotten, identified this Reverend Richard as the father of our Robert Anderson. The Gatekeeper cautions against accepting this designation and threatens action against anyone in the family who seeks to promote such a placement of Richard in the family tree. “Show me your evidence!” becomes a frequently occurring mantra blurted out, often in CAPS, in online exchanges. On July 25, 1646 “Richard Anderson, Clerk,” is mentioned in York County records. The term ‘Clerk’ identifies Richard as a minister of the church in colonial Virginia. On August 8, 1647, he witnessed the will of Nicholas Dale. Using Nicholas Dale as a reference point I can pinpoint the Anderson neighborhood. In 1647 the York River cut through the heart of York County. The north and south banks of the river were growing in population. Nicholas Dale settled to the north of the York River in 1638 with his wife Ann. They developed property near Allen’s Creek. It is assumed the Reverend Richard Anderson’s residence was also on the north bank of the York at Gloucester Point across the river from the city of Yorktown VA. Richard’s brothers John and Thomas also settled in this area. In 1651 the lands on the north side of the York River were removed from York County and Gloucester County was created. Richard and his wife eventually died in Gloucester County, as did his brothers John and Thomas. In 1657 Mr. Richard Anderson was listed in the estate settlement of Henry Lee. The ‘Mr’ preceding his name indicates he, Richard, was (still) a minister. The Lee name has become familiar in our family tree. We found Peter Smith and his descendants sharing the neighborhood with the Lee family in both Westmoreland and Prince William Counties. Henry Lee had arrived in York County in 1649. Peeter Smith soon appeared in Virginia, buying property in Doeg’s Neck. The Lee family bought land adjacent to Peter of Westmoreland’s Bull Run properties in 1712. We looked at that plat map earlier. It is believed by many that the Reverend Richard Anderson’s wife was named Mary Spencer and that they were the parents of Robert (1640-1712) from whom, it is argued, we descend. But one significant family historian was not convinced that the Reverend Richard was the missing great grandfather in our tree. The Gatekeeper’s blog was inconclusive but redressed people with a hint of sarcasm and scorn directed at those who were quick to accept the Reverend’s credentials. There were very long pauses in my running Instant Messaging conversation with The Gatekeeper. There was nothing instant about the conversation. Days can lapse into weeks before one hears back from a genealogist who is communicating in text of any kind. I once read of a senior citizen who was eager to locate a great-great grandfather, Wallingford Eyesocket III. The matron posted a query in 1998 and waited 15 years for a response, only to learn that the Eyesocket she was looking for died intestate, childless and barren of children. She could not have possibly descended from Wallingford. He was the last of the Eyesockets. She was looking up a blind alley. While a gender was never revealed I had a gnawing feeling that The Gatekeeper was a woman, a soccer mom who was busy shuffling her children off to school and church related events. I suspected she was too busy to focus any energy on my begging and groveling in the dirt for a shred of evidence that would help me put a wrap on this Anderson branch of my family tree. Why was she adamant that the Reverend Richard was not my father’s 7th Great Grandfather? Why would The Gatekeeper dispute the great historian of the 19thCentury, James Hotten? If Hotten designated the Reverend as the missing link in our tree, why not pencil him in? The Gatekeeper was one of those family historians who is always critical of everyone else’s efforts but never able to offer the slightest suggestion as to how to proceed. When the brick wall stands clearly and solidly in front the legion of amateur family history buffs, the gatekeepers of the world sit smugly by, making snarky comments as the residue of bonbons dribbles off the chin. Wannabe genealogists, armed to the teeth with pencils, pens, index cards, software systems, maple bacon fritters, coffee, Scotch or something stronger, will dig in and share their findings with other sincere family historians. The Gatekeepers are the Mitch McConnells of the world, stopping everyone in their tracks, saying no to anyone who appears to be a newbie in the family tree. It is a bit like watching a Spanish Inquisition hazing practice in a demonic frat house. The current generation of family historians are passionate disciples of Professor Lewis Gates and graduates of his televised program Finding Your Roots. They are each desperately seeking guidance as they wade through a vast collection of documents and history. The Gatekeepers of the world intend to limit access to their fine breeding, their aristocratic heritage, their Revolutionary War soldiers and daughters of that revolution. What value does a DAR (Daughter of the American Revolution) certificate have if every peasant in the county discovers he or she is also descended from the upstart punk rockers who marauded across the countryside with General Washington, looking to make target practice out of a Redcoat? What was The Gatekeeper hiding, protecting or seeking? The erratic behavior was inexplicable. And then one day a shard of information fell into my lap. The Gatekeeper dropped a John on me. No, I didn’t say that quite right. Not a john like a toilet, although I did feel a bit crapped on over the months of trying to deal with this source. Details regarding the third son, John Anderson were dangled in front of me as a possible lead. Could this John, the third son of the Andersons, be my father’s 7x great grandfather Robert (b 1640)? And who gives a rat’s ass? Really? I kept coming back to that one question and I don’t know why it must be a ‘rat’s ass’ anyway. Why a ‘rat’? Their asses are tiny. Who came up with that in the first place? Why not an elephant’s ass? They are huge. Or a baboon’s ass, they are obvious and ugly. I digress. The Third Son of Robert and Elizabeth Hawkins Anderson: John Anderson (1615- ) Beginning with the few chards of evidence provided I researched further into the history of John Anderson. He arrived on the Merchant Bonaventure, having embarked in the winter of 1635. His age was listed as 20. He took up residency at Gloucester Point on the North Bank of the York River across from the city of Yorktown VA. He was a shipwright by trade and was joined by his brother Thomas in the shipbuilding business. Four hundred years later, the same harbor is bustling with sea related activities, merchant ships, naval vessels, ship building and repair work. The Anderson men provided an invaluable service to the King’s efforts to colonize Virginia and tap into the lumber resources available. The Brits were competing with the Spanish and Dutch for control of ocean travel and New World resources. As the Brits expanded their naval war capacity and merchant marine activity they were denuding their home country, creating boards for ships and fuel for their furnaces. According to family tradition the Anderson family filled a great void in the English economy. They capitalized tremendously on the King’s and Admiral John Hawkins’ efforts to create a great British navy. They began building ships in the new world, clear cutting the North American forests and creating a great fortune for themselves. It was the beginning of a great capitalist tradition: Destroy resources. Create wealth. And then it happened. With little fanfare and no press conference whatsoever, the Gatekeeper announced that Robert Anderson (b 1640) was anointed the son of John Anderson. No explanation was given. No evidence provided. I surmised that The Gatekeeper had Brick Wall Fatigue (BWF). Exasperated by years of frustrating research and decades of shredding everyone else’s work, the Gatekeeper had gone into a Deep State and had given up. While The Gatekeeper eliminated the other brothers (Thomas and Richard) as direct ancestors in Virginia, I was reluctant to blindly follow the Gatekeeper’s analysis. I was going to power through and find the father, come Hell or high water. I wrestled with the same small shreds of evidence. I pummeled the profiles of distant ancestors and left some of them crumpled in the back alleys of Yorktown. I found nothing new. I too was stuck, mired in the mud of the York River backwaters. I consumed large quantities of coffee, binged on maple bacon fritters and padded about the house in slippers that are cloth replicas of Bart Simpson. I awoke one morning at precisely 3:16. The tamsulosin had worn off and I immediately headed to the bathroom, the john. Those men older than 62 will completely understand the urge. When you gotta pee, you gotta pee. For a brief lucid moment, as I hovered over the toilet on shaky, arthritic legs, I realized I was looking at the answer: thee John. I returned to my desk, grabbed a pen and a piece of scrap paper and scribbled the words, ‘John 3:16’. It was too Biblical to ignore. I returned to my bed and fell into a blissful sleep. I had found the 7x great grandfather. My search in this case was complete. John Anderson had to be the carrier of the Anderson family DNA that contributed to my existence. He had to be the father of Robert (b 1640). As much as it pained me, I agreed with The Gatekeeper. It was after all, ordained by God over a toilet bowl in the Northwoods of Wisconsin. And that my son, is how these family tree decisions are sometimes made. Robert Anderson (1640- ) Regardless of who his father had been, Robert Anderson (b 1640) became the first Anderson born in Virginia. He and his descendants took 700 acres of land on the south branch of Pamunkey River and turned it into the 5,000-acre Goldmine Plantation. When I came across the reference to the Goldmine Plantation I was, at first, dumbstruck. Was ‘The Gatekeepe’ protecting some vested interest in a family treasure that had descended via false claims, forged documents and phony wills to a Trust of The Gatekeeper? Gold mine? I had never heard of a gold mine that had produced any sizable amount of ore on the east coast. There is plenty of evidence that the British panned for gold in North America. They dug for gold. They groveled in the dirt for gold. They desperately wanted to find the same fortune in gold in North America that the Spanish and Portuguese were stealing from the people of South and Central America. When British efforts to find gold failed to pan out, they did the next best thing. They stole gold from the Spanish and Portuguese. They sent guys like John Hawkins out to sea dressed like Jack Sparrow and they played Pirates of the Caribbean. These pirates, along with the legitimate merchants in the marketplace, all needed shipyards on the American coast. The Anderson men opened shop. The Goldmine they spoke of when naming their plantation was nothing more than a meaningless stream that crossed their estate. Or, metaphorically speaking, the real gold mine was the ship building business they created in their New World setting. Any hopes The Gatekeeper had of claiming a family fortune in an actual gold mine were shattered. The tremendous U.S. Naval Yards now found in Norfolk VA are the result of 17th Century efforts made by the Andersons. I would not have been surprised to learn that The Gatekeeper was trying to lay claim to the entire American naval fleet. I sent a cryptic note to the Gatekeeper offering a small amount of condolence: “Hey! Sorry you were unable to turn all of your research into a lawsuit and a stake in the family fortune, aka the Goldmine. Better luck next time.” I got a quick response, “Thanks. No worries. I found a great uncle who built an empire based on pork bellies.” Robert Anderson (b 1640) had a wife…. Now this is where I must watch myself very closely. I know that The Gatekeeper will be following my every move online. I may pay dearly if I am not careful. I value my kneecaps, but I could lose them if I error in reporting any further Anderson data. Many people in the Anderson family tree believe Robert (b 1640) married Cecelia Massey (1646-1712). Robert and Cecelia, in turn, had a son Robert II, who later earned the title ‘Captain.’ Now that I have mentioned the name Cecelia Massey, I must ask you to pray for my safety. The Andersons take this debate seriously. If you do not hear from me in two weeks, please come looking for me. I have every right to believe that I could be found wrapped in kelp and hanging by my ankles from the highest branches of the large Oak behind our home. Subscribers to the lineage just outlined are periodically shamed by The Gatekeeper for their reliance on Fake News and conducting shoddy research. I contend that given the option of choosing a great grandfather some people prefer preachers (Rev Richard) to ship magnates (Brother John). It is all a matter of taste and research be damned if nothing conclusive is found. How we get from Richard and Elizabeth Hawkins Anderson to our known great grandfather Robert Anderson (1640-1712) seems a matter of discretion. I made the decision in a most intelligent and thoughtful process imaginable. In the process I cast the Reverend aside and chose his brother John, the ship builder as my father’s 7th great grandfather in the Anderson branch of our tree. He makes for a better story. Captain Robert Anderson (1663-1716) and Mary Overton (1673-1735) Robert (b 1640) and Cecelia Massey had several children. Among them we found our Captain Robert Anderson, born in 1663 in the Pamunkey River juncture with the York River where the York empties into Chesapeake Bay. It is at this point in the Anderson family tree that all evidence points to the following lineage. Captain Robert Anderson (b 1663) married Mary Elizabeth Overton in 1690 in St Peters, New Kent, VA and that has been substantiated. St Peters church was also the church in which the James Tate family worshipped in the 1600s. You may remember the Tates from previous chapters. James Tate, my 7th great grandfather married Elizabeth Dandridge in this same small church. The Tates, Andersons and Overtons were well acquainted. Mary Overton was born June 28, 1673 in York River, York VA, and died 1735 in St Peters, New Kent, VA. She was a daughter of William Overton and Elizabeth Waters (of my wife’s family). Elizabeth was the daughter of Ann Waters, a widow who lived in St. Sepulchers, London. William Overton was born in England December 3, 1628 and emigrated to Virginia. Overton and Eben Jones had a 1681 headright patent for 4600 acres of land in New Kent County on the South side of Pamunkey River where it joins Falling Creek. They had transported ninety-two people. Among the headrights were William and Elizabeth Overton. 4600 acres was a sizable estate. Robert and Mary had between 12-15 children including our own Caroline Anderson. Robert Anderson, was identified as a headright of William Wyatt in 1685. This implies that Robert was coming into the colony circa 1685. When upper crust males come back into the colonies at the age of Robert, we assume they were handling family business, settling a will, or that they were sent by parents to England to gain an education and are now returning to the colony. Captain Robert acquired 1200 acres in New Kent County in 1690. Robert died in 1716 in Hanover VA. Caroline Anderson is identified as the wife of our Hugh Montgomery. That fact has been established as true by numerous authors over the centuries. We have met their son and my father’s 3x great grandfather in our tree, Samuel Montgomery. So that is it then, in a nutshell: the Anderson lineage in our tree. It has been three weeks since I published these notes online and nothing unusual has happened in my life. No threatening letters from The Gatekeeper, no harassing emails or instant messages. I am feeling somewhat safe. The pick-up truck with a gun mounted behind the driver in the cab has finally vanished from the entry to our driveway. I believe it is now safe to walk our dog down the road to the home of Wilbur Rancidbatch. The last I heard he was adding dandelion oils to a lager beer. Word that it has the flavor of STP3 Motor Oil has confused many of his neighbors but explains the fire that destroyed his shed. General Robert Anderson, Union Commander at Fort Sumter While our family history spins away from the vortex of the Anderson family there are some interesting cousins whose lives also descend from Robert and Mary Overton Anderson into the 19th and 20th Century. Take for example the Union Major General Robert Anderson (1805-1871) who had the unenviable duty of surrendering Fort Sumter to the Confederate forces in Charleston harbor. It was a rough day for the Kentucky born general who had graduated from West Point and believed strongly in the Confederate cause. Despite his southern leanings he remained a staunch Union soldier and committed to the oath he had taken to protect and defend the Constitution and federal government. When the Union forces returned to Charleston and seized control of the fort, they made sure that Robert Anderson was present to raise the flag of his country, the United States. The Major General firmly believed that the Civil War would have never started had he maintained control of Fort Sumter. He was the son Lt Colonel Richard Clough Anderson (1749-1826) and Sarah Marshall (1779-1854). Sarah Marshall descends from Peter Smith of Yeocomico by way of his daughter Martha Smith. Lt Col Richard Clough Anderson was a heroic officer in the Revolutionary War. He worked closely with Generals Washington, Monroe, Lafayette, Wayne and Pulaski. General Pulaski died in the arms of Lt Col Richard Anderson and gave him his sword to carry forward in battle. Anderson was friend and neighbor of Patrick Henry and entertained Henry, James Monroe, Andrew Jackson and other early American icons in his home. Lt Col Richard Clough Anderson was the son of Robert Anderson (1711-1792) and Elizabeth Clough and the grandson of our Robert Anderson (1663-) and Mary Overton. All the Andersons amd Cloughs in these several paragraphs relating to Civil and Revolutionary War figures are my father’s cousins. Do I say that to gloat and pretend it somehow makes me a better person? No, I say it to make the point: It’s a small world. And by the way, they are your cousins as well. Captain James Montgomery (1695-1756) and Anne Thomson

Robert Montgomery closed out his land transactions and his life in 1782. Robert and sons, James and William, gave power of attorney to John Montgomery and Walter Crockett to sell their properties on Reed Creek. They migrated over the mountains and into Kentucky County where Robert Montgomery died. He was an early settler in the annals of Kentucky history, following on the heels of family members like our own William Bailey Smith.Anne Montgomery and the Ex Slave, Edward Tarr

Catherine Montgomery (1684-1760) and the Long Canes Massacre

In fact, in my many readings I have noticed that Catherine’s marriage to Alexander Stewart is glossed over and well hidden in many, early Calhoun archives. Catherine’s progeny, her children and descendants, are only our cousins. Whether they be Stewarts or Calhouns is insignificant to me. There are no grandparents in the litter. It is the DNA Catherine was born with, as a Montgomery, that descended through generations and found its’ way into the marrow of Matilda Montgomery. However, I must advise that within that Stewart lineage we do find the likes of Robert the Bruce, King James I and II and Mary Queen of Scots who each occupy a perch in our family tree.Samuel Montgomery (1743-1815) and Mary Polly McFarland (1753-1819)

A separate book was published by an author who claimed the honorable Reverend was lying: “Samuel was never seen in the Cumberland Presbyterian Church.” Apparently, Levin Wilson did not know his own congregation or its’ founders. Obviously, someone had it in for Levin.James Montgomery (1783-1826) and Nancy Cook (1784-1850)

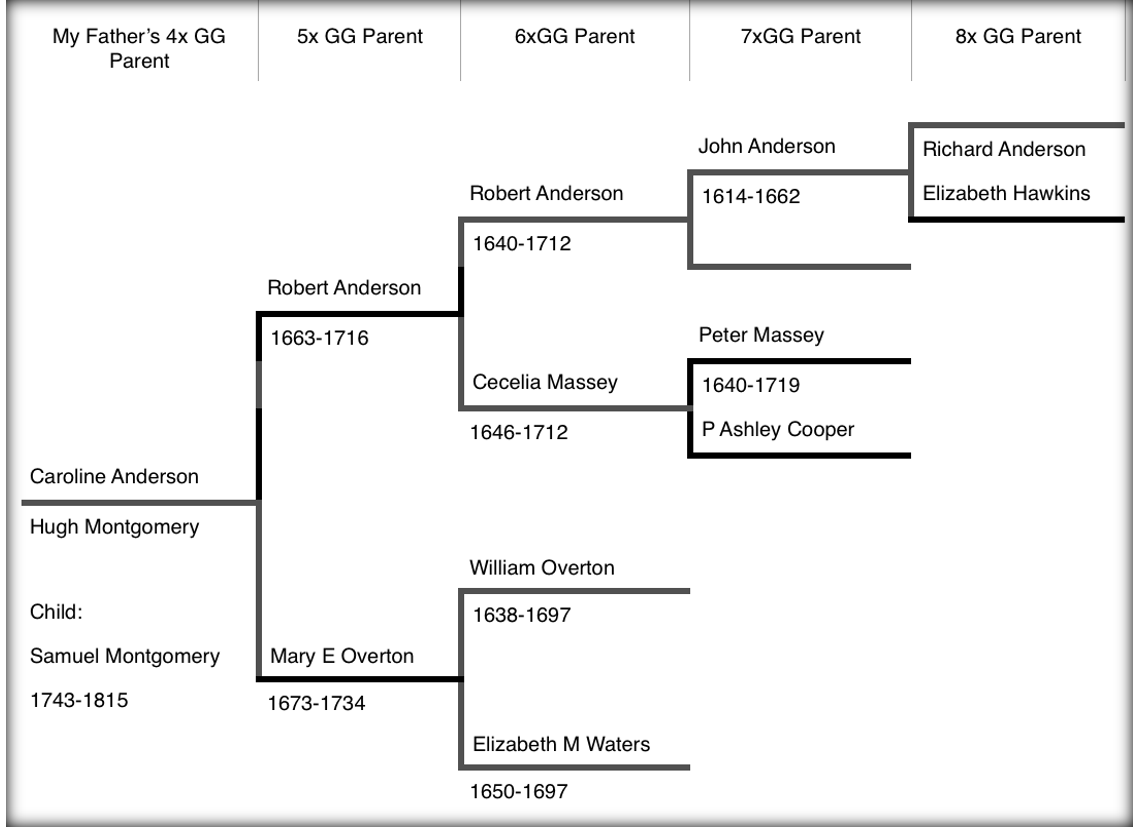

Pedigree Chart 20 pretends to show the descent of the Anderson family tree. I say, pretends, because the Anderson family archivists debate Cecelia Massey’s place in their family history. They are equally uncertain as to which of three brothers Caroline Anderson descended. The debate among the Andersons is all too typical and makes for a bizarre side show in this litany of ‘Who’s Who in the Smith Family Tree.’Pedigree Chart 20: The Anderson Branch of the Montgomery Tree

There is apparently one person who stands alone in the rank and file of Anderson card carrying family members. This person, known only as ‘The Gatekeeper,’ is thee Anderson family historian, and recognized as such by fledgling amateur genealogists who defer to The Gatekeeper in all matters of lineage and Anderson family history. The Gatekeeper exercises discretion and integrity in articulating the Anderson tree and I respect that sense of propriety.

There is apparently one person who stands alone in the rank and file of Anderson card carrying family members. This person, known only as ‘The Gatekeeper,’ is thee Anderson family historian, and recognized as such by fledgling amateur genealogists who defer to The Gatekeeper in all matters of lineage and Anderson family history. The Gatekeeper exercises discretion and integrity in articulating the Anderson tree and I respect that sense of propriety.

With little else from which to grow a family tree, Anderson historians ignore The Gatekeeper’s futile warnings and continue to claim Richard Anderson as the Emigrant Ancestor in their family trees. While little has been written about Richard Anderson, world history knows much about his wife Elizabeth Hawkins and her ancestors.Admiral John Hawkins (1532-1595)