The Davis family provided a wealth of information and constitutes one of the largest and deepest branches of our family tree. A second and even more prodigious allied family emerges from the annals of history when one uncovers the one-thousand-year-old story of the Montgomery family, the ancestors of Matilda Montgomery (and therefore the rest of us who descend from Leb Smith).

This family history predates William the Conqueror and the Norman invasion of 1066 and is found in British anthologies that track the lives of British aristocracy. Family history includes historical figures Alfred the Great, Rollo the Great and the Vikings of Scandinavia. This is one of two branches within our family tree that is proven to connect with British aristocracy. At one point in history the Montgomery clan had a legitimate claim to the throne but threw their weight behind a son of William the Conqueror. They were fierce defenders of the crown and some gave up their lives for the King. Long associated with the monarch and ruling class, the clan found itself on the losing side of The English Civil War in 1649. This accounts in part for their eventual journey to America.

Over the millennia Montgomery families within our clan lived in Normandy, England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland, (Great Britain). The patriarch of the family, Sir Roger de Montgomery, was the fifth most wealthy man in Great Britain in 1066. Roger was my father’s 24x great grandfather. Six hundred years later, the Montgomerys within our tree who migrated to Virginia did so because the family wealth disappeared, and the sons were determined to create a new life in a new land. While some family historians use the term ‘squander’ to describe the loss of the family estate, there were nefarious economic and military forces at work in England that eroded the accumulated wealth of this and several other prominent families and clans.

Drawing from several resources one can develop reasonable facsimiles of a family pedigree chart. With a bit of Sherlock Holmes detective work the descent of ancestors on both sides of the Atlantic unfolds. There are several places within the British family in which the original authors appear to have cobbled together the staircase on which the old ancestors descend into the present day. The British interest in maintaining such records began with the Domesday Book, a collection of documents required by William the Conqueror. The book recorded the king’s allotment of properties to his subjects. As the king owned all land within his rule, he collected rent and imposed taxes and maintained an accurate record of all financial matters.

The British became adept at assigning titles of nobility and with such titles, various properties and accompanying castles. A gentleman by the name of William Montgomery spent years researching the various Montgomery clans in Scotland. His centuries old work, the Montgomery Manuscripts is a bedrock in current pedigree charts. The Thomas Montgomery 1861 publication A Genealogical History of the Family of Montgomery: Including the Montgomery Pedigree is also a great source of information related to colonial America and British roots. David B. Montgomery (D.B.) authored a similarly titled text, A Genealogical History of the Montgomerys and Their Descendants pertinent to the ancestors of our Matilda Montgomery (wife of Peter Smith of Posey). The work of several other British historians provides a significant cache of information upon which one can grow a family tree. The Montgomery line fizzles out in our American tree with the marriage of Matilda Montgomery (1808-1874) and Peter Smith of Posey, early settlers in Posey Township, Indiana. They were my father’s great grandparents.

D.B. Montgomery tells us that Matilda was the second of James Montgomery’s children. She married Peter Smith in 1825 when she was all of 17 years of age. She immediately turned into a machine capable of turning out babies on a continuous basis, thirteen of them in all. Not all of Matilda’s children made it to adulthood, but those that did continued their parent’s propensity for creating life. Child number 12, James Monroe Smith was my father’s grandfather.

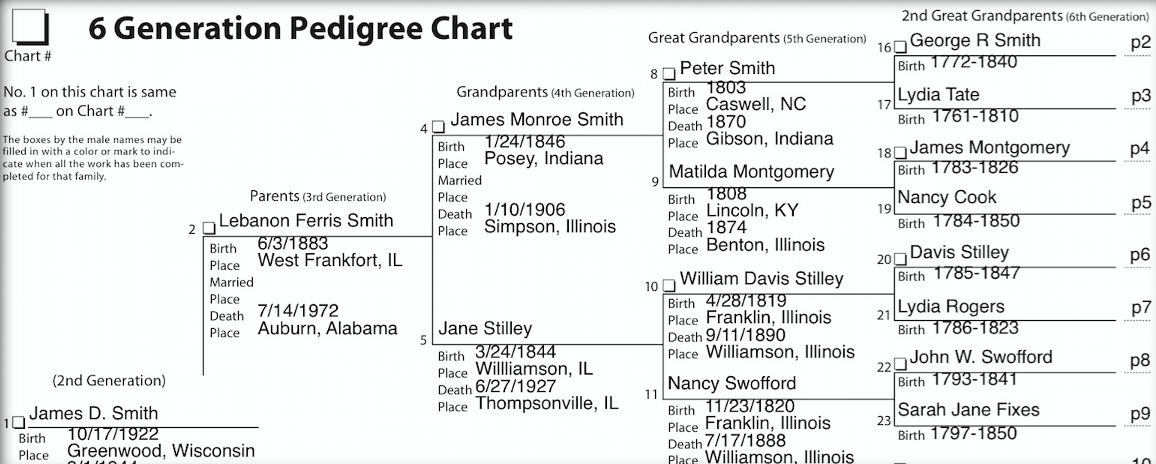

The Montgomery/Smith lineage, leading to my father, looks like this:

Pedigree Chart 14: The Montgomery Family 1783-2003

Matilda Montgomery occupies seat #9 in Aisle 4. She is noted as my father’s great grandparent. Matilda was the daughter of James Montgomery (1783-1826) and Nancy Cook (1784-1850).

For those who have never studied a page from a 19th Century volume of family genealogy or riveted an eye on a page of progeny, allow me to introduce you to the efforts of D.B. Montgomery. Keep in mind, this selection only represents the family of Matilda Montgomery. D.B took each of Matilda’s siblings and created a similar sketch for each of the children and grandchildren of her brothers and sisters. He did the same for each of her aunts and uncles. These efforts are incredibly rich with history and detail involving our forefathers. D.B. personalizes the history of mankind. But I will be the first to admit, I can only handle these snippets in small doses before I finally snap, run down to the banks of the Embarrass River and douse my head in the cold spring fed waters.

The following information regarding the family of Matilda Montgomery and Peter Smith of Posey is copied verbatim from the manuscript of D.B. This entry constitutes only 2 of the 436 pages of similar detail D.B. authored.

“Matilda Montgomery, born Oct. 8, 1808; died March 10, 1874; second child of James Montgomery, Sr., married Peter Smith, 1825; he was born Oct. 17, 1803; died Dec. 15, 1870;

Children, thirteen:

-

- infant

- Nancy Smith, died at two years old

- infant

- America Smith, married Charles Cleveland; children eleven.

- Sarah Ann Smith, fifth child of Peter Smith, married Robert Eaton; children eight: 1, Peter Eaton, married —. 2, Harriet Eaton, married John Eaton. 3, Matilda Eaton, married —. 4, Elizabeth Eaton. 5, Louisiana Eaton, married a Mr. Jones. 6, Indiana Eaton, twin to Louisiana, married a Mr. Jones. 7, Levina Eaton. 8, Nerva Eaton.

- Mary Smith, sixth child of Peter Smith, married Robert Eaton; children three: Louisa Eaton; —, —,

- Gilbert L. Smith, died 1832, seventh child of Peter Smith, married Jane Jordan; children five: 1, Thomas J. Smith; 2, Matilda Smith; —,—, —.

- Patsy Smith, born Oct. 29, 1834, eighth child of Peter Smith, married George Finch, March 13, 1851. He was born July 18, 1829. They settled in the neighborhood of the Providence church of Regular Baptists, in Gibson county, Ind. Mr. Finch was county commissioner three years. They celebrated their golden wedding in 1901, and she carries, as the testimony of love and respect of her children, a nice gold watch presented on that occasion. Children 13: 1, William P. Finch, married Lucinda Spencer; children four: George W. Finch, Belle Finch, infant and Amy Finch. 2 and 3, Lemira J. and Matilda A. Finch, dead. 4, Isabella Finch, married James Holcomb; children five: Jefferson, Arel, Lester, Jesse, —. Malinda A. Finch, fifth child of Patsy Finch, married Charles Holcomb, a lawyer and ex-judge of Broken Bow, Neb., and a brother to ex-Governor Holcomb of Nebraska: children five: 1, Wilber, married. 2, Versa. 3, Mabel. 4, Edna. 5, Roy. James F. Finch, sixth child of Patsy Finch, married Ellen DePriest; children eight: 1, Myrtle. 2, Clauda. 3, Zelmie. 4, Roy. 5, Lester. 6, Carl. 7, Effie. 8, Edna. Ida May Finch, seventh child of Patsy Smith, married Calvin Glaspie; children five: 1, Clauda. 2, Ethel. 3, Bertha. 4, Lora. 5, Flora. Nancy Ellen Finch, eighth child of Patsy Smith, married Harry Morrison; children six: 1, Lelia. 2, Arthur. 3, Verdia. 4, Bessie. 5, Herral. 6, Lula. Oscar Finch, ninth child of Patsy Finch, married Emma Hutchinson; children three: 1, Onie. 2, Arvel. 3, —. John S. Finch, tenth child of Patsy Finch, married Nannie Rana; children five: 1, Oscar. 2, Zetteda. 3, Mabel. 4, Rosa. 5, Willis. Bertha D. Finch, eleventh child of Patsy Finch, married George Gladish; children two: 1, infant. 2, Ray. Ella E. Finch, twelth child of Patsy Smith, married Louis Seaman; children two: 1, Virgil; 2, Eunice. John W. Finch, thirteenth child of Patsy Smith, taught in the public schools; married Stella Strawn; children two: 1, Jesse; 2, Patsy.

- Thomas J. Smith, ninth child of Peter Smith, died at 21 years old.

- George F. Smith, tenth child of Peter Smith, died at 18 years old.

- Lucinda Smith, eleventh child of Peter Smith, married Wm. McGee. She died in Arkansas: children two: 1, Wm. M. McGee, a druggist in northern Indiana; married Emma McFredrica; children two boys. 1, James W. McGee, married Adaline Reavis; children three.

- James M. Smith, twin to Lucinda Smith, twelth child of Peter Smith, married Jane Stelley; children five: 1, Peter; 2, Matilda; 3, Nancy

- John Mac Smith, thirteenth child of Peter Smith, first married Julia Wilson; children two: 1, George F. Smith; married Anna Heironimous; children one- Roy Heirnoimous. 2, Thomas J. Smith, son of John Mac Smith. Second, John Mac Smith, thirteenth child of Peter Smith, married Anna McReynolds; no children.”

Did you find Great Grandfather James Monroe Smith hiding in there (at #12) as a twin of Lucinda? The author (D.B.) was not aware of the additional children found in the home of James Monroe and Jane Stilley Smith. Imagine, all of these individuals sprang from one couple: Peter Smith of Posey and Matilda Montgomery. Did you notice that a guy named Robert Eaton married first Sarah Ann Smith (#5) and then her sister Mary (#6)? One assumes Sarah died ‘giving birth’ during that time period. Divorce was uncommon, although, my father believed our own James Monroe Smith (#12) “took French Leave” from his wife Jane and saw his marriage to Jane Stilley end in divorce.

Obviously, the author (D.B.) had close ties to Patsy Smith (#8), a daughter of Matilda. The detail and delineation of Patsy’s offspring is profuse. I haven’t checked, but the Clan Montgomery Society (on the web) may still be selling reprints of this book. OK, so it isn’t compelling reading, a bit like battling one’s way through the Book of Genesis with all the begetting going on from one generation to the next. But you get the drift of how these tomes are laid out.

In that lengthy summary paragraph regarding Patsy (#8), notice the proud reference to a brother-in-law, Charles Holcomb, who happened to be the brother of a former governor of Nebraska. It’s what we do with these bits of history. We puff up our chest a tad, have an “Aha!” moment and then realize the insignificance of it all. Why has it come to a point that being the wife of a brother of a former governor is any more important or relevant than the two forgotten children of Mary Smith (#6 above) and Robert Eaton? And, oh by the way, these Eatons, they descended from the Eaton gentleman found on the Mayflower. We now worship celebrities to the point that we elect them President of our nation.

Here’s another thing I do when I leaf through such notes: Patsy Smith married a Finch, George Finch. One of my favorite performances in a movie, Network, found Peter Finch playing crazed TV anchorman Howard Beale in a very disturbing and all too real scenario: “I am mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore!” Is it possible Peter Finch descended from Matilda Smith Finch? The answer in this case is ‘no’. Peter Finch was born in Britain in a long lineage of Brits. None of Patsy’s descendants returned to live in England.

But guess who I did find lounging in a hammock in the Montgomery tree branch with us?

Mark Twain

It’s a reach. But yes, more than one hundred years ago a subscriber to D.B. Montgomery’s efforts queried D.B. regarding Mark Twain. How the investigation into Twain’s lineage began was as interesting as the findings that resulted.

As he gathered information, D.B. traveled by rail and relied on the U.S. mail service. He wrote letters of inquiry to numerous Montgomery families. He encouraged correspondence. He operated like a 21st Century family blogger, sharing data, posting queries and fact checking. What I find in cyberspace, D.B. found on paper, what we now call the ‘hard copy.’

D.B. received a letter from a fan in Missouri asking if he could validate a family story regarding family ties to Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens). The letter writer implored D.B. to ask Twain, should they cross paths, if Twain was a descendant in the Montgomery family. The letter writer assumed too much. D.B. Montgomery, though an author, was not traveling in the same circle with Twain. While alive at the time, Twain was not about to create family ties with avid readers of his great works. Knowing human nature as he did, Twain could have only imagined how many devotees would soon be clamoring to visit him to renew family bonds. He could no doubt picture ‘lost cousins’ dropping in for the weekend, using his family bath and enjoying some of the wealth Twain had acquired. D.B. did contact Twain but received no response.

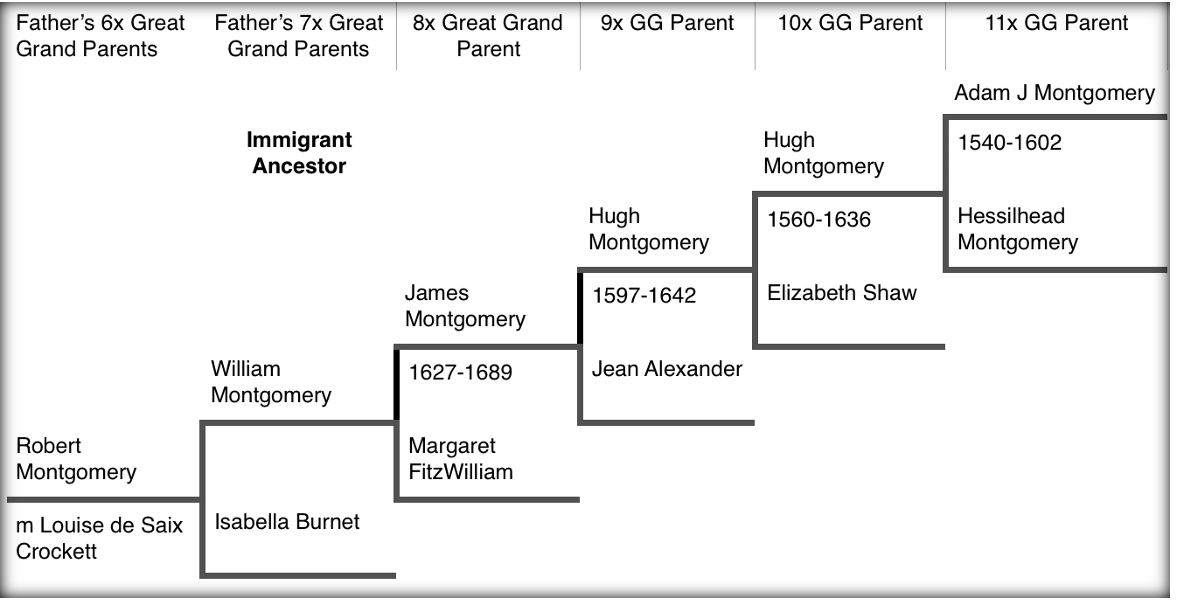

D.B. did uncover the following distant connection: Mark Twain and I share my 6th great grandparents, Robert Montgomery and Louise de Saix Crockett Montgomery. I will invite the transcendent author to our next family reunion. We could use another good story teller at the firepit. Oh wait! Twain died a century ago.

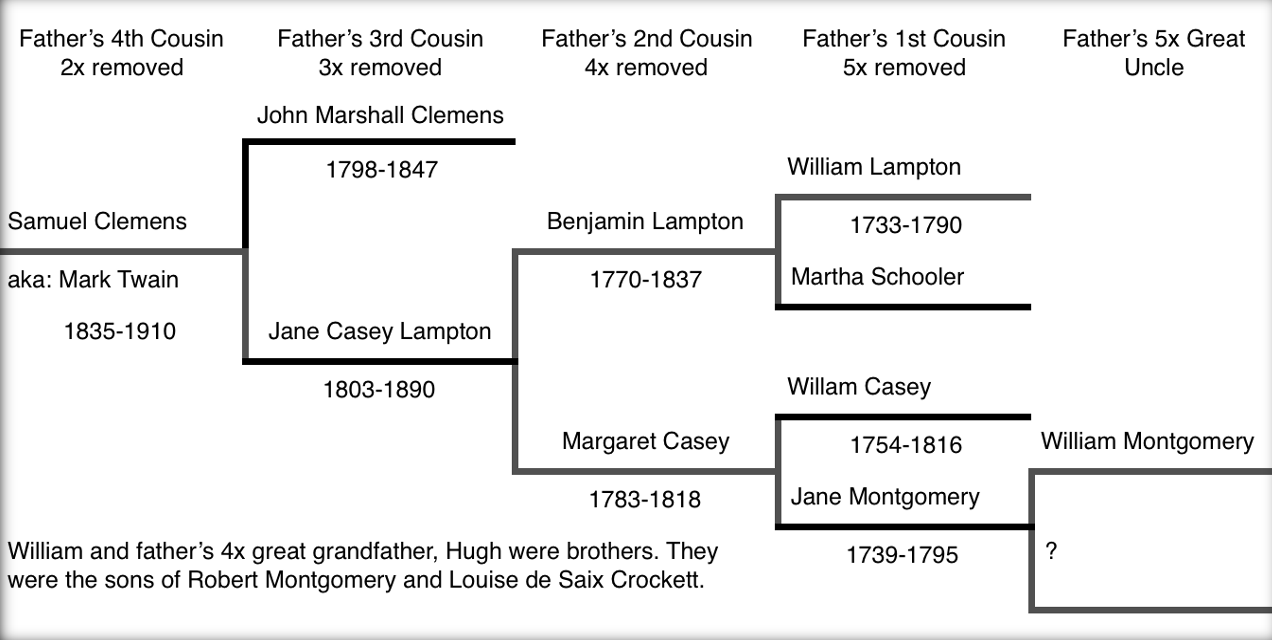

Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens) is my father’s fourth cousin, 2 times removed. My father descended from Robert Montgomery and Louise de Saix Crockett as did Twain. Robert Montgomery was Twain’s great great great grandfather (also written as 3x GGF). Robert was my father’s 5x GGF. My father’s 4x GG Parents were Hugh and Caroline Montgomery. Twain descended from Hugh’s brother, William. The header of each column in pedigree chart #16 identifies the relative in bold and their relationship with my father. As an example, Margaret Casey is my father’s second cousin, 4x removed. Benjamin Lampton does not descend from Robert Montgomery and Louise. Therefore, he is not a cousin and would be referred to in genealogy as the ‘husband of a second cousin 4x removed.’

Pedigree Chart 15: Mark Twain’s Descent in the Montgomery Tree

Not to make excuses for Twain’s failure to respond to D.B., but Twain and his mother Jane Casey never knew Jane Montgomery. Jane Casey had been born after her grandmother, Jane (Montgomery) Casey died.

Let’s cut Twain some slack. He knew a bunch about life on the Mississippi River, but squat about his grandparents. If Twain had known of a Scottish Highlander, the Third Viscount Montgomery and his amazing open heart, I am certain the author would have created one heck of a story concerning the man’s exploits. Okay, so I haven’t told you about a Great Uncle Hugh III and his amazing open heart? Let’s head overseas to Great Britain and the year 1066 and I will eventually lead you to Hugh, the Third Viscount Montgomery of the Great Ards. We will filter through the ages and return to Matilda Montgomery, Peter Smith and Posey, Indiana.

Let’s head back 1000 years. Set the time machine, Wilbur. Our favorite home brew specialist, Wilbur Rancidbaatch always drops by with another of his latest concoctions. I am his one man focus group. If I live through a pint, he feels comfortable feeding it to his dogs and friends.

Sir Roger de Montgomery, First Earl of Shrewsbury (1022-1094)

Father’s 25x GGF, Normandy and Shropshire, England

In a recent visit to England, more specifically Shrewsbury, I stayed in a city once ruled by my father’s 25th great grandfather, Sir Roger de Montgomery, First Earl of Shrewsbury. Born in 1022 in Saint Germain de Montgomery, Calvados, France, he was a confidant of and advisor to William the Conqueror in 1066. He was a top commander of William’s military force. While Roger was a major player in armed conflicts his toughest opponent and most insane battles were with his own wife, Mabel de Talvas, (b 1026 in Orne, Basse-Normandie, France).

Roger’s father, Roger de Montgomery, seigneur of Montgomery, controlled beaucoup acres in the valley of the Dives in central Normandy (France). Junior was the third but eldest surviving son of Roger de Montgomery and thus inherited his father’s estate. Roger Jr’s role in the Norman invasion of England in 1066 is subject to debate. Wace’s, Roman de Rou, depicts Roger as the commander of the right flank of the Norman army in the Battle at Hastings, returning to Normandy with the victorious King William in 1067. Excerpts of Wace’s account of the Battle of Hastings can be found online. Wace clearly depicts Roger in a tight relationship with William the Conqueror. Wace provides lengthy dialogue between the two great warriors as they scan the battlefield at Hastings. Their English was impeccable and rather Shakespearian in nature, long before there ever was a Shakespeare, and long before the Norman lords had acquired English as a second language. But Wace writes as if he too was there as a scribe, a witness to every detail.

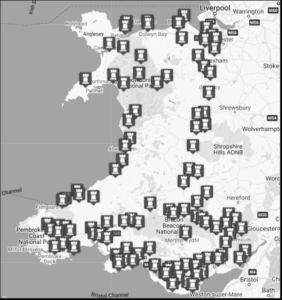

Other more recent authors believe Roger (1022-1094) was directed to remain in Normandy in 1066 as provisional leader of the kingdom in the absence of the Conqueror. He was to ride herd on any local insurrections and challenges to William’s throne. For his service and loyalty to William, Roger was entrusted with land in two places critical for the defense of England: Arundel and Shrewsbury. The Shropshire territories, home to the Marcher Lords, stood between Wales and England. The territory was rife with constant warfare. Raping, pillaging and murder were a common source of entertainment. Mayhem was the norm. Few places in Europe were littered with more hilltop forts, fortresses and castles than the Welsh border with England.

Iron Age (1200 b.c – 700 a.d.) fortresses like Ffridd Faldwyn stand near the Montgomery Castle (1072 a.d.), in Montgomeryshire, Wales, just to the west of Shrewsbury. Montgomery Castle is one of the finest examples of the motte and bailey castles, surviving for one thousand years. It was built by Roger in his effort to secure the border. He then took things a step further and invaded Wales.

Prior to the Norman invasion the 8th Century Saxons, under the command of Offa, constructed 150 miles of dyke intended to mark a border that Saxons and Welsh were expected to respect. “Cross the line and you are dead meat!” seemed to be the mantra of the day. Or as one Welsh ruler shouted across the distance to a Saxon lord: “Your ass will be my haggis if you cross this wall.” A 21st Century rap version of the lyrics can be heard on the DJ Caber Haggis album 2Much2Eat. (Not true).

Whether Sir Roger delivered the decisive attack at Hastings or governed Normandy in the absence of William the Conqueror, one fact is certain: Roger was rewarded for his effort. He became one of the five most wealthy men in England during the reign of William the Conqueror. His possessions included the county of West Sussex (Arundel and Chichester), 83 manors in Sussex, seven-eighths of Shropshire, 30 manors in Staffordshire, 11 manors in Warwickshire, 9 manors in Hampshire, 8 manors in Middlesex, 8 manors in Cambridgeshire, 4 manors in Surrey, 3 manors in Wiltshire, 2 manors in Worcestershire, and 1 manor in Gloucestershire. These shires are scattered about England, and Sussex itself, hugs the English Channel to the south. The income from Roger’s estates amounted to an equivalent of £2000 per year in 1086 at a time when the landed wealth for England was reported as £72,000 in the Domesday Book. Roger’s wealth was roughly 3% of the nation’s GDP. He was set for life. There was however, the matter of his wife’s disposition and William’s propensity for shifting deeds from crony to crony.

Roger’s wife, Mabel de Belleme (aka Mabel de Talvas), the daughter of William (Guillaume) II Talvas Compte de Balleme and Hildeberge de Beaumont was reportedly obnoxious, overbearing, ruthless and power hungry; not a pleasant bridge partner. One author described Mabel as

“An exceedingly cruel woman. While not very large in stature, she made up for it in bold schemes and pure wickedness. In an attempt to poison the son of a man responsible for blinding and mutilating her equally cruel father, she managed to kill her husband’s youngest brother, Gilbert, instead.”

That caused Roger to think twice about irritating his wife. Mabel’s father, William de Talvas, was equally wicked and despicable. He had married a Hildeburg, the daughter of a nobleman named Arnulf. William had his wife assassinated, strangled on her way to church, according to the Montgomery family historian of the 11th Century, Orderic Vitalis. Hildeburg was executed because she loved God and would not support her husband’s wicked attacks on their neighbors.

Talvas married a second time, choosing for his bride the daughter of Ralf de Beaumont. Talvas invited a vassal he loved to abuse, William fitz Giroie, to attend the festivities. Suspecting nothing fitz Giroie came to the celebration expecting to enjoy whatever Halvas was providing. Little did he know that he would be the macabre event of the year. He was seized by Talvas’ men, imprisoned, then according to Orderic horribly mutilated and blinded before being released. Somehow, he survived the abuse, but spent the remainder of his life sequestered in a monastery fa removed from the reach of William de Talvas. Events like these caused a backlash in the community and Talvas became a marked man.

Mabel was known to exercise a considerable amount of power in her native Normandy. Her antics caused many of her husband’s best buddies to lose their possessions and end up flat broke. It was her malice toward one specific family that brought about her brutal demise. Using her authority, she denied the Bunel brothers access to their father’s fortune at his death.

The Bunel brothers provided a very shocking end to Mabel’s life. In December of 1077, they mounted their horses, rode into her castle of Bures-sur-Dive and cut off her head as she rested in bed after a bath. Roger rebounded from the loss ofhis wife and married Adelaide du Puiset. By all reports he gained some semblance of serenity in his declining years. It is not reported that he sought revenge or even justice in the matter of the Bunel attack on Mabel. Roger was conveniently away on business, living in Shrewsbury, at the time of the attack in Normandy.

Roger de Montgomery was a devoted Catholic and his contributions to the church and abbey in Shrewsbury were generous and numerous. Mabel on the other hand was a painful experience for any member of the clergy regardless of their stature. She would purposefully visit her husband’s abbey in Shrewsbury with an entourage large enough to drain the limited resources of the abbey. The abbot told her if she did not mend her ways, she would suffer great pains, which evidently happened as she left quickly that evening and never returned. It has been suggested by some that the kitchen staff served a meal that wrenched on the gut of the wench and caused her to wretch. Say that three times, fast, with your hand pressed firmly against your gut.

Roger and Mabel had married in 1048 in Perche, France. The marriage bound together two of the larger land holdings in all of Normandy. The marriage did more than bind wealth together and the evidence for that is found in the fact that Roger and Mabel had the following children:

Robert de Bellmeme, Earl of Shrewsbury

Hugh de Montgomery, Earl of Shrewsbury

Roger, Vicomte d’Heimois

Philip de Montgomery

Arnulf de Montgomery

Sibyl, wife of Roger FitzHamon

Emma, Abbess of Almencheches

Matilda, wife of Robert de Morton

Mabel, wife of Hugh de Chateauneuf

A second Roger died young

Our family descends from Arnulf. His siblings are great aunts and uncles. I prefer Arnulf to the eldest son, Robert de Belleme, who inherited his mother’s tendencies for savagery. Research revealed that Arnulf was equally despised by the Irish whose villages he conquered and ruled through fear and loathing. He was so despised that his father-in-law poisoned him at a Welcome Home Arnulf fest. Arnulf failed to wake the next morning.

Roger de Montgomery’s life was far from ordinary. He was caught up in the drama of life at the side of William the Conqueror. He was instrumental in bringing about peace between King William the Conqueror and Fulk of Anjou. The Fulk was a half-brother to William Rufus and had his heart set on ruling Normandy. Roger also helped reconcile William the Conqueror and William’s son, Robert Curthose. Robert’s rebellions against his father began when Robert was a teenager. He was the runt of William’s litter and took the usual abuse handed down by siblings. Robert was incensed when his brothers dumped the family chamber pot (poop pan) on his head. When his father failed to discipline the older boys for their mischief, Robert turned against his family and went so far as to flee the home, seeking refuge with uncles and fomenting insurrection among those who could benefit from the demise of King William. Roger Montgomery was able to bring the two men, William the Conqueror and son Robert Curthose, together for a short time.

At his death, King William the Conqueror, presented his oldest son Robert Curthose with Normandy and William Rufus with Great Britain. At first, Roger Montgomery and his sons, supported Rufus in his efforts to maintain control of England, Scotland and Wales. Noblemen who held lands in both Normandy and Britain faced a dilemma. William Rufus and Robert Curthose were natural rivals ruling powerful countries within Europe. Noblemen like Montgomery were caught between two brothers who had a history of confrontations.

Sir Roger and his sons rebelled against the rule of William Rufus, in support of Robert Curthose. After a decade of rule, William Rufus met his death in a “hunting accident” in the New Forest. The event was eerily similar to the death of William’s brother, Richard, 25 years earlier in the same location of the New Forest. The suspect in the murder of Rufus was his brother Henry, the youngest of the brothers, who immediately had himself anointed King of England.

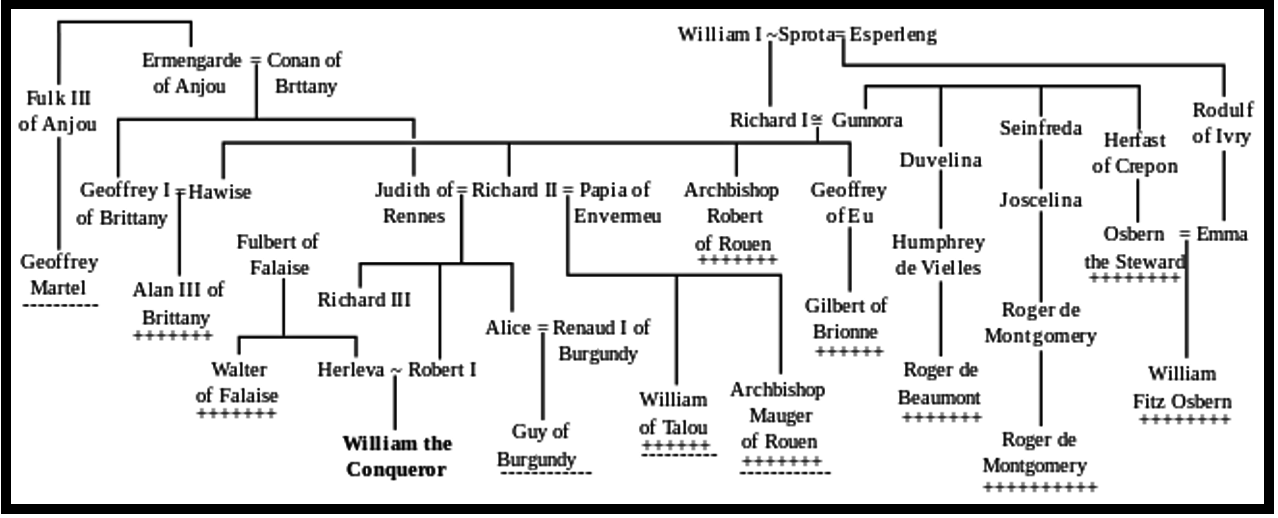

Roger Montgomery actually had a legitimate claim to the throne at the time of the Conqueror’s death in 1087, but nearing the end of his life, chose to ignore his claim. Roger’s position in the royal family of William the Conqueror is noted in the chart that follows.

Pedigree Chart 16: Roger de Montgomery and Wm the Conqueror

To the right of Roger de Montgomery, you will find the name of William Fitz Observe. It is believed, but not yet proven, that the Osbun/Osburne line in my wife’s Sullivan family links back in time to this Osbern. That’s a story for another day, a different book.

As the war for control of the throne played out Roger sensed that William Rufus would be the eventual winner. Roger deserted Curthose and gave his considerable support to William Rufus. Roger jumped ship just in time, but not without consequence. Curthose held Roger’s sons hostage and prepared to attack Montgomery’s castle at Belleme. Roger eventually negotiated a safe return of his sons. William Rufus won his war with his brother Curthose and imprisoned him for life. Rufus stripped rebels like Odo of Bayeux, Eustace III, Count of Boulogne, Robert de Mowbray, Geoffrey de Montbray, and Robert de Mortain of their properties and entitlements. Several of these names including Robert de Mowbray, a 24th GGF, are found in the family tree.

Roger built Montgomery Castle fifteen miles to the west of Ludlow, Shropshire, in 1086 and led an invasion into Wales after the death of Rhys ap Tewdwr in 1093. Tewdwr (aka Tudor) the ruler of the Welsh kingdom of Deheubarth, is also found in our family tree as a many times GGF. The Tudor monarchs of England descend in part from Rhys. Roger built castles at Cardigan and Pembroke, securing Deheubarth under his control once he defeated the Welsh armies. Illness got the better of our great grandfather in 1094 and he developed the notion that his days were numbered. Fearing that he was nearing death, Roger entered the monastery at St Peter and St Paul Abbey in Shrewsbury where he begged forgiveness, thought divine thoughts and followed holy orders. He died three days later, on July 27, 1094. He was buried at the very abbey he had founded; the same abbey that failed to sufficiently poison his wife in previous years!

With the death of Roger de Montgomery, his son Robert inherited Normandy, Hugh received English estates and the title of Second Earl of Shrewsbury. Hugh soon died of a fatal arrow that flew through the eye slit of his helmet during an attack against King Magnus of Norway. Legend has it that the shot was fired by the King himself. The entire family estate then fell to Hugh’s brother, Robert de Belleme, Third Earl of Shrewsbury. It is interesting to note that one thousand years later the Montgomery family still made heavy use of the first names, Roger, Robert, William and Hugh when naming their sons.

Family Feuds

While my intent with this collection was to focus on my father’s family history, I am reminded from time to time that I am writing this book for the edification of my son and my descendants. Whether they are edified is entirely beyond my control. At any rate, for my siblings and my nieces and nephews, I beg your pardon here and digress into a brief review of my wife’s ancestors during the era of early England. It is a strange experience for me to find her ancestors basically at war with mine, seizing properties, raping, pillaging and creating mayhem.

Roger de Montgomery found himself at odds with my wife’s ancestors in the hills and vales of Wales and Shropshire. As William the Conqueror’s need to defend his turf grew and his number of enemies increased, he found it necessary to subdivide the properties he had initially portioned out to his Norman mafia. Around about 1086 he took some of Roger’s Sussex land and formed a fiefdom for William de Braose, with its center at William’s castle of Bramber. The Braose family Bramber Castle was in Sussex on the English Channel. William “the Ogre” Braose is Nancy’s 26th Great Grandfather.

The Ogre’s grandson, William de Braose (24th GGF), lost his life at the hands of my father’s 22x great grandfather Llywelyn (the Great) ap Iorwerth (1173-1240). Llywelyn is also my wife’s 23x GGF on both sides of her parent’s families. Her father descends from Robert the Bruce. Her mother descends from King John I (Lackland), father of Llywelyn’s wife, Joan. Lackland is my wife’s 23x great grandfather. I put Llywelyn the Great up on a pedestal with Scotland’s William Wallace and Robert the Bruce. He stood toe to toe against the English kings and beat them at their own game.

William de Barose made a fatal mistake while staying at the home of his friend Llywelyn’s castle. The Good Welsh prince returned a little earlier than expected from a round of mayhem and bloodshed, only to find his wife (King John’s daughter, Joan) in bed with de Braose. Joan, the Princess of Wales, is my wife’s 22x great grandmother. Fornication with the King of England’s daughter was a federal crime and William de Braose paid the price. Llewelyn executed him in such a way that it sent a message. I will skip the details. Suffice it to say, de Braose was never quite the same again. Joan was confined to prison within Llywelyn’s castle for one year and then forgiven. This Joan is not to be confused with her half-sister, Queen Joan of Scotland (1210-1237).

I visited one of Llywelyn’s homes at Caernarfon Castle in the north of Wales. It is a majestic fortification and a favorite spot for travelers who enjoy a view of the sea. It was cool thinking that I had a great grandparent who chilled out in the confines of such a man cave. As my wife and I are both descended from this Welsh warrior we wanted the keys to the front door of the castle.

A guy named William de Warenne was also given some of Roger Montgomery’s land to the east in Sussex. I mentioned Chichester earlier in this dung heap of history and I should point out there was no castle positioned at Chichester until 1142, when Nancy’s great grandfather King Henry I (26x GGF) built a fortress on what had been Montgomery property. Roger’s son, Robert de Belleme, forfeited his claims to any and all estates in 1102 when he wound up on the wrong side of insurrection. Belleme would be a 26x great uncle of mine if I hadn’t disowned him.

William de Warrene is Nancy’s 24th great grandfather and he was married to a more important figure in English history, Lady Maud Marshall (1192-1248). Maud’s father, William Marshall of Pembroke (1146-1219), Nancy’s 25th GGF, served five English kings – The “Young King” Henry, Henry II, Richard I, John, and Henry III. He was knighted in 1166 and spent his younger years as a knight errant and a successful tournament fighter. Stephen Langton eulogized him as the “best knight that ever lived.” On his deathbed, William Marshall, invested heavily in an upstart organization known as the Knights Templar. This Catholic structure became the world’s first multinational corporation, an early version of Blackwater, dedicated to the Crusades, accumulating wealth and evolving into an international banking and money laundering system.

Grandchildren of William Marshall included Robert Bruce I, Humphrey de Bohun, Gilbert de Lacy and the infamous Roger Mortimer. The equally infamous Simon de Montfort marries William Marshall’s widow. These people occupy a place in my wife’s family tree. I think my ancestors, other than Roger Montgomery’s line, might have been shearing sheep in Wiltshire and moving rocks around a garden plot in Ireland to prepare a meager harvest.

The death of King Henry I (Nancy’s 26x GGF) plunged England into twenty years of turmoil. The Brits refer to this epoch as the Years of The Anarchy. Much of the original Montgomery estate surrendered by Belleme was acquired by William de Aubigny (1109-1176) (Nancy’s 24th GGF) upon his marriage to Adelize, widow of King Henry I. William de Aubigny garnered the titles Earl of Arundel, Chichester and Sussex in 1156, when Henry II rewarded him for his loyalty during The Anarchy. Barons like de Aubigny enabled Henry’s ascendancy to the throne.

These are only a few of the ancestors (from the 11th and 12th century gathered around the Great Snooker Table in the sky. There are many more. The DNA of these royal members of my wife’s tree was brought to the New World by two men: Nathaniel Littleton (Whittingtons) and Obadiah Bruen (Sullivans). They arrived in America circa 1638. We visited their respective British homes in Tarvin (Bruen) and Ludlow (Littleton).

The British Montgomery Lineage

I use the term ‘British’ loosely, to include all kingdoms contained on the British Isles over the centuries: England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, Ulster, Powys, Deheubarth…

There are, following the death of Roger de Montgomery, the First Earl of Shrewsbury, a string of less wealthy, less powerful Montgomery men and women who dot the British countryside like sheep in pastures over the centuries. The spelling of the last name changed from one generation to the next during the millennia. Genealogists have found over 40 spellings of the surname. For the sake my sanity I have used the spelling ‘Montgomery’ in every instance in the pedigree found on the next page. Using the work of several of the authors previously mentioned I have constructed a lineage that appears to be accurate.

The British tree, documented from the year 800 AD to the Virginia immigrants in 1666, can be found in the work of William Montgomery (Montgomery Manuscripts, 1680) and the work of Thomas Harrison Montgomery (1863). The volume Thomas produced is extensive, involves many clans, and in several instances, requires a reader to connect the dots, so to speak. There is absolutely no humor found, no humor whatsoever. It is as dry as the Platte River of Nebraska in August. And no references to haggis, cabers or the Loch Ness Monster.

Our European roots take us back to the Norse Vikings and carry us through some characters whose names show up in the archives of history. As with all family history one may find critics of the efforts of D.B. and Thomas Harrison Montgomery. It is impossible to quiz either man, considering the sands of their hourglass came to rest a century ago. With that in mind, consider the effort such authors made without benefit of the internet, telephone or air travel. They traveled by carriage or ship. They poured over loose-leaf documents, courthouse records, family Bibles and pages of manuscripts produced by previous generations of family history buffs/addicts.

As I entered the names of all these grandfathers and grandmothers, I noticed a pattern: Montgomery men preferred women named Margaret. There are 30 wedded couples on pedigree chart 18 and eight of the wives are identified as ‘Margaret.’ One cannot ignore the women in this family tree. Many of the families represented by the wives have their own illustrious history, as we have discovered by exploring the history of our own Matilda Montgomery.

The Douglas clan, Campbells, Cunninghams and Colquhouns (Calhouns) all bring vibrant histories to our family tree. And who could ignore the name Elizabeth Hepburn and not wonder if Katherine and Audrey could be out there on the end of a branch in our tree. I for one choose to ignore the possibility. I do know for a fact that Audrey Hepburn was a stage name.

Let’s see if it is possible to place the complete lineage of Sir Roger de Montgomery, leading up to my father and his offspring, on this one page.

Pedigree Chart 17: Sir Roger de Montgomery

1st Earl of Shrewsbury (1022-1094) m Mabel de Bellmen et d’Alcencon Halvas

- Arnauf Cimbricus Montgomery (1066-1120) m Lafracoth O’Brien

- Phillip Cimbricus Montgomery (1101-1177) m Margaret Fitz Cospatrick

- Robert Montgomery of Eaglesham m Marjory Stewart FitzAlan

- John Montgomery (1155-1239) m Helen de Kent (1158-)

- Alan Montgomery (1199-1234) m Casillas Stair (1199-1255)

- John Montgomery (1220-1285) m Margaret Murray

- John Montgomery (1265-1328) m Janet Erskine

- Alexander Montgomery (1305-1380) m Margaret Douglas (1308-1374)

- John Alexander Montgomery (1343-1401) m Elizabeth Eglantine

- John Montgomery (1363-1429) m Margaret Maxwell

- Alexander Lord Ardrossan Montgomery (1381-1470) m Margaret Boyd

- Alexander Montgomery (1428-1452) m Elizabeth Hepburn (1430-1448)

- Robert Montgomery (1448-1468) m Jean Campbell (1444- )

- Alexander Robert Montgomery (1464-1505) m Elizabeth Cunningham (1474-1557)

- Adam Robert Montgomery (1480-1558) m Margaret Mure (1500-1576)

- Adam John Montgomery (1515-1576) m Elizabeth Colquhoun (1516-1576)

- Adam Montgomery (1540-1602) m Margaret Hessilhead Montgomery (1535-1570)

- Hugh 1st Viscount Montgomery (1560-1636) m Jane Shaw (1560-1625)

- Hugh 2nd Viscount Montgomery (1597-1642) m Jean Alexander (1606-1670)

- James Montgomery (1627-1689) m Margaret FitzWilliam (1625)

- William Montgomery (1650- ) m Isabella Burnet

- Robert Montgomery (1678-) m Louise de Saix Crockett

- James Montgomery (1695-1756) m Anne Thomson

- Hugh Montgomery (1713-1778) m Caroline Anderson (1715-1767)

- Samuel Montgomery (1743-1815) m Mary Polly McFarland (1753-1819)

- James Montgomery (1783-1826) m Nancy Cook (1784-1850)

- Matilda Montgomery (1808-1874) m Peter Smith (1803-1870)

- James Monroe Smith m Jane Stilley

- Lebanon Smith m Mary Hughes

- James Donald Smith m Doris Christine Weiherman

- Children of JD and Doris

Pedigree Chart 18: Our Montgomery Ancestors in Great Britain

Where to begin? Let’s focus on the last few generations of Montgomerys in Great Britain. To the left we have the immigrant ancestor in the American colonies, William Montgomery and his parents James and Margaret Montgomery of Scotland and/or Ireland. James and Margaret were the parents of three sons who migrated to Virginia: Hugh, William and Robert.

Hugh Montgomerie of Broadstain (1560-1636) and Elizabeth Shaw

Father’s 10x Great Grandparents, Dunskey Castle, Wigtownshire, Scotland

Out of respect to the author, Thomas Montgomery, I will plagiarize profusely from his work and because plagiarism was once thought to be a corrupt practice I will give him credit for his efforts and then butcher his narration, suppress his antiquated style of writing and infuse the following paragraphs with my own raw voice and rare flare for the pedantic.

Sir Hugh Montgomerie of Broadstain, 1st Viscount Mongomerie of the Great Aides (1560-1636) was an aristocrat and soldier. He is identified as a ‘founding father’ of the Ulster-Scots along with Sir James Hamilton, 1st Viscount Claneboye. Mongomerie was born in Ayrshire at Broadstain Castle, near Beith. He was the son of Adam Montgomerie, the 5th Laird of Braidstane and Margaret Hessilhead. (Note: Braidstane and Broadstain appear to be used interchangeably.) The time that Hugh spent lying in a cradle appears to be the only time that he was not at war.

His history as a soldier began in Holland (aka: Netherlands) where he became a Captain of Foot in the Scots Brigade under the command of the Prince of Orange. He remained in this service for a number of years and on the death of his father, Adam, in 1587, he returned to Broadstain.

In that same year (1587) he married his first wife, Elizabeth Shaw (1560-1625), the daughter of John Shaw, Laird of Greenock. Elizabeth and Hugh had a family of seven, four sons and three daughters. It appears from his track record that he had little time to play Nintendo with his children. He was a busy man, warring with his neighbors, maintaining family feuds and conquering the Irish.

Hugh was drawn into a centuries long feud with the Cunningham Clan in the hills of Ayrshire, Scotland when the Cunninghams assassinated the 4th Earl of Eglinton, a Montgomerie. Hugh pursued the suspected assassin from Scotland, through London, across the English Channel and into the Inner Court of the Palace at The Hague. He confronted Cunningham, drew his sword and struck him in the belly. He thought his blow killed the man right there, on the spot, in the pristine palace court. Hugh fled the scene, seeking to escape what he assumed would be murder charges, but was captured and detained. The victim, Cunningham, was saved by his belt buckle which deflected Hugh’s sword. Hugh was incarcerated in a Dutch jail awaiting trial when a fellow countrymen and Scot soldier, helped Hugh escape back to Ayrshire. He was heard commenting at a late-night poker game in Dunskey, “I’ll have to get me some of those belt buckles for our men!”

In 1603 Hugh accompanied King James VI of Scotland as James advanced on England from Scotland with the intent of securing the throne of King of England and Ireland as King James I. The death of Queen Elizabeth I in 1603 left a void in the monarch’s water closet and James hoped to fill it. James was the son of Mary, Queen of Scots, and a great-great-grandson of Henry VII, King of England and Lord of Ireland, positioning him to eventually accede to all three thrones: England, Scotland and Ireland.

James VI of Scotland succeeded in securing the throne of England and added the cool looking crown of England to his growing collection on the mantle of his man cave. The kingdoms of Scotland and England were individual sovereign states, with their own parliaments, judiciaries, and laws, though both were ruled by James in personal union until his death in 1625. I need to make clear that King James VI of Scotland is the same man as King James I of England and Scotland. In other words, there had been five guys before him who served as King of Scotland. But, when he also became King of England, he was the first King of England to have ever been named James. He apparently preferred living in England because he returned only once to Scotland in the last two decades of his life.

In 1605 Hugh Montgomerie was knighted by King James I. Prior to 1605 Hugh’s brother George had been installed by the King as the Dean of Norwich. He was made one of the ‘Chaplains in Ordinary to the King,’ a job that required a minister to serve the King’s spiritual needs. There were ten such chaplains in the court of King James. They were trusted advisors to the monarch. George was a conduit of information to Hugh and this served Hugh well as he secured the confidence of the King. Montgomerie’s friendship with the King came in handy when he set his eyes on establishing control of all lands within Counties Down and Antrim of Ireland.

The two counties, Antrim and Down, in this map of Ulster, are identified as ‘Scottish (privately settled).’ This was Irish turf seized by the Scottish aristocrat, Hugh Viscount Montgomerie I, with the backing of the English King, James I, himself a Scot.

Montgomerie acquired the property via negotiations with the wife of Conn O’Neill and the King of England, James I. The clan chieftain Conn had been imprisoned by Lord Chichester at Carrickfergus Castle for instigating a rebellion against the Queen Elizabeth I while she was in the latter days of her rule. Chichester seized control of all of Conn O’Neill’s kingdom and was awaiting an order from the Queen to execute Conn and claim Conn’s lands as his own. Unfortunately for Chichester, the Queen died, leaving Conn’s future in limbo. Conn’s wife, Ellis, seized the moment to save her hubby’s life and some part of his kingdom.

With James I now in charge of the land, Ellis O’Neill (the wife of Conn) approached the First Viscount Montgomerie (Hugh I) and struck a deal. Ellis would arrange a jailbreak at Carrickfergus, bust Conn out of the castle and deliver Conn to Hugh I. Hugh would then provide shelter for Conn and use his influence with King James I to secure a royal pardon for the Irish Chieftan. In return, the O’Neills would surrender half their properties to Hugh, First Viscount Montgomerie of the Great Ards of Ireland.

The jailbreak was successful, the King pardoned Conn and Montgomerie took control of Down and Antrim; but not without a hitch. A fellow Scot, James Hamilton, interfered with Montgomerie’s scheme and was able to convince the King that he should receive a share of the O’Neill land acquired by Hugh and Hamilton secured neighboring counties in Ulster.

Hugh and his brother George soon populated their holdings in Counties Down and Antrim with lowland Scots who crossed the channel from Portpatrick in Scotland to Donghadee. Hugh established the first ferry service to run at regular intervals between Portpatrick in Ayrshire to Donghadee in the Great Ards of Ireland.

It had taken the British four hundred years of warfare to ‘gain control’ of Ireland. Ulster had been one of the last of the Irish regions to succumb to British forces. Largely Catholic before the conquest, Ulster was soon flooded with protestants in 1606 and the Catholic Irish reduced in population and power. English law stripped the people of Ireland of land ownership. An Irishman could rent no more than 2 acres, barely enough for subsistent living. This was how the plantation of the Irish countryside began. Though their lands had been seized, wealth removed, schools closed and language muted, the Irish would not surrender their will and desire to be free. Though disenfranchised in every sense of the word the rebellions would never cease, the risings continued, and the spirit of the Irish people would never be crushed.

Hugh Montgomerie, 1st Viscount Montgomerie acquired Dunskey Castle in February 1620. It is reported in the exchequer (ledgers) of the time as

“10 librat of antiqui extentus de Portry” including “3 mercatas de Marok cum castro de Doneskey”

The “castro de Donesky” or translated “fort of Donesky” was a ward of the Adair family between the years 1426 and 1580 when William Adair, by way of a marriage contract presented the castle to Rosina MacClellan of Galston whose brother, Sir Robert McClellan married Mary Montgomerie, the eldest daughter of Sir Hugh Montgomerie.

On May 3, 1622, Hugh was created first Viscount Montgomerie of the Great Ards. Hugh and his first wife, Elizabeth Shaw, lived in relative comfort in what was a modest ‘castle’ propped up on a rock promentory overlooking the Irish Sea. The author of the Montgomery Manuscripts conveys the thought that Elizabeth was a warm and loving wife, enamored of her husband, comfortable in Dunskey and always a helpmate to Hugh. Her death in 1625 was apparently a blow to his wellbeing and marital bliss ended with her passing.

In 1625, Hugh married a second time to Sara Maxwell, the daughter of William Lord Herries (aka Maxwell), by whom Hugh had no issue. Present day descendants secured the child we needed, Hugh Junior, from Elizabeth Shaw before she passed away.

Sara Maxwell, the Viscountess Montgomerie, preferred living away from Hugh I and spent much of her time on her home turf. Historians note that she was seldom found at Hugh’s side nor in his company at Dunkskey. She was quick to point out the failings of Hugh’s abode and like a bird eager to build a better nest to attract his mate, he began making alterations in Dunskey.

Hugh made significant additions to the structure, adding the “Gallery” leading away from the “Great Hall.” He also added several vaults under the “Gallery,” but to no avail. On August 24, 1632, Sara Maxwell, wrote a letter to her loving husband Hugh:

“It seameth ye ar causing your workmen goe on both in your building and theikine of your Gallerie att Dunskay. They ar necessarie thing is to be outride, seeing ye have put theme so far agait. Bot I am suire they ar greit chargeis vnto yow quhilk now can noght be helpeit ; bot your lordship most compleit thame, as ye haue done many greater turne.”

It took me awhile to make any sense of all that Hugh’s wife Sara, had written. Olde English when written by Shakespeare and Chaucer is challenging enough for my American head, let alone this complaint of Sara Maxwell in 1632 which I am sure is loaded with transcription errors made long ago. The bottom line: the changes were insufficient; she liked her lifestyle as it was. A faster broadband service wasn’t going to entice her, nor the addition of a Starbucks in town.

On May 25, 1636, Sir Hugh Montgomerie Sr, First Viscount Montgomerie died at the age of 76. His funeral was staged in Newtownard in the Great Ards of County Down, Ireland. Records indicate that the King ordered a royal send off. Hugh was succeeded by his son, Hugh Montgomerie Jr, the Second Viscount Montgomerie (1597-1642). When it is written that an aristocrat was ‘succeeded by’ someone it means that the titles and properties of the departed were assigned to the person identified. The law of primogeniture applied, and the oldest son acquired the domain and all that goes with it including the holiday pass to a waterslide park of his choosing. In the instance that a nobleman died without offspring, the title would pass to his appropriate next of kin, usually his oldest remaining brother or offspring of that brother.

The Second Viscount Montgomery (1597-1642) and Jean Alexander

Father’s 9xGGP, Dunskey Castle and The Great Ards

Hugh Junior married Lady Jean Alexander (1606-1670) in 1623. Jean was the daughter of William Alexander, First Earl of Stirling, Scotland. Hugh and Jean had three sons: 1) Hugh, the 1st Earl of Alexander, 2) James, 3) Henry and a daughter, Elizabeth. As is evident in the death dates of Senior and Junior, the Second Viscount lived only 6 years passed the death of his father. For that reason, not much can be found regarding Junior’s brief stint as the Second Viscount. It didn’t help when the castle in which family records were kept was destroyed by their archrival, the Cunninghams, in a retaliatory gesture that was part of the family feud that endured over the course of four centuries.

In 1637, the Second Viscount Montgomery (Hugh Jr) was made a member of the Privy Council, a powerful body of men who advised the monarch, issued executive orders, and provided a few judicial functions. They controlled the King’s Twitter account.

As ‘The Great Irish Rebellion of 1641’ gained steam, Hugh Jr was appointed Colonel, and played an active role in suppressing the Irish insurrection. As every century in the history of Ireland has been marked by multiple rebellions, it helps to know which rebellion was marked by a clash of Ireland and England (all of them) and which involved economic issues (all of them) and which were results of a clash of religious beliefs (all of them). Well, that was of no help at all.

There are few clashes in our family history that better illustrate the diverse characters found within the various branches of our family tree. While each of many wars pitted cousin against cousin or even brother against brother, the Irish Rebellion of 1641 contains numerous examples of our extended families caught up in the horrific atrocities of bloodshed.

As with his father before him, the Second Viscount Hugh Montgomery was a Scot by birth, but an Ulster Scot by residency. He was quelling a rebellion among the Irish Catholics of the north of Ireland and doing so on behalf of a Catholic leaning King Charles I. Hugh II was protestant and his protestant peers in the highlands were aligned with Oliver Cromwell in the English Civil War, seeking to topple the King for whom the 2nd Viscount was fighting. Among his victims in Northern Ireland were Irish ancestors found in our tree, including my father’s cousins, the FitzGeralds. The atrocities identified in Irish history were committed by both sides of the warring factions, protestant and catholic. The number of victims has ballooned over the years from 5,000 to 200,000 depending on the spin of the storyteller. One thing is clear: the fear, deprivation, and mistrust cultivated by the Rising of 1641 permeates the fabric of present-day Ireland. The good news is that the name of Hugh II is not associated with the carnage among the innocent civilians. He simply killed the other team’s warriors sufficiently enough to claim a victory, crushing first the Irish Catholics and momentarily, the forces of Cromwell.

On the 15th of November in 1642, the Second Viscount died suddenly and was succeeded by his son, Hugh, the Third Viscount Montgomery. This is the ‘Hugh of the Amazing Open Heart,’ to whom I referred in a previous chapter. He held several titles including the Earl of Mount Alexander, nomenclature and lands he acquired via his mother, the Lady Jean Alexander.

Hugh III had a younger brother, James, who was also the son of Hugh II and Jane Alexander. We descend from James.

James Montgomery (1627-1689) and Margaret Fitzwilliam

Father’s 8x Great Grandparents, Dunskey Castle, Wigtownshire

James Montgomery was born at Dunskey Castle, Wigtownshire, on the Scot side of the Irish Sea. Ireland was no more than 13 miles to the west and on a clear day one could see the Irish coastline. James married Margaret Fitzwilliam, the daughter of Col. Fitzwilliam.

James Montgomery dropped the ‘ie’ from Montgomerie and replaced the 2 vowels with a ‘y’. It was a trend started by his father and he continued the spelling. There is little found in the archives related to the life and times of James Montgomery. The shortage of information was, at times, troublesome. Several major volumes, each 500 pages in length (on average) have covered the history of the Montgomery and allied families and have little to offer regarding this James Montgomery.

Present day family internet historians have done great harm to James. I have found him dead and buried on a sandy beach head in North Carolina, lying face down in a swamp in South Carolina, planting tobacco in Virginia, struggling to find a moment of peace in the Great Ards of County Down in Ireland and wailing about the latest injustice in Ayrshire, Scotland. He has died young. He has died old and crippled. He has died at the hands of pirates in the English Channel. He has died intestate (without heirs) and he has died with a healthy brood of children at his bedside in Virginia. He is one of those lovable characters who shows up in any, and every, family tree as a useful tool to get from one branch of a family tree to another. His name is so common among the Montgomery men that he has become a compilation of every James Montgomery found in Great Britain in the 17th Century. As a Steve Smith I can relate to the problem. The fact is, per the meticulous D.B. Montgomery, James never crossed the Atlantic and he did die at the hands of pirates while crossing the English Channel in route to Holland. He did have children who were immigrants in Virginia, including our William and Robert Montgomery.

James, the son of Hugh II offers so little in terms of cool stories that people sometimes elect to erase him and employ James, the son of Hugh, Viscount Montgomery I, as the heir apparent in their family tree. This James was a lusty, stout guzzling warrior, a leader of men, a saber rattling, caber tossing, brawny intellect. This James, son of the First Viscount, Hugh I, destroyed any Irish peasant who stood between James and the quick rents owed him. You get the picture. Who would not want a man like this as a grandfather? There is so little written about James, son of Viscount II, that many writers gloss over him in their family sketches and head toward the table in Barnes and Noble where his brother Hugh III, the 3rd Viscount, can be found signing autographs. And why not write about our Uncle Hugh, III? He has quite a story to tell. So, grab some marshmallows, a chocolate bar and some graham crackers. We will burn some smores at the fire pit and I’ll tell you about this walking Mayo Clinic Miracle, a guy who qualifies as my father’s 8th great uncle.

Great Uncle Hugh III and His Amazing Open Heart

Hugh III, the First Earl of Mount Alexander (1623-1663) was born in Donegal in 1623 to Hugh II and Jean Alexander of Broadstain Beith, Aryshire, Scotland. Their Broadstain lands were found to the west of Glasgow, near the Irish Sea.

The Third Viscount Montgomery was an Irish peer, appointed to command his father’s regiment in 1642. An online bio of Hugh III reveals that he suffered a horrible fall as a child and was severely injured. His chest was pierced open and an extensive abscess formed, which on healing left a large cavity through which one could see his heart beating. He wore a metal plate over the opening for the remainder of his life. I don’t know how he kept that clean, but apparently, he managed. It added new meaning to the term, ‘Holy Heart.’

He was strong enough to travel through France and Italy at age twenty. He was well known by now as a medical phenom, a walking talking window on the heart, a Ripley Believe It or Not character before there ever was a Ripley. On his return home he was brought to Charles I at Oxford, who was curious to see this Montgomery kid and his chest. It is reported that Hugh III spent several days in the king’s court, probably entertaining the royals with his ‘deformity.’

“Could you store a bag of Cheetos in there?” the King would ask, jabbing the metal plate.

It was at this time during the Hugh III 1642 European Tour, that his father Hugh II died in battle at Donegal, a Celtic man suppressing an Irish rebellion and giving his life for King Charles I of England. Hugh III, born in Ireland, then took over in service to the King. Hugh III was appointed to command his deceased father’s regiment in the King’s Royal army.

The rebellions among the clans of Scotland and Ireland were fierce and Montgomery men were sent to suppress the uprisings in the north of Ireland. The rebellions threatened Montgomery property interests in Ulster. Hugh III took command as the Third Viscount at his father’s death and served under Scottish Major-General Robert Monro, who married Hugh’s widowed mother, Jean Alexander Montgomery. Within several decades the Monro family name was found in the heart of Westmoreland County. They settled on Colonial Beach, north of Nomini Bay in the heart of Peter Smith’s neighborhood in Virginia. It was a small world.

Hugh Montgomery III fought at the Battle of Benburb in June of 1646. The king’s troops were defeated, and Viscount Hugh III was captured while leading his cavalry into battle. Rebel forces dispatched Hugh to Clochwater Castle, where he remained thru 1647. He was exchanged for Richard, 2nd Earl of Westmeath. Despite a defeat here and there, Hugh III was successful in his efforts to repress, suppress and redress the Irish. He quickly rose to the title Commander in Chief of the Royalist army in Ulster in 1649. His fortunes were tied to fate of King Charles I.

As Oliver Cromwell and Parliament seized control and decapitated King Charles I, Hugh Montgomery III boldly proclaimed his loyalty to the deceased King’s son, King Charles II. The powerless King Charles II appointed Montgomery as commander-in-chief of the royal army in Ulster on May 14, 1649. He was instructed to cooperate with James, Marquis of Ormonde. Hugh Montgomery III seized Belfast, Antrim, and Carrickfergus. Passing through Coleraine, he laid siege to Londonderry. Within four months Cromwell and his New Model Army forced Montgomery to retreat. Hugh III joined Ormonde in a final, failed effort against Cromwell.

The royal forces of Charles II went down in defeat and surrendered to Cromwell. Cavaliers loyal to the King scattered across the globe, many found their way to the Virginia Commonwealth. Hugh III was banished to Holland and forbidden to consult Charles II. Dunskey Castle and Broadstain, the properties of the Third Viscount Hugh Montgomery, were seized by Cromwell’s Parliament and distributed to John Shaw.

In 1652 Hugh III solicited and received permission to return to London, and after much delay was allowed subsistence living for himself and his family out of his confiscated estates. He was then permitted to return to Ireland, and lived there under strict surveillance, and for a time was imprisoned in Kilkenny Castle.

With the death of Oliver Cromwell in 1658, the British restored King Charles II to power in 1660. The newly appointed king restored his loyal supporter, Hugh Montgomery III, to his properties and anointed him as the Earl of Mount Alexander. Hugh died suddenly and suspiciously at Dromore on September 15, 1663, while investigating Major Blood’s plot. Major Blood was one England’s greatest con artists, thieves and traitors. He staged a great, but failed heist of the King’s jewels from their secured location in the Tower of London. It would have surprised no one if Blood had Hugh III eliminated. It wasn’t proven.

Hugh’s first wife was Lady Mary Moore, eldest sister to Henry Moore, first Earl of Drogheda. The Moore surname appears in the Virginia history of the Montgomery family. Hugh III took for his second wife, Catharine Jones, daughter of Arthur Jones, Viscount Ranelagh Hugh III was buried in the chancel of the church at Newtownards. His son, Hugh IV, born in 1650 was anointed the second Earl of Mount Alexander.

As I take a break here to entertain relatives and dine on a delicious shrimp jambalaya dinner, I would be remiss if I didn’t give a shout out to Henry Paton, author of the biopic Montgomery, Hugh found in SidneyLee’s Dictionary of National Biography. Henry won’t hear me shouting my thanks because the man been deceased for more than a century. Kudos to Thomas Montgomery, D.B. Montgomery and the ancient Montgomery Manuscripts of William Montgomery (1650); all proved helpful in developing a view of the 17th Century Montgomery Clan. I also found Burke’s Extinct and Dormant Peerages to be quite useful (and often boring) in tracing Montgomery lineage from Matilda Montgomery through the centuries to Sir Roger Montgomery in 1066. Of course, I would not have been able to complete any of this task without the support of the Benromach family and the waters of the Chapelton Springs in the Romach Hills of Forres.

Coming to America

Profit making has soared to new heights among various online websites that offer ancestry software and a lumberyard (server) for the avid family genealogist to house the various ancestors they find in their trees. These sites typically include chat rooms and list serves where frustrated researchers can plead for help in locating a great great grandmother they know has to be out there somewhere, just around the corner of the next graveyard in Blueberry Falls, Virginia.

Whenever I find myself bored with the violence and the trash talking offered up on any given NFL Sunday, I boot up one of these ancestry networks and browse through the various pleas for help. The people pleading for help are usually rookies, digging up their first bodies. They are usually willing to trade information in a manner reminiscent of my youth when hawking baseball cards was an art-form. I saw my son exhibit the same skills when Pokemon Cards swamped the marketplace in the late 1990s. The message boards appear to be peaceful sites at first, with wholesome, courteous exchanges by people who mean well.

“Your great great great great great (5x GGA) Aunt Flora may be the Flora found in my tree as a five times cousin, three times removed from my great Uncle Harold! We might be related! OMG! We might be related!” a Rookie may exclaim. “Write me! Come for Christmas!”

But such celebrations are marred by trolls, the same people who snickered in our fourth-grade classroom when we gave a wrong answer in class or asked a ‘stupid’ question in seventh grade pre-algebra. They trolled the substitute teachers of our youth and today they can be found trolling the internet.

“Where’s your documentation?” The troll will ask and include angry emojis. The well-intentioned rookie proceeds to explain: “Grandmother died in a horrific fire that destroyed the family Bible and all records were lost. I am trying to piece together our family history.”

Before the rookie can explain that she is helping her “bed-ridden uncle completes his family tree” the Tree Troll continues in all caps, redressing the rookie’s lack of basic skills:

“WHAT SOURCES R U CITING? You obviously haven’t gone into the Google archives! Wow! You REALLY need to go into the records at the LDS site before you even ask for help in a chat room here at the Wonder-Kin Website. Do some of your own research! “

I witnessed such an attack recently concerning James Montgomery and Margaret FitzWilliam. The exchanges between MirthfulMartha49 and a bevy of helpful, good hearted people was pleasant enough. The chain of posts endured 5 seasons and 55 episodes, much like a Netflix televised serial drama. Martha was earnestly seeking to identify the reasons why William and Robert Montgomery would leave the wealth originally garnered by Hugh, the First Viscount Montgomerie of the Great Ards in 1606 and choose to settle in Virginia in 1666. A person identified as ‘Gravedigger’ interrupted the peaceful procession of probes and info sharing with what amounted to the effort of the neighbor’s dog farting innocently enough in my living room. “Sources?” the troll typed.

Folks ignored Gravedigger at first and continued a dialogue that held promise. All of that was destroyed when Gravedigger followed the innocent enough fart with a cannonade of crap all over the carpet, blasting MirthfulMartha49 for her punctilious probes. Gravedigger reminded me of the sanctimonious prig of a teacher I despised in high school, Ms. Prudence Prance. Prudence would lord over our classroom in her Bonwit Teller fashions in a manner that evoked locker room talk as defined by President Trump. I can hear the rapacious Ms. Prance now as I gobble up a White Castle slider:

“Could someone help Stephen find the answer? He seems to have not read the assignment for today. Or perhaps he is just a tad bit slower than the rest of us. Did you eat your Wheaties this morning, Stephen? Oh, that’s right. You are one of our wrestlers and we all know what that means. Debbie, Please, help Stephen with the question at hand. Why do benzene radicals obliquely enter a dimorphic disposition and state of unrest when exposed to the high carbonate residue of a distillate that would otherwise be tangentially ascorbic?”

Mirthful Martha’s inquiry into William Montgomery’s motivation for coming into the British colonies in the latter half of the 17th Century was intelligent and thought provoking. It was simply too cerebral for Gravedigger and it conflicted with Gravedigger’s mission in life: Find as many ancestors as possible, build a tree, post it and accomplish these two goals:

- Find as many noble men and women (aristocrats) as possible and

- Prove that God invented the world and all my ancestors descend from Sylvester Stallone, Jesus, Moses, Noah, and Adam and Eve; in that order.

I struggled with the question posed by MirthfulMartha49. Why did those who had been wealthy Scot Irish descend into the Shenandoah Valley? We know about the Cavaliers and their desire to escape Cromwell. We know the pilgrims and puritans sought refuge from Archbishop Laud. The poor among the Scot Irish came with hope and a prayer, seeking food on the table and a roof over the head. But what of the grandchildren of the First Viscount Mongomerie? Wasn’t life among the castles of Dunkskey and Broadstain (Ayrshire) and Rosemount (County Down) good enough? Why were they leaving the best golf courses and finest distilleries in the world for the heat and humidity of Virginia? Had it been a bad year for haggis?

Sir James Montgomery of Rosemount, County Down, Ireland, second son of our noted military commander, Hugh the 2nd Viscount Montgomerie, reportedly left Ireland on the approach of Oliver Cromwell and fled for Holland in his schooner. It was on that journey that he was intercepted by pirates and died defending his property. Cromwell had taken photographs of several of the Montgomery boys and their next of kin (McClellans, Shaws, Alexanders and Blairs) and issued writs for their arrest and execution; no trial necessary. He would have posted their images on the internet if dial up had been available. It wasn’t. In fact, photographs weren’t around just yet either. But the writs were real.

All three of the Viscount Montgomery clan (I, II and III) had been loyal servants of King Charles I. They were royalists from start to finish. Even as Cromwell and the Protestant Parliamentarians gained the upper hand during the English Civil War, the Montgomery men were the last to surrender their forces in the Great Ards. Hugh III had been the commander-in-chief of the Royalist army in Ulster in 1649 and seized successively Belfast, Antrim, and Carrickfergus only to eventually surrender to Cromwell as one of the last dominoes to fall to the Parliamentarians. The Third Viscount (Hugh III) was banished to Holland, and not only banished, but directed to never have contact with the heir to the English throne, Charles II, son of Charles I. Charles II sought refuge in Holland. Reports that Hugh III sent Charles II the following quotation from a Rudyard Kipling poem as a comfort card are unfounded:

“If you can keep your head when all about you are losing theirs … Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it.”

I’m messing with you again. Kipling didn’t author the poem for another 160 years. Charles II did keep his head however and a decade later provided Hugh III an opportunity to exit life on an up note. But life went downhill for the Montgomery boys in the decade of the 1650s. The slide began with the 1649 beheading of Charles I. Parliamentarians had no use for Royalist soldiers who had served the nation for decades. Parliamentarians ignored the fact that Montgomery Clan members played a key role, some died, in solidifying England’s control of Ireland. The Parliamentarians seized the opportunity to clean house and rid the nation of men now declared traitors. The issue at hand in 1649 was simply: which Good Olde Boys club is going to rule the islands? Cromwell held the upper hand and the King’s head. The process of ‘cleaning house’ included removing castles and properties from the custody of Loyalists.

Events and details surrounding the deed to Dunskey Castle have perplexed countless students of the Montgomery clan. On June 15 in 1653 “Johne Shaw of Grenocke” was granted Dunskey Castle by Andrew Wardlaw. A deed found in the archives reads:

“Joane Montgrumie alias Mackmath, relict of the deceased Hew Montgrumie the castle, tower and fortalice of Dunskey situate thereupon” to which lands had pertained to Hew Montgomery now Viscount of Airds, and were apprised from him on 1 August 1650 at the instance of Joane Montgrumie alias Mackmath relict of the deceased Hew”

At first blush it appears that the widow (‘relict’) of Hugh Viscount Montgomery II has had the castle and accompanying properties at Dunskey appraised to ascertain a value in 1650. That Joane is referred to as “alias Mackmath” indicates that she either married a Mackmath after the death of her first husband Hugh II or she styled herself as a Mackmath at some point in her life. We know that she was an Alexander at birth. While Jeane (Joane) did marry again after the death of Hugh II, there is no evidence that she married a Mackmath. She did marry Samuel Rutherford, an honored professor of divinity in the University of Saint Andrews and recognized as the greatest theologian of 17th century Great Britain.

With Hugh III banished from the country and his father long since deceased, Hugh’s mother Jeane (Joane) was responsible for managing the family finances. For three generations, the Viscount(s) Montgomery of Ards had been responsible for generating and maintaining a military force responsible to the King of England. When King James I first granted Hugh I the lands of Counties Down and Antrim he also charged him with the need to generate an army and collect taxes. This was the rule of law imposed on titled noblemen.

Hugh, the First Viscount, had done a spectacular job, recruiting families from Portpatrick, Scotland to Down and Antrim. He quickly organized a force of 1000 men. The overhead costs of maintaining troops and the loss to Oliver Cromwell forced the Montgomerys to borrow largely from one agent, cousin John Blair, who foreclosed on a mortgage and became possessed of numerous Montgomery properties including Dunskey. In the summer of 1653, the agency responsible for organizing properties under the rule of Oliver Cromwell then approved the transfer of the property from Blair to John Shaw. Andrew Wardlaw, representing Cromwell, notarized the transfer. It is speculated that Jean Alexander Montgomery had to part with properties to pay down debts accrued.

The Immigrant Ancestor in Virginia

Over a century ago, David (D.B.) Montgomery, informed his audience that,

“James Montgomery of Ireland was the father of three sons who migrated to America in the year 1666 and settled on the James River in Virginia, and whose names were (1) William, (2) Robert and (3) Hugh Montgomery. Of these three brothers, sons of James Montgomery of Ireland, (3) Hugh Montgomery returned to Ireland and died, never having married. Hugh and (2) Robert Montgomery are the names found on deeds granted by Sir Henry Checked and Francis Lord Howard.”

D.B. identified (1) William Montgomery as the father of seven children, three boys and four girls. The boys are named (4) Robert, (5) Hugh and (6) John.

D.B. credits (4) Robert with seven children as well: four boys and three girls. His sons were named (7) William, (8) Hugh, (9) James and (10) Samuel.

Note: William (7), the brother of our (9) James, came into Kentucky by way of the Holston River settlements, aka Wautauga Colony. This William (7) is my father’s 5x Great Uncle. I introduced this William as the 2x Great Grandfather of Mark Twain. William’s adventure in the wilderness of Kentucky is fascinating and is found in the appendix.

Pedigree Chart 19: The Montgomery Family in America 1678-1874

13. Hugh 2nd Viscount Montgomery (1597-1642) m Jean Alexander (9th GGP)

12. James Montgomery (1627-1689) m Margaret FitzWilliam (1625) (8th GGP)

11. William Montgomery (1650) m Isabella Burnet? (7th GGP)

10. Robert Montgomery (1678) m Louise de Saix Crockett (6th GGP)

9. James Montgomery (1695-1756) m Anne Thomson (5th GGP)

8. Hugh Montgomery (1713-1778) m Caroline Anderson (1715-1767) (4th GGP)

7. Samuel Montgomery (1743-1815) m Mary Polly McFarland (1753-1819) (3rd GGP)

6. James Montgomery (1783-1826) m Nancy Cook (1784-1850) (2nd GGP)

5. Matilda Montgomery (1808-1874) m Peter Smith of Posey (1803-1870) (GGP)

4. James Monroe Smith m Jane Stilley (GP)

3. Lebanon Faris Smith m Mary Hughes (JD Parent)

2. James Donald Smith m Doris Christine Weiherman (My Parents)

1. Children of JD and Doris

Pedigree Chart 19 is part of Chart 17 found on page 266 which shows the descent from Sir Roger Montgomery, Earl of Shrewsbury, Shropshire, England.

I have spent considerable time and effort periodically, over the course of years, researching family history in the online records of Scotland, Ireland and colonial America seeking documents (evidence) that support the conclusions drawn by David B. Montgomery. His efforts were thorough. With the advent of DNA testing, his findings will remain subject to conjecture.

D.B. gathered all the literature he could find and traveled the country talking to senior members of his extended family tree. These folks shared memories of past events and previous generations. They catapulted D.B. right back into the early days of the 1800s and late 1700s. The stories could be verified in the Collins History of Kentucky and from there D.B. was able to weave a compilation that gets down right exhausting to read. There is more begetting going on in the beds of our Kentucky ancestors than ever was recorded in the first book of the Bible. And D.B. relates all of it by name and date. I shared two pages of his efforts in his report on the family of Matilda Montgomery and her parents.

In his quest for evidence D.B. sent a letter off to the assay offices and county courthouses in the James River basin of Virginia. He requested a search of records, seeking evidence that would support his supposition that Montgomery families had settled into the basin in the mid-1600s. He struck it rich. Two separate deeds for the purchase of land were found in the record books.

On April 30, 1679 Robert Montgomery and Edward Belson in Nansemond County, VA acquired 850 acres of swamp land. The actual record reads as follows: