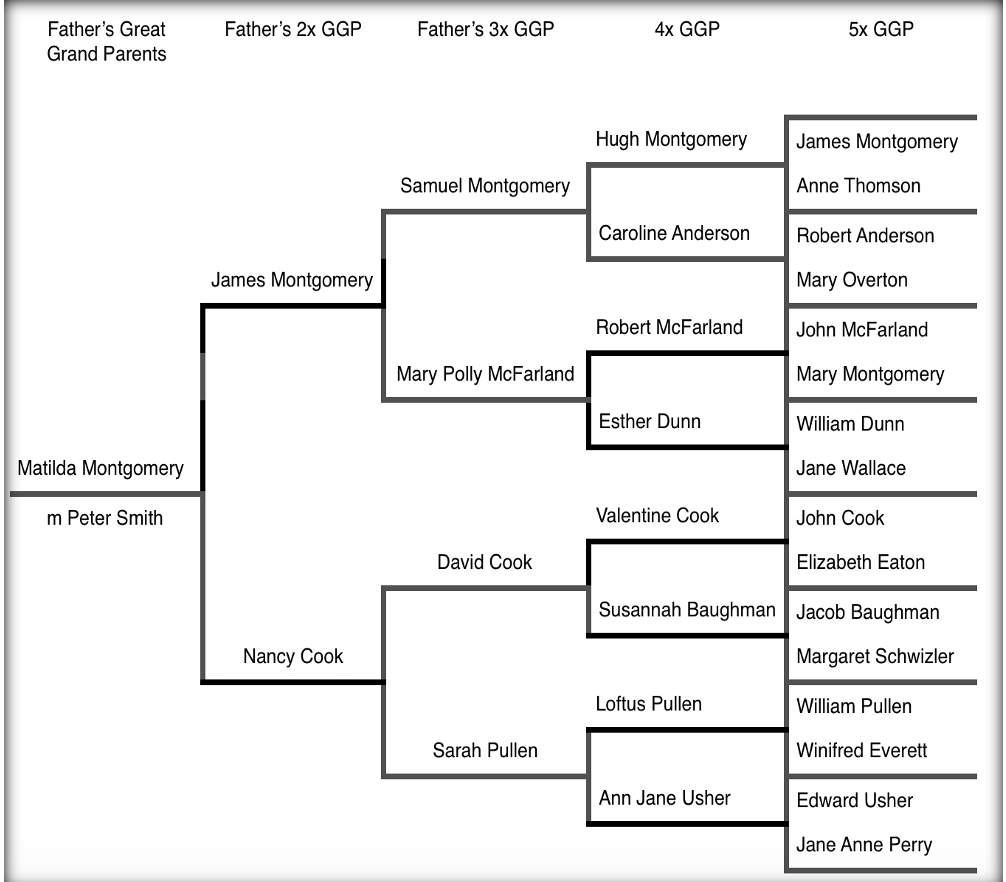

Pedigree Chart 21 spans two centuries. To the right on this chart we have James Montgomery and to the far left, the incomparable Matilda (b 1806). We have met the Montgomery family, the Andersons and Overtons and it is time to move forty miles to the west of Edward Tarr’s blacksmith shop in Staunton, Virginia.

Chart 21: The Scot Irish of the Highlands

The United States government carved the state of West Virginia out of Virginia during the American Civil War. The folks in the area did not view war of any kind as ‘civil’ and thought they had more in common with folks in the Ohio River Valley than the Deep South. Living to the west of the Blue Ridge and ‘Over the Top’ effected the mindset of these pioneers, just as the Piedmont effected Peter Smith of Round Hill, or the pocosin (swampland) impacted William Davis in Hyde County, North Carolina.

Present day Highland County VA borders on the West Virginia state line. The county is decorated from east to west with a series of ridges and valleys that geographers lovingly refer to as the Ridge and Valley System. The ridges run north/south and are rather obvious when flying over the region or staring into a Google Map of the earth.

Highland County is an offshoot of the larger Augusta County, which was carved out of the even larger Orange County, Virginia. As areas grew in population, counties were given birth and local governments established. In 1746 the county surveyor laid out 21 tracts of land in creek bottoms aptly named Cowpasture and Bullpasture. Among the 14 families to first settle into these tracts was a man named Loftus Pullin (1720-1821), my father’s 4th great grandfather.

Loftus was a fourth generation colonial American. His father William Pullen (1690-1767) was a lifelong resident in Lancaster PA and a neighbor to the Slaymakers of the same county. William was the son of Henry Pullen (1660-1698) and Mary Stott. Henry’s father was William Pullen (1632-1690) who was apparently born in Lancaster PA but died in Middlesex VA. This lineage is unique for a pioneer in the Ridge and Valley System in 1746. The Shenandoah Region was settled by many Scot Irish, fleeing the havoc inflicted by British aristocrats who viewed it as their prerogative to squash humanity and subject the downtrodden to even more downtrodden-ness. As an example, the area known as Bullpasture was a real estate development hatched by the Lewis brothers, Andrew and John, formerly of Donegal, Ireland.

Tradition has it that John Lewis was descended from French Huguenot blood on his father’s side and Ulster/Scotch on his maternal side. I introduced him in a previous chapter but didn’t really elaborate on his reason for coming into the colonies. The reason is engraved on his tombstone: He “slew the Irish Lord.” The Lord, Sir Mingo Campbell, illegally raised the rents on leaseholders, forcing the renters to forfeit their leases. The landlords then seized control of the properties and increased profits. Lewis refused to pay the increased rent. Sir Mungo and his posse attempted to evict Lewis by force. Mungo fired a musket shot into the Lewis home and the shot killed Charles Lewis, John’s brother. A second shot wounded Margaret Lynn Lewis, John’s wife. An enraged Lewis charged from the house and promptly split Sir Mungo’s skull with a shillelagh (cane). Lewis also killed the landlord’s steward and with the help of some domestic servants, drove away the remaining posse.

While exonerated, Lewis felt compelled to flee Ireland to avoid the wrath of Sir Mingo’s family and friends and he booked it for Portugal. Within two years, Lewis moved from Portugal to Philadelphia and on to Lancaster, PA. Within another year or two he moved his family, including wife Margaret, four sons and two daughters into the Shenandoah Valley. His history was not atypical, but rather the norm for pissed off Celtic ancestors who hunkered down in the Appalachian Mountains in the mid-18th Century. William Lewis, the son of immigrant John Lewis, married Anne Montgomery, the daughter of James and Anne Montgomery.

Fifteen lots were allocated along the shore of the Bullpasture Creek. For mutual aid and protection, the settlers moved in together. In A History of Highland County, the author identifies the men in Pullen’s neighborhood as Wallace Ashton at Clover Creek, John and Robert Carlisle “in the broad bottom just below,” and Pullen “a mile above in another wide sweep of bottom.” Matthew Harper lived upstream from Pullen. Matthew was of the Thomas Harper family from which my brother-in-law, Charles Cox, descends.

Pullin (1720-1801) arrived in the valley alone, a single man. He lived and died on the shores of the Bullpasture. But he did not die alone. He married the daughter of a young woman whose life story began as a tragic tale in the hills of England. Anne Jane Usher nee Perry, my father’s 5th great grandmother, eloped to America with her lover Edward Usher (5x GGF). She was the daughter of an English nobleman, James Perry (6x GGF) who had not granted permission for the marriage, nor did he approve of her choice for a husband; thus, the elopement. Anne and Edward had four daughters in rapid fire fashion, one died in infancy. Margaret, Anne and Martha grew to adulthood. Edward Usher passed away while the three surviving daughters were quite young.

Usher’s widow Anne returned to England hoping for a reconciliation with her father, James Perry. With her three daughters in tow, she hiked along the dirt road leading to her father’s estate. James Perry recognized his daughter on the road as he drove by in his carriage. He tossed her a shilling and told her that was all she would be getting from him and she ‘must mind her brats herself.’ That’s the story that has been handed down. Anne returned to America with her children and found her way to Augusta County, VA.

In a turn of good fortune, James Knox became a legal guardian of Anne’s daughter, Anne. Back in those days the men of a church or neighborhood would take it upon themselves to provide support for the children of a widow. Meanwhile, back in England, James Perry finally gave up the anger, relented, and gave up his life. His will provided for his daughter Anne and her children. The search to locate Anne Usher nee Perry failed to find her in the backwoods of the Virginia frontier. She never benefitted from her father’s change of heart.

The children of Anne Usher nee Perry grew to adulthood. Her oldest daughter Anne (1733-1804) married Loftus Pullin. Loftus and Anne (Jr) had a daughter Sarah (1765-1810) who married David Cook (1755-1824). David and Sarah had a daughter Nancy (1784-1850) who married James Montgomery (1783-1826). James was the father of Matilda Montgomery (1808-1874), my father’s great grandmother. That would make Loftus and Anne dad’s 4 times great grandparents.

Anne Pullin nee Usher’s sister, Margaret Usher, married a gentleman and scholar, William Steuart, whose travel across the Atlantic was interrupted by Spanish pirates. The crew of the English ship was slaughtered. William, the only passenger on the ship, was set loose on the South Atlantic in nothing more than a rowboat. He survived, but his entire library remained in the hands of the Spanish pirates who were, apparently, avid readers of English literature. Depressed at his loss, Steuart elected to lose himself in the far reaches of the Bullpasture. He became a brother-in-law of Loftus Pullin and a great uncle in my father’s family tree.

James Knox and wife Jean, the legal guardians of Anne Jane Usher, were the parents of General James Knox (1740-1822). An Appalachian legend has it that General Knox began his illustrious career as the jilted suitor of Anne Montgomery, daughter of my father’s 6th great uncle William Montgomery. Unlucky in love and perhaps despondent, Knox became a leader of long hunters, men who trekked into the Ohio River Valley in 1769, especially Kentucky, in search of fur, game and land. He headed up a frontier militia, established a fort and enclave known today as Knoxville and gained fame as a soldier in the American Revolution. He eventually married the widow of General William Logan, Anne Logan nee Montgomery. That is correct. He finally married the woman who had caught his eye as a young man.

William Montgomery had migrated from Lancaster PA to Bullpasture VA. He was the son of Robert Montgomery and Louise de Saix Crockett and brother of Hugh Montgomery (1705-1778), the man who tried to enslave Edward Tarr. William moved into Kentucky in 1779 following the lead of his son-in-law General Logan and William’s daughter Anne (Montgomery) Logan.

William died in his Green River cabin, another victim of a Native attack. His son, John Montgomery, who lived in a nearby cabin was also killed the same night. His son William and daughters Jane and Betsy escaped. It was Jane Montgomery who married General William Casey. General Casey and Ann were Mark Twain’s grandparents.

A Link to the Early Norman and Viking Monarchs

Anne Jane Usher nee Perry descends from a fascinating line of famous surnames that extend back one thousand years. Her father, James Perry, the man who threw a shilling at her feet and left her standing in the roadway with her three daughters, married Ann Swift (1671-1753). Ann Swift was the daughter of Adam Swift and granddaughter of Thomas Swift (1595-1658). Thomas Swift and Elizabeth Dryden had thirteen children. A second son, Jonathan (1640-1667), married Abigail Erick. One of their children, Johnathon Swift (1667-1745) gave the world Gulliver’s Travels and many other literary works littered with Swift’s gift of satire. He was an uncle to Ann Jane Usher nee Perry. Jonathon Swift was her mother’s brother. The author is our first cousin, 7x removed.

Beginning with Ann Swift one can trace the Swift line back 11 generations to Sir Humphrey Swifte in 1330 England. The trail fizzles out there in Durham of Yorkshire. Humphrey’s son, John Swifte of Tinsley (16x GGF- b 1365) married Marie Hedworth (1375-1395) whose brief stint on Earth gave us her child Edmond Swifte (15x GGF) and our link to all of Marie’s ancestors. Marie’s mother was a Darcy, Catherine Darcy (1356-1390). Catherine’s father was the Baron John de Narth de Darcy. The Baron is preceded in his lineage by 8 generations of knighted guys with common names like John, Robert, Phillip, Roger and Thomas. They were all Lords and Barons and their titles provided them with castles and serfs, principally in Lincolnshire.

The Darcy family arrived in England as part of the Norman invasion in 1066. William Nicholas D’Arcy (1010-1086) remained in Normandy. His children began colonizing England. William Darcy was the son of Richard II of Normandy and Richard’s concubine, Papia Envermeu. Richard II had seven sons including William Darcy and Robert I, Duke of Normandy. Robert’s mother was Judith Bretagne. Darcy and Robert I were half-brothers. Robert I married Herleva de Falaise. Among their children was found the irrepressible William the Conqueror.

Richard II of Normandy (963-1026), my father’s 25x great grandfather, descends from a long line of Norman and Viking rulers, too numerous to mention. Among the more interesting characters in this branch of our tree:

Gaange Rolf (846-932) (aia: Robert Ragnvaldsson, aka: Rollo the Great). Rollo was a full-fledged Viking warrior, born and raised in Scandinavia. Norwegians and Danes have a long-standing disagreement as to which can claim him as their iconic hero. He emerged as the outstanding personality among the Norsemen who had secured a permanent foothold on French soil in the valley of the lower Seine. He was the first ruler of Normandy and is found in my father’s tree as his 28th great grandfather.

William I Longsword (893-942) was the son of Rollo and his Christian wife, Poppa de Bayeau. This is a significant moment in Viking lore. Prior to Rollo the Norsemen were viewed as pagan savages. Rollo became a Christian and could now be forgiven for killing people. William carried on that family tradition. But he learned a new lesson: Vikings could be expelled from the Pope’s church if they attacked good old boys in the Pope’s circle of friends. He struggled during his reign as Duke of Normandy with two issues: 1) expansion of his realm into Brittany and 2) maintaining control of rebellions within Normandy and attacks from external forces. He was eventually assassinated by forces loyal to Arnulf I, Count of Flanders. William I Longsword is found in my father’s tree as his 27th great grandfather.

Richard I, the Fearless (932-996) The son of William I Longsword and concubine Sprota was taken hostage by the French King Luis IV in the king’s attempt to regain control of Normandy. Richard escaped at the age of 14 and led a resurgence of Viking control in the region. He introduced feudalism and made all lands within the domain his property. He doled out lands to dukes who managed the properties to which they were assigned or entitled at the discretion of Richard. Found in my father’s tree as his 26th great grandfather.

An online search of any of these names will yield some of each man’s exploits. Trust me; plays and novels have been written about these men and their exploits. To refresh your memory on how we got all these Viking characters into our tree:

Beginning with Matilda Montgomery and her mother, Nancy Cook, I have taken you through six generations of women, great grandmothers whose surname changed on a wedding day.

Matilda Montgomery was the daughter of Nancy Cook, who was the daughter of Sarah Pullen, the daughter of Ann Jane Usher, daughter of Jane Ann Perry, the daughter of Ann Swift. In the year 1671 Ann Swift was born of Adam Swift and Margery Cottrell.

We then passed over ten generations of fathers and sons in the Swift family to find a gentleman by the name of John Swyfte of Tinsley who married Marie Hedworth. The year was 1365 and Marie Hedworth II dropped into life from the womb of Catherine Hedworth nee Darcy. Catherine was the daughter of John II, Baron de Nayth, d’Darcy.

We then ignored eleven generations of Darcy knights and barons and traveled further until we found ourselves in a Norman castle wondering if William Darcy was going to make it to our scheduled tee time at the Greater Normandy Links.

William’s father was Richard II, his grandfather was Richard I the Fearless, his great grandfather was Longsword, the son of Gaange Rolf (Rollo the Great).

In making this journey we have put quite a distance between ourselves and the Smith surname. Each of these characters is, never-the-less part, of our family history, players in a world history that shaped our culture, economic system, government institutions and propensity for alcoholic beverages and foods rich in fats and carbohydrates. As a footnote: If Rollo the Great had eaten right he might not have grown so large that he could not find a horse capable of carrying his weight. Thus, his name: Gaange Rolf, “Walking Rolf.” He literally walked into battle.

The Scottish Highlanders and Covenanters

Among the Scots who fill the Montgomery tree we find the Dunn family lineage. Matilda Montgomery was the granddaughter of Samuel Montgomery (1743-1815). Samuel’s wife was Mary Polly McFarland (1753-1819). Mary Polly was the daughter of Robert McFarland (1730-1788) and Esther Dunn (1730-1794). Esther’s grandfather was a covenanter, David Dunn (1660-1685). David’s brothers, James and Robert, were also covenanters, as was Margaret, their sister. David Dunn is my father’s sixth great grandfather.

The fate of the four family members was captured in a piece titled Notable Men and Women of Ayrshire. The article appears in a collection titled Scottish Notes and Queries, Vol. 4-6.

James Dunn and Robert Dunn: Covenanters, brothers who were martyred at Caldunes, Minnigaff, 1685. b. Glass, Cumnock.

David Dunn: martyred Covenanter, hanged at Cumnock in 1685. b. Cumnock.

Margaret Dunn: martyred in the moors along with Marion Cameron, the sister of the famous leader of the persecuted party. The bodies of the two young women were interred in the moss of Daljig, and more than a century after were discovered in a good state of preservation: shot 1685. b. Glass, Cumnock.

Four members of one family, brothers and sisters, gave up their lives for a cause. This scant information is enough to lead us to a greater understanding of where they lived and why they died. They died because they were Covenanters in 1685 in or near Cumnock, Scotland.

Cumnock is 25 miles to the south of Glasgow in the southwest corner of Scotland. The village of Troon lies 15 miles to the west on the Irish Sea. Troon is a haven for golfers from all over the world. It offers 15 golf courses including the Royal Troon, one of Scotland’s finest. Tucked in the pastoral hills, the villages offer a sense of peace and an opportunity to kick back and relax.

In the 17th Century the people of Scotland and those known to be Covenanters experienced a traumatic upheaval in their lives. The scene was far from pleasant. In fact, the Dunn family died at the hands of the military forces of Kings Charles II and James II in a decade (1680-1688) known as the ‘Killing Time’. Covenanters were Scottish Presbyterians who wished to worship God in their own manner. The movement began in the 16th Century (1500s) with the establishment of the Presbyterian Church in Scotland. Followers of John Knox made a Covenant with God and with each other that bound them to principles found in the Covenant that the Israelites made with God as described in the Old Testament. They distanced themselves from the Church of England which they viewed as an extension of the English Monarch and a tool of oppression.

They resisted the Anglican Church and with the rise of Charles I as king in the 1630s they feared that Catholicism would once again rule Scotland. They sent militias into Catholic Ireland to protect Scot migrants who were oppressed by the Catholics. They would have none of that. They made that point well known over the course of the 17th Century. They took up arms, waged war and died for their cause. In the English Civil War of the 1640s they helped Parliamentarians defeat the Royalists of King Charles I. They were then trashed by the very Parliamentarian forces of Oliver Cromwell they had helped.

They were pissed and very defiant in their outlook on life. They continued to stay the course of their 16th Century founders and contributed to the unrest and civil wars that inflamed the island kingdoms. The turmoil and resistance were greatest in the southwest of Scotland where an offshoot of the Covenanters, the Cameronians, expressed open hostility toward King Charles II and his successor James II. Led by Richard Cameron the underground movement swelled with supporters and burst openly onto the scene as a force to be reckoned with when they routed the King’s militia at Drumclog. They were a ragtag army of angry Scots armed with little more than farm implements and kitchen utensils (pitchforks and knives).

Emboldened by their beliefs and recent victory, twenty armed men stood in the Sanqhuar village commons in support of Michael Cameron, Richard’s brother, as he delivered the Sanqhuar Declaration in 1680. The speech basically declared war on King Charles II. For the second time in the 17th Century a Scottish uprising blew up in the king’s face and resulted in his removal from office. The first uprising occurred at St Gilles church in 1638 when Jenny Geddes threw her ‘chair’ at the Archbishop during his sermon. Jenny’s ‘chair’ was the match that started the fires of the English Civil War and resulted in the beheading of Charles I.

The energy backing the Camerons could hardly be contained and southeastern Scotland became a hotbed of revolution. For ten years, King James was determined to suppress the damn belligerents who had succeeded in separating their region from the King’s control. The king sent in his most ruthless force of 6,000 Scottish Highland infantrymen to quell the rebellion. It was not the first time that Scots had been sent up against Scots by English monarchs. We saw this with Robert the Bruce and William Wallace. We saw it again in the 1640s as Parliamentarian armies of Scotland fought against Royalist forces of Scottish soldiers.

The Highland force was barbarous in its’ approach to containing the unruly Covenanters of the Lowlands. The King supported their efforts and frustrated by years of unrest, finally authorized the killing of any Scottish hostage suspected of treasonous acts, including failure to avow allegiance to the monarch. Highland soldiers could lawfully haul a suspect into a field and dismiss them with a shot to the head without a trial. The Dunns were victims of such an atrocity.

James and Robert died according to their brief obit as martyrs in the village of Minnigaff, twenty miles to the south of their birthplace in Cumnock. David died on the gallows at Dumnock. His sister, Margaret Dunn, was apprehended with Marion Cameron, sister of rebel leader Richard Cameron, and the two ladies were exterminated in a bog at Daljig. Marion’s brother, Richard Cameron, had been tracked down and executed five years earlier in 1680, shortly after issuing the Saqhuer Declaration.

It was no wonder that the children of such tragedies would seek to escape to America and start life with a greater hope for living in accord with their beliefs. And so it was that the offspring of James, Robert and David Dunn arrived on our east coast, finding their way into the Appalachian back country. A person who had survived the brutality of the Highland militia had little to fear living among the Natives of America.

It does cause me to ponder our present situation in this very same nation today. Here, in 2018, we have turned our backs on the victims of oppression and warfare in Central America. We have closed our doors to the immigrants who come to us as our ancestors once came, seeking a safe place to sleep and raise a child.

David Dunn’s son William (1685-1732) married Jane Wallace (1686-1732) and their daughter Esther (1730-1793) married Robert McFarland 1730-1788). Robert and Esther are my father’s fourth times great grandparents.

The Cook Family

Matilda Montgomery was the daughter of James Montgomery (1783-1826) and Nancy Cook (1784-1850). The Montgomerys lived in Gibson County, in southern Indiana. James and Nancy were each born in Kentucky and migrated north, crossing the Ohio River and settling in just north of the river a few miles.

Nancy was the daughter of David Cook (1755-1824) and Sarah Pullen (1765-1810). We met Sarah earlier as the daughter of Loftus Pullen and Ann Jane Usher. David Cook is the guy I now want to position under the spotlight. He was born in Pennsylvania at an early age and moved westward into Kentucky from Virginia at a later date. David’s parents were Mennonites, Valentine Cook (1730-1798) and Susannah Baughman (1732-1807).

The keywords “David Cook 1755” yield one historical clue to David’s crowning moment in life: He wanted desperately to kill a man. Had he done so, the courts would have found him innocent and rewarded him with honor. That, at least, is how the legend goes in the annals of history written in the 19th Century.

Here is how his story unfolds. In 1781 David acquired 115 acres of land on the Dix River, five miles from present day Stanford in Lincoln County KY. His homestead stood near what was referred to in history as the Preachersville Turnpike. The land was granted by the then Governor of Virginia, Benjamin Harrison. He worked at times in the company of Daniel Boone and William Bailey Smith.

On March 22, 1782 David Cook stood beside Captain James Estill on Hinkston Creek in Montgomery County, Kentucky, in a battle that became known as “Estill’s Defeat.” A party of 25 Wyandottes had been marauding about the countryside in the latter days of the American Revolution.

As the Wyandotte gazed into the future, they could foresee a time when they would lose their hunting ground in the Ohio River Valley. The war between Britain and the colonists offered the Natives a last chance to rectify the situation and attempt to remove the European settlers from their wilderness. Surprise attacks on pioneer enclaves, individual families in isolated locations, murder and mayhem were all part of the calculated effort to spread fear, consternation and a retreat by the white guys coming into their native lands.

An attack on the home of Captain Innes and the scalping of an Innes daughter, precipitated a quick response from an early version of the First Responders. Captain James Estill and a party of 25 gave an immediate pursuit and tracked the Wyandottes to the banks of Hinkston Creek. Estill caught the Natives by surprise as they were preparing to barbecue a bear kill. Estill’s men fired the first shots. The Natives quickly took shelter amongst the trees and retuned fire. Both sides lost. No one really won. The white guys lost seven dead, several wounded. The Natives lost 17 but were able to claim a victory as Estill was killed and his men routed from the field.

David Cook suffered severe wounds but survived. He and others among the unit testified that Estill’s death and the “defeat” was due to the cowardice of one man, Lieutenant Miller. Conflicting stories indicate Miller failed to carry out orders given to him and fled the scene in terror, ordering 6 men under his command to retreat with him. The Native chief, sensing less fire from the enemy and a chance to attack, did so. It was at that time that Estill suffered his fatal wound and that Cook was badly wounded.

Several historians note:

“David Cook watched patiently for twenty years for William Miller, swearing he would kill him on sight, but Miller prudently kept away. If he had met the threatened state, no jury in Madison County would have convicted him. So intense was, and to this day is, the admiration for those who fought, and the detestation for those who shamefully retreated from, that most desperate of all frontier battles.”

David Cook sold his homestead in Lincoln County, KY to his brother John and moved west into Missouri with Daniel Boone and others seeking to remain on the front edge of the westward movement. He died there in 1824. He had lived another 41 years after the battle which took the life of James Estill. Cook and his wife, Sarah Pullen had ten children born between the years 1779 and 1795. Nancy Cook (1784-1850) married James Montgomery and they are my father’s second great grandparents.

Again, I must point out the Small World concept that plays itself out in the migration of east coast colonists and now Ohio Valley pioneers. Just as the Wyandottes traveled in bands, our early European ancestors traveled in pack formation, like mother elephants protecting their young and supporting one another. David Cook’s journey in life took him from Lancaster Pennsylvania to Borden’s Patent on the Bullpasture in the Shenandoah to the hills of Lincoln County, Kentucky. William Miller, the man who betrayed Estill and David Cook, had traveled the same migration route as David Cook. Their families were intertwined in Pennsylvania and western Virginia. Miller have violated the trust these pioneer families held so dear. He was shunned onto his death.

Valentine Cook (1730-1798) and Susannah Baughman (1732-1807)

David Cook’s father Valentine Cook was born in Yorkshire, England. Valentine was the son of John Hamilton Cook and Elizabeth Eaton. Early family narratives agree that John Hamilton Cook was a first cousin of the mariner and world explorer, Captain James Cook whose exploration of the Pacific Ocean resulted in the European discovery of New Zealand and Australia. Finding Australia where it was, located at the end of the Earth, gave Britons great joy.

“Now we have a perfect location for all these horrible criminals and snotty nosed brats!” rejoiced the men of Parliament.

John Hamilton Cook family moved from Marton-on-Cleveland in Yorkshire to London. He passed away in 1736 when son Valentine was only six years old. Within the year the widow Elizabeth married William Sly and the newlyweds and children moved to Amsterdam, Holland. It was Valentine’s first encounter with bumper stickers and t-shirts that boasted, “If you’re not Dutch, you’re not much!”

Valentine and his older brother Jacob moved to York, Pennsylvania while still young men. He married a Swiss immigrant, Susannah Baughman in 1751. At some point in 1754 he helped his brother-in-law, Henry Baughman, construct a palisade fort on land on Greenbrier Creeknear near present day Alderson, West Virginia. This was the year in which Native insurrection was in evidence in the valleys of the Shenandoah and its’ tributaries. James Montgomery and his family had taken shelter at a fort in Brandon VA where he and his family survived the first wave of attacks. In 1755 Henry Baughman was killed in a massacre at his fort.

The children of Valentine and Susannah Cook were born between the years 1755 and 1770. The records of the Mennonite Church (1763) indicate the couple had eight sons: Adam, Jacob, David, William, Henry, John, Valentine, Alexander, and one daughter, Christiana.

In 1764 Valentine is living on a 170-acre tract of land on Hawsksvill Creek. It is while living on the Hawksbill that his sons Valentine Jr (the famous preacher), William and Henry are born.

In 1773 the Cooks moved again. With each move Valentine was able to increase the acreage he owned, but an increase in land mass does not necessarily connote success or guarantee survival in the forest. With this purchase he acquired 650 acres on Indian Creek. Members of his wife’s Baughman family purchased 287 acres nearby.

Documents indicate a few incidental activities in Valentine’s life:

- His neighbor, James Burnside, sued him in a Botetourt County Court.

- He sold wolf pelts and brought home $1.40 in Virginia coin.

- He went shopping at Matthew’s Trading Post and bought various “sundries.”

If future family, three centuries from now, find evidence that Steve Smith went to Walmart and bought a few things, or shopped Home Depot and found the sump pump he needed to drain a wet basement, I suspect the reader will say something like, “Who really gives a rat’s ass?”

What makes the entry regarding Matthew’s Trading Post interesting, is that we seldom find these bits of information in the archives. We do find inventories of stuff that accumulated in the lives of pioneers. Those items are usually itemized after one’s death and indicate an attempt was made to divide the “wealth” or pay off debts left by the deceased. The purchases that are most often mentioned are land and slaves. To know that Valentine got up one morning, ate breakfast, got on his horse and road down the dirt road to Matthew’s Trading Post is a snippet of pioneer life I don’t really need. I have already given it too much time in this story. Tell me he was attacked on the way by a warrior, a pack of wolves or an angry woman who despised his last sermon. That would be a story worth sharing.

At least the Hughes family in our tree got it right. Edward Hughes went 20 miles one way in a blizzard to purchase medicine at a Chicago pharmacy to save his children from certain death. Now that’s the kind of shopping trip I want to hear about. Or Bernard Banks who went off in his wagon, also caught in a blizzard, and died beneath his wagon, stuffed as best he could inside the guts of his horse. That’s a notable shopping trip.

In that same year, 1774, the Cooks and neighbors build Cook’s Fort on Indian Creek and they are going to need it. The American Revolutionary War was underway, and the Natives along the Appalachian Ridge were joined with British troops in disparate attempts to unseat the pioneers and send them running back to the Atlantic coast. Valentine and his son David, now a 19-year-old man, fought side by side at Point Pleasant in Dunmore’s War. Though a peace-loving Mennonite, Valentine’s priority was survival and protecting his family.

Under the command of Andrew Lewis, the Virginia militia pushed Chief Cornstalk and the Shawnee further west into the Ohio River Valley. Cornstalk was pursued and hunted down and forced to sign a treaty, putting a temporary end to the hostilities. Three years later, in 1778, the Natives raided Cook’s Fort and Donnaly’s Fort, continuing the pattern of confrontations that began with the arrival of the first white guys in the New World.

It appears Valentine may have sold most of his acreage in 1775 but maintained frontage property on Indian Creek. He built and operated the first mill in the area. It was in the year 1782 that David and his brother John Cook packed up the horses and headed west, with their Baughman cousins, into Lincoln County in the Kentucky wilderness. A year later David’s sister Christina and her husband moved to Fayette County KY.

This is what the migration pattern looked like: first one or two members of the family with cousins and friends, and a year later another wagon load of in laws and neighbors traipsing down a dirt bath wishing someone would invent airplanes and a Motel 6. A Cracker Barrell would be nice.

In 1783 Valentine opens an ordinary (tavern) on his mill property and why not? If grinding grain for a living is providing the commodity that makes for a popular aperitif, then fire up the still and open a tavern. The Cooks were in the business of selling “spiritous liqueurs.”

A few more details emerge from the available archives. The Cooks purchased more land in their later years. At his death in 1797, Valentine owned 1050 acres. His will, found in the Greenbrier (now Monroe) County Will Book, doled out the land in thirds with his wife, Jacob and Valentine each getting an equal share. Wife Susannah also got the house and all furniture within, referred to as “moveables.” She also maintained ownership of two slaves, Hannah and Ben.

Valentine’s Will also mentioned his gristmill and power mill. He authorized the sale of the grist mill and dictated that the proceeds from the sale of said mule should be divided among his remaining children. It is believed that Jacob ended up with the mill and carried the ownership forward in the family. Today the mill is an historical park preserved by local history buffs and open to the public.

We have met my father’s third great grandfather David Cook, Valentines’s first born child. I have David Cook’s brother, Valentine Jr, sitting on our deck pontificating about God, Jesus and salvation. He has asked if he can come into this story. I have debated the need to include him, but he began quoting scripture and threatened me with an eternity in hell if I didn’t at least make mention of his life’s work. I relented. He is a great uncle, after all.

Valentine Cook Jr (1769-1821)

Father’s 3rd Great Uncle

The Reverend Valentine Cook was a traveling roadshow, one of the forerunners of today’s Television Evangelists. An itinerant Methodist preacher, Valentine gained fame for his knock him dead style and grip on the meaning of anything found in the Bible. For ten years (1788-1798) he worked the east coast, traveling through Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania and western New York. This was back in the day before the RV and Airstream trailers.

Cook’s conversion from Mennonite to Methodist was hardly acceptable to his father, Valentine Sr. It caused a bit of a stir in the house according to biographers of the preacher’s life. But his commitment to Bethany Bible College, ordainment as a minister in the Methodist Church and desire to travel great distances to share the faith, convinced his father that the son was as dedicated a Christian as any Mennonite dad had ever known. The Church counted on Cook to preach as he traveled through his territories, riding a circuit that would include at least two states in the newly formed nation, the United States of America. Wherever he was able to convert enough folks to the Methodist faith, the church would then provide preachers who would tend to a congregation and construct a place of worship. He was acclaimed as one of the great orators of his time. Preachers of other faiths acknowledged that he moved them emotionally to heights they never thought possible. At the same time, he was praised by Biblical scholars for his depth of knowledge and accuracy with regards to Biblical history.

In 1800 Cook was the driving force and lead presenter at the nation’s first ever Camp Revival. Camp Revivals took on new meaning in the 21st Century. In today’s marketplace the wannabe Rock Stars for Jesus rent large football stadiums or indoor arenas, publicize the upcoming events using all forms of media to hype the evening or weekend and often enlist the aid of several celebrities as vocalists to inspire the audience. Men like Billy Sunday in the mid-20th Century and Billy Graham in the latter half of the same century were famous for their ability to ‘bring people to Jesus’, ‘save souls’ and ‘share God’s love.’ The marketplace boomed with TV evangelists and Crystal Palaces with 20,000 members donating large sums of money to do God’s work.

Valentine Cook was the forerunner of the movement two centuries ago. Folks gathered from miles around on foot, on horseback, in family wagons, to hear the man talk of God and Jesus. The church would provide a clearing in the woods and spread the word of the coming event. People camped out, anticipating the glory and excitement about to unfold. It was a bit like Woodstock without Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin and all the sex and drugs. The high came from the Holy Spirit and the rock and roll was on the ground as one writhed in ecstasy filled with God’s love.

In 1799 he was called by the church to serve as President of the Bethel Seminary and he settled into a home in Harrodsburg KY. It was apparently hard for him to hold down a desk job when he was programmed to preach from a makeshift pulpit in the woods. He couldn’t sit still for very long. Cook was determined to end his life’s work as he had begun. Following his wife’s death in 1807, he got back on his horse and road through the towns and villages of Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania preaching to the grandchildren of his earliest audiences for what would amount to his ‘Final Salvation Tour’.

The man was not without his failings. Those who wrote books about him loved to include stories about his “peculiarities and eccentricities.” His mind could be so absorbed in a thought that he could totally forget everything else and any one of value in his life. He was, wrote several authors, so absent minded that he would ride his horse a distance to deliver a sermon at church and then walk home leaving his horse tied up outside the church. Imagine the scene:

“Where’s your horse dear?” his wife would ask.

“Say what?”

“Uh dad? Didn’t you ride Old Dusty to church this morning?” a child asks.

“Say what?”

“Where’s Dusty, dad?” a second youngster wails uncontrollably.

“Oh, I don’t know.” Valentine wandered off into a corner of his mind.

It is easy to picture the scene. We have all had our moments. He did this same thing with his new bride. She went to church with him in his buggy and he left her there as he drove the miles home to her father’s house. Coming into the in-law’s home for Sunday lunch without their daughter was a bit embarrassing I am sure.

“Where’s your wife dear Valentine?” the mother-in-law would ask.

“Say what?”

“Our daughter, your wife? Where is she?”

“Uh dad? Didn’t you ride with mom to church this morning?”

“Say what?”

“Dad! Where’s my mother?” A sceond child would shout.

“Oh, I don’t know.” Valentine wanders off stage left with Nueske bacon in hand.

I despise TV evangelists and “men of god” like Kenneth Copeland, Jesse Duplantis, and Joel Osteen who take hundreds of millions of dollars from their far poorer audience and build 30,000 square foot mansions and ride in one of several of their stable of tax-free jets. I am drawn to this bumbling, brilliant man, Valentine Cook Jr, so eager to put in long miles of weary travel in his passion for work. He was my father’s 3rd great uncle, the brother of dad’s 3x GGF David Cook.

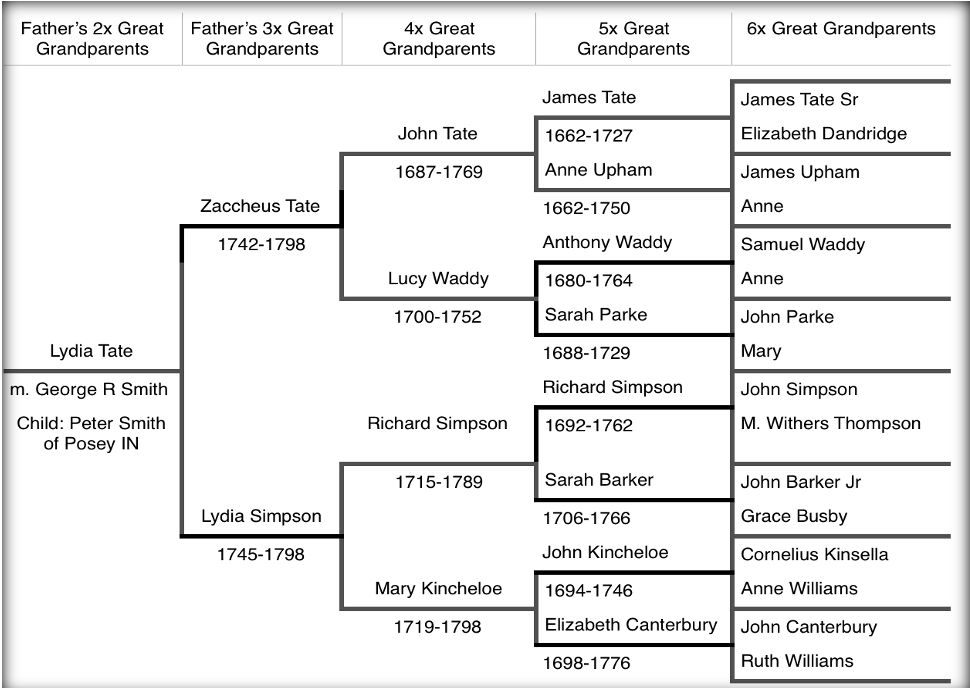

The Allied Families of Lydia Jenny Tate

We have completed a massive search and rescue job in the Montgomery branch of my father’s family tree. It began with the shred of information revealing Matilda Montgomery as one of my father’s great grandmothers and wife of Peter Smith of Posey, Indiana. Peter’s father was George Rudolphus Smith, born in Round Hill NC of Peter Smith. I introduced George earlier and after the intro he tottered off to his still and created another fine whiskey, I am sure. It is not George I care to discuss, but his wife Lydia Jenny Tate, one of my father’s great great grandmothers (2x Great).

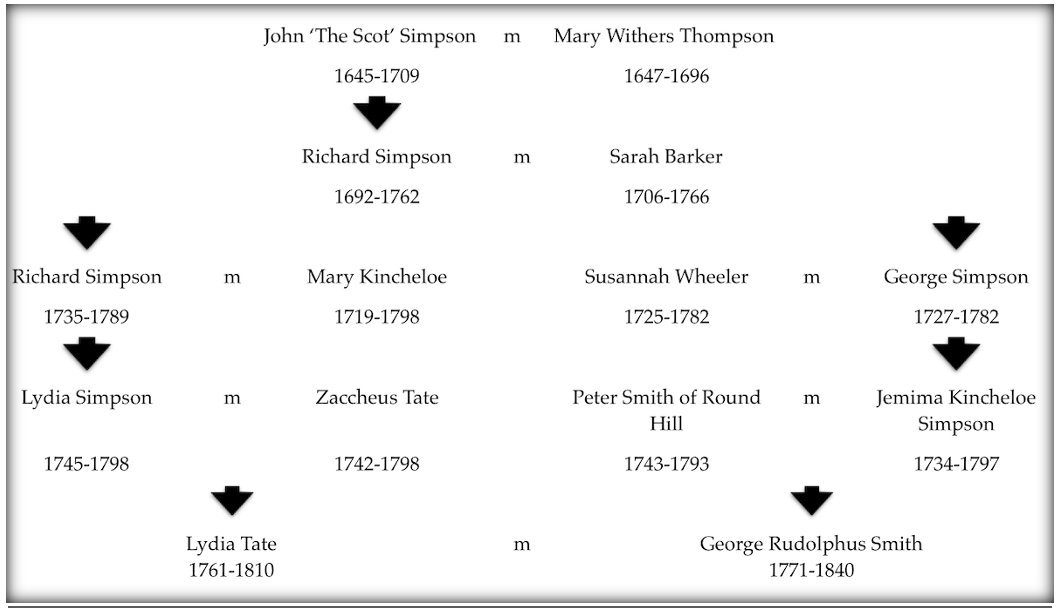

Pedigree Chart 22: The Allied Families of Lydia Tate

Lydia descended from the kings of both Ireland and Norway and was probably oblivious to that fact, living and dying as she did in the hills of Carolina and Kentucky.

Until recently, little was known of George Rudolphus Smith outside of Posey County, Indiana. The Smiths of Southern Indiana were well connected and actively involved in community life but knew little of their origin in 17th Century Virginia. Pearl Smith, a 20th Century Smith family genealogist gathered and published a significant amount of research related to her Smith lineage. An elderly woman in Posey County seeking the ancestors of George R. Smith, contacted Pearl and shared her family’s history. Pearl recognized the migration pattern from Round Hill NC and Muhlenburg County and helped connect the folks in Posey with Peter of Yecomico in Westmoreland County. Pearl’s efforts provided many of us with a sense of our colonial history.

Even less was known of George’s first wife, Lydia Jenny Tate. Lydia died while George still resided in Kentucky. He arrived in Indiana as a single man and eventually met and married Sarah Armstrong. The Armstrong family was not new to George. They had also lived as George’s neighbors in Muhlenburg County KY or Caswell County NC. This is evidenced by the fact that George’s brothers: 1) John Bailey Smith, married Sarah’s sister, Elizabeth Armstrong. And 2) James Smith married Peggy Armstrong. James and John Bailey Smith both died in Paradise and did not make the journey to Indiana. My father descended from the union of Lydia Jenny Tate and George. Lydia descended from a hearty line of Scot Irish blood.

I can Google any one of the names on this chart and find entries related to their life on Earth and probably a few stories about their days in Hell. Life wasn’t always easy. These families moved in mass from Westmoreland Co. to Prince William County VA and into Kentucky. Their recorded deeds reveal frequently adjacent lands. They appear as witnesses on behalf of one another in deeds, Last Wills, marriages and court proceedings. And oh yes, they do intermarry, and often.

Lydia Jenny Tate was the child of Lydia Simpson (1745-1798), daughter of Richard and Mary Kincheloe Simpson and Zaccheus Tate (1742-1798) son of John Tate (1687-1769) and Lucy Waddy (1700-1752). Zaccheus is my father’s third great grandfather. Zak had six brothers and 3 sisters. When his mother Lucy died, Zak’s father, John Tate, married a second wife, Mary Waddy, the cousin of Lucy Waddy. Mary Waddy and John Tate had one son, Zedikiah. John Tate was notorious for giving his sons names that began with the letter ‘Z”: Zacharias, Zaccheus, Zenas, Zephaniah and half bro, Zedikiah. Zaccheus Tate and Lydia Simpson followed the example set by father John Tate: the couple had 8 boys and 5 girls including three sons named Zaccheus, Zeus and Zephaniah. Apparently, the Hispanic name Zorro had not yet caught on in Anglo America.

Zak and Lydia’s daughter, Lydia Jenny Tate (1761-1810) was born in Orange (Caswell) County NC and died in Muhlenburg KY. That she wasn’t named Zelda is inexplicable. She was the wife of our George Rudolphus Smith and mother of three of his many children. Lydia Jenny Tate’s three children included our Peter Smith of Posey, Zaccharias and a daughter named Lydia. The three children would grow old together on or near the homestead and distillery of their father, George R. Smith in Posey, Indiana and George’s second wife, Sarah Armstrong.

After his wife Lydia passed away in Muhlenburg, George married Sarah Armstrong and he fathered another 8 children. Sarah was a well-loved step grandmother in our tree. She was a rock in the foundation of the family as it established roots in the what was the far west of America at that time. We met both George Rudolphus Smith and Sarah Armstrong in previous chapters.

Tate ancestors moved with the Smith line from coastal Virginia to Caswell NC, and into Kentucky. While Peter Smith and son James were making a living in Westmoreland and Prince William Counties, the Tates were flourishing in New Kent County.

The colonial Tate families descend from James Tate (1615-1665) in Newcastle, England. British records reveal his baptism on September 1, 1615 in Newcastle on Tyne. His father was identified as William Tate. The records do not provide a mother’s name. I find that to be true quite often, lending credence to the notion that 17th Century British men were chauvinistic bastards all hung up on their white male privilege. Some attached the first name of Katherine to the woman who gave birth to our James, but I see no reason why it shouldn’t be Zelda. Let’s get the letter ‘Z’ started early on here in the Tate family. James Tate arrived in Virginia in 1652, fleeing the rule of Cromwell, having crossed the Atlantic, seeking peace. By banding together with likeminded friends and relatives he sought prosperity and a new life. James married Mary Evans and they started a family.

The Tates were members of St. Peter’s Church of New Kent, VA. Established in 1679 the church is the oldest parish church in the Diocese of Virginia and the third oldest in the Commonwealth. The church congregation remains active and vibrant.

The Tates were members of St. Peter’s Church of New Kent, VA. Established in 1679 the church is the oldest parish church in the Diocese of Virginia and the third oldest in the Commonwealth. The church congregation remains active and vibrant.

Martha Dandridge, who would later become the wife of Col. George Washington, was born at Chestnut Grove in 1731 and attended St. Peter’s. She married Col. Daniel Parke Custis, a member of the vestry and former churchwarden in June 1749. Her father, Major John Dandridge, also served as churchwarden and vestryman of St. Peter’s. Her great-grandfather had been the first rector of nearby Bruton Parish. After eight years of marriage Martha was widowed with two surviving children. On January 6, 1759 the Rector of St Peter’s Parish, the Rev’d Mr. David Mossom, conducted the vows in the marriage of Col. George Washington and the Widow Custis.

The church records are well preserved and date back to the 17th Century. Scrolling through the registry I found the birth of “Mary Tate daut of James Tate baptiz. the 20 Aprill, 1694.” No mention of mother. Seventy-five years and one generation after William Tate had been identified as the father of James in a Newcastle baptism, and an ocean removed from England there is still no mention of a child’s mother in the church records. Imagine if Christianity had forgotten the Mother Mary and cast her aside in the Bible with the simple notation: “Jesus son of Joseph, Bethlehem, Witnesses: 3 Kings.”

Clearly the father of Ann and Mary, “James Tate,” is not the same James of Newcastle, born in England in 1615. What we have here is the son of James of Newcastle and Mary Evans. On a second fishing trip into the St. Peters Registry I found the baptism of “Ann Tate, daut of James in 1689.” The Registry reveals the structure of the first of the Tate family born and raised in the same church as the nation’s first, First Lady Martha Washington.

This James II, father of Mary and Ann, was born in 1638 and married Elizabeth Dandridge, a daughter of John Dandridge. They had 6 children including James Tate III (1662-1727) who married Anne Upham (1662-1750). Each generation of Tates continued living in New Kent VA.

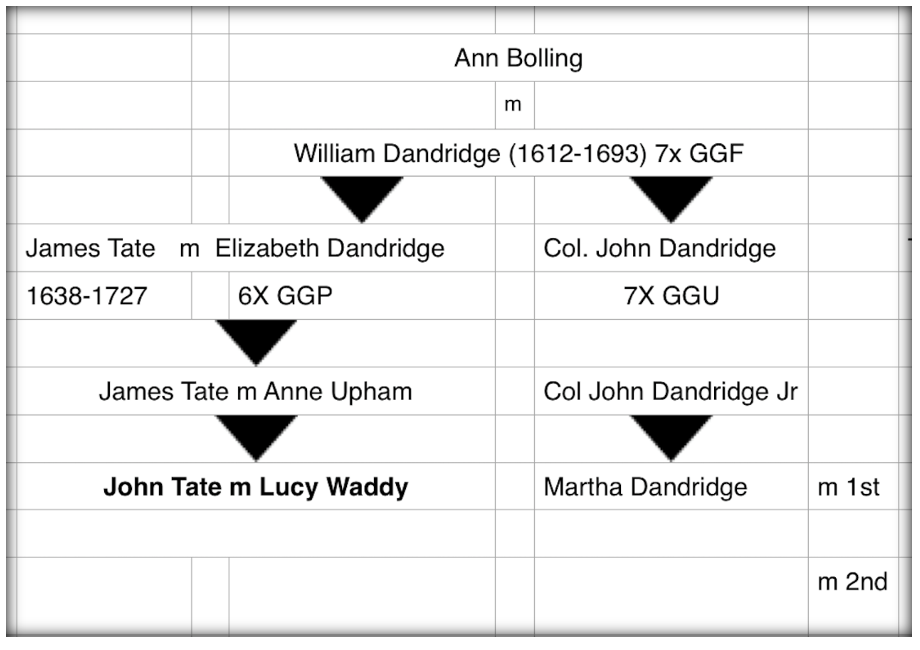

A Family Connection to President George Washington

There is no one in the world who can claim to be descended from President George Washington and his wife Martha Dandridge Custis Washington. Martha brought two children from her first marriage into her marriage with George, but George never fathered a child. My father could claim, as could anyone who descends from my father, a close connection to Martha Dandridge Parke-Custis Washington. My father’s 7 times great grandparents, William Dandridge and Ann Bolling, were Martha’s great grandparents. Dad and Martha descend from the same folks, William and Ann Dandrige. Will and Ann Dandridge had several children including Elizabeth and John Dandridge. Elizabeth married James Tate (1638-1727). Liz and James Tate were my father’s 6x great grandparents.

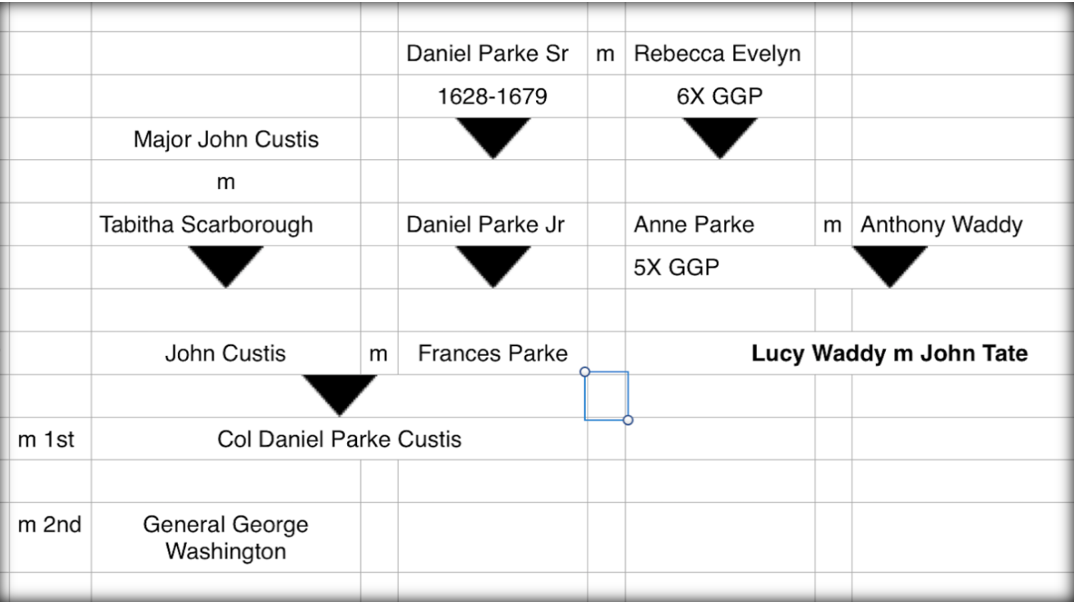

Pedigree Chart 23: Martha Washington’s Link to my Father

William and Ann Dandridge also had a son, Col John Dandridge who was my father’s 7th great uncle. He fathered a few children, including Colonel John Dandridge Junior who was my father’s first cousin. Willliam Junior’s daughter Martha Dandridge, my father’s second cousin, had two husbands in her lifetime: 1) Colonel Daniel Parke Custis, by whom she had two children and husband 2) General George Washington, First President of the United States of America. Again, George and Martha did not have any children of their own. George loved Martha’s children as his own or so the story goes.

It will take another pedigree chart to help make this a bit clearer. I hope the next charts help. If not, take two aspirins and call me in the morning. On second thought, don’t call. I’ll be sleeping.

* * * * *

Well, I failed to slip Pedigree Chart 24 into the space remaining on this page. It looks like we are going to have space left vacant here. If you are interested in posting an advertisment in this space please advise us immediately via Email, or like us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Tender, Farmers Only.com or any of our other social networking sites. Preference will be given to Wisconsin based companies dealing in dairy products, beer, bratwurst or bacon or any other product that induces weight gain, high cholesterol, trigylcerides or creates a tendency to eat pickled brussel sprouts, stinky cheese, smelt or a delirious consumption of brandy old fashions.

Pedigree Chart 24: Martha Washington’s First Husband’s Link to my Father

Beginning with Chart 23: Notice that to the right of Martha Dandridge I have inserted ‘m 1st’ and below that ‘m 2nd.’ That means married first and then married second. Go to Chart 24 and you will see the same notation in the first column, bottom left.

Martha Dandridge Washington’s first husband, Colonel Daniel Parke Custis, was the son of John Custis and wife Frances Parke. Her grandfather was Daniel Parke Sr. My father also descends from Daniel Parke Sr (1628-1679) and his wife Rebecca Evelyn. They are my father’s 6th Great Grandparents. Their daughter Ann and Anne’s husband Anthony Waddy are father’s fifth great grandparents.

Martha’s first husband Colonel Daniel Parke Custis descends, not from Anne Parke, but her brother Daniel Parke Junior. Daniel Parke Sr was a great grandparent of Martha’s first husband Colonel ‘DPC’.

Lucy Waddy, shown as the daughter of Anthony and Anne Waddy, married John Tate of our James Tate family. Lucy and John Tate are father’s 5th great grandparents.

John Custis appears in my wife’s family tree as a first cousin. Tabitha Scarborough (1639-1718) married Colonel John Custis Sr (1630-1696) from whom Daniel Parke Custis descends.

While most family historians focus attention on George Washington the most bizarre stories are found in the family of Tabitha Scarborough (her father, Edward Scarborough, in particular) and in the history of Daniel Parke Junior. The Scarborough tales belong in my wife’s anthology. I will make Daniel’s story short, the long version can be found on the internet, if it isn’t broken.

Daniel was assassinated, lynched in the Leeward Islands by an angry mob of disgruntled taxpayers who firmly believed his rule as Governor should come to an end. He was the only British administrator every summarily dragged into the streets, beaten and hung.

| Wilbur Rancidbatch was here for the afternoon, flyfishing on the river and lounging in an inner tube below the rapids. He likes to edit my work from time to time and had a sneak preview of my wife’s family history which was still in the initial stages of production. He let out a loud belch of disgust at one point and I couldn’t tell if it was the beer he was drinking or the story he was reading. He then insisted that I at least make my Smith relations aware of the kind of man Tabitha Scarborough had for a father.

Colonel Edward Scarborough (1617-1671) was a burgess in the House of Burgess and the brother of Charles Scarborough who was the physician for Kings Charles II and James II. Edward was a neighbor to my wife’s Whittington and Littleton families in Accomack VA. In short, he sold guns to the Native tribes and then complained to the House that the Natives had guns. He gathered fify men, attacked the Natives, wiped out their village (women and children included) and gathered up the guns for resale purposes. On to the next tribe. He convinced a second tribe that he wanted to have cordial relations, invited them to a garden party, and gathered them in one location for a presentation. He pulled back a curtain and the Natives faced a firing squad, including a large cannon. Scarborough used his same posse of men to raid Quaker villages and isolated Quaker homes, killing some and always burning the homesteads to the ground. Not the kind of guy you want to find in a family tree. Again, he was the husband of my father’s 8th cousin, 7 times removed. I just added these notes for Wilbur’s sake. He can now point to these paragraphs and claim this as his addition to this book. |

Daniel Jr had abandoned his wife in Virginia and left her with two children when they were both still in their youth. He walked away and left her with nothing in terms of support for her and their children. He returned to England, gained the support of the Queen via a successful military campaign in Europe and acquired wealth and a string of mistresses. Given the opportunity to rule the Caribbean Islands he became a pirate and a thief, stealing from the taxpayers, raiding ships and warehouses and seizing properties. He was my father’s 6th Great Uncle. His daughter Frances Parke, the girl he had abandoned, married John Custis. John and Frances were the parents of Martha Washington’s first husband, Colonel Daniel Parke Custis.

Kincheloe Family Origins: Hy Kinsella

One of my favorite family lines in our family tree is that of the Kincheloes. The family has a rich Irish history steeped in the lore of living for one thousand years on the island of Eire. The spelling of the surname has altered over the centuries in Ireland and in the American colonies.

Kincheloes (Kinsellas) were one of our many families that settled the early American frontier. Pedigree Chart #6 on page 76 showed my father’s great grandfather Peter Smith of Posey, Peter’s father George R Smith and George’s wife Lydia Jenny Tate. The remainder of the chart shows Lydia’s ancestral line. The folks in the far-right column of Chart 6 resided in Colonial Virginia and Maryland in the 1600s. That was four centuries ago and long before the Revolutionary War.

The Kinsella clan descends from an Irish King. The clan’s kingdom, called Hy Kinsella, occupied the southeastern portion of Ireland. The area of Hy Kinsella was composed of numerous smaller states, called “tuaths”. Each tuath had a chieftain who was responsible to the the king of Hy Kinsella. The heirs of Dermot MacMurrough were eligible for kingship of Hy Kinsella. His heirs include the clans MacMurrough, Kavanaugh, and Kinsella. A powerful ruler of Hy Kinsella could become ruler of the province of Leinster. With enough strategic support that ruler could become King of all Ireland, the “Ard Ri”.

I could easily find the homestead of the Kincheloes as the lane leading to their property is still aptly named Kincheloe Road. One would have to grab a soccer ball and head south out of Clifton, Virginia on Kincheloe Road and drive two miles to the soccer fields that are built on the original plantation of Peter Smith of Westmoreland, land purchased by Peter in 1712. You would find yourself in Kincheloe Country.

Just to help you wrap your head around the generations of people that lead to my childhood home in West Chicago IL, I will put this in a linear progression.

1) Cornelius Kincheloe begat 2) John Kincheloe who begat 3) Mary Kincheloe. Mary begat 4) Lydia Simpson who begat 5) Lydia Jenny Tate married George R Smith and begat 6) Peter Smith of Posey. Peter was father to 7) James Monroe Smith who begat 8) Lebanon Smith who begat 9) James D. Smith who married Doris Weiherman and 10) Voila. So, we are going back ten generations. And we could trace the Kinsellas further back into Celtic history and find the names of iconic Celtic warriors and epic battles. Think Game of Thrones on steroids.

The earliest ancestor of the Kincheloe Family in America was Cornelius Kinsella. He appears to have been born around the year 1661 a decade after the Roundheads of Oliver Cromwell defeated and decapitated King Charles I. Stories handed down through the first century in Virginia reported that Cornelius came from Scotland, which could very well be. The Scots and Irish used the Irish Sea as a major thoroughfare and moved back and forth from one island to the other in much the same manner that morning commuters transverse the distance between Seattle and the San Juan Islands. The original location of the family line is Hy Kinsella, Ireland, ‘Kinsella’ was the Anglicized modification of the ancient name Cheinnselaig.

The first mention of Cornelius Kincheloe appears in 1693, in Richmond County, Virginia, at a location 35 miles up the Rappahannock River from Chesapeake Bay. Cornelius witnessed the Last Will and Testament of John Rice who made his will in the presence of four unrelated men. The name “Cornelius Kinselloe” appears in Court records twice in connection with this: once in a list of the four witnesses, then again in a Court Order requiring that beneficiaries of the will compensate Cornelius for his attendance in court to prove the will.

In 1695 Cornelius received a 100-acre parcel of land, at no cost, from Shadrick Williams. The reason for transaction is a bit clouded but may be tied to a scandal that rocked the community in the previous year and sullied the reputation of Shadrick. Witness the following account found in the 1694-1697 Richmond Co VA Orders; Antient Press: (Page 27), Richmond County Court 6th of February 1694/5:

“Sarah Stephens upon the Holy Gospel of God made Oath that Shedrack Williams was the true Father of a bastard Child late born of her body. Shedrick Williams and Cornelius Kinshloe do acknowledge themselves indebted to the Church Wardens of Farnham Parish on behalf of the said Parish in the sum of Ten thousand pounds of tobacco to be paid b.c in case the said Shadrick shall not save harmless the said Parish from the maintenance of a bastard Child late born of the body of Sarah Stephens and by her Oath declared to be begotten by the said Shadrick. Forasmuch as Sarah Stephens hath declared herself guilty of the filthy sin of fornication with Shadrack Williams, the Court have ordered that the said Sarah do pay suffer such paines and penaltys as by a late Act of Assembly it is made and provided.”

I have copied this verbatim and I am shaking my head in wonder. How many ways can a clerk spell one name, in a simple paragraph? Could the clerk not stop inputting data long enough to simply ask Shadrick, “How do you spell your last name again?” Admittedly, I found numerous varied spellings of his name in the archives, but three variations in one paragraph, authored by one clerk sets a record.

And then there is the mumbo jumbo of colonial legalese. For the sake of all that is carnivorous, what does any of this gibberish mean? Where is my Scotch? I need a drink. I get the fact that Sarah Stephens is pointing the blame for her baby on Williams. The baby was born out of wedlock. Understood. She was “guilty of the filthy sin of fornication with Shadrack Williams.” But how did Cornelius get dragged into this? He seems to agre that he is indebted to the church wardens of Farnham Parish to the tune of 10,000 pounds of tobacco. That was a bit of ‘cash’.

The only thing I can come up with to explain events related to Sarah Stephens, Shadrick Williams and Cornelius Kincheloe and the 100 acres of land, is this, and it is pure conjecture on my part: Cornelius married Anne, the bastard daughter of Shadrick Williams and Sarah Stephens.

The 100-acre plot was a dowry that accompanied women as they stepped into marriage. Williams owned up to the fact that he fornicated with Sarah Stephens and was Anne’s father. Cornelius loved Anne, married her and covered the cost the church incurred in raising her to adulthood. The child, Anne, was born years before the paternity case ever hit the Richmond County Courthouse. The church wardens surfaced the issue to recover their investment and accepted the 10,000 pounds of tobacco in payment. I don’t know. There isn’t a lot of evidence identifying the wife of Cornelius other than this scrap of paper referencing the “filthy act of fornication.”

Author’s Note: In 1996, after years of painstaking research, a gentleman by the name of John Kincheloe III identified the 100 acres where Cornelius Kincheloe built his first homestead. Cornelius was the 8th generation grandfather of John III (1996). Incredibly, a parcel of the land was about to be auctioned off in 1996 and John III quickly drove from his North Carolina home to the auction. He snapped up 3.5 acres of the original Kincheloe tract! Three hundred years after Cornelius Kincheloe tilled the land and planted tobacco, a present-day descendant can play frisbee golf on the land of his immigrant ancestor.

It was on this 100-acre piece of land that Cornelius built his family’s first home, a two-room house at most, encircled by a split rail fence. His land sloped down to a sandy marsh in the Tidewater Basin. He maintained a path and bridge on a creek first called Oatspekety, then the Horse Bridge Swamp, later called Bryers, then Jugs Creek. The property is less than two miles south and west of present-day Warsaw, Richmond County, VA.

A typical home in Richmond County would have been a one-and-a-half story wooden house. A successful farmer might occupy a two-room ‘Virginia Home,’ built around a brick chimney. Cornelius’ first house probably had a chimney that was made of wood and lined with plaster or fire-baked clay. Candles and lamps were rare, so this fireplace provided the only light available for an evening of craic, reading or simple relaxation.

While Cornelius did not leave a Last Will that could be found, or the mandatory inventory that itemized everything he ever owned and left behind at his death, we do know from the inventories of those whose lives were spent in his hood what may have been found in his 17th Century dwelling.

Life was a bit stark for our immigrant ancestors. It took time and hard work to create wealth. Inferring from the inventories of his neighbors’ we can surmise that Cornelius and Anne probably owned a bench, a chair, a table, and a storage chest which doubled as a chair. A few shelves might occupy a wall. An iron pot would be found hanging in the fireplace alongside a large pewter spoon for cooking. Smaller spoons were used by the family to scoop food from homemade bowls and plates.

The typical frontiersman owned an old knife, an axe to fell trees, a couple of saws, and a wedge for splitting wood. Wood was a most valuable commodity. With it a family could have heat for warmth, cooking and light. Trees provided the timber needed for building homes, fencing, out buildings and bridges. We would find assorted iron nails, a hoe for gardening, a water bucket, a wooden mallet, and a length of rope. A long wooden chest would hold a man’s carpentry tools. Stacked to one side of the house we would find several barrels of staple crops: dried corn, dried beans, and salt. Salt was vital.

Clothing and bedding were distributed among the loved ones in a will: Cloth from England, a cloth waistcoat and leather shoes for church service, a deer hide coat and leather moccasins for work. A planter’s hat would keep the sun and insects off the head. The mattress the family shared on the floor at night was stuffed with straw or cattail fiber. Those who could not fit on the mattress slept on animal hide mats.

Cornelius probably had a yard very much like our own present-day plot in the Northwoods: a large woodpile, a vegetable garden, perhaps herbs as well and several apple trees. Hopefully his trees did better than mine. Damn nursery sold us some sterile trees that yield a fine nest of tent worms that look like ugly little gummy worms. Anyway, I digress. Cornelius maintained a stand of evergreens for a lifelong supply of wood. A majority of his 100 acres, once cleared of rock, forest and stumps would be planted in a tobacco field that would eventually tire of yielding the cash crop and give way to the less demanding corn fields. The loss of income would force the Kincheloes and their neighbors to pick up and move inland.

Cornelius found a social life via his connections at church. The congregation offered more than just a sermon on Sunday. The church was a support group for those who remained faithful to the core group and Christ. Cockfighting and horse racing provided entertainment. The Taylor family at Mt. Arie owned a track and a fine stable of champion horses just down the road, as did other families who took pride in racing. James Lea, the neighbor of Peter Smith was a renown breeder of roosters for the fight clubs of his day. While Lea lived in North Carolina, he was known to travel a good distance to capture valued prize money.

Written documents of the time revealed the importance of both church and judicial proceedings related to wills, inventories and deeds. But church and courthouse also offered gossip revealing affairs, use of obscenities and altercations. A long day in court could easily end in the local ordinary or tavern.

The usual life-threatening elements clouded over the Kincheloe home. The diseases that crawled out of the Tidewater swamp at Jamestown were still killing people. The southern climate alone with intense heat and humidity stifled the life out of many a Brit accustomed to the cooler temps of England. There was always the lingering fear of Indian attacks and reprisals.

John Kincheloe (1685-1745)

By 1724 after the death of Cornelius, his son John sold the original 100 acres acquired from the philandering Shadrick Williams. John moved his family into the Bull Run neighborhood of Peter Smith and sons, including our own James and Elizabeth Taylor Smith. Cornelius died sometime before 1718 in Richmond County, Virginia. I should point out that the county and the city were not the same and not even proximate to each other. Richmond County lies along the north shore of the Rappahannock River on the Great Neck of Virginia. It shares the peninsula with Westmoreland County to the northwest and Northumberland County to the northeast. The city of Richmond VA is a good 50 miles to the south. One must cross the Rappahannock and five other counties to get there.

I find it easy to nominate Elizabeth Canterbury as the wife of John Kincheloe. Everyone else building a family tree has subscribed to the thought that she belongs in John’s bed. Say no more. Say no more. But most of my evidence is circumstantial and circumspect and that is two ‘circums’ too many to allow me to say with certainty that John married Elizabeth Canterbury. The confusion regarding the role of Elizabeth Canterbury in family trees results from years of faulty research by previous generations of family historians.

An investigation by present day historian, John III, found that early oral history had confused our John Kincheloe with one John Canterbury who married an Elizabeth, the daughter of William Smith, who just happened to live in Peter Smith’s neighborhood in Westmoreland. William Smith is found conducting business with our Peter Smith. It would be easy to jump to the conclusion that John Canterbury died as a young husband and left Elizabeth Smith Canterbury free to marry John Kincheloe. But no, that didn’t happen. The Canterbury clan was busy producing offspring in tandem with John and Elizabeth Kincheloe. This provides just another insight into the headaches one can encounter when digging in a graveyard.

The Canterbury family has an interesting history, a few Tales to tell. I suspect a few folks among previous generations of greedy historians propped Elizabeth Canterbury up at the dinner table as an iconic figure, a piece of Chaucer’s historical vignettes. The 14th Century Tales have nothing to do with 18th Century Canterburys.

John Kincheloe put at least eleven kids on this planet. I could name all eleven, but this book would become overpopulated in a hurry if I identified every child born to everyone carrying our DNA. Let’s stick with the skinny version of this tree. It is already fat enough. John’s daughter Mary was born in 1719 in Richmond County and appears to be the first born of the brood. Twenty-one years later (1740) the last of the litter, Sarah, was born in Prince William County (Hamilton Parish). So, mother Elizabeth was either walking pregnant or giving birth. Her adult life was spent reproducing, which does seem to be the stereotype for married women at the time. While we descend from Mary Kincheloe, many of her siblings (our great aunts and uncles) do form a support group for our direct ancestors. One, 5th great aunt Elizabeth Kincheloe, married Isaac Davis, father of Captain Jesse Davis, our first cousin, star of a pending story and hero of Nelson County KY.

On “this Twenth day of Aprell 1722” John Kincheloe sells “Tenn akers” of land to William Smith of North Farnham in County of Richmond. He parts with the land for the small sum of five shillings currant money. The land sold is adjacent to one Roger Williams. The deed goes on to describe lot lines as they relate to various species of trees found in the Great Neck of Virginia: Gumm, Mapell, red Oak, ring white Oak and finally “a line of marked trees.” All these references to trees in colonial deeds makes a guy wonder what happened to property lines when a hurricane came onshore. Witnesses to this transaction between John Kincheloe and William Smith included one Robert Smith. The year is 1722 and yes, our Peter Smith did have a known son, William who was an adult in 1722 and purportedly a second son Robert who had become a circuit riding preacher. But there were other Smiths in the Great Neck as well, so we must be careful. And the bottom line is, who really cares when we are talking shirt tail relatives any way. This is no time to become anal retentive and quibble over minor details.

The reference to Roger Williams is intriguing. New England preacher, Roger Williams (1603-1683), coined the phrase “Separation of Church and State,” and was the founder of Rhode Island. The Roger Williams found in this deed was the son of the infamous fornicator Shadrick Williams, the man who originally deeded one hundred acres to our Cornelius. Shadrick Williams was the brother of New England preacher, Roger Williams (1603-1683). The hero of Rhode Island history is a 6th great Uncle to my father.

On June 2, 1724, John Kincheloe sold the remaining 90 acres to Robert Smith for 6,000 pounds of “good and weighty tobacco” packed in casks. Now here is a piece of evidence I also find interesting:

“John Kincheloe came into Court and acknowledged his Deeds of Lease and Release for Land unto William Smith, which was admitted to Record, Also Elizabeth Kincheloe, the Wife of John Kincheloe, appeared in Court and relinquished her Right of Dower in the land conveyed in the Deeds unto William Smith, which was also admitted to Record.”

Land transactions were almost exclusively made among men who viewed women as second-class citizens. But the phrase “right of dower” and a woman’s signature became important if the woman brought her family property into a marriage, or if the buyer wanted to insure there would be no future claim made by the wife on that land, should her husband die and leave her scrambling to make ends meet. If Elizabeth brought the acreage into her marriage with John, then the question arises: was she a Smith at birth (not a Canterbury)? Was she married to a Canterbury prior to he marriage with John Kincheloe?

In the real world of historical documents, we find information that helps us establish the Smith neighborhood in Prince William County. John Kincheloe divested himself of his father’s homestead in Richmond County and headed north and west of Washington D.C. to Bull Run. This was before there was a Washington D.C. and before there was a George Washington. The year was 1732 and the deed was completed 10 days before the birth of George Washington on February 22, 1732. While Kincheloe is neither an actor in this case, nor a witness, he is referenced as a neighbor to the property in this deed:

“Feb. 13, 1732: Prince William County, Virginia Deeds, John MacDonnell and Ana his wife of Parish of Hamilton in Prince William to Nimrod Hott and John Jeremiah Heiss of Parish and county aforesaid…. for 4000 lbs. of Tobacco 160 acres upon the branch of Flores Cr. and Niapsco joyning land of Abraham Farrow, John Kincheloe, William Leach and Coll. John Tayloe….on no. side William Corums tobacco ground.”

The description points to Kincheloe’s Prince William Property and identifies his neighbors. Among the folks in the hood we find Colonel John Tayloe. The Colonel is the same John Tayloe I (1688-1747) identified as the father of Elizabeth Taylor. No one knows why Taylor changed the spelling of his last name from Taylor to Tayloe. Part of some branding process perhaps.

“A second Prince William deed executed on August 26, 1739. John Kincheloe of Hamilton Parish PrinceWilliam., Gent. to John Gregg of same, Gent….for 40 lbs. current money 169 acres between head branch of Hoos Creek and branch of Neapsco in Hamilton Parish corner John Wallace ….line of Wm. Feakland….near house of William Bayley it being part of 228 a. gr. to William Champe by patent dated July 15, 1725 ….deeds of lease and release. John Kinchelo Witnesses: Wm. Henry Terrett, Peter Daniel, James Halley.”

John divests himself of 169 acres of land on Hoos Creek and Neapsco in 1739. His neighbors included William Bayley. It is probable that this William Bayley married the granddaughter of Peter Smith of Yeocomico. In his will Peter (1741) divests himself of all properties on the Nominy River in Westmoreland and in Prince William County. A parcel of the land in PWC goes to granddaughter Anne Bayley, referred to also as “daughter of my daughter Anne Thomas.” Anne Thomas, wife of Hugh Thomas Jr died in 1718 and left two sons and a daughter, Anne, who married a Bayley. This bequest follows the colonial practice of dividing properties and including the survivors of the deceased sibling in the distribution of benefits.

Returning to the Kincheloe deed for a moment: “Hoos Creek” was named after the Hooe family of Westmoreland County. They were Peter’s neighbors on the Potomac River in the previous century.

Finally, the Kincheloe deed dated July 22, 1749 reveals that John Kincheloe died previously and left properties to two sons: Cornelius and Daniel. The properties lie on Rushy Branch of Bull Run. Cornelius is selling his 215 acres to an Edward Emms. We know zilch about this Cornelius, where he went next or if he soon died is not known.

We do know that his brother, Daniel, married first Elizabeth Wickliffe and after her death, secondly, Susannah ‘Sukey’ Davis. In 1761 Daniel Kincheloe is witness to the sale of a 150-acre property that is described as on Powell Creek of the Potomac River and adjacent to lands owned respectively by Isaac Davis and John Bland. Isaac Davis is my 6x great uncle, the father of Captain Jesse Davis, my fifth great uncle.

Editor’s Note: We get the picture. Your ancestors had a lot of friends and relations who spent two centuries roaming the land in Westmoreland County, then Prince William County and Bull Run. Some of these people were rich and famous, many of them were heading west before scattering in all directions. So where are you going to drag us next? Because, frankly my head is full, and I can’t follow this much longer without a glass of good, robust wine.

Mary Kincheloe (1719-1798)

John’s first-born child, Mary, was born in Richmond County and grew to young adulthood in Prince William County (PWC), on the banks of Bull Run and Occuquan Rivers. The Kincheloe’s PWC property was near the Peter Smith family and the family of Richard Simpson (1692-1762). Her life would become intertwined with both families by way of marriages.

The Kincheloes and The Burnt Station Massacre

My father had heard tales of a massacre that had taken the lives of several of our ancestors. During my research I have listened to the taped history dad provided prior to his own death. I have gone into the archives and found several such encounters with Native populations who were resisting the westward movement of immigrants into their nation. The Long Canes Massacre was one such encounter, Burnt Station is one of several more.

From the moment that Europeans set foot on the American continents (North and South) and accompanying islands, the advancement of the western ‘civilization’ came at the expense of those humans native to the land, the Native American. I like the way Canada has addressed that reality by identifying the indigenous tribes as the First Nation. While it is clear the tribes were never organized as one nation, nor operating in unity on even a singular issue, the fact remains: the future of their culture was threatened by even the least insidious of our ancestors.