Where to go Next in This Collection of Stories?

Days later I returned to my desk. I shuffled through the papers looking for a cigar I had smuggled in from the village cigar shop, which has since shuttered the windows and barred the door forever. Every once in a great while I enjoy an Acid Blonde cigar or a Park Avenue Connecticut. I found the cigar butt I needed and moved to the back deck. I stared into the roiling waters of the river below. A snowmelt and heavy Spring rain made the river very entertaining. Occasionally an otter family would slink along the far shore. A voice boomed out from upstream, in an area that had become a log jam that would stop a kayak in place. And it did, but not a kayak. I stared in disbelief and began tottering at a high speed down the steps of the deck, heading down toward the river. “Wilbur? What in the hell were you thinking?”

“More like what was I drinking, Doc! I wanted to float over here in my new john boat, but the river disagreed with me!” Wilbur’s boat was upside down and lodged in the usual debris that gathers behind a fallen tree in the Spring runoff. He was perched on a promontory point in midstream, his ass partially submerged in the cold waters of the Spring melt.

“I had a little gift for you, my latest creation. I know you like a dark, coffee flavored stout and I had one for you in the boat. But I am afraid the river took it when I spilled.” I helped Wilbur recover the boat with the aid of a Come Along Wench strapped to a large oak on the shoreline. I offered him my Scotch and a fresh Acid Blonde cigar I had intended to savor prior to his arrival. It’s the least I could do knowing Wilbur had risked his life and failed to deliver his latest brew.

“Do you think I should notify the DNR that I polluted the river? That beer had an IBU of 110 and if it leaks into the stream the isomerized alpha acids could kill a fish.”

I discouraged Wilbur from making the call. I would recover the bottle from among the logs when the spring floodwaters subsided. Now I don’t make a habit of smoking old cigar butts, but an Acid Blonde is not something I want to consider garbage at any point in its’ existence. I found the remnants of a good cigar in the ash bucket by the fireplace and joined Wilbur at the edge of the stream. His wife Gerda was in the vicinity hunting for morel mushrooms and happy to take him home, much later in the evening, much later, early morning in fact.

I often think of my father when I smoke a cigar and how hard I have tried to not be him. I picture him chain smoking Corona cigars and I wish he were here. I would offer him a Cohiba, but he would scoff at it and light up his Corona and wonder how I became so pretentious.

I would offer him a Scotch whisky, but he would look past the whisky and ask for a martini: “No vermouth, no angostura bitters, just ice. An olive if you have one. Gordon’s if you have it.” It was the choice of James Bond, after all. Death’s Door and St. George gins never made it to my dad’s palate. After centuries of living as a yeoman on the doorstep of the aristocrats, I have arrived. To my way of thinking, it is all a state of mind any way.

My father and grandfather would hold me in their verbal grasp when they talked of our ancestors. I learned so much from them and yet, so little. I have so much more to offer my father now that I have spent decades locating the answers to his question, “Who was Peter Smith, and did he really come off the battlefield at Waterloo?” I know exactly what Dad would say if I told him that Peter Smith and the Davis family came from slave plantations in North Carolina.

“The Hell you say?!”

The Davis Immigrants

I enjoyed the last of my cigar and returned to my desk half wondering what part of the family I would expose next. I sorted through the index cards, brushed aside some legal pads and a collection of papers fell from the shelves above and landed in my lap. I picked up a monogram and scanned the header, Relation of a Voyage to New England, 1607-1608, author James Davis.

“The Hell you say,” I muttered. Was someone trying to tell me something?

Tracking the family history of Sarah Davis Stilley, her father William, Esq and his father William Sr, was made difficult by the mere fact that Virginia and Albemarle (NC) were overrun by pioneers with a Davis pedigree. It was as if Wales had purged itself of anyone with the surname ‘Davis’ and flooded Coastal Carolina and Virginia with various members of the clan, all named James, John, William, Samuel and Richard. The women were primarily named Elizabeth or Sarah, with a few exceptions. Davis families escaped Wales in two separate waves, separated by a century of time. The earliest of the Davis clan arrived in present day Maine in 1607 and just as quickly returned to England. “Too damn cold,” one of the family muttered as he chipped the ice away from his manly beard. “We discovered a use for plaid, but that was about it.” It was from this family that we descend and so I will begin at the beginning.

The same Davis men came again a year or two later to stay and prosper in Jamestown, Virginia, and eventually brought their wives and children. It was a tad bit warmer than coastal Maine, but the heat and humidity in summer was a killer. This clan, the sons of Sir Thomas Davis (1550-1601) an investor in the London Company of Plymouth, settled in Jamestown, Henrico and Warricksqueke in the first decades (1609-1635) of our nation’s prenatal life experience. Be aware of any family historians who try to tell you on the idea that Sir Thomas (1550-1601) moved to Virginia. I see examples of that copied and pasted all over the internet. He lived a lavish lifestyle in England and had no need to give it all up when he could send the kids out on various adventures to take care of family business. And besides, his death date (1601) predates any lasting British colonial settlement by a decade!

I entertained the notion that our Davis kin descended from a second wave of family pioneers arriving in the colonies in the 1730s and thereabout. That hypothesis did not pass scrutiny for a variety of reasons related to history, religion, and geography.

The Arrival of the First of the Davis Brothers

Sir Thomas Davis of the London Company had several sons, several of whom settled into the Virginia plantation system along the James River and Chesapeake Bay. The sons included James, William, Robert, John and Walter. I knew all about James Davis 50 years ago when I studied history and 40 years ago when I taught history. He was the guy who was always getting second billing. He was the warmup act for Humphrey Gilbert, Captain John Smith and Sir Walter Raleigh. His name seldom gets mentioned in high school history classes. I passed over him for a reason when I taught history. It was an opportunity cost. If I spent too much time on a James Davis, I would never be able to cover Dwight Eisenhower, Jack Kennedy or Elvis Presley.

I knew enough about James Davis of Jamestown, to know that I did not want to descend from him. Suffice it to say, he could have easily been nicknamed, “The Butcher.” Captain John Smith, no relation, thought peaceful coexistence and fair trade with the Natives on the James River would ensure success. Use force if necessary but coexist. Davis preferred an Old Testament approach: an eye for an eye, and annihilation if necessary; and even when not necessary.

Of Welsh origin, the Davis family produced seafaring men and planters. In 1583 Robert Davis was the master of Sir Walter Raleigh’s vessel, the Rawley which sailed in Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s expedition to Newfoundland. Humphrey was my wife’s many times great uncle on her mother’s side of the tree. He descended from Otho Gilbert (1420-1494). Otho was Nancy’s 16th great grandfather. It was the Age of Exploration and Humphrey Gilbert was looking for the Northwest Passage through the Arctic Ocean to Cathay (China).

Humphrey also intended to claim 9 million acres of Newfoundland tundra and a sea full of North Atlantic cod for Queen Elizabeth of England. The Queen may have had an interest in developing the Fish and Chips industry in England. Sir Humphrey had recently decimated the population of Ireland in his quest to destroy my Fitzgerald clan (first cousins). Having conquered Ireland, it was expected that Humphrey would be named the overseer of Ireland. The Irish were not excited about the prospect and showed no early interest in links golf.

A man of many talents and a troubled mind, Humphrey Gilbert and his half-brother, Sir Walter Raleigh, turned their attention to the colonization of the New World. Humphrey had his heart set on colonizing New England and Virginia. While returning to England from Newfoundland, Gilbert insisted on sailing his favorite, but very small ship, the Squirrel. More experienced sailors advised him to sail home on one of the larger ships. But Gilbert prevailed. He should have listened to the experts. He loved this small but rugged ship; and it was his money after all that financed this fleet. He stayed put on the Squirrel and was often observed sitting in the stern of his small frigate reading John Milton’s Paradise Lost. True story.

A North Atlantic storm ripped into the fleet and even the larger ships were tested by the enormous waves and gale force winds. The largest of the ships, Golden Hind pulled within cell phone range, per the story told, to check the condition of the Squirrel. The crew heard Gilbert cry out repeatedly, “We are as near to Heaven by sea as by land!” as he lifted his palms to the skies to illustrate his point. The line uttered was a paraphrase of a Milton passage. At midnight the lights of the Squirrel disappeared. The ship was overwhelmed by massive waves and all aboard were swallowed up by the sea. Humphrey Gilbert’s dreams died with him and were left for others of our family to pursue.

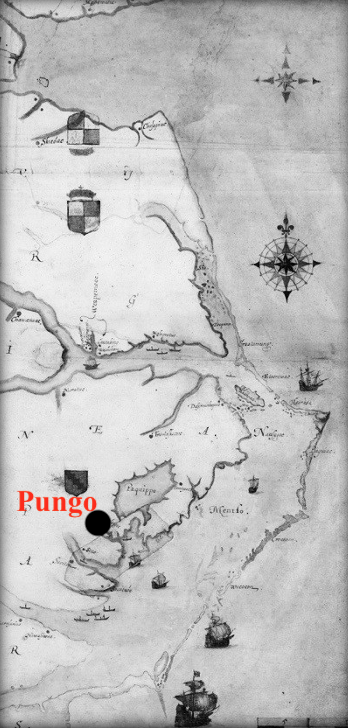

“Others” of my wife’s family, the Raleighs, Grenvilles and Drakes, picked up where Gilbert left off. They established what became the Lost Colony of Roanoke (1590) on the Carolina coast (See Left). Yet another disaster. Look it up if you are not familiar with the bizarre tale. I have included this 1575 rendering of John White’s watercolor painting of the Carolina coast. This is obviously a black and white image. The original is painted in various colors and can be found online. White, a wealthy artist, was the Governor of the Lost Colony and left his family (including Virginia Dare) on the Island as he returned to England for much needed supplies. After many disasters, he returned three years later to find the encampment deserted, his family gone from his life forever, swallowed up by the New World. The lands that became the plantations of the Davis and Wilkinson families one century later, were located at the lower left of this image.

“Others” of my wife’s family, the Raleighs, Grenvilles and Drakes, picked up where Gilbert left off. They established what became the Lost Colony of Roanoke (1590) on the Carolina coast (See Left). Yet another disaster. Look it up if you are not familiar with the bizarre tale. I have included this 1575 rendering of John White’s watercolor painting of the Carolina coast. This is obviously a black and white image. The original is painted in various colors and can be found online. White, a wealthy artist, was the Governor of the Lost Colony and left his family (including Virginia Dare) on the Island as he returned to England for much needed supplies. After many disasters, he returned three years later to find the encampment deserted, his family gone from his life forever, swallowed up by the New World. The lands that became the plantations of the Davis and Wilkinson families one century later, were located at the lower left of this image.

Our Davis family would settle eventually at the fork in the major tributary (Pungo River) shown in White’s early map.

Key among the captains that piloted English ships were the sons of Sir Thomas Davis. James and Robert were involved in the early settlement of first Maine and then Jamestown. The British had been inspired by stories of Norumbega, a colony believed to have been established by the Vikings in the year 1000 and then forgotten. French navigator Jean Allefonsce (1542) had sailed the New England coast south from Newfoundland and discovered a great river, called the Norumbega. He sailed up that river and found a city of tall white people who spoke a language that ‘sounded like Latin.’ Later explorers believed the river was the Penobscot. Norumbega remains one of those mythical places on earth for which there is little evidence other than hearsay.

Gen 14: James Davis (1575-1623)

My Father’s 10th Great Grandfather

Born around 1580 in Gloucester, England, James Davis was the son of Sir Thomas Davis, a man invested in the Plymouth Company. Fifty years after the voyage of Jean Allefonsce, the Plymouth Company was determined to go forward with a colony on the estuary (or mouth) of the Kennebec River, in present day Maine. James and Robert Davis became responsible for developing Fort Sagadahoc. James Davis, a bit of a Renaissance Man, provided us with a vivid account of the voyage in his journal, Relation of a Voyage to New England, 1607-1608. The guy had a talent for writing. He was engaged in a competition with Captain John Smith who was also journaling his travels along the North American coast.

Davis dropped off his settlers at Sagadahoc and returned to England in the late summer of 1607. The colonists had arrived too late to plant crops and did not have the proper supplies to endure a bitter winter. Half the population returned to England in December of 1607. The remainder toughed it out and kept busy with the task of building a ship. They cut timbers, crafted a 50-foot ship and christened it Virginia. While the original intent was to demonstrate that the forests of New England and accompanying shoreline would offer great opportunities for ship building and future investment, the fact is, the colonists wanted to get up and out of there.

Political turmoil divided the small population as factions supported two separate leaders. George Popham, the son of the financier of the project, Sir John Popham, was designated by the Plymouth Company as Colony Leader. Nepotism was alive and well and off to a rough start in New England. Raleigh Gilbert, second in command and son of Humphrey Gilbert, also had access to large bank accounts, and a fanbase among the few settlers.

The leadership conflict was short lived. George Popham died in February of 1608, leaving Raleigh Gilbert as the uncontested administrator. In the Spring of 1608 word arrived that the man whose money they needed, the man who provided the supplies, Sir John Popham (father of the deceased George Popham), had also died in England. With both Pophams deceased it seemed the Sagadahoc effort should end. Raleigh Gilbert would not give up this venture so easily. He returned the recently arrived ship to England with cargo and resources gathered over the year and hoped to create a profit for the company investors.

Raleigh Gilbert’s plans were altered quickly. Word arrived on the next incoming supply ship that his older brother and the heir to Humphrey Gilbert’s fortune had died. Raleigh was now the heir to Humphrey’s fortune, and he was going to head home and enjoy the windfall that had come his way. The remaining colonists chose to leave and fold up the endeavor that had been the Popham Colony (aka: Sagadahoc). Raleigh Gilbert carried passengers’ home on the ship, Mary and John and James Davis carried the remainder of the small population to England on the Virginia with James Davis as captain of the ship.

James Davis didn’t sit still for very long. He was needed in Jamestown, Virginia. On June 18, 1609 nine ships set sail from England in what was called The Third Supply. Davis once again guided the Virginia. Nine ships were transporting supplies and settlers to the colony. Jamestown was struggling for survival. The colony was headed toward desperate straits. A period of drought was now in its’ seventh year. Food supplies were dwindling.

The ships faced their own struggles for survival at sea. Hurricanes were something new in the life of a British sailor. High winds between the Canary Islands and Bermuda sank one ship (the Catch) and all on board were lost. A second ship, Sea Adventure, limped into Bermuda beyond repair and was disassembled. Two ships were created out of her parts: Deliverance and the Patience. Folks in Jamestown had given the passengers of the Sea Adventure up for dead. Things like that happened on the ocean. We had relatives on the Sea Adventure who survived the ordeal and became part of British lore. I will include more on them at a later point on this pathway through the past. Shakespeare’s, The Tempest, was based on the calamity.

James Davis was blown off course. His ship, Virginia, struggled to survive in the high winds and arrived in Jamestown two months after the first fleet of ships had arrived. Captain John Smith (no relation) had little use for James Davis and was not moved by his arrival and survival. Smith worked for the Virginia Company and Davis for the Plymouth Company. The newly created ships, Deliverance and Patience, arrived from Bermuda one year later. Their appearance in the harbor at Jamestown stunned the colonists who assumed the Sea Adventure and all aboard the great ship had been lost at sea.

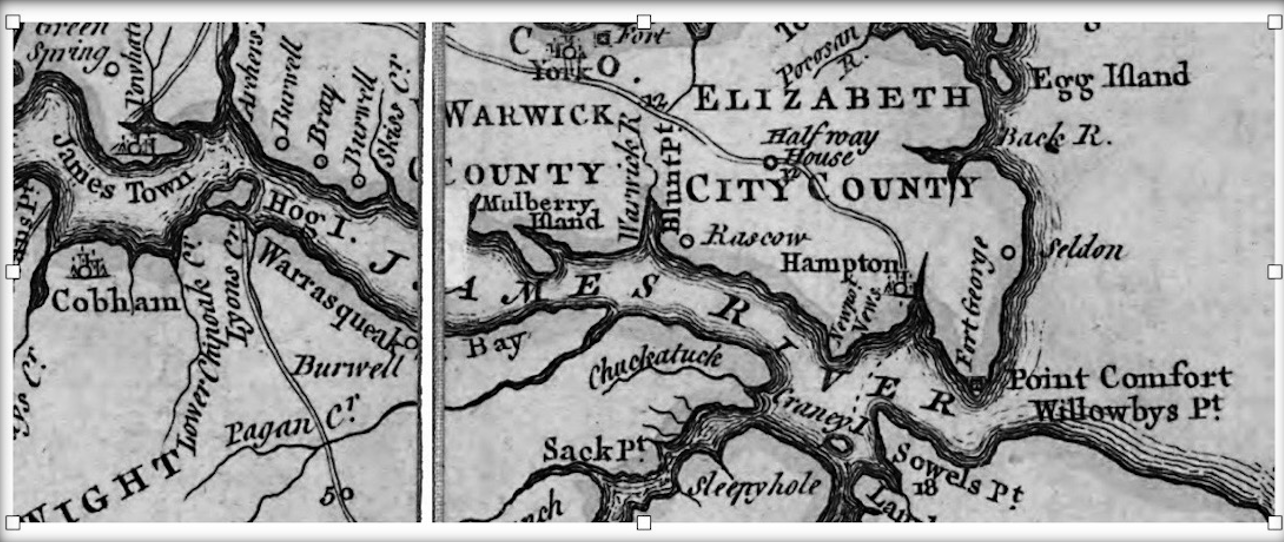

Map of James Town and James River Estuary

Map of James Town and James River Estuary

Once he got his boots on the ground in Jamestown, Davis stayed put for a long while. He took charge of Fort Algernon, thirty miles downstream from Jamestown at Point Comfort. The fort has also been named Fort George, Fort Henry and Fort Monroe.

It was a dangerous assignment. Chief Powhatan had captured Smith’s predecessor, Captain John Ratcliffe, and skinned Ratcliffe while he was still alive and burned him at the stake. When Captain John Smith returned to England the door was left open for Davis to assume a greater military presence. He would take no chances with Powhatan and was aggressive, and sometimes ruthless, in his attacks on the tribal villages in the area. Having heard of how Ratcliffe met his death, one can understand Davis’s proclivity for violence. He secured the region for the time and the British counted on his military leadership as they developed forts and went toe to toe with Powhatan and his tribe. Attacks and counter attacks were now commonplace. On any given Sunday one side could easily rout the opposition. It was the fore runner of NFL football minus the billion-dollar stadiums and ten-dollar hot dogs.

The Davis tactics of annihilation were the subject of debate in the Company board room in London. Some rued the fact that they had brought Smith home to London. Smith had been able to maintain a relative peace and trade relationships with Powhatan. Others appreciated the lack of respect Davis had for the Native population and reminded Smith’s adherents that Captain Smith was a narcissist and self-promoting know it all who smelled of cod oil and flounder entrails. Moderates found Davis to be far too ruthless and feared that his eye for an eye approach could only escalate and exasperate living conditions for the small population at Jamestown. The board members eyes were on the bottom line, corporate profits. The investors wanted a return on their investment.

Violence of a different sort soon devastated the colony. Starvation gripped Jamestown in the winter of 1609-10 as Powhatan laid siege to the fort in James Citte. He issued an order that his warriors should attack any colonists or livestock found outside the fort. Percy later wrote that, “Indians killed as fast without [the fort] as Famine and Pestilence did within.” Percy’s journal was graphic. He wrote that to satisfy their “Crewell hunger,” some went into the woods looking for “Serpents and snakes, and to digge the earthe for wylde and unknowne Rootes,” but those people “weare Cutt off and slayne by the Savages.”

Starvation weakened the colonists and led to sicknesses such as dysentery and typhoid. The colonists ate shoe leather and butchered seven horses brought from England the summer before on the ill-fated fleet. Percy wrote, “Then, having fed upon horses and other beasts as long as they lasted, we were glad to makeshift with vermin, as dogs, cats and mice.”

During ‘The Starving Time’ three-quarters of the English colonists in Virginia died of starvation or starvation-related diseases. The population dropped from 500 to 60 in the Spring of 1610.

There were charges of cannibalism: Starving settlers dug up “dead corpses outt of graves” to eat them, and others “Licked upp the Bloode which ha[d] fallen from their weake fellowes.” Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists in 2012 uncovered the first forensic evidence of survival cannibalism in a European colony in North America.

In his unpublished account A Trewe Relacyon, George Percy, who served as President of the Council during these grim months, wrote that Englishmen felt, “the sharpe pricke of hunger which noe man trewly descrybe butt he which hathe tasted the bitternesse thereof.”

During ‘The Starving Time’ Captain Percy himself nearly died of starvation. When he was able to recover, he decided to float down the James River to see how the folks at Fort Algernon were doing. He had no idea what he would find. Was Davis even alive? Were his troops still holding the fort? Had Powhatan seized the fort? Had starvation wiped out the garrison? What Percy witnessed on his arrival at Fort Algernon was one of the least discussed moments in American history. I will let him relate his observations and experience. Unfortunately, you the reader are going to have to translate into present day English.

“By this Tyme being Reasonable well recovered of my sickness I did undertake a jorney unto Algernon Fort bothe to understand how things weare there ordered and also to have bene Revenged of the Salvages att Kekowhatan who had treacherously slayne dyvers of our men. Our people I fownd in good care and well lykenge haveinge concealed their plenty from us above att James Towne.”

“Beinge so well stored thatt the Crabb fishes where-with they had fede their hoggs would have bene a greate relefe unto us and saved many of our Lyves But their intente was for to have kept some of the better sorte alyve and with their towe pinnesses to have Retourned for England nott Regardinge our miseries and wants at all; wherewith I taxed Capt: Davis and tolde him thatt I had a full intente to bringe halfe of our men from James Towne to be there releved and after to Retoourne them backe ageine and bringe the reste to be susteyned there also and if all this woulde nott serve to save our mens Lyves I purposed to bring them all unto Algernowns foarte Tellinge Capt: Davis that another towne or foarte mighte be erected and buylded butt mens lyves once Loste colde never be recovered.”

I know. It’s difficult to read, like a second language written by someone who didn’t buy the Spell Checker available at the local bookstore. This is why Shakespeare lost me at hello. What Percy found on his visit to Fort Algernon blew his mind. While food was virtually gone in James Citte, James Davis and his garrison of twenty survived in a hearty manner on the seacoast. Twenty miles removed from Jamestown and sitting on the Chesapeake Bay, Davis and his men had a steady supply of seafood and were able to keep their hogs well fed on crab meat. When Captain Percy of James Citte visited the fort to see how everyone was doing, he was stunned to find everyone healthy and strong. Starvation was not an issue as it was in James Citte, aka Jamestown.

While Percy was starving, Davis and his men were tossing frisbees on the beach and playing Super Mario Kart. It is rumored that during this time Davis had invented the lawn chair and that little umbrella thingy that goes in his signature drink, The Hurricane.

Percy expressed his anger in his journal and directed Davis to move fast to remedy the situation in James Citte. He believed Davis knew of the starvation and that Davis deliberately withheld food from Jamestown. He ordered Davis to provide food, care and shelter for all who were victims. James Davis had little use for John Smith and Smith’s Jamestown. It appears Davis would have been delighted to see the Jamestown venture fail. That was Percy’s perception. John Smith was not in Jamestown that year. He had been removed by Corporate to England, subjected to Board scrutiny and interrogation. Whether it was mutual dislike that drove Smith and Davis apart or the corporate conflict between two companies, Plymouth and Virginia the situation in Jamestown had become untenable.

Plymouth and London Company Charters

James Citte was a corporate project owned and operated by investors in the London Company of Virginia. Queen Elizabeth had agreed to a corporate driven development of the American coast. Two companies had been granted charters and given rights to colonize the new lands. Boundary lines were drawn to clarify rightful territories and those lines allowed for 3 degrees of separation. Plymouth Company reserved the right to settle lands north of 41degrees north latitude. London Company was able to settle as far north as 38 degrees N Lat.

The section in the middle, found between 38- and 41-degrees North Latitude, contained present day New Jersey, Maryland, Pennsylvania and the Delmarva Peninsula. This territory was left in question and would be awarded to the company that did best in settling the domain it had been granted. It was an early version of The North vs the South in the 17th Century.

This apparent neglect of the middle ground, shown here in yellow, was viewed by the Swedes and Dutch as an opportunity for colonization. Guys like our Olaf Stille and Wolfert von Kouwenhoven rushed in to fill the void. The Spanish were developing colonies to the south in Florida and Georgia. Finding no gold ore, they were slow to establish a lasting presence along the coast north of present-day Florida. As a man invested in and employed by the Plymouth Company, Davis may have been motivated by corporate greed. Once exposed by Percy he had little choice but to lift his hand to help the colonists in James Citte. He may well have been an early example in American history of a man who put corporate wealth ahead of country.

Any help Davis could provide was too little too late. The village of 500 had been decimated. The few remaining Virginia Colonists were beyond discouraged. When producers from the television show, The Walking Dead, arrived in Jamestown to audition the surviving colonists for a reality television series, they described the survivors as looking too realistic and brought in actors from a theater guild for filming. Okay that was my bad stab at a metaphor.

“This is bull shite,” mumbled one of the starving as he fried the only rat he could find over an open pit fire. “We are out of mayo!” Percy had heard enough. He decided to embark for England where, at the very least, they would find a good Hollandaise Sauce.

Percy understood the situation. It was time to throw in the towel, board the ships available and head back home to England. The experiment or whatever the hell Jamestown was, was over. Sure, corporate stakeholders would be livid to learn that he had returned to London with every Jamestown resident who ever boiled a rat or ate dirt. But the fat cats of Fleet Street had not had their boots on the ground in Jamestown to see the tragedy unfold each day.

Corporate offices were engaged in financing efforts on at least two fronts. Jamestown was a lesser problem as England engaged in the 43rd year of an Eighty Years War involving Spain in the Netherlands. They were distracted from their endeavors in Virginia by the need to protect their home front. It wasn’t that they had forgotten Jamestown, it was simply that they had chosen to ignore the colony. It wasn’t considered safe to put British ships on the high seas when Dutch and Spanish pirates and naval vessels were fully engaged in warfare that threatened the English.

Percy’s account of what was to be his last day in Jamestown reveals a crazy turn of events:

“Then all of us embarking… Sir Thomas Gates in the Deliverance with his company, Sir George Somers in the Patience, Percy in the Discoverie, and Captain James Davis in the Virginia. All of us sailing down the river with full intent to proceed upon our voyage for England when suddenly we spied a boat making toward us wherein we found Captain Bruster sent from my Lorde de la Ware (Lord Delaware) who was come unto us with many gentlemen of quality, and three hundred men besides great store of victuals, munitions and other provisions; whereupon we all returned to Jamestown.”

Talk about a simple twist of fate. Percy’s four vessels were just a few nautical miles from the open sea, heading home to England in the last bit of the James River Estuary when he encountered one of three ships sent by the British to Jamestown. Lord de la Ware was arriving with the supplies needed to survive in Jamestown. Not only did de la Ware bring the necessary food and staple items, but he was transporting 300 more settlers, including 150 armed soldiers. Percy gave thanks to a god that grants white men the right to kill people and turned his ships around. The colonists headed back up the James River to a fort that had been left to rot and decay. It marked a turning point in British colonial history. We are not told how many of the surviving residents were happy with that outcome. Some historians believe Percy reluctantly followed orders.

Lord de la Ware replaced Captain Smith and Percy as the ‘governor’ of the colony. He quickly engaged in a scorched earth policy, eradicating Native villages, destroying their crops and communities. It was a strategy he had employed as a commander in Ireland. James Davis felt right at home with de la Ware’s leadership. Lord de la Ware was the title given to a man otherwise named Thomas West (1577-1618). Americans turned his titled name into Delaware and plastered his surname on rivers, bays, a Native tribe and an entire state. Things got out of hand when the people of that state identified the Mud Hen as the mascot for their college.

The growth of pioneer communities continued to alarm Powhatan, chief of the Tsenacommacah. Ironically, prior to the arrival of the European, the term ‘Tsenacommacah’ meant densely inhabited land. There were numerous populated villages along the eastern shore and it is believed that the American continents (North and South) had a greater population than the entire European continent. Various diseases, foreign to the Natives, including smallpox, wiped out as much as 90 percent of the Native civilization, prior to the white guy’s arrival. In response to the pressure brought by the Anglo pioneers, Powhatan retreated further up-stream and into the wilderness. But the Europeans kept coming further inland.

“It is like osmosis,” Powhatan explained to his children as they scavenged for clams. “The Whites have settled into this one little spot of land and pretty soon they are going to litter our world with plastic bottles, fast food joints and country music venues. Maybe not in my lifetime, but sure as hell, it will happen and soon enough. I frickin’ guarantee it!”

“What can we do daddy?” One concerned child asked.

“Just one word of advice,” the father whispered, “plastics.”

America was moving forward.

James Davis chilled out in his later years and settled into a plantation home along the James River. King James of England was granting large tracts of land to the upper crust of Jamestown and to new arrivals who were developing plantations which would nurture and grow tobacco. One of my wife’s great grandfathers, Henry Southy, was one such planter. The Baileys in our Smith tree were also among the first planters to engage in the tobacco trade. My wife’s Whittingtons, Littletons, Scarboroughs, and my Smiths, Taylors and Preslys would soon follow.

The British were using a plantation system in Ireland as a strategy for eliminating an Irish Catholic population. It was a model developed by Sir Humphrey Gilbert, the same Humphrey who met his demise while reading Paradise Lost on the deck of the Squirrel. They established plantations in Virginia and eradicated the Natives, pushing them off their lands. In the centuries that followed the great Sioux chief, Spotted Tail, would comment on the history of his people:

“This war did not spring up on our land, this war was brought upon us by the children of the Great Father who came to take our land without a price, and who, in our land, do a great many evil things… This war has come from robbery, from the stealing of our land.”

Chief Justice John Marshall, long recognized as the rock star of our federal Supreme Court and a nephew to Martha Smith, Peter of Westmoreland’s daughter made this callous observation:

“The tribes of Indians inhabiting this country were fierce savages, whose occupation was war, and whose subsistence was drawn chiefly from the forest… That law which regulates, and ought to regulate in general, the relations between the conqueror and conquered was incapable of application to a people under such circumstances… Discovery gave an exclusive right to extinguish the Indian title of occupancy, either by purchase or by conquest.”

And no less a scholar than President Andrew Jackson, whose portrait embraces the eyes of President Trump each day in the Oval Office, once astutely observed:

“They have neither the intelligence, the industry, the moral habits, nor the desire of improvement which are essential to any favorable change in their condition. Established in the midst of another and a superior race, and without appreciating the causes of their inferiority or seeking to control them, they must necessarily yield to the force of circumstances and ere long disappear.”

Unable to work in collaboration with the Natives and in conjunction with Nature the newcomers to the New World pillaged not only the Native people they encountered, but the land as well.

Tobacco became the cash crop and the currency in this new world market. Efforts would eventually require a large labor force with the burden of that work falling on the backs of indentured servants from Ireland and slaves brought in chains from Africa. It was the beginning of an era in world history that would change forever the culture of the new world.

Amidst all his adventures, James Davis married Rachell Keyes and together they raised their children on the shores of the James River and in the schools of England. Places like Henrico, Nansemond and Albemarle, as well as a home in England, would become prominent locations that housed James Davis and hisdescendants.

At the time of his death in 1618 Powhatan had shown little desire to wage war. His younger brother Opchanacanough became CEO of the Algonquin Nations of Virginia. He met fire with fire. In his first board meeting with the tribal council I would imagine the new ruler utilized a PowerPoint presentation to explain his intent to apply Newton’s Three Law of Motion to triumph over the Europeans.

“The First Law my brothers is this: Objects will remain in their state of motion unless a force acts to change the motion. These damn crackers are going to keep coming up the river unless we act to change that! We must dislodge them. Are you feelin’ me?”

“The Second Law: the velocity of an object changes when it is subjected to an external force. We are the external force. The speed with which these guys are moving into our nation must be met by our use of tremendous force. We must stop their momentum by meeting them head on. Can I get an ‘Amen?”

“And finally, the Third Law, and this is my favorite my brothers, ‘For every action (force) in nature there is an equal and opposite reaction.’ We have to nail these Anglo butts to the ground. This is our house. No one comes into our house and disrespects us!”

“Now! Give me a ’T’!”

Opchanacanough then launched into the first use on North American soil of the storied cheer used at every sporting event ever witnessed in America. He eventually stumbled through the spelling of ‘Tsenacommacah,’ and lathered up his warriors for war. When he finally ended the spelling with the letter ‘h’ and asked, “What does that spell?” His audience had forgotten the first few letters and shouted “Macah!” Thus, years later, the tribal school organized their first lacrosse team as the ‘Fighting Macaws.’ Not true.

Opchanacanough stepped up the pressure on the James River valley communities and plotted the eradication of Jamestown and surrounding villages. For the second time in a decade, the population of the colony was nearly wiped out. This time in what could only be described as an act of genocide that nearly succeeded.

James and Rachel Davis, as well as their children, survived the Jamestown Massacre of 1622. Henry Southy, Nancy’s 10th great grandfather, and several of his children did not survive. The James Davis family was not listed among the hundreds that were slaughtered. Nor were they listed on the roll call sheet of the survivors. It is believed that the Davis family had been in England at the time of the massacre. James Davis died somewhere between 1622 and 1633. The smart money in Vegas is on 1623. A Virginia historian of the time, James Hotten, wrote as follows: “James Davis, dead at his plantation over the water from James City on February 16, 1623.” ‘Over the water’ implied that James died on the south side of the James River. That would put him in what today would be Isle of Wight, Surry or Nansemond County.