The Descendants of James and Rachell Keyes Davis

From the south side of the James River in 1623 to the pocosin swampland of the Pungo River in Hyde County in 1802 was a journey of 179 miles and 179 years. I have traced the lives of countless numbers of Davis offspring into the hills of Kentucky, the cornfields of Illinois and swampland of the Carolinas. I have encountered kidnappings, massacres, plantations, fortifications, acts of fornication and a man who got his father drunk and stole his land and business right out from under his hand while the ink was still drying on the parchment.

Sorting through all of this is a story in itself. No one has ever made this journey before, not on paper anyway, or in Cyberland. There is no previous record identifying the ancestors of William Davis, Esq. I am carving out a storyline that hasn’t been written before. Characters will come and go; some will become great grandparents, while everyone else becomes a cousin, great aunt or uncle. I apologize in advance for the confusion that is about to ensue. This is what it looks like when a ‘family historian’ stumbles into the Goridan Knot of ancestors for the first time. Keep in mind my credentials: a college degree in history, a doctorate in research and then there is the Irish storyteller in me, confounding the matter. I will try to do this justice.

The children of James and Rachell Keyes Davis are not easily identified. The first of their children were born and raised in Britain. Birth records are not available. Male children of colonial aristocrats were often raised in households in Great Britain, tutored by scholars, and attended elite academic institutions. I have consumed large quantities of time and beverages pursuing these rascals. While I am good at tracking them and have Ninja type skills (like Napoleon Dynamite), I admit some trepidation with my findings. I reserve my right to be wrong.

James (1575-1623) and Rachell Davis (1580-1633) of Jamestown had several sons: Thomas, John, Samuel, William and Richard. Future DNA testing will add definition. Families migrated per the usual patterns found in Colonial Virginia. The deeds they authored marked the trails each man traveled. Davis pioneers moved in one of three directions: 1) north from Jamestown into the Rappahannock Basin and Somerset County, MD; 2) west, a tad bit upstream on the James River toward Richmond, and 3) south, deeper into Nansemond, Isle of Wight and eventually the Carolinas. There were other means of escape from Virginia. One could hop on a boat back to England, or north to Boston or Philly. One could also enjoy a cruise ship voyage to Barbados and

“Stay 6 days and 5 nights at the Fairmont Royal Pavilion, Barbados’ the only all-inclusive luxury hotel on the Platinum Coast directly on the beach.” —This ad paid for by Friends of Barbados.

Route 1

The Rappahannock region was first settled by my 8th great step-grandfather, John Mottram, who violated British law by locating his double wide on land the Brits preferred to respect as Native land in 1645. That policy all changed when the British preferred to settle those same lands in 1682 and ceremoniously did what Brits did back in the day: ignore agreements with the tribal nations, expel the tribes and move in. When the tribes objected and reminded the British of their previous commitment, the Brits demurred and responded with their usual aplomb:

“Well, that was then. This is now. We have to live in the moment.”

The British Governor Culpepper then handed the tribal CEO a complete collection of the works of Eckhart Tolle and recommended a short course at the local junior college titled Living in the Now. In November of 1682 the governor’s Council laid out 3,474 acres (5 square miles) for the Rappahannock tribe in Indian Neck, “about the town where they dwelt,” but the General Assembly forced the tribal members from their new homes one year later in response to increasing attacks by the Iroquois of New York. As a side note in family history: my wife Nancy’s 8th great grandparent Southy Littleton represented Virginia as the colony’s commissioner at the Conference with the Iroquois Confederation in Albany NY. He was trying to orchestrate a peace treaty with the Iroquois when a heart attack caught up with him and ended his life.

Charters were granted to fat cat cronies of the monarch and those fat cat crony types (guys like Culpepper) sold patents of land to speculators who then hired surveyors who marked trees the way a dog could only do, and we soon had deeds that read like the Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Trees.

Route 2

In the second route of migration out of Virginia: ancestors who headed west followed the course of the James, Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers, settling close to those navigable rivers and their tributaries. Once reaching the fall line our pioneers trekked uphill on the worn paths of generations of Natives or constructed new pathways through the foothills of the Appalachian and Allegheny Mountains. But that was a century and several generations beyond 1638.

When the time came to breach the Blue Ridge, it would be a bit like traveling out of Virginia on Interstate 64 or state highway 17, just a bit more scenic back in the day. Pioneers, including our own ancestors, filtered into the Ohio River Valley or southwesterly along the earliest of American superhighways, the Great Wagon Road. Wagons and carts leaving Philadelphia would pay a toll at Nancy’s 6x great grandfather Slaymaker’s toll station in White Chimneys PA. They might even stay the night at the Slaymaker’s inn and down one of the family home brews.

Early pioneers gained fame by rearranging the trees along a pathway the Native Americans used for centuries as hunting trails. Our family members clambered up and down Uncle Bailey Smith’s Wilderness Road in the 18th Century, looking for decent truck stops, roadside lodging and a plot of ground on which they could harvest locally sourced grains, vegetables and meats. Davis families clustered in enclaves in Kentucky, Ohio and Indiana. These included the Davis family members whose lives were destroyed in the Great Massacre at Fort Kincheloe. I shouldn’t get ahead of myself. I need to focus attention on 17th Century ancestors who lived within a 50-mile radius of Jamestown, or I will never get these guys into the correct knothole of our family tree.

Route 3

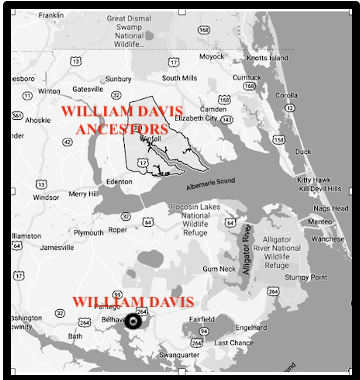

The third migration of ancestors, those who ebbed south into Nansemond County, Isle of Wight and the Carolinas will eventually lead us to William Davis Esq, my father’s 4x Great Grandfather from whom I descend. He fathered Sarah Davis. She married Hezekiah Stilley and they moved to Southern Illinois. It was there that the Stilleys claimed squatter’s rights in what was still considered Indian Country. It was there that Jane Stilley would be born and eventually give birth to Grampa Leb Smith. I sometimes wonder if William Davis Esq ever saw his daughter Sarah again, after she and Hezekiah headed away from the shores of Pantego Creek. I have found numerous family letters of that era that indicate, ‘No,’ the distance was often too much to bridge.

So, the question arises: How did these half-crazed ancestors get from Captain James Davis’s prime spot for a seafood restaurant at Fort Algernon, VA to a tobacco plantation on Pantego Creek in Hyde County NC? To answer the question, I had to drain the Carolina archives of any abstracts, wills, deeds and documents that might reveal clues. I found myself in a time warp, caught up in rebellions, religious strife, political intrigue, executions, privateering, piracy, treason and the rites of passage a nation must survive to inaugurate a westward movement.

Each deed and will uncovered a name that would eventually appear in our family tree as a cousin, uncle, aunt and grandparent. It was the grandparents I wanted to locate. I wanted to find their darn DNA. In this swirl of activity in the 1600s I kept finding ancestors playing strategic roles in history, and often in conflict with one another, and quite frankly it got fascinating. I will now introduce a cast of characters, suspects in the Case of the Missing Grandparents. We will weed through them together and establish their place in our family tree.

Editor’s Command, (Speaking to Wilbur Rancidbatch, who was sharing one of his concoctions with our guests): “Bring in the first one: Major Thomas Davis!”

Gen 13: Major Thomas Davis (1613-1683)

Son of James Keyes and Rachell Keyes, Chuckatuck VA

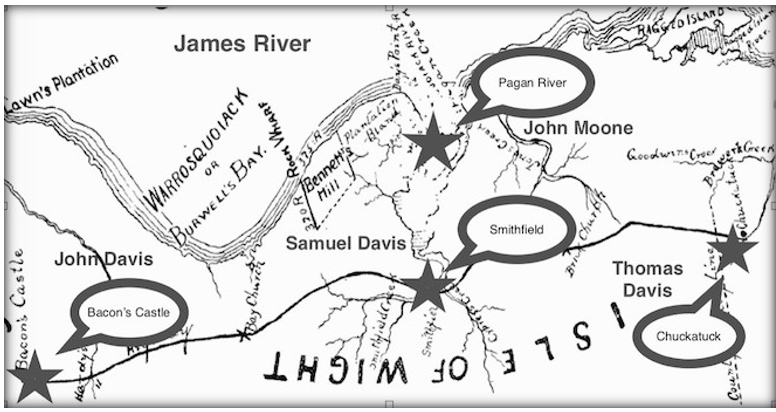

This son of Captain James Davis and Rachell Keyes, was born in 1613. An affidavit in the Admiralty Court in London in 1639 was made by Thomas Davis, born 1613, son of Captain James Davis, in which he stated he was ‘A Merchant of Chuckatuck in Virginia, aged 26 years.’ Chuckatuck appears as a creek feeding into the south side of the James River Estuary on the previous colonial period map.

Thomas, a merchant and planter, was one of the first settlers on Herring Creek. He maintained several plantations in addition to his father’s original plantation on the south shore of the James River in Nansemond. In the decade after the 1622 Jamestown Massacre the colonists gained courage and pushed inland along the James River. Reinforced by population growth, military force and avarice, the colony spread to the south and west of the original site of James Citte.

Thomas Davis was recognized in documents as

“the son of James and Rachel Davis, late of Henrico, in Virginia deceased, granted 300 acres of land on Warricksqueake Creek, 100 acres in right of his father, an ancient planter, who came to Virginia in the George 1617, and 100 acres in right of his mother Rachel, wife of said James. March 6, 1633.“

This deed identified James and Rachell as late of Henrico, which put them in a region adjacent to present day Richmond. It identified them as “Ancient Planters.” British law recognized the first settlers who had survived the 1607-1617 as “Ancient Planters.” The term ‘ancient’ simply meant ‘original’ or ‘first.’ It had nothing to do with age. Each ‘Ancient Planter’ received 100 acres. The reference to the Davis arrival on the George is misleading. It implied that it was a first appearance in Virginia. The family was well versed in sea travel and made frequent trips across the ocean to and from England. When Rachell first arrived and if she remained is subject to speculation.

When the law allowing acreage to Ancient Planters came into play James and Rachel Davis were deceased and son Thomas was entitled to their property. On March 6, 1633, he garnered 300 acres, acquiring an additional 100 acres as a head-right claim for transporting George Cocke and Alice Mullins who arrived on the George in 1617.

A 1636 transaction finds Thomas engaged in a sale to Ambrose Meador:

“Thomas Davis of Warwicksquacyk to Ambrose Meador and John White of the Pagan Shore, 50 acres of land lying in Warwicksqueake, beginning at upper Red Point and extending easterly down the said Creek, was given said Davis by patent 6 day of March 1633, the land abutting northerly upon said creek and southerly into the main woods, 18 July 1636.”

Thomas sold a parcel of the 300 acres of land that he had acquired in 1633. The surnames Meador and White appear frequently in our family tree. My software just identified 106 of them hiding in the computer (our online family tree). Twelve of those folks are named ‘John White.’ The surname Meador was frequently shortened to Meade, Mead and Meed. Ambrose Meador may lead to Susannah Meed.

In a flurry of activity in 1637, Thomas Davis engaged in transactions involving

• 300 acres in Nansemond upon the south side of East branch of Elizabeth River,

• 100 acres on Oyster Bank Neck, in the Isle of Wight,

• 100 acres adjacent to Thomas Jordan and Richard Bennett, and

• 600 acres, on the Bay behind Ambrose (Meador) Point

With only 2,500 people estimated to be living in Virginia in 1630, it is not unusual to find surnames of early survivors, decades later, in a family history. With each deed that surfaces I find buyers, sellers, witnesses and legatees whose names appear in our pedigree charts. Thomas Jordan is one example found in the above transactions. Thomas was the son of my father’s eighth great uncle, Samuel Jordan, of Beggars Bush, one of the first settlers in Jamestown Colony.

In 1648 Thomas Davis sold 200 acres to John Moone, a very wealthy land baron with family ties to the Greens and Davis families that will occupy a place on our stage in the next generation. At the time that I first wrote this paragraph, John Moone’s position in our family tree was not yet clear. As of April 2018, he has been identified as my father’s 10th great grandfather.

John Moone is listed as a landowner in the above ‘notice.’ Richard Wilkinson is a step grandfather in our tree and John Flyne’s children sold Hyde County NC land to the William Davis family in the mid-18th Century.

These are just a few of the land acquisitions involving Thomas Davis in the years 1635 through 1675. While the deeds are too numerous to mention, it is helpful to note the many locations in which he prospered: Newton, Haven River, Beverly Creek, eastern branch of Elizabeth River, Pagan Creek, Warrasquiack Creek, and Oyster Creek Bank and eventually Somerset County, Maryland. His growing empire covered a range of 100 miles from north to south.

Methods of communication and transportation were not what they are today. Men on horseback and in shallops ruled the day. The entire European continent had been structured politically and economically in much the same manner: Small principalities became shires and counties and organized into larger countries over time.

Hoping to learn more about the immediate family of Thomas Davis, I scoured the deeds and jotted down the names of locations, neighbors and witnesses. Thomas filed a deposition in Norfolk Co, Virginia in 1640 which revealed his wife’s name.

“sold a grant from Sir William Berkeley June 1, 1649, to Thomas Maros, who sold said land 400 acres unto Robert Bowers, who in like manner gave the land to his daughter Mary, wife of Thomas Davis, and was conveyed by them November 14, 1708, unto Phillip Reynolds, Merchant, ‘lying on west side of Western Branch,’ in which deed Thomas Davis is styled, of Nansemond Co. planter”

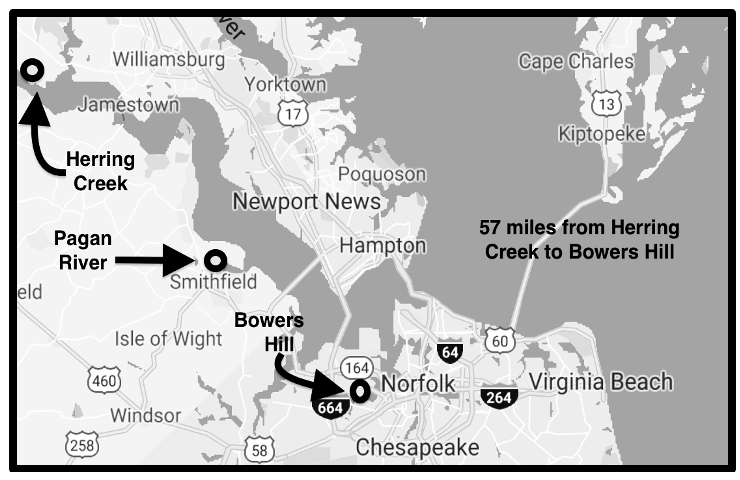

Within this deposition we find the name of Mary Bowers, identified as a “wife of Thomas Davis.” The 400 acres of land began as a patent doled out by Governor William Berkeley in 1649. Thomas Maros held possession at one time, sold it to Robert Bowers who then gave the property to his daughter, Mary. The description of the land allows a clever man, armed with Google Earth, the opportunity to pinpoint the property on the Nansemond backwater. In the following screenshot I have identified Bowers Hill. The site is being explored, in 2018, as a perfect location for “a futuristic high-speed rail station.” I have penciled in several of the sites in which Thomas owned properties.

The James River Estuary of Thomas Davis

The above image shows the far-flung properties of Thomas Davis located in Herring Creek to the northwest of Jamestown to Pagan River and Bowers Hill to the southeast.

Online research indicates that Thomas may have acquired a second wife along the way. The name Elizabeth Christian is found in many family trees and some credit her with giving birth to all the Thomas Davis children. The children of Thomas included: Mary (1640-1689), James (1642-1688), William (1643-1680), Richard (1645-1697), Sarah (1660-1712), Thomas and Samuel. I am not sure which mother should be assigned parenting rights to any or all, of these children. I fear one or the other woman could assault me in my sleep and leave me addle minded in the morning should I get it wrong. If you have ever heard a cow bellow when separated from her calf, you know what I am talking about.

Author’s Command: “Bring in another suspect! Who do we have here?”

Editor’s Response: “This is Samuel Davis, Senior, looking well healed despite the perilous journey over the Atlantic.”

Author: “Well healed? Look at the man. He needs a shave, a good bath and a meal or two. He looks like he just got off the boat…”

Gen 13: Samuel Davis Sr (1610 – 1667) and Elizabeth Benton

Samuel Davis Sr was one of several Davis brothers to who arrived in Jamestown from London, England on July 6, 1635, aboard the ship Paule. The Master of the ship, Leonard Betts, knew all three of these young men on the voyage across the Atlantic. Samuel, the oldest, and his brothers, John (age 23) and Richard (age 20) were identified on the ship’s manifest of 115 immigrants.

Samuel arrived in Virginia at the age of 25, with his wife Elizabeth Benton and first-born son, Samuel Davis, Jr (1631-1687). The expense of Samuel’s passage and that of his wife and child was covered by Elizabeth’s father, John Benton, a well to do businessman who had first arrived in the colony seven years earlier.

The passengers of the Paule each received a certificate from the Minister of Gravesend, England, assuring the folks in Virginia that these guys conformed to the Church of England. This was important in the England of 1635. Archbishop Laud was persecuting non-conforming Brits, those who might be Puritans, Separatists, Presbyterians or members of the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster, for that matter. There was a room in the cell block of the Tower of London reserved for those who refused to conform and a graveyard out back that would gladly receive the bones of any dissident who failed to repent and agree with the Archbishop’s worldview.

Each of the three brothers signed the paperwork in Gravesend, England, attesting to the fact that he was one happy supporter of the King’s Anglican Church. I have read enough of these documents to know that people signed the paperwork less out of passion for the King’s church and more often to simply save their necks and avoid the Star Chamber and Tower of London.

I can picture the scene: These guys were cued up on a dock in Gravesend, England, ready to board the ship Paule, for America. A squatty little codger smelling of alewife and cod ran a quill pen up each nose, scowled, and said, “Sign here if you love the King’s Jesus and want to get on board this ship.” I know I would sign the paper AND share it on Facebook.

A certificate of conformity issued in Gravesend was by no means evidence that the Davis men were from Gravesend, it meant only that Gravesend was their point of departure for the voyage to Virginia, a bit like going through a TSA checkpoint at O’Hare Airport. Many family historians error in assuming Gravesend was their hometown.

All three Davis brothers initially lived in Charles River County VA. Having paid for the transport of immigrants Mr. Benton was entitled to 1250 acres of land described as “15 miles up along the south side of the Rappahannock River.” The deed was posted October 13, 1642, seven years after the 1635 family arrival in Virginia. Gathering head rights was like collecting SkyMiles today. A person recorded the passengers they sponsored on the day of their arrival and cashed in the receipts as needed.

Samuel Sr assigned 400 of his acres to John Benton as payment to Benton for covering the initial costs of Samuel and his wife and son’s transport to Virginia. While brother John Davis remained in Charles River for the moment, brothers Richard and Samuel Davis each moved south, crossing the James Estuary into Isle of Wight County.

Samuel Senior’s name first appears in the records of Virginia on October 4, 1640. On that date “Sir Francis Wyatt grants to Samuel Davis 100 acres on a branch of Pagan Creek, adjoining Nathaniel Floyd,” in Isle of Wight County. The Floyd name appears in our family tree. Hezekiah Stilley’s grandfather John Andersson Stille (1683-1774), married Mary Floyd (1688-1774) in Isle of Wight. Mary is my 6th great grandmother and found in the Stille branch of our tree. Small world? Yes, but the population was growing. It is estimated that there were 75,000 citizens in the colony in 1710. Add another 25,000 slaves and you have a population of 100,000 people, comparable to Green Bay WI and vicinity on any day other than a Packer home game day, when you can add another 80,000. I digress.

When you only have 2,500 people living in an area as did Virginia in 1630, folks are bound to be intermarried, intermingled and interloping. In 1710 I am less certain that Mary descended from Nathaniel Floyd or if they are related at all. The population growth in Virginia following the Civil War in England and unrest in Europe changed the social dynamics in Virginia and the colonies in general. Honestly, I haven’t the time to research the Floyd links. I am leaving Nathaniel Floyd alone. He can haunt me in my sleep if he wants to.

The population within Isle of Wight County was growing and the congregation of the church and wealth of Samuel’s neighborhood could support a second Anglican church. For that reason, in June of 1642, Isle of Wight County was divided into two parishes, the Upper and the Lower Parish. The boundary between the two parishes was created at the Lawne’s Creek plantation of Samuel Davis, Sr. He operated two plantations throughout his lifetime: Lawnes Creek and Southwarke in Isle of Wight and Surry County. He and Elizabeth had two sons that we know of: the aforementioned Samuel Jr and a second son: John Davis (1635-1712).

Gen 13: John Davis (1612-1688)

John Davis (b 1612) was the second of the three brothers to step off the Paule in 1635. He was an uncle to Samuel Jr (b 1631) and John Davis (b 1635). I spent considerable time exploring what little I could find in his resume. Hiding innocently enough in a book of deeds I found a document that proved to be the tip of an iceberg and one of the most provocative stories in our family tree and nation’s history.

On August 15, 1637 John Davis secured a patent for 300 acres on “a great swamp.” The land was characterized by a long meadow that stretched between two forests and therefore became known as Longfields. He added an additional 300 acres for head rights on 6 persons for whom he provided transport to Virginia.

John Davis hung on to this property for much of his life. He sold Longfields to John Coxe in 1665, and Coxe assigned Longfields to John Burton, husband of Mary Coxe Burton. Longfields was destined to become the home of one of the most controversial icons in colonial history: Nathaniel Bacon of Bacon’s Rebellion. Our family’s entanglement with Bacon involved more than the plantation and nearly cost three of our clan their lives when charged with treason by Governor Berkeley.

John Davis died in 1688. The abstract for his will reads as follows:

“John Davis of Perquimans died April 26, 1688. His wife Elizabeth, John Pritchard, friend Wm Wilkinson in trust of my daughter Elizabeth; Wm Wilkinson executor, Matthew Jorlyes, Wm Elfirk, Jane Miller.”

John Davis was survived by one daughter and one wife, each named Elizabeth. There appears to be no son who predeceased him or grandson carrying the name forward from his home, nor would Elizabeth become a grandmother to our William Davis Esquire. But within that abstract there is one very helpful clue. John Davis (b 1812) had a best friend, a man so close and trusted, that Davis asked him to be the guardian to his daughter Elizabeth. That man, ‘Wm Wilkinson,’ was named the executor of his will. Davis and Wilkinson were close. Future generations of Davis and Wilkinson offspring formed a tight knit community in Hyde County circa 1750-1850.

As the author of this growing melodrama I have had the luxury of reading ahead. I have had my history books open and I know what happens next! The plot thickens. The roles our ancestors played in Carolina history was critical to the early development of the colony and country. John Davis and William Wilkinson were major players in Carolina history. The question remains, in what part of our tree did they build their nests?

Gen 12: Samuel Davis, Jr (1631-1687)

Son of Samuel Sr and Elizabeth Benton

Samuel Jr obtained a grant of 950 acres in Albemarle (Carolina) for the transportation of nineteen persons into the colonies. The land he acquired was frontage on the north side of Albemarle Sound, adjacent to a swamp. In 1668 Samuel Jr acted as executor for his father’s estate in the Isle of Wight VA. Junior was committed to staying on his Carolina estate and divested himself of his father’s plantation in Virginia. He deeded a tract of his father’s Virginia property to his brother, John Davis of Isle of Wight County. That land was first purchased by Samuel’s father (Samuel Sr, the Paule immigrant) on June 11, 1642. Samuel Davis Jr also sold 100 acres of Isle of Wight land to a John Bond who married one of the Davis women, Sarah. Junior was committed to living in Albemarle, later to be known as Carolana, then Carolina and eventually, in the days of the Revolutionary War, North Carolina. That would be long after Samuel Junior’s death in 1687.

Junior’s life is revealed in snippets taken from court cases in the the 17th Century. A glimpse into Junior’s life is revealed in an affidavit filed by our second cousin, Henry White (1642-1712) in the year 1697. Samuel Junior had been dead for a decade but his will was still the subject of family debate. Samuel’s daughter, Alice Bilett, charged that Junior’s son and her brother, Samuel Davis III, had wrongfully denied her access to property her father intended for her.

Henry White was called into court as a family friend who could establish the identities of the various plaintiffs, defendants and parents in this family drama. Henry gave his own age as 57 at the time of his court appearance in 1697.

Henry White declared:

“that he knew Samuel Davis (Jr) deceased (in 1688) that lived in the precinct of Pascotank in this Government and that he knew the said Samuel Davis (Jr) when he lived in the Isle of Wight as an Apprentice to his Father Henry White of the Isle of Wight County afsd Cooper and that after he was out of his time he married one Ann a servant to Captain James Blount and afterwards about the year 1660 the sd Samuel (Jr) and Ann, his wife, removed themselves unto this Government where the Deponent knew them to live several years and had several children and that Samuel Davis III who now inherits his father’s Land in Pascotank is the Eldest Son of Samuel (Jr) and Ann Davis deceased.”

The lives of the Henry White family are inextricably interwoven with the lives of various members of the extended Davis family. Again, when you have a small population in the region in the 1600s lives are going to be, by necessity, inextricably interwoven. Say that three times.

Henry White’s father (also named Henry, 1615-1670) was a cooper, (barrel/cask maker), in the Isle of Wight County VA. Samuel Davis Jr (b 1631) served an apprenticeship learning the trade from Henry Sr and when he had ‘put in his time,’ Samuel Davis Jr married Ann, a servant in the Blount manor house. Henry White (b 1642) pointed out that Samuel Jr had moved into Albemarle in 1660. This information is of historical importance. Samuel Davis Junior was one of the first European settlers to enter and remain in Carolina. His arrival predated the establishment of Roger Williams’ 1663 patent and prior to George Durant’s homestead (1662). Williams and DuDurant are often cited as the first to settle Albemarle (Carolina). Samuel Davis preceded them.

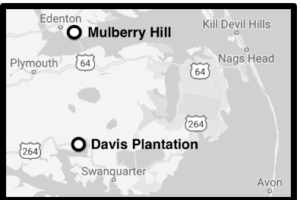

In 1684, Captain James Blount (1620-1686) in whose home Ann worked as a servant, bought 660 acres on the north side of the Albemarle Estuary and established Mulberry Hill plantation. His sons added 200 acres in 1697 on Pocosin Creek, a tributary of the Mattacomack River. Modern man turned the plantation into an 18-hole golf course and a terminal for the Northeastern Regional Airport of greater Edenton NC.

In 1684, Captain James Blount (1620-1686) in whose home Ann worked as a servant, bought 660 acres on the north side of the Albemarle Estuary and established Mulberry Hill plantation. His sons added 200 acres in 1697 on Pocosin Creek, a tributary of the Mattacomack River. Modern man turned the plantation into an 18-hole golf course and a terminal for the Northeastern Regional Airport of greater Edenton NC.

Established in 1962, The Links promotional piece reads:

“Welcome to The Links at Mulberry Hill, your top option for a round of golf in Edenton, North Carolina…a semi-private country club located on Albemarle Sound in historic Edenton. Just seven miles from the heart of Edenton, The Links shares a rich heritage with the prettiest town in the South.” –This ad paid for by Friends of The Links at Mulberry Hill

Get my clubs. I think I need to stake my claim to a family heritage site. Blount is the second in our family who hunkered down on property that became a fine country club offering southern hospitality and a scenic and challenging round of golf. James Blount is a second cousin. His son John Blount (1669-1724) married Elizabeth Davis (1679-1732). Elizabeth was the daughter of John Davis (1648-1720) and Mary Burton (1652-1696).

Henry White of Albemarle (1642-1712) was a stalwart of the Quaker Church in Carolina, a founding father of several meeting houses in Albemarle, a renown poet and well respected. He was the father of Elizabeth White (1673-1748). She married James Davis (1668-1716), also a Quaker. James was the son of William Davis (1643-1680), grandson of Captain Thomas Davis (1613-1683) and the great grandson of Captain James and Rachell Davis, Ancient Planters of Jamestown VA. DNA results have confirmed these links.

The generations that descend from the union of James (1668-1716) and Elizabeth White Davis provide fascinating stories related to southern plantation life over the course of two centuries. Their son, William Davis (1692-1756), of Davis Island, North Carolina, lived the plantation life on the Outer Banks. His family history would make an incredible documentary. I have incorporated some of these tales (appended in this volume).

We are now accumulating shirt tail relatives and neighbors at an alarming rate. They accompany our direct line of ancestors through time and space. They formed a support group in terms of business relationships, religious affiliation and social life. If Earth is our spaceship, traveling through the cosmos and we are all astronauts, these ancestors were characters who played an integral role in our survival and our very lives today. Without them, there would be no box of Cheerios on the kitchen counter, no Kriha’s Farm Pure Wisconsin Maple Syrup.

“Wisconsin Maple has been a standard by which all syrups are judged. You can taste the pursuit of excellence in Kriha Farm products. The syrup is 100% pure and natural sweetener rich in minerals.” — This ad paid for by Friends of Kriha Farm, Birnamwood WI.

Editor’s Command: “Who’s next?”

Author’s Response: “John Davis.”

Editor: “Which John Davis?” (Pause)

Author’s Response: “Bring in John Davis, the brother of Samuel Junior whose father Samuel Senior came to Virginia on the ship Paule.”

Editor: (turning to a room full of visitors who appear dressed for a Jimmy Buffet concert) Are you the John Davis Junior whose father, Samuel, arrived on the Paule in 1635?

John Davis: “I am. Those are my uncles over there in the corner, Richard and John, eating shellfish and playing snooker. My father Samuel is at the racetrack today, running his horses.

Editor: “You are quite the specimen. How long have you been dead?”

John Davis: “I don’t know. What year is this?”

Editor: “I am writing this bit in 2018.”

John Davis: “Seriously? Give me a moment to digest that.”

Editor: “The years?”

John Davis: “No, that plate of ham. Is that a Smithfield Ham? Looks awfully good.”

Editor: “Bugger off! This is Nueske country, mate.”

Gen 12: John Davis (1635-1714)

Son of Samuel Sr and Elizabeth Benton

This second son of Samuel Davis Sr married Mary Green, daughter of Thomas Green and Mary Moone. Mary Moone was the daughter of John Moon (aka: Moone), one of the early settlers in the Isle of Wight and a very wealthy man. John Moone owned land and houses on Pagan Creek in Isle of Wight County. In 1648, Moone purchased 200 acres from Thomas Davis of Nansemond. I pointed Moone out to you earlier. He was the guy riding a Harley and drinking Woodford Reserve Doublewood Bourbon on the dirt path leading from Pagan Creek to Smithfield.

On the last day of June in 1664, John Davis (b 1633) acquired 200 acres, beginning at a point of land called the Goatpen neck, at the mouth of Taberer’s creek. In 1668, he received 100 acres on a branch of Pagan Creek, in Isle of Wight. The property was near the present-day city of Smithfield. This tract of land was his share of his father’s estate as assigned to him by his brother Samuel Jr in 1668 shortly after the death of Samuel, Sr.

The village of Smithfield, first colonized in 1634, is located on the Pagan River, south of Jamestown and on the south side of the James River. The Native Americans knew this area as Warascoyak, also spelled Warrosquoyacke, meaning “point of land.” The Virginia colony officially formed Warrosquyoake Shire (with numerous variant spellings, including Warrascoyack, Warrascocke and “Warwick Squeak”) in 1634, but it had already been known as “Warascoyack County” before this.

Davis Plantations on Warrosquoiack of the James River

It was renamed as Isle of Wight County in 1637. People got tired of trying to spell the Native name for the area and the Native population grew weary of hearing the Europeans butchering their native tongue.

In July of 1665, a John Marshall purchased 700 acres on ‘Wester Swamp.’ A decade later John Davis and John Marshall were pleading for their lives as participants in Bacon’s Rebellion (1676). Governor Berkeley hanged 23 of their compatriots in the public square to make his point that an act of treason is not a good way to resolve a problem. Marshall groveled in the dirt on bended knees to save his arse. John Davis and his cousin Richard Jordan were spared the death penalty. The details are recorded in the annals of the William and Mary College Quarterly.

Nathaniel Bacon, not related to Nueske Bacon, was born into wealth in Suffolk, England in 1647. He was not a yeoman or commoner. He was Cambridge educated and came to Virginia as a young adult male with a substantial amount of cash in his pocket. His father gave him 1800 pounds ($350,000 in today’s currency) to leave England. Nathaniel had violated English norms and laws when he married Elizabeth Duke without the necessary permissions of her family and the King. Nathaniel’s father satisfied the aristocratic overlords by evicting his son from England. As Elizabeth Duke had been promised to another man, Nathaniel was also charged with theft of the dowry that had been promised the ‘other man,’ the suitor she had jilted.

Nathaniel was an opportunist and used his connections in Virginia to win the favor of Governor Berkeley, before he later turned on him. Berkeley helped Nathaniel secure a job. Bacon took a small amount of the cash dad had given him and purchased two plantations in an area known as the Curles, a place in the James River replete with oxbows. One of the two plantations was Longfields, owned previously by John Davis, the brother of Samuel Davis Sr and uncle to Samuel Junior of Albemarle and John Davis.

That our family was heavily involved in Bacon’s Rebellion is evident in this historic document found in the William and Mary College Quarterly.

|

WILLIAM AND MARY COLLEGE QUARTERLY We the subscribed having drawn up a paper* in half of ye inhabitants of Isle of Wight Co. as ye grievances of said county, recant all the ‘false and scandalous’ reflections upon Gov. Sir Wm. Berkeley Kt contained in a paper presented to the Commissioners, and promise never to be guilty again of ‘ye like mutinous and rebellious practices.’ Ambrose Bennett, John Marshall, Richard Jordan,** Richard Sharpe, Antho ffulgeham, James Bagnall, Edward Miller, Richard Penny, John Davis X his mark, R. P. his mark. Acknowledged 9 April 1677. Test. John Bromfield Cl. Cu. John Marshall begs pardon in court on his bended knees for ‘scandalous words’ uttered before ye Worpfll Comrs*** (in accordance with their order) April 9, 1677. |

* * * * *

*The paper to which the rebels refer is a petition and list of grievances. The document is found in the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. II, p. 380, and is published in full online.

**The three men I have highlighted above, Richard Jordan Jr, John Davis and John Marshall are names that appear in our Smith family tree.

***The term “Worpfll Comrs” refers to ‘Worshipfull Commissioners,” the governing board for the colony. Seventeenth Century clerks were developing a short hand language, a forerunner you might say of texting and tweeting.

* * * * *

The ten men identified in the court document witnessed by John Bromfield were pleading for their livelihood, if not their very lives in the spring of 1677. The men were accused of mutiny and rebellion against the governor, William Berkeley. Berkeley has already convicted eighteen men to death and each was escorted from the courtroom out to the gallon to be immediately hung. The rebellious citizens had tried to remove Berkeley from office by petition, and when that petition failed, they resorted to warfare and burned the capital to the ground. The year of insurrection has been termed Bacon’s Rebellion.

In recanting and apologizing to the Governor these rebels made it clear that they understood they had been more than snarky in their complaints about Berkeley. They acknowledge they made “false and scandalous” statements. They promised to behave and never engage in mutiny or rebellion again. The penalty for some of the men who participated in Bacon’s Rebellion had been death by immediate execution (as opposed to say, slow death by way of dismemberment and other tactics common to the world at that time).

If Berkeley chose to spare a rebel’s life he would, at the very least, remove their properties and wealth and permit the man and his family the luxury of living in destitute poverty. If a man was willing to grovel in the gravel on bended knee, as in the case of John Marshall, the man might be able to regain some semblance of a healthy life.

The petition against Berkeley (referred to in the document as ‘a paper’) that circulated throughout Virginia has been referred to as the Declaration of Virginia. The charges against Berkeley included excessive taxes, corruption, cronyism, judicial corruption, personal enrichment and sowing the seeds of discontent. These are the kind of qualities that qualify a person as President today but were considered inappropriate back in the day. But, here’s the kick in the arse: The wealthy upper crust, the one percent of the era, were quite content to maintain Berkeley in power, if they could reap their profits. Sound familiar?

The lower and middle class may have forgiven Berkeley’s failings had he been able to trickle down the wealth of the upper class into the hands of the masses and if he had taken appropriate measures to safeguard the frontier families who were in constant hostile contact with Native forces. But the wealthy one percent came to the rescue of the corrupt Governor of Virginia. Unfortunately, they were all great grandparents in my wife, Nancy’s family. They benefitted from Berkeley’s corruption. One historian referred to Berkeley as the “most corrupt.”

There were many conflicts at play in Bacon’s Rebellion, conflicts involving political, religious and economic stress. Wealth was accumulating in the hands of the aristocratic planters and merchants and it was not trickling down into the pockets of the growing number of yeomen and the peasant class. The system has been perpetuated to this very day. We are a nation in which one percent of our population controls a majority of the wealth. Nathaniel Bacon was not a commoner, but he was able to mobilize the discontent of the common man in his effort to unseat Governor Berkeley.

The Bacons, Jordans and the Davis family were a part of the aristocracy. The rebellion Nathaniel inspired repeated a centuries old pattern in English history. Clashes among various English families occurred with the regularity of a Premier League Soccer grudge match. Knights fought amongst themselves and with the monarch for a controlling interest in the kingdom. Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia was one of several preludes to our Revolutionary War. Bacon, the brash nouveau riche knight, clashed with the Old Guard of Virginia and in that effort, he secured the support of the proletariat, the yeoman, the frontiersmen and peasant farmers. He organized an army that gave chase to Berkeley. The yeomen and peasants had been the castle dogs waiting under the King’s table, barking for a hambone. They jockeyed for a few crumbs that might fall off the table. They were the victims of Trickle-Down Economics and they were “Tired as Hell and not gonna take it anymore.”

Our ancestors in this rebellion were not yeoman. They were men who sold properties that Bacon now owned. They were his neighbors, his beer buddies and members of the House of Burgess (their Congress). They may have invented the term ‘BFF, Best Friends Forever’ or until one of us dies on the gallows.

Bacon was empowered by Edmund Scarborough, an iconic figure in my wife’s Whittington family tree and a major player and sociopath found in early colonial Virginia history. Search for his name online and you will find a wealth of information, not all of it pretty (if honestly presented). Berkeley was forced to retreat across the Chesapeake Bay to a safer neighborhood, Accomack County. With the Governor out of town, Bacon sacked and burned Jamestown.

The Whittingtons, Bowmans, Littletons and others of my wife’s great grandparents living on the Delmarva Peninsula, sheltered Governor Berkeley from Scarborough and Bacon. They worked feverishly and used their hard-earned cash to buy an army of mercenaries and indentured servants. They prepared a counterattack and watched in disbelief as Bacon had the nerve to die of dysentery. The rebellion lacked a leader and fell into disarray. The good citizens of Accomack County restored their crony, Berkeley, to power. They forced guys like John Marshall, John Davis and Richard Jordan to recant, apologize for their revolt and beg for their properties and lives. Rumors that they were stripped of their Costco membership cards are unfounded.

The First Settlements of North Carolina

The third pattern of migration (into Carolina) eventually brought me to the doorstep of William Davis and Susannah Davis Meads. My research efforts were made among many pitfalls:

• The LDS records do not record William’s parentage.

• DNA testing has not yet created a connection for this branch.

• ‘Researchers’ in online websites are copying false data and failing to notice the glaring errors in the fiction they are creating. Eager to fill in a blank they frequently copy the name William Davis (1725-1799) into their tree and show him as married to an Elizabeth Shelton (1742-1819).

• They then quote from the wrong will and ascribe numerous children to our William Davis Esq, and leave his actual children dangling in cyberspace.

I am accustomed to finding such errors and hardly bat an eye when they surface. It is predictable. However, there is one family historian in South Ditch, Mississippi who does not take lightly to finding such mistakes. Mattie McCausland Davis authored the following acidic note online:

I caution you not to take anything T. Willis publishes online regarding our family tree. He is a Willis and they have been known to fabricate family information. He never provides sources. He copies from genealogists whose glaring errors have been proven wrong over the last century and he frequently ignores his own errors. Just for example, notice that he has “daughter Sarah born 1706 of mother Elizabeth (1743-1797).” How could that be? For goodness sake! My mother cautioned me about marrying any of my Willis cousins and I should have listened. None of the three ever did me or our children any good.

To satisfy my need for scientific inquiry and historical integrity I must down a pint of Central Waters Bourbon Barrel Stout and get on with this task. A little of that Roth Grand Cru Surchoix cheese will go good with this pint.

By crafting Grand Cru® in authentic copper vats with the finest Wisconsin milk, Roth has created an original alpine-style cheese unmatched in America. Careful crafting brings out light floral notes, nutty undertones, a hint of fruitiness and a mellow finish. — This ad paid for by Friends of Roth Cheese, Monroe, WI

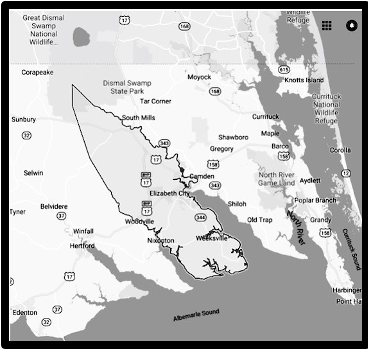

Early Carolina historians believe the first British settlers fled from the scenes of internecine warfare following the Jamestown Massacre in 1622. These early pioneers traveled on the Blackwater River, a tributary to the larger Chowan River which empties into the Albemarle Sound. These travelers understood that this waterway was the safest and most convenient way to move from the James River Basin into Carolina. Travel on the river was far easier than fighting one’s way through the dense cypress groves of the Great Dismal Swamp. A barge or small boat on open water provided for greater ease of transportation than any footpath could in this region.

Travel by sea was complicated. In 1629, King Charles I of England granted a charter to his Attorney General, Robert Heath, who promptly did nothing, for good reason. Early surveillance of the Carolina shoreline indicated there was no place that could accommodate an ocean-going vessel. Shoals of sand and low sea levels offshore wreaked havoc on ships that came too close to the coast. There was good reason for naming Cape Fear, Cape Fear. The Outer Bank was known as the Graveyard of the Atlantic, for a good reason. Heath, who had remained loyal to King Charles I, was stripped of his patent by Oliver Cromwell and the Roundheads. His descendants later redeemed themselves in America when they invented the Heath Bar.

Roads were uncommon in Virginia and Carolina, hard to create and difficult to maintain. A little known, British law adopted in 1555 placed responsibility for roads in the hands of the smallest of governmental units, the local parish. Common law on the Isle of Sark in Britain allowed the local matron, the Dame of Sark, to require adult males to contribute 6 days of labor each year toward road construction and repair. Virginia adopted these common law provisions in 1632. The entire population of Virginia has been estimated at 2,500 in 1630. The parishes were scarcely populated and the manpower just not available to grow even a minuscule system of roads. Those roads that did exist fostered traffic to and from Jamestown or other port villages. A road eventually linked the south side of Virginia to Edenton, Carolina, skirting the edge of the Great Dismal Swamp, home to many of our cousins, in laws and outlaws.

Early settlers in Carolina left little evidence of their lives. There is no paperwork documenting their presence, only the remnants of campfire stories. In the 1650s English settlers from Virginia, including runaway servants and fur trappers, began establishing homes in Albemarle, the northeast corner of the present-day state. They were joined by several early plantation owners; John Jenkins, Samuel Pricklove, James Blount and Samuel Davis, Jr who recognized the rich soil available for cash crops. These were the first recorded British/Carolina settlers in history.

Small settlements composed of only several families each, began appearing as early as 1650 along the eastern shore of the Chowan River. In 1653 a patent of 10,000 acres along the Roanoke River and west side of the Chowan River was given to Roger Green who was identified as “clarke.” The term ‘clarke’ was used to identify clerks, or clergy of the Anglican church. While he may have been a member of the clergy, Roger did not appear as a man interested in establishing an individual church or even a circuit of churches for which he could take charge. There were no parishioners to be found on the banks of the Chowan and no income to be earned proselytizing the Natives. In his visit to Virginia and Albemarle in particular, Green appeared as a point man for the Anglican Church, conducting reconnaissance for future evangelical work and troubleshooting the issues confronting the church in Virginia. There is no evidence of any church activity, other than Quaker, in 17th Century Carolina and the Quakers were humble in sharing their faith with the Native population and less likely to insist on a conversion or even a donation to the construction of their first meeting house on Little River. The Quaker lineage in the Davis branch of our family tree is extensive. The Founders of Carolina include family names found in our tree: Roger Green, George Durant, Roger Williams, Samuel Davis and a cast of others including the heads of the Quaker Nation, Governors of Carolina and a Pirate or two.

Roger Green from Norfolk, England matriculated at St. Catharine’s College, Cambridge in 1631 and graduated with a B.A. in 1635. He received the M.A. degree in 1638 and was ordained in Norwich on March 9, 1639. In 1653, the Virginia Assembly acted favorably upon Green’s request for a grant of 1000 acres of land for himself and 10,000 acres for one hundred inhabitants of Nansemond County. The original record reads as follows (copied verbatim, including spelling):

| “Act of the Virginia General Assembly concerning a land patent to Roger Green and the inhabitants of Nansemond River in Virginia

Virginia. General Assembly. UPON the petition of Roger Green, clarke, on the behalfe of himselfe, and inhabitants of Nansemund river, It is ordered by this present Grand Assembly than tenn thousand acres of land be granted unto one hundred such persons who shall first seate on Moratuck or Roanoke river and the land lying upon the south side of Choan river and the branches thereof, Provided that such seaters settle advantageously for security, and be sufficiently furnished with amunition and strength, and it is further ordered by the authority aforesaid, That there be granted to the said Roger Green, the rights of one thousand acres of land and choice to take the same where it shall seem most convenient to him, next to those persons who have had a former grant in reward of his charge, hazard and trouble of first discoverie, and encouragement of others for seating those southern parts of Virginia.” |

+ + +

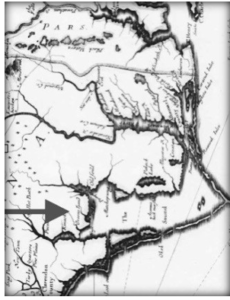

The arrow on the map to the left points at a term posted vertically as “Greens Land.” I have flipped and enlarged it (on the right) for your viewing pleasure.

James River, Jamestown and Fort Henry are at the top of the map on the left. The tip of the Delmarva Peninsula is also found to the extreme, upper right-hand corner of the image on the left. Roger Green was to select a secure site for settlement and be prepared to defend it. ‘Security,’ ‘amunition,’ and ‘strength’ were important conditions that had to be met.

He was to choose a location “next to those persons who have had a former grant.” Existing archives do not reveal a recording of ‘former grants’ that led to any settlement of consequence. We do know there were a few small and remote settlements, but they were all located closer to the present-day Virginia state line and north of the Albemarle Sound. The positioning of the term ‘Greens Land’ on the map near Pamlico Sound and present-day Pamlico County implies that there were existing grants near New Bern, which blossomed into a major center of commerce and government in the 18th Century. The Assembly acknowledged that Green undertook personal expense and put himself at risk when he explored this previously uncharted territory of Virginia. They rewarded him for his time and effort with the additional 1000 acres: “in reward of his charge [expense], hazard and trouble of first discoverie, and encouragement of others for seating those southern parts of Virginia.”

There is no evidence that Green settled on his 1000 acres and historians have found little evidence that settlers made immediate use of Green’s 10,000 acres grant. The land was eventually occupied over the latter half of the 17th Century and in the 18th Century.

There is something in the Carolina soil that sucks the evidence of early settlements into quick mud, sink hole or subterranean system. Perhaps Middle Earth is located beneath the Carolina coastal plain. Think about it: The Lost Colony of Roanoke Island disappeared leaving only the word ‘Croatoan;’ on a tree. Refugees from the Jamestown Massacre fled into Carolina and left little evidence: no Coors aluminum cans, no plastic six pack thingies, no trash heaps of Ziploc bags and plastic bottles, nothing. Trappers and servants ran away into the swamp land and left no sign of their existence: no toilet paper rolls, no Marie Callender packaging, no McDonald fry bags, no Goodyear tire dumps. These early immigrants were swallowed up by the Cypress forests in whose roots they became entangled. Or worse yet, they were chomped up into little bits by hungry alligators who were looking for a quick snack. I don’t know. But I do know that the area denoted on that map as Greens Land was eventually populated by the Davis, Wilkinson, Blount, Mead and others of our connected families.

Roger Green was an early version of a community development resource person. If he were alive today, he would be working in Detroit or Pittsburgh on a downtown revitalization project. You would find him in small town America talking to city councils and Chamber organizations about their Main Street program. His pamphlets, his letters to Parliament and speeches reflect his strong interest in seeing a system of towns established in Virginia in contrast to the scattered haphazard farms and plantations that littered the landscape of the colony.

Green was in Virginia in 1656 and witnessed a discussion in the House of Burgess. He reports “hearing some members of the new Assembly express regret at the repeal of an act to establish central market places in each county.” Central markets, town squares, village greens were all essential elements in an English village. They were missing from the Virginia countryside. Five years later Green was in London and delivered a twenty page, carefully crafted rant to the Bishop of London. His statements, oral and written, were intended to reflect on “the unhappy State of the Church in Virginia” and to enter a plea for the establishment of villages as a solution that would put an end to several evils that he saw as problematic in the colony.

His report was printed in 1662 in a pamphlet entitled Virginia’s Cure: or An Advisive Narrative Concerning Virginia (found online). In the first half century of colonial development, men like Green were noticing a distinctly new world phenomenon in the southern colonies. Unlike European farmers who left their villages in the morning to tend to rural crops and livestock, the southern plantation owners lived a far more secluded life, isolated on individual plantations throughout the week 24/7/365. Villages were rare sites. As colonial pioneers eradicated the Native population on the coastal plain, the need for palisade fortresses that provided community safety, a la the English castle, dwindled. Such designs were still necessary in the intermountain regions of the Appalachian frontier but were no guarantee of survival.

Coastal plantations in Virginia and early Carolina were connected more by waterways than roads and the rare villages that did exist early on, tended to be seaport facilities through which the necessities of daily life were transported. The sole seaport for seagoing vessels in Carolina was found in Charles Town (Charleston, SC). Port facilities in the remainder of Carolina served small inter-coastal merchant craft capable of taking produce to larger Virginia deep harbor ports from which the goods could be shipped to England on larger ships. This would become a problem when Carolina became two colonies (North and South) separated from Virginia.

Trade between colonies was not allowed. The British Navigation Acts required that resources must leave Virginia for England only. Goods could then be dispersed from English ports in England to Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, etc. North Carolina could no longer legally send produce to Virginia by way of the intercostal waterway. British investors and middlemen took their profits as they returned goods to the colonies.

It was into this environment that Virginians propelled themselves as they pressed south from Nansemond. It was Green’s conclusion that plantation owners needed to build their homes in community settings and leave overseers in charge of the daily work to be done on the plantation. This would encourage the growth of wealthy families living communally, supporting local churches, schools, the arts and humanities. The plantation labor force could then congregate in villages on Sundays and support the church, local artisans and retail. Green was conspiring with others in an early version of the Shop Local phenomenon that periodically sweeps the nation today. He was also looking for ways to recreate the class system that prevailed in Britain with the aristocracy firmly entrenched and in control of community life. Green viewed the church as the Gorilla Glue that held everything in place and in check. The word ‘theocracy’ comes to mind.

Roger Williams (1625-1677) acquired a large patent of land in 1663, had it surveyed and began parceling it out in smaller deeds. Roger is an 8th great grandfather found in the Kincheloe branch of our family. He was a nephew of the preacher Roger Williams whose followers established the colony of Rhode Island. Our Roger’s daughter Ruth married John Canterbury. Ruth’s daughter Elizabeth married John Kincheloe (1694-1746) and their daughter Elizabeth married Isaac Davis. And it just spins out of control after that in the hills of Kentucky. It doesn’t end well as there are at least two encounters with Native populations that end in massacres: One of which occurred at Fort Kincheloe KY and the other in the prairie farmland between DeKalb and Ottawa, Illinois, 160 years after Roger Williams secured his patent in 1663. For light, entertaining reading that will pair well with your morning coffee read the appended Indian Creek Massacre.

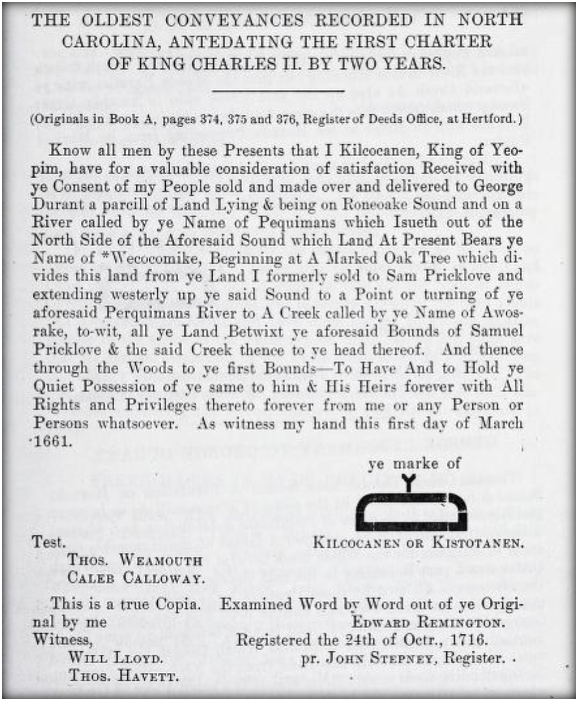

George Durant, one of the first English settlers to maintain a home in Albemarle, purchased two separate tracts of land (see left) in 1662 from two Yeopim tribal leaders: Kilcocanen and Cuscutenow. The land in Virginia was viewed as the Natives right to sell. In 1665 the King of England revised the rules for land ownership. George Durant’s property became Carolina dirt and Durant’s deed with Kilcocanen was declared null and void. Kaput.

George Durant, one of the first English settlers to maintain a home in Albemarle, purchased two separate tracts of land (see left) in 1662 from two Yeopim tribal leaders: Kilcocanen and Cuscutenow. The land in Virginia was viewed as the Natives right to sell. In 1665 the King of England revised the rules for land ownership. George Durant’s property became Carolina dirt and Durant’s deed with Kilcocanen was declared null and void. Kaput.

Durant had great difficulty holding on to several parcels of his lands. It wasn’t just the Lord Proprietors who were trying to swindle him. George Catchmaid, a wealthy British speculator and con man, moved to Albemarle on the advice of Durant. At the invitation of Durant, he settled on a tract next to Durant. Durant helped him fell trees and clear land. When the king and proprietors imposed the 1665 land reforms Durant was told he would have to journey to Jamestown to secure new patents on his old lands. Catchmaid offered to save Durant the trip and went on his behalf. Catchmaid promised to secure the patent for Durant while he was getting a patent for his own land. While in Jamestown, Catchmaid lied to the Deeds Office and had Durant’s land included in the patent he was seeking for his own property. He thus held legal title to what had been Durant’s land. This land never returned to Durant’s ownership. Decades later, his son would finally secure possession via the court system, long after Catchmaid and George were dead.

Pasqoutank and Perquimans Counties, NC

Geography 101

You may wonder why I am focusing so much attention on this Davis branch. My father was only five years old in 1927 when Jane Stilley passed away. His grandmother had come to live with his family when she was single, and he had no real memory of her, only the stories and the affection his parents had for Jane Stilley. My father had an Uncle Davis (Leb’s brother) with whom Leb lived in Idaho and the Dakotas. His name would surface in my father’s stories, stories that he had heard told by Grampa Leb. When Dad passed away he knew nothing of the history that flowed through the Davis DNA of Jane Stilley. I am compelled to unlock the doors, open the windows and view the Davis past. The task required an understanding of colonial and county history, deeds, wills and geography.

And, it also required a healthy diet of Nueske’s bacon and hams.

Nueske’s is a third-generation family company offering an unforgettable family breakfast chock full of the world’s finest quality apple smoked bacons, since 1933. –Paid for the Friends of Nueske’s Applewood Smoked Meats.

Virginia originally included North and South Carolina as one large province called Carolina. Albemarle County was one of three counties that constituted the Province of Carolina in the Colony of Virginia. The other two counties were Craven and Clarendon. Albemarle was initially divided into three precincts: Carteret, Berkeley and Shaftesbury. Carteret included present day Pasquotank, Currituck and Camden counties. Berkeley Precinct included Perquimans. The eventual counties of Pasquotank, Chowan and Perquimans Counties were the homeland of our earliest ancestors in Carolina, the first stop on the highway to Hyde County NC.

The archives reveal that Stilleys, de la Fontaines, Jordans, Carters (names found first in Virginia in 1640) and others of our tree joined the Davis family in Hyde County in the decades of 1740 and 1750. I will point them out to you as we go along the path through the swampland and cypress groves of the Carolina countryside.

Editor’s Note: “Your plug for Nueske products inspired some major backlash online among your second cousins in Virginia. You may want to respond to this one in particular:”

Hey Dog Breath!

You’re a traitor to your ancestors in Virginia! Scumbag! You say you are a Smith by birth. I wouldn’t know that by your praise of Midwest pork. Do you even have pigs in the Midwest? I doubt it. You are a Smith and you should stand tall for our Smithfield Hams here in the home country of your Peter Smith. Dig a little deeper dufus. You might find your brain.

God’s Blessings Always, Cousin Leonard Davis Blount III

Authors’ Response: “Thank you Leonard for your kind words and blessings. Now back to a continuing geography lesson.”

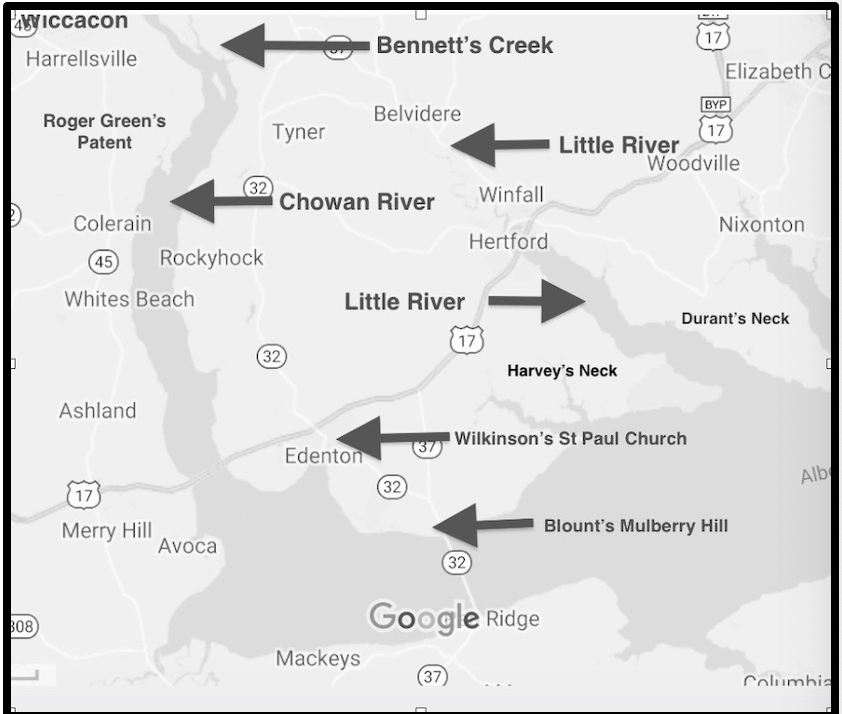

Pasquotank County is shaded in gray. It looks like an arrowhead on this map, pointing north and west. Camden and Currituck Counties are to the right of Pasquotank and Perquimans County to the left. The terrain is characteristic of North Carolina’s Coastal Plain: flat and near sea level. The southern neck of the county extends between Little River (left) and the Pasquotank Estuaries (right). These rivers drain the Great Dismal Swamp. The state of Virginia lies (shaded slightly gray) to the north. The islands of the Outer Bank are to the far right. The ancestors of William Davis developed plantations among the estuaries of Pasquotank and Perquimans Counties with the sandy shoals of the Outer Banks just to the east.

Pasquotank County is shaded in gray. It looks like an arrowhead on this map, pointing north and west. Camden and Currituck Counties are to the right of Pasquotank and Perquimans County to the left. The terrain is characteristic of North Carolina’s Coastal Plain: flat and near sea level. The southern neck of the county extends between Little River (left) and the Pasquotank Estuaries (right). These rivers drain the Great Dismal Swamp. The state of Virginia lies (shaded slightly gray) to the north. The islands of the Outer Bank are to the far right. The ancestors of William Davis developed plantations among the estuaries of Pasquotank and Perquimans Counties with the sandy shoals of the Outer Banks just to the east.

Perquimans County highlighted in a lighter shade of gray, is found on the Albemarle Sound, south of the Great Dismal Swamp. The Perquimans River divides the county in half from northwest to southeast. It is a coastal waterway that ebbs quite slowly on the way to the Albemarle Sound, draining the swamps of the tabletop flat lands to the north. The murky waters slither through cypress swamps between Durant’s Neck to the right and Harvey Neck to the left. The river transitions into a tidal estuary just south of the town of Winfall on its’ was to the Sound.

Perquimans County highlighted in a lighter shade of gray, is found on the Albemarle Sound, south of the Great Dismal Swamp. The Perquimans River divides the county in half from northwest to southeast. It is a coastal waterway that ebbs quite slowly on the way to the Albemarle Sound, draining the swamps of the tabletop flat lands to the north. The murky waters slither through cypress swamps between Durant’s Neck to the right and Harvey Neck to the left. The river transitions into a tidal estuary just south of the town of Winfall on its’ was to the Sound.

Durant and Harvey are cousins in our family tree. The Davis families moved south into Perquimans, Pasqoutank, Rowan and Beaufort Counties. Davis Plantations were commonplace and changed hands by sale of deed and the power of attorney in wills. The lives of the black humans who served as slaves to the white owner, also changed hands in wills left by the deceased. Land, chairs, mirrors, a piece of silver plating and a ‘negra girl named Liza’ would be left to the son or daughter of a plantation owner with a simple, “To her and her heirs forever.”

In July of 1670 the people of North Carolina, under the direction of the British monarch organized a rudimentary system of government. State commissioners were selected to work with Governor Peter Carteret. In the absence of a state capitol building or even a county courthouse, the officials met in the various homes of commissioners and officials. The official record (minutes) of the first such meeting began as follows:

“At a called Court, held the 15th July 1670, at ye house of Samuel Davis, for ye county of Albemarle, in ye Province of Carolina. Present, the Honorable Peter Carteret, Governor and Commander in Chief, Lt. Col. John Jenkins, John Hardy, Major Richard Foster, Capt. Thomas Cullen, Council.”

The Samuel Davis mentioned as the host of the Governor’s council was our Samuel Junior (1631-1688) recognized in documents as a planter and son of Samuel Davis, Sr of Isle of Wight Co VA.

Samuel Davis Jr made his will in Albemarle, January 11, 1688, and the abstract for that will named only a wife Elizabeth and ‘all my children.’ The abstract of his will does not identify Samuel’s children by name. The seal on his will bore the device of three arrows and a tomahawk. Historian and author, John Bennett Boddie, observed in his work, Seventeenth Century Isle of Wight County, Virginia, that

“a late 17th century will, made in Ablemarle by Samuel Davis, used three arrows and a tomahawk as his seal. Compare with similar symbols for Algonquin werowances shown in Theodore De Bry’s engraving The Marks of sundry of the Chief men of Virginia Hulton, America 1585, figure 26, page 12.”

Theodore DeBry (1528-1598) was a world-famous engraver and publisher. His work depicted early European expeditions to the Americas. While he had never set eyes on the New World, he borrowed heavily from an artist who had spent some considerable time in Carolina, John White. White was the commander responsible for the settlers in the Lost Colony of Roanoke. He was the grandfather of Virginia Dare, the first of the British to be born in the New World (in Roanoke). White was forced by conditions on the island to abandon his family and friends and return home to England seeking aid for the forgotten and soon lost colony. He was to never see his family again. While in Carolina he made extensive notes on Native culture and produced numerous watercolor paintings depicting the Native dress, rituals and community life. His work is legendary on so many levels: artistic merit, ethnography, cultural insight and historical value. It was as if he had a cool cell phone that could take photographs of the Natives while they ate, danced, prepared for war, celebrated the harvest and played Mario Kart, Dungeons and Dragons and the first incarnation of Jarts, using real spears.

Every decade or two, the British would explore Roanoke Island and trek inland a bit in search of evidence that would either explain the disappearance of the Roanoke colonists, or locate the descendants of the original lost colony. There was a long-standing hypothesis that the English had been absorbed into the Native population. Samuel’s seal, the three arrows and tomahawk, reflected an appreciation for native culture. We do not know why Samuel Davis devised his seal in such a manner, and Boddie only calls attention to the uncanny similarities of Sam’s design with those found among the art of the Native werowances (chiefs). I hate when that happens. Wouldn’t it be awesome if Boddie announced that he had found traces of the Lost Colony residents among our ancestor’s possessions and that we are descended from the survivors of the ordeal? An interesting side story could emerge. John White, the artist and Roanoke magistrate does fit into the family tree as part of the White clan found in both Davis and Slaymaker twigs of our expansive tree. Our ancestors survived many ‘real time’ ordeals to get us to where we are today. I am ashamed to admit that I complain if the internet is slow.

In Summary

If this were Let’s Make a Deal, there would be three doors in front of us and our host, Monty Hall or present-day Wayne Brady, would offer us a choice. Behind Door Number One we would find Captain Thomas Davis (1613-1683) of Nansemond and his descendants. Behind Door Number Two we would find Samuel Davis Junior (1631-1687). Door Number Three would conceal John Davis (1635-1713). Each of these three families has the potential to lead us to William Davis, Esquire, a man from whom we descend.

Door Number One: Several of the children of Major Thomas Davis (b 1613) migrated in a northerly direction from their initial base on father’s estates in the James River Estuary. They were found along the Rhappahannock River in northern Virginia, and living in Somerset County MD. Their pathways lead us to the Kincehoe branch of our tree.

• Son James (1642-1648) of Major Thomas did remain in Nansemond County VA, but the sons of James did not venture into Carolina and tended to migrate north or to Europe.

• Son William (1643-1680) of Major Thomas, did migrate into Pasquotank County NC.

• Son Thomas (1645-1705) of Major Thomas, stayed put in Nansemond VA but his grandson John spent his adult life in Hyde County NC, dying there in 1795, in the company of our William Davis, Esq.

Door Number Two: The 1688 abstract for the will of Samuel Davis Junior provided very little insight into his offspring. The case against Samuel Davis III brought by Alice Bilitt, sister of Samuel III, did reveal the names of the children of Samuel Davis II. The case, as reported in council meeting minutes dated 1700 revealed not only the children of Samuel Davis Jr (d 1687) but also a painstakingly slow judicial process. The following passages expose a court that was reluctant to assist a woman while catering instead to the ‘Good Old Boys.’

“At a Council held at the house of the Hon. Major Samuel Swann. Present: the Hon. President the Hon. Major Samuel Swann, the Hon. Col. Thomas Pollock; The Hon. Francis Tomes; the Hon. W. Glover.

Petition referred to this Honorable Board by Alice Bilitt: that her brother Samuel Davis III hath taken part of her plantation by survey which land her father (Samuel Jr) bounded by marked trees and Seated her upon the Said land She having had quiet possession of it from the date of a Receipt given by Robert Holden in the year 1679 until the time that her brother made his survey and praying to be restored to the same again.

Ordered that the Said Samuel Davis III be summoned by the Provost Marshall to appear at the next council to answer the said petition.”

Samuel III had a sister Alice, who argued in court that her brother had wrongfully surveyed land bequeathed to her by their father, Samuel Jr (d 1688). The land previously held by Robert Holden was sold to Samuel Jr in 1679. Samuel III messed with the survey lines in 1700 and Alice lost land as a result. She wanted that land returned to her possession. The council ordered Samuel III to appear at their next council meeting and respond to the complaint filed by his sister Alice.

Three years later, in 1700, Alice returned to council on August 23, 1703, and the recored reveals:

“The humble petition of Alice Bilitt humbly asks…. if it pleases the governor with his assistance to answer your petitioner (Alice): that I may have my just right in my land restored to me again and your petitioner (Alice) shall forever as in duty pray. This: 23 day of August 1703 Alice Billet”

It appears from the record that for three years, Alice did not receive any response and the disputed property remained in her brother’s hands. As we shall see in the next entry (dated 1719, nearly 20 years after the initial petition) Alice turned her attention to a gentleman by the name of Captain Benjamin West.

“At a Council held at the House of William Duckinfield, Esq. April 3rd, 1719. Present the Hon. Charles Eden Esq. Governor Captain General and Admiral. The Petition of Soloman Davis, Alice Billet, Sarah Ward and Tamer Creech being the Children of Samuel Davis Deceased was read, and Alice Billet being called and She informing the Board that Capt. Benjamin West has dispossessed her of part of the Estate left her by her said Father without any manner of Pretense that She knows of.”

“Ordered that the said Benjamin West attend this Board at its next Sitting which will be at Matchacomack Creek the Thursday following the opening of the next General Court.”

The decades long dispute identifies Davis family members who were alive and well in 1719, including Tamar Davis Creech. Because the name ‘Tamar’ (Tamar Keel) occurred in the family records of William Davis Esq in the mid-18th Century, I have made note of Tamar Davis Creech. I will stalk her. I will hunt her down. I will order an autopsy if I must, exhume her bones from her grave and drain her of DNA. It isn’t that important. Darwin’s Syndrome is kicking in again.

Samuel Davis Jr, the first of the citizens of Albemarle (North Carolina) died April 26, 1688. His will as revealed in Probate identified his “wife Elizabeth and my children.” The court battle that ensued, over the course of decades, between Samuel III and Alice Bilitt brought out the names of several of Samuel Jrs’ children. I will list there him only to help any future research efforts:

1. William (1662-1719)

2. Tamar Elizabeth (1662-1719),

3. Soloman (1663-1737),

4. Samuel III (1663-1715),

5. John (1664-1745),

6. Alice (1666-1725),

7. James (1669-1748),

8. Sarah (1670- ?).

I believe many of these dates given are estimates created from LDS files. To my knowledge they are accurate, give or take several years.

As information from the 17th Century (1600s) unfolds I feel the Gordian Knot beginning to unravel a bit more. I think I am making headway in pruning our tree. Before looking behind Door Number Three, it is time to stop and enjoy the latest brew from our friends at Central Waters Brewhouse. I am torn between drinking the immensely popular Octoberfest with its’ enticing, bready maltiness, characteristic of traditional Marzen-style lager; or the Slainte Scottish Ale with its’ rich malt reminiscent of dark fruits, and deep flavor of cherry wood smoked malt. This ad paid for by Friends of Central Waters Brewing Co, Amherst WI.

Door Number Three: John Davis died 1714 in Upper Parish, Isle of Wight County, Virginia. The Will of John Davis, dated December 31, 1712, provided rich detail of his family, including siblings, children, in laws and friends. A will like this is a blessing when stalking ancestors.

“wife Mary, son Samuel, son Thomas land in Surry, which was bought of Edward Grantham; son John; daughter Sarah; daughter Elizabeth; daughter Prudence; son William, the land on which Thomas Robertson lived; daughter Mary the wife of William Murray; granddaughter Elizabeth Murray, the daughter of said William; brother William Green, friends Nathaniel Ridley and James Day to make the division of my estate. Wife executrix. Witnesses: Nathaniel Ridley, Richard Webb, Thomas Webb, Mary Maccodin. Recorded June 28, 1714.”

The wife of John Davis, Mary Green Davis, died in 1720. Her will, dated Sept 20, 1720, confirmed family ties and added insight into her branch of the Davis tree. It named:

“Legatees: daughter Prudence; grandson William Davis; son Samuel; and all of my children. Daughter Prudence Davis to be Executrix and I request Captain James Day and my brother William Green to assist her. Witnesses: William Green, Sarah Murray, Thomas Davis. Recorded Jan 23, 1721.”

Not named in the will of Mary Davis nee Green (as recorded in 1721) but appearing in her husband’s will was daughter Mary (wife of William Murray). Notice that Sarah Davis married William Murray (her brother-in-law), both had lost their original spouse.

Also, not mentioned in Mary Green’s will were her sons, John and William Davis. I assume Mary’s son William* predeceased her, as she refers to her ‘grandson William Davis’** instead. I will highlight the grandson’s name (**) in my notes and track his life via deeds and wills when the opportunity arises. All of this information may help estimate birth and death dates for men who carry the Davis family name forward to William Davis, Esquire (d 1802). I am still testing the hypothesis that he descends in this burgeoning tree.