Happy St. Patrick’s Day 2021

Ancestry.com just confirmed what I have always known. My DNA results tell me that I am sixty percent Celtic. Breaking that down into nationalities: I am thirty six percent Irish, fifteen percent Scot and roughly ten percent Welsh. The remainder of the DNA (40%) reflects English and Germanic roots and the effect of the Stille families Scandinavian heritage.

I didn’t really need the DNA results to confirm the ethnic composition of my life’s blood. I will be using the DNA markers to further trace our Smith family roots, our bloodline so to speak. When I last researched the topic I left Peter Smith of Westmoreland on his deathbed in 1741, on grounds that would later become a part of the American Civil War campaigns at Bull Run. The DNA referencing Welsh blood, may hold a clue as to where I could find Peter Smith’s father. We shall see. The more dominant English markers suggest a tie to Berkshire and the Smiths residing at Swallowfield.

* * *

Today, being St. Patrick’s Day, pulls my attention into that part of our family tree that is rooted in the ‘auld sod,’ Ireland. I can see my father now, drawing a bit of smoke from a Walter Raleigh blend of tobacco burning in his pipe as he sits composed in his white Arran wool sweater. There would be a bit of Baileys in the proper glass at his side and he would effect an Irish lilt as he spun a yarn from his memory of tales told by his mother, the very Irish, Mary Hughes Smith.

The first of our Irish ancestors arrived on this continent in the form of my great great grandfather, Edward Hughes (1810-1893). He was not alone. Equally important was my great great grandmother, Ann Dooley (1822-1884). Let me begin with an apology. Edward and Ann are also the 2x great grandparents of my sisters and all of my first cousins on the Smith side of the family tree, anyone descended from Leb and Mary Hughes Smith. From this point forward I will be using the term ‘our’ to include all such descendants.

I would be remiss if I didn’t include several other equally important Irish families that are a part of our Gaelic ancestry: the Banks, the Byrnes (Burns), Mulvaneys and Dunnes. The Felloons and Fitzgerald cousins and the Clavins as well. And there are Mahans in the picture, every step of the way, but why? I can’t say. But they are there also.

And the Mahans are important. While I can’t find evidence that we descend from a Mahan, their tie to our ancestors represents a close bond found among old friends who grew together in Europe, in this case Ireland, and emigrated together across the ocean, through a portal and across North America. Leaving a home in Ireland, France, a German principality, or Welsh village was not an easy thing to do. Camaraderie was often as important as food for sustenance. Whether it be my mother’s Germanic heritage in DeKalb County, Illinois, or my wife Nancy’s ancestors in Pennsylvania and Virginia, I find evidence of immigrants bound together in mutual support groups. They established enclaves sharing culture, religion, norms and mores that brought comfort to a hard life.

Edward Hughes per my DNA appears to have been living in Leinster, one of four provinces of Ireland (Leinster, Munster, Connacht and Ulster). In the Irish language these geo-political divisions are referred to as a cúige, meaning ‘fifth part.’ Up until the 12th Century, Meath was that ‘fifth part.’ It was later absorbed by Leinster and Greater Dublin. And of course, Ulster became a separate and largely protestant unit governed by England. One cannot safely define Northern Ireland as a province, region, country or something else without eliciting anger from one direction or another.

Our great grandfather, John Benedict Hughes, was born in Harvard, Illinois, so it is safe for any one of us to say we have a Harvard background, if that is important to you. I doubt that it is. To be more precise, it appears JB was born on the outskirts of Harvard, in McHenry County. I submit the following evidence that after a brief excursion through New York, Edward Hughes and his band of Irish immigrants landed in the rich farmlands of northern Illinois.

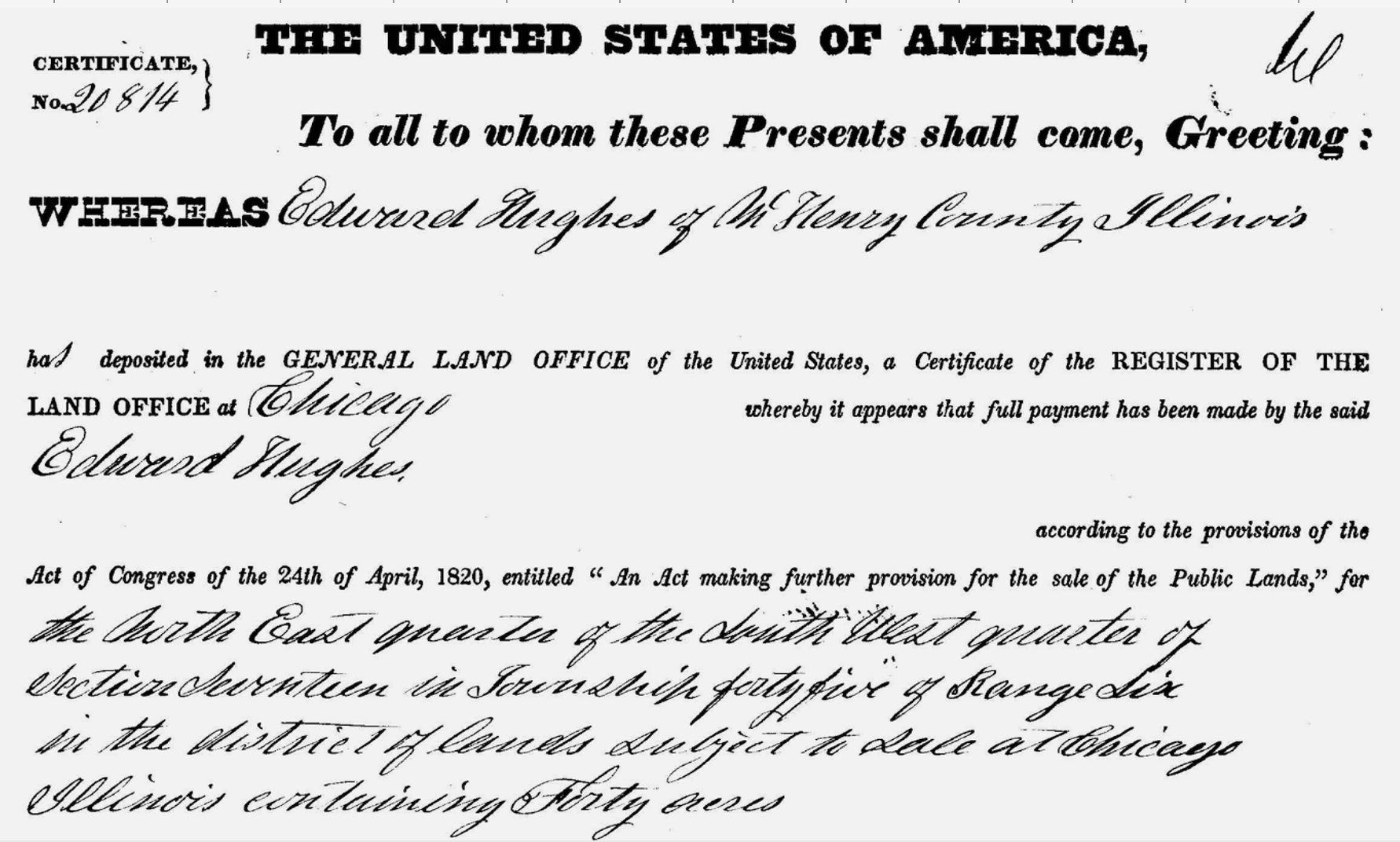

Ed secured 40 acres of McHenry County land shortly after his arrival in 1848. The exact location of the land is defined in the paragraph shown on this copy of the original deed. I am only presenting the top half of that deed. The remaining half carries the usual flourishes and signatures of the local, state and federal officials and politicians who wanted to brand their name into the mind of any immigrant who might appreciate the land and vote their gratitude in any election. President Polk was a signatory.

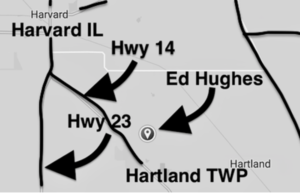

The 1848 deed reads: “The North East quarter of the South West quarter of Section Seventeen in Township forty-five of Range Six in the district of lands subject to sale at Chicago Illinois containing forty acres.” Using this information (45N 6E 17) and consulting the McHenry County online plat map; the Edward Hughes homestead appears in Hartland township, as marked on the map, north of Paulson Rd and west of Lembcke Road, just off Highway 14, SE of Harvard IL. The property is heavily forested. The GPS coordinates are as follows: 42°22’35.70”N and 88°33’45.88”W. Plug those into Google Earth and you can see the small forest preserve that was Edward’s homestead. Seriously. I’ve done the homework for you!

The 1848 deed reads: “The North East quarter of the South West quarter of Section Seventeen in Township forty-five of Range Six in the district of lands subject to sale at Chicago Illinois containing forty acres.” Using this information (45N 6E 17) and consulting the McHenry County online plat map; the Edward Hughes homestead appears in Hartland township, as marked on the map, north of Paulson Rd and west of Lembcke Road, just off Highway 14, SE of Harvard IL. The property is heavily forested. The GPS coordinates are as follows: 42°22’35.70”N and 88°33’45.88”W. Plug those into Google Earth and you can see the small forest preserve that was Edward’s homestead. Seriously. I’ve done the homework for you!

A side note: More than a century later, another remarkable Hughes moved into the township buying up an old Hughes farm. Filmmaker John Hughes sought an escape from Hollywood and resided 6 miles directly north of the Edward Hughes homestead. John Hughes wrote and occasionally directed a ton of popular movies including Breakfast Club, Home Alone, Ferris Bueller, Sixteen Candles, Pretty in Pink, Mr. Mom and a series of movies done in collaboration with John Candy. The list would be incomplete if I did not include Christmas Vacation. His early movies became cult classics. Home Alone grossed $285,761,243 in just four years and marked a turning point in the writer’s career. His later movies followed a cookie cutter pattern that dodged critical acclaim and pursued profits alone.

Born in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, the screenwriter/director moved with his parents to Glenbrook, in northeastern Illinois where Hughes graduated from Glenbrook North High School. His early films often depicted teen life in the Chicago suburbs. When Hughes bought property in the Hartland Township there was a report that one of Ed Hughes’ descendants had returned home to his roots. I have found no evidence that one of Hollywood’s great director/screenwriters, John Hughes (1950-2009), is sharing a branch of the Edward Hughes tree with the rest of us. But there are rumors to the effect online and in the narthex of a rural catholic church in McHenry County.

Our Edward Hughes wrote his own piece of dramatic history when illness threatened the very life of his children. My father’s recollection of events was that death was at the doorstep of the Hartland Township farm house in mid-winter. Ed needed to locate a prescription drug for his family. As the story was told, Ed journeyed through winter weather conditions, on foot to Chicago, to get the drug. He made the round trip in forty hours.

The story survived as one of several great family legends that my dad liked to recall on occasion. Of course, the story was embellished from beginning to end and each time it was told the winter weather evolved into Arctic blizzard conditions and a journey that began as a jaunt to the local drug store turned into an epic 100-mile round trip to the heart of the Chicago metropolis. Somewhere amid all the verbiage, as with my efforts, lies a kernel of truth and the point is made: Ed Hughes, vaunted Dublin pugilist, loved his kids and risked his life that they might live longer.

But what do we know of Ed’s life, and that of his wife Ann Dooley?Ed Hughes Sr was born circa 1810 and died in 1898 in Harvard IL. At the time of his death Ed Hughes (b 1810) was 88 years of age. My grandmother Mary was 15. She lived more than 500 miles apart from her grandfather. The first time she may have set eyes on the man he was more than likely lying in a closed coffin to be buried in the Springfield, South Dakota cemetery. His passing was noted in an obituary found in the Springfield Times, Thursday, November 24, 1898:

“Mr. Edward Hughes, father of the Hughes boys who reside in Albion precinct, died at his home in Harvard, McHenry County, Illinois last Friday. The remains were shipped to this place for burial and arrived Tuesday evening. The four sons, Edward, John, Michael and Thomas have the sympathy of our entire community. The funeral services were held from the Catholic church yesterday and the remains were interred in the Springfield cemetery.”

The Tyndall newspaper added a social note to an otherwise similar obit:

“Mrs. H. Saville of Keystone, S. D., sister of the Hughes boys, arrived the forepart of last week to attend the funeral of her father, Edward Hughes. She will make a several days visit with old friends in the county before returning to her home.”

There is more to know about the life of Edward Hughes than his death. And there were more of his children than listed in the South Dakota newspapers. The South Dakota newspapers only carried the names of those of Edward’s children who lived in South Dakota. They knew little of the man, only that the Hughes kids were coming to Springfield SD to plunk a coffin into the earth of the St Aidan’s cemetery.

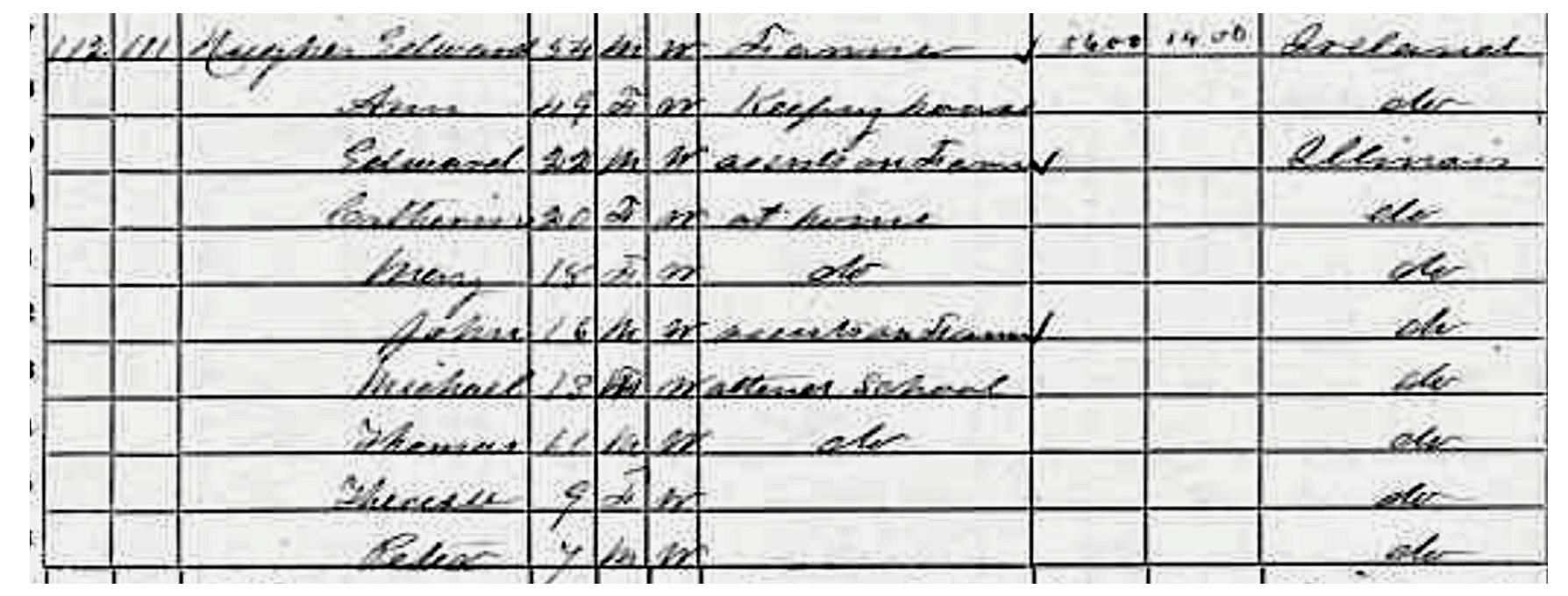

The Census record in McHenry County, IL in 1870 revealed the full extent of Edward’s effort to populate the nation with a second generation of Irish children. The print on the page was faded when I copied it.

The names of his children include Catherine (Katie), she of the silver tube and tragic death. She is shown as 20 years of age in 1870. Great grandfather John (JB) is listed as 16 and as a farmer. The other children itemized on the census include oldest brother Edward (age 22), Mary (15), Michael (13), Thomas (11), Theresa (9) and Peter (7).

The name I consider most valuable on this faded page is ‘Ann,’ the wife of Edward Sr. She is identified as 49 years of age in 1870 and occupied as “keeping house,” which had to be a full-time job with 11 people in one farm house. This would put her year of birth at circa 1821. The census also reveals that Edward Sr was a farmer who was born in Ireland as was Ann. Their children are all identified as being born in Illinois.

The 1865 Census is formatted differently than the 1870 census. The ’65 Census enumerated but did not name children. It also revealed economic data related to ‘Manufacture and Agricultural.’ Edward’s livestock, grain crops and estate were valued greater than any of the other 37 farm families listed on the page in which his name appears. The total value given to his properties was meager by today’s standard: $1507 ($23,300 in 2018 currency). He was far more heavily invested than his neighbors in livestock.

The 1850 Census was defaced and barely intelligible. Edward Hughes was living in Hartland Township of McHenry County IL. In each of the census documents reviewed Edward Hughes and John Mahan are identified as neighbors. John was married to Mary Dooley, Ann’s sister.

The tombstone of Ed Hughes states that he was born in County Dublin in 1810. Ed was a devout Catholic and attended mass on Sundays then practiced fist fighting in a lot behind the church. On weekends Dubliners would fill stadium seats where staged fights on the hurling fields were common. Stadium seats would fill early and pints of beer would flow freely throughout the afternoon. Ed Hughes was one of several fighters whose reputation drew more than a few fans.

The circumstances in Ireland in the 1830s were looking promising for Irish Catholics. Under the leadership of Daniel O’Connell the Irish Catholic Association made great strides in gaining emancipation from harsh British rule. The Penal Acts had largely disappeared earlier in the century and O’Connell focused his attention on removing restrictions on catholic participation in the governance of the island. He desperately wanted to create opportunities for catholics to attend colleges and assume positions in white collar positions. He also sought an end to laws that prevented Irish Catholics from owning something more than subsistence farm properties.

O’Connell was a forerunner of Martin Luther King and Mahatma Gandhi. He believed in non-violence and the need to follow the letter of the law, even when he disagreed with the impact of that law. He sought change through a peaceful process and when the English passed a law curtailing his ability to assemble a congregation of one million Irish catholics pressing for liberation, he followed the law and called off his planned convocation. Disappointed followers lost faith in the aging O’Connell’s leadership and splintered into more violent factions, e.g. the Finians. Uprisings and guerrilla warfare would dominate the century ahead. We can find the names of Irish cousins in the headlines of those ‘risings.’

O’Connell’s efforts and the growing optimism of Irish catholics in the 1830s came to a tragic close in 1846. It is at this point that we find our Irish ancestors pressed to stay alive. From 1845 to 1852 the people of Ireland suffered through the Gorta Mór, the Great Death. Known historically as the “Potato Famine” the disaster was far more than a hardship brought on by a failed crop. The name is a misnomer meant to gloss over the fact that the British government earnestly engaged in a well documented genocide on the island.

Historians in the past several decades have uncovered a plethora of documents and evidence that Parliament was engaged in economic practices that killed more than a million people and sent another one million into exile. The English intent was to put to rest, once and for all time, the centuries of dissent and rebellion that had deterred the English protestant’s effort to colonize the Emerald Isle. The potato famine was real, as was the rural Irish family’s dependence on the tuber. On a small plot of land a farm family could raise enough taters to pay rent and feed the family. It is estimated that the average Irishman ate as much as ten pounds of potatoes in a day. But the failure of the crop over the years was not the sole cause of the Gorta Mór.

Unable to pay rent, many small farms owned by Irish catholic natives were lost to the large protestant plantation holders. Those farmers were then driven from their homes. The homes were destroyed to prevent squatters from moving in. The rock was removed to make more walls. The streets of the cities and the pathways leading to them were littered with the bodies of those too weak to walk any further.

In 1847 the Poor Law sought to resolve a growing problem in Great Britain. The number of poor starving Irish men and women was overwhelming the countryside. A million or more starving peasants had died. Millions more were living in squalor on plantation lands. They had been denied the right to own land for centuries. Their properties had been wrongfully seized, taken from them by the English plantation owners in the name of a protestant god and civilized Englishman. The problem was compounded by an economic policy put in place by Charles Trevelyan, minister of government relief to the island.

The records of Parliament for the time of The Famine have been well researched in recent decades by scholars in collegiate settings. The literature revealing the truths of what happened to Ireland in the mid-century is now well documented. The English were seeking to rid themselves of the poor Irish catholic peasants, once and for all. Tired of Risings (rebellion), tired of criminal conduct, tired of Catholicism and all the pain and frustration that came with governing a destitute and unruly land, the British sought to drive the Irish to death or out like lemmings into the sea.

The effects of the famine were avoidable. Certainly, the potato crop failed, and the potato was a staple in the peasant family’s diet. But to assume that the potato was all that would be found on the island is absurd. Trevelyan believed in two precepts that drove his managment or non-management of the crisis: laissez faire capitalism and a free market. Ireland was an agricultural mix of crops and livestock. The records show that the British capitalist was exporting commodities, produce and livestock, to the world markets in record numbers during the time of The Famine. Food was leaving the island on board vessels for foreign ports while the peasants starved at home. The matter was actually discussed and debated on the floor of Parliament. It was a capitalist system; the one percent grew wealthier and the peasants of Ireland paid the price.

The Poor Law sought to move the expense of keeping the peasants alive onto the backs of the landlords. Workhouses had been established to house the peasants in enclaves found in counties and cities across the land. The workhouses were often the last stop for a person bound to die. Disease spread among those living in poor houses and took a toll on life equal to the famine itself. Landlords were taxed in British pounds per people found residing on their property.

Shrewd landlords ran the numbers through their books and found it was cheaper to pay the passage of a person to America than to pay the tax to the Crown. The only hope for solvency for the landlord was to reduce the number of destitute on their estates. The Poor Law forced landlords to evict peasants. Humans were forced to march from their shabby sheik bedrooms across paths leading away from the plantation home, to nowhere. Some landlords found what they considered a more humane method of disposing of the downtrodden: Put them on a coffin ship and send them to America, Canada, Australia, some colony or land willing to accept the street urchins and crusty farm families.

The moral argument was simple: it was far more Christian to export the peasant than to evict them with no place to go. Eviction simply dumped the population out into the British owned countryside of Ireland. The land was already overpopulated, crawling with these “wretched, less civilized, less than human beings.” Why not export them? It was cheaper to pay the four pounds passage out of the country for one peasant than to support that person in a workhouse for a year.

When I first encountered the research related to these events, I was shocked and viewed the author’s efforts as sensationalism meant to sell books. As I dug deeper into the stacks, checked the credibility of authors (plural) and the collegiate institutions responsible for publication I realized the full depth of the tragedy. The Irish genocide was real. The deaths were intentional and profit grabbing glossed over. The efforts were the subject to discussion found in the annals of Parliamentary history. Look it up. The evidence is there and widely accepted now as true.

So the question has been answered: How did the poverty stricken, starving Irish peasant afford passage to the North American continent? Landlords may have paid the expense to simple rid the island of our ancestors.

One cannot assume that Ed Hughes was living in poverty or starving when he emigrated (left Ireland). As I write this paragraph in March of 2021, I have found little evidence regarding the lives of any of our Irish ancestors including the families of Hughes, Dooley, Mahan, Byrne, Banks, Fitzgerald or Mulvanney. If the immigrant in our family came from a rural area the likelihood that they came from a British Plantation increases. Ed Hughes appears to have been a Dubliner. The stories, the oral history handed down, depicts him as a ‘boxer’ or ‘fighter’ appearing in the ring in arranged fights at festivals and stadiums. In all likelihood, the bouts were a side job for Edward and his reward for enduring a battle were small. We know even less, in fact nothing at all about his cousins, in-laws, neighbors and friends.

The cost of passage for one fleeing to Nova Scotia or the American east coast was 4 pounds 10 shillings, on average, for each year between 1838 and 1872, Found among the Minutes of the Fressingfield Suffolk Parish Meeting in 1837 is a reference to that same sum for passage to the states. The average annual income for the Irish farm laborer was 30 pounds 3 shillings in 1835 and a little less than that (29 pounds 4 shillings) in 1850. These stats are found in Williamson’s Research in Economic History – The Structure of Pay in Britain. Doing the math: The cost of Ed’s journey to America, for himself alone would be 13.8 percent of his annual income. That he was a successful farmer in McHenry County has already been illustrated. Ed may have been able to afford his own passage to the states. There is no evidence indicating that Ed or any member of his party, arrived as Irish slaves or as indentured to a benefactor.

Per my father’s memory, Edward Hughes boarded a ship from Dundalk, 50 miles to the north of Dublin, in the 1840s. Records do corroborate this oral history. Edward was roughly 35 years of age when he left Ireland and stepped through the immigration lines entering America. This was 50 years prior to the establishment of immigration offices at Ellis Island. There are records indicating that an Edward Hughes and wife Anne arrived in New York in 1842. The names were common Irish names and there are multiple people with the name. Edward Hughes, John Mahan, and the Dooley sisters moved freely from New York City to Townsend, New York (near Niagara Falls) and the Midwest in short order. A joint venture creating tubing on the whitewater of the Niagara River was a colossal fail.

Census records of Hartland Township, McHenry County, Illinois, reveal that Ed was doing just fine as a farmer once he settled in there in 1850.

This information is about all I have in terms of locating Edward’s parents. Suffice it to say, a check of parish birth records was of little help. There were four Edward Hughes children identified in one Dublin parish alone in 1810. The nation of Ireland and the Catholic Church make continuing improvements in their online archive services to genealogists and perhaps further evidence will surface. As for now, we are serving full Irish (bangers, rashers, farl and mash) in the other room if you would like to join us.

Happy St. Paddy’s Day!

For more about our Irish Ancestors follow these links in My Father’s Tree

Generation 3: Lebanon Smith (1883-1972) and

Mary Hughes (1885-1979)

Generation 4: The John Benedict Hughes Family

Generation 5: Bernard Banks (1828-1858) and

Catherine Burns (1833-1908)

Generation 6: Edward ‘Jack’ Byrne (1801-1854) and

Margaret Mulvaney (1801-1876)