Gen 3: Lebanon Smith (1883-1972) and Mary Hughes (1885-1979)

My Father’s Parents: Leb lived in West Frankfort IL and Dillon MT. Leb and Mary lived in Devils Lake ND, Neilsville WI and Eyota MN before retiring to Auburn, Alabama.

My father’s parents, Leb and Mary Smith, lived a long way away in Eyota, Minnesota. My earliest memory of my grandfather dates to a Christmas vacation in 1955 or so. We were in dad’s recently purchased Studebaker Champion. It was a cool looking car, a throwback to the Buck Rogers Spaceship. Think Flash Gordon. The car had an iconic nose cone, like the early fighter jets. Think Madonna’s left boob when she was wearing traffic cones for boobs in her stage act. I think the car reminded my dad of his days in the Army Air Force.

My father’s parents, Leb and Mary Smith, lived a long way away in Eyota, Minnesota. My earliest memory of my grandfather dates to a Christmas vacation in 1955 or so. We were in dad’s recently purchased Studebaker Champion. It was a cool looking car, a throwback to the Buck Rogers Spaceship. Think Flash Gordon. The car had an iconic nose cone, like the early fighter jets. Think Madonna’s left boob when she was wearing traffic cones for boobs in her stage act. I think the car reminded my dad of his days in the Army Air Force.

The Studebaker, with my sister April and I in the back seat, headed down a state highway toward Eyota MN when good things went bad. A blizzard hit us hard, visibility was shrinking, and a glaze of ice was hiding just under the fluff of innocent looking snow. Dad lost control of the vehicle and we careened into a ditch. Good Samaritans with trucks and chains got the car back on the highway. It occurred to my young brain that we had what could be considered a brush with death. One minute I am here and poof, I am gone. Poof! Standing before God trying to explain why I didn’t eat my broccoli and God responds:

“Don’t worry about the broccoli, kid. That was my son’s idea. He thought we needed a test of your obedience to your parents. I didn’t really expect any child to eat that stuff when the guys in our lab invented it.”

It was a frigid Christmas in Eyota, and the snow was deep outside the two-story wood frame farm house on the edge of town. A wood burning stove served double duty as a source of heat and as an oven for preparing meals. Square holes were cut in the flooring of the upstairs bedrooms and iron registers put in place to allow warm air to rise through the first-floor ceiling to provide some minimal warmth on frigid nights on the second level. Modern conveniences were hard to come by for a hard scrabble farmer, which is what Leb was and had always been.

Leb’s one toilet was an outhouse, fifteen fast steps from the backdoor. I preferred to stay under the comforters in the chilly upstairs bedroom. I wasn’t going to risk frostbite outside. I feared I would be found frozen to the toilet seat in the morning if I sat too long, in the dark of night, in that outhouse. So, I usually ate an early supper or skipped the meal entirely if I could and ignored the bed pan tucked under a chair in a corner of the room. The bed pan came with instructions: “Please empty into the latrine behind the house each morning.”

My grandfather walked me outside to show me his sheep, the cattle and a few chickens. Vaporous clouds escaped the mouths of each critter as it took a shallow breath and exhaled. He pointed to the outhouse and apologized for not having installed indoor plumbing just yet. As he sucked air through his tobacco pipe, I noticed that he held it with only one half a hand. Several of his fingers appeared to be missing. They were stubs of their former selves. He noticed that I was carefully studying the nubs of flesh and bone.

“Cut them in a damn drive chain on a farm some time ago,” he mumbled. I marveled at the fact that he was still alive. In the middle of my awestruck moment a large goose scurried by, chased by a ram and several chickens.

“That damn goose hasn’t long too live. Christmas dinner you know.” The goose farted a terrible blast, as if to comment on Grampa’s death sentence. My grandfather waved his hand, clearing the air a few times and mumbled, “This too shall pass.”

Many years later, in my role as a school administrator, I would attend long and laborious school board meetings. To escape near death experiences at the hands of a few patrons, I would often picture my grandfather, his pipe in hand and the “damn goose.” As folks droned on into the night, I would remind myself: “This too shall pass.” I called this ‘The Fart Theory’ in courses that I taught on Educational Leadership.

Of all the teachers and professors, I have ever met I have yet to find one whose education matches that of the sage who was my grandfather, Leb.

Grandmother Mary would bound from the house moments later, pounce upon the goose, throttle it by the neck, grasp the legs in one hand, and with an axe in the other hand, forcefully throw the startled bird onto a tree stump and quickly behead it. It was all done in one momentary swoop, a bloody ballet. The headless corpse then ran about the yard for a few seconds escaping Grandmother’s grasp. The neural network in the spinal column operated on motor memory just long enough to entertain us and exhaust Granny. Grampa was chuckling in a careful manner.

That Christmas trip constituted our last journey to Eyota. Leb and Mary loaded up their family truck with their belongings and drove through West Chicago on their way south to Auburn, Alabama. Grampa had picked up spare change as a part time trucker hauling hay or critters to market in Minnesota. I remember when his delivery truck arrived in our front yard on Geneva Street. It was Leb’s version of a covered wagon, stacked high with sofas, tables and chairs and a mattress or two. Everything Grampa and Gramma had accumulated in life was on that flatbed. It was a scene made famous by the Beverly Hillbillies in a 1960s hit comedy series. My grandparents stayed long enough to sleep, grab a meal and go. Several days later they would settle into their cottage on Brookwood Drive, Auburn, Alabama, in what amounted to the backyard of Bill Smith’s home on Bowdon Drive.

One can’t really know my own father without knowing his father, Leb. Dad loved talking about grampa and the time he spent as a young man growing up in Eyota. Leb loved my father but only told him so once in life, and it was done with non-verbal communication. It was a rare poignant moment. JD (dad) decided to join his brothers, Bill and Bob, in the military service of our country. WWII was raging across the globe and Dad wanted to learn to fly and be the one to bomb Hitler’s home. On his last weekend before basic training he stopped by the Eyota homestead to drop off his personal belongings from college and see his folks. When it came time to leave the three said their farewells. Per my father’s story, Grampa shook dad’s hand and wished him well. Dad waved goodbye and his parents disappeared behind the house. Dad remembered an item he needed to take with him and slipped quietly around the back side of the house to retrieve the item. He found his father in tears. Dad told me he pretended not to see Leb, retraced his steps and left quietly. It was how men conveyed affection. My father learned the lesson well. Expressing love in words never appeared easy for men coming out of World War II, my father included. But I and all others who descend from these WWII veterans know full well that our fathers loved us. It would be my Uncle Bill who taught me that it is healthy for men to experience and share emotions, to embrace and say, ‘I love you,’ if it is genuine.

Leb Smith had a tough go of it in life and never complained, as far as I could tell. He was laid back in attitude, long before being laid back was fashionable. It may have been the daily dose of medicine he took. Gin had a healing effect and a shot or two a day, for medicinal purposes only, helped him cope with whatever ailed him. Some ailments were obvious like the fingers missing from his hands, or stubs of fingers that remained. Too many conveyer belts and miscues with saws had taken their toll on his aged, varnished hands.

Leb left school with a fourth-grade education and that was a new low for Smith kids over the course of our first three hundred years in the New World. Many of his ancient ancestors benefitted from tutors, private school education and a better academic preparation than Leb would acquire. But if street smarts were becoming important on the Great Plains, he had them in spades. The places he called home in southern Illinois, Montana and the Dakota Territory just didn’t have streets, per se. A buffalo trace provided enough of a path if one knew the migration patterns of the majestic beast. Following an Indian Path could lead to trouble as Custer was apt to point out in his final soliloquy: “I should have become a haberdasher.”

I have always been fascinated by the fact that my grandmother, Mary Hughes Smith and her sister Frances each taught in their own one room schoolhouse, just off a Sioux hunting trail. I would shutter when she talked about taking her students to the cellar to hide when the Sioux would pass by the school on their way to or from a hunt. Although it had been some decades since the New Ulm Massacre, I think Dakota pioneers still conjured up images of bloodshed and hid in cellars for a false sense of safety.

My classmates and I participated in a similar drill in the late 50s and early 1960s during the height of the Nuclear Arms race. A high-pitched alarm would pierce the school hallway. The community siren would scream out with a frenetic energy that told us we were all about to die. The teacher would shout, “Duck and Cover!” We would hit the floor, throw our arms over the tops of our necks and heads, curl up into a fetal position and kiss our ass goodbye.

I think we lost more classmates to injury than Granny ever did to the Sioux. I was stunned however, to discover how many of my ancestors did die in skirmishes with the Native Americans who were seeking to preserve their homeland.

Leb found it necessary to leave public school and provide for his family. He never knew his oldest brother, Peter Smith. Pete passed away at age 12 in 1880. Peter was well on his way to becoming a valuable helpmate on the farm and in the mines when he died. With only one other son, William Davis Smith, Leb’s father was short on boys in his growing family. When Leb was born in 1883 he quickly became the spoiled brother of five older sisters, some of whom never really knew him. As an example: the age difference between Leb (b 1883) and his oldest sister Nancy (b 1869) was fourteen years. She was, by pioneer standards, a young woman before Leb ever developed a capacity to remember childhood.

Lebanon Faris Smith sometimes spelled ‘Ferris’ was born in West Frankfort, Illinois on June 3, 1883. His parents were James Monroe Smith (1846-1910) and Jane Stilley (1844-1927). When Leb was born Jane let her husband know that Leb would be the last of the litter. Eight kids would be enough. But she was wrong. Records show that a child, Gracie, was born three years later in 1886. But, sadly, Jane turned out to be right when the baby failed to survive. That happened all too often in history. Leb would always be the youngest of the litter but mother Jane would always be a care provider to her children and grand children as we shall see.

Lebanon Faris Smith sometimes spelled ‘Ferris’ was born in West Frankfort, Illinois on June 3, 1883. His parents were James Monroe Smith (1846-1910) and Jane Stilley (1844-1927). When Leb was born Jane let her husband know that Leb would be the last of the litter. Eight kids would be enough. But she was wrong. Records show that a child, Gracie, was born three years later in 1886. But, sadly, Jane turned out to be right when the baby failed to survive. That happened all too often in history. Leb would always be the youngest of the litter but mother Jane would always be a care provider to her children and grand children as we shall see.

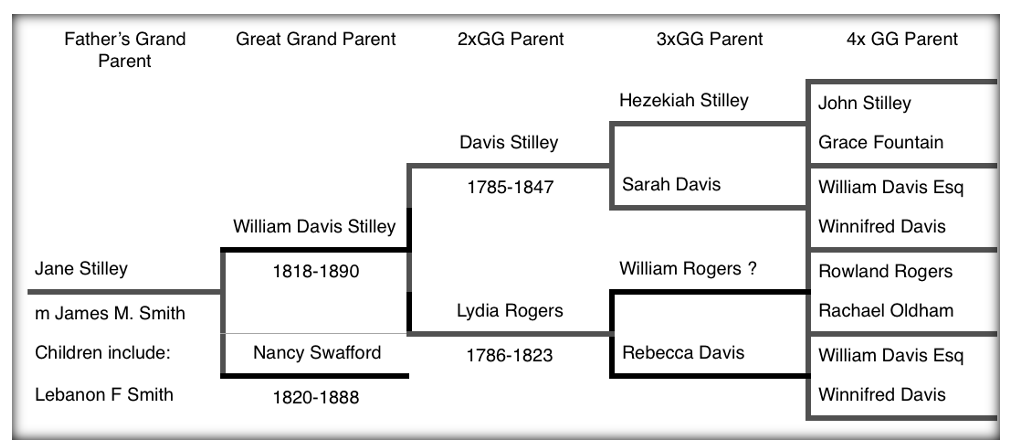

The name William Davis Smith (1877-1940) provides a hint that becomes useful in tracing a rich history in our family lineage. ‘Davis’ is a surname (last name) in our Smith line of ancestors. It was a common practice to bestow a family surname on a child as a first or middle name. Jane Stilley’s father was William Davis Stilley and her grandfather was named Davis Stille. Jane’s great grandparents were Sarah Davis and Hezekiah Stilley (1763-1840). Sarah was the daughter of William Davis of Hyde County, North Carolina (d 1802). We will explore the roots Sarah Davis and Hezekiah Stilley bring to our tree in greater detail in a later chapter. For the moment let me offer this tidbit of information: Davis family members were among the first pioneers to settle Maine, Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky, Indiana and Illinois. Stille and their ancestors were the first settlers in New Amsterdam (1626) and New Sweden (1638).

Leb and Mary Smith’s home in Auburn, Alabama c1970

Pedigree Chart 2: Jane Stilley’s Roots

The spellings of surnames changed over time: Stille to Stilley, Davies to Davis. It was all about assimilation: fitting in, becoming American.

Leb and Davis Smith worked the family farm in Franklin County IL until the notion came upon them that they should head west to Idaho and Montana. At age 21, Leb road the trains to DuBois, Wyoming. The rail line provided tourists with a route to Yellowstone, the nation’s first national park, created in 1872. It also provided ranchers with a railway to ship cattle to stockyards in Chicago and Kansas City. From DuBois the wannabe cowboy grabbed a stagecoach for the long ride across the very desolate lunar landscape of southern Idaho to Pocatello.

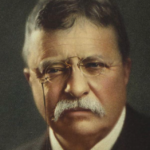

Teddy Roosevelt was in his third year as President of the United States when Leb took up the life of a cowboy. Roosevelt had already become legend as a Rough Rider. The time the President spent in North Dakota as a youth enhanced his image as a rough and tumble guy. Roosevelt identified with the herdsman of the Great Plains, the cowboys of the Wild West. The cowboy, he wrote, “does possess, to a very high degree, the stern, manly qualities that are invaluable to a nation.” His articles about frontier life, written for national magazines, and three published books caught the attention of young men like Lebanon Smith, a man who could barely read the words but understood the message. Teddy and Franklin Roosevelt share a several times great grandfather with my brother-in-law Keith Wetherell and his children, Mike and Treva. They all have Delano blood in the gas tank. We can dig deeper into that piece of family history when we join the Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock. Yep, there are pilgrims in this family tree. They could be a pious, intolerant bunch. We have Quakers also. Well, never mind. I can visit that subject later.

Teddy Roosevelt was in his third year as President of the United States when Leb took up the life of a cowboy. Roosevelt had already become legend as a Rough Rider. The time the President spent in North Dakota as a youth enhanced his image as a rough and tumble guy. Roosevelt identified with the herdsman of the Great Plains, the cowboys of the Wild West. The cowboy, he wrote, “does possess, to a very high degree, the stern, manly qualities that are invaluable to a nation.” His articles about frontier life, written for national magazines, and three published books caught the attention of young men like Lebanon Smith, a man who could barely read the words but understood the message. Teddy and Franklin Roosevelt share a several times great grandfather with my brother-in-law Keith Wetherell and his children, Mike and Treva. They all have Delano blood in the gas tank. We can dig deeper into that piece of family history when we join the Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock. Yep, there are pilgrims in this family tree. They could be a pious, intolerant bunch. We have Quakers also. Well, never mind. I can visit that subject later.

Leb joined his brother Davis in Pocatello, Idaho and was soon employed at the Reno ranch. The Reno Ranch wasn’t just any ranch out west. For whatever reason, destiny found our guys working on the 2200 acre spread of one James H. Brady. Brady, a Leavenworth Kansas College Grad had taken his earnings as a real estate salesman to Idaho in 1895 and purchased enough land to create his ranch. Leb and Dave herded cattle and sheep for the man while Brady established himself as the state’s governor. Brady lost his reelection bid but stayed in politics and later earned a seat as the United States Senator from Idaho in 1913. Leb and Dave were long gone at that point in time. Leb’s spurs from that adventure sit on a shelf above my desk here in the Northwoods of Wisconsin. Grampa had countless stories to tell about his life as a cowboy.

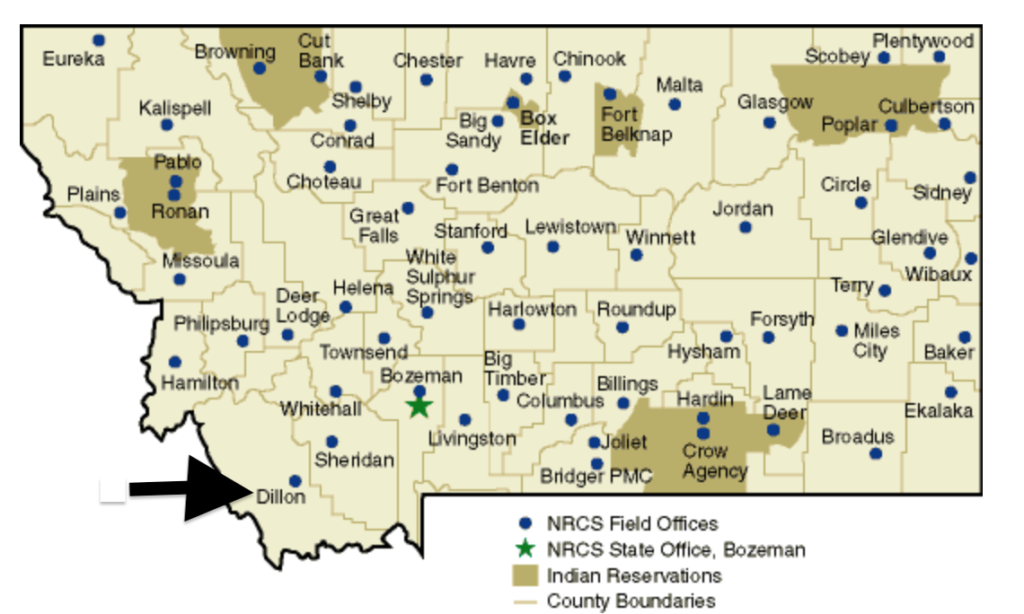

Dad recalled that Leb and Davis spent some time herding sheep in the Beaverhead River Valley of Dillon, Montana. It was during that time in Montana that Leb learned to pick up a rattle snake, spit tobacco juice in the eyes of the serpent and use it as a walking stick. I was glad that we were hard pressed to find a rattlesnake on his farm in Minnesota in 1955 or his back yard in Auburn, Alabama in 1962. I did not want to test the accuracy of his story or spoil the magic his stories created.

Dad recalled that Leb and Davis spent some time herding sheep in the Beaverhead River Valley of Dillon, Montana. It was during that time in Montana that Leb learned to pick up a rattle snake, spit tobacco juice in the eyes of the serpent and use it as a walking stick. I was glad that we were hard pressed to find a rattlesnake on his farm in Minnesota in 1955 or his back yard in Auburn, Alabama in 1962. I did not want to test the accuracy of his story or spoil the magic his stories created.

At some point in time in his days as a cowboy, it was Leb’s job to ensure that a particular bull did not enter the pen with the cows except when dictated by management. Leb did his job, the bull never got close to the cows and the bull only grew more frustrated. The bull’s snorting and macho displays of affection became constant. But the bull could never succeed in getting what he so desired. One day, however, a twister came through the valley. Leb and Dave took shelter and survived the storm. As Leb reported it to me: “The twister lifted that damn bull up and carried that critter over the fence into the field with the cows. The bull was stunned by his good luck and once he recovered from the shock, he was soon making his rounds with the ladies.” According to Grampa, they had quite a few calves that spring that were not part of the management plan. In the years I lived in Montana we never once heard of a twister, but again, I did not want to research the history of the state’s weather conditions. There are some things in our family history that should remain part of the lore and held as ’truth’. “It’s a good story. Write it down,” my father would say, stealing a quip from his favorite Irish comedian, Hal Roach.

My Grampa and Dave did eventually leave the Reno ranch and separated for a moment in time. Leb worked alone one bitter winter at a grain elevator in Dillon, Montana at the foot of the Pioneer Mountains, in the Beaverhead River Valley.

It is a spectacular setting in which to live. But without modern conveniences it had to be a challenge to get through a long winter. Dave headed east into the breaks of the Red River Valley of North Dakota. North Dakota had acquired statehood in 1889. In the spring of the year Leb retreated from the isolation found in the remote ranch town of Dillon and headed east to find Dave conjuring up their next ‘Excellent Adventure.’

I have often wondered how people could find one another back then, without telephones, cell phones, GPS tracking devices, Skype, email, Facebook. The old U.S. mail system must have been effective in keeping our predecessors organized and in touch. Grampa found Uncle Dave in Devil’s Lake, North Dakota. The year was around about 1908.

Much of what I have learned about Grampa was gleaned from my father, either in conversation or in a narrative he provided my sister Shelley who had the intelligence to ask Dad to record his family stories later in his life. When telling a story Dad had a habit of licking the smoke from his Corona Cigar or an old tobacco pipe, he had picked up on his summer travels. He would fidget with his matches in an almost constant effort to keep the tobacco burning. You could tell when a story was going to get some embellishment when a twinkle would appear in his eyes.

Great Uncle Dave Smith had located a large tract of wheat fields that could be rented from a Swede by the name of Carlson. The brothers were right at home living among the Scandinavians of the Dakotas and Minnesota. Their mother, Jane Stilley, was of Swedish and Dutch descent. The Stilley family was originally from the islands in the Gulf of Bothnia, north and east of Stockholm, Sweden circa 1600. Olof Stille escaped the wrath of an aristocratic land lady in 1638 and ventured to Christiana, New Sweden. (That sounds so much more pristine than saying Hoboken, New Jersey). You will find the tale of Olof Stille the swash buckling farmer turned Chief Justice, lodged in another chapter.

Jane Stilley Smith lost her husband, James Monroe Smith, in 1910 and came up from Southern Illinois to live with her sons and help in any way she could. James had taken leave of his farm in West Frankfort to head down the wagon trail to the crossroads village of Anna, Illinois. It was there that he died. He was helping one of his girls in the construction of a new homestead. A tree that he was felling dropped on James and crushed him. Such trees are called “widow makers” for a reason and Jane was made a widow. Her sons were more than happy to have her company in the desolate Dakotas.

It was on the prairie of North Dakota that Grampa met my grandmother, Mary Hughes (1885-1979). She was born and raised in Tyndall, Bon Homme County, South Dakota. Mary and her sister Frances were among the first women to graduate from the South Dakota Teachers College in Brookings. Mary’s first job as a teacher was in a country school in the ranch community of Devils Lake, ND.

Gramma Mary Smith was 100 percent Irish; a combination of Hughes, Byrne, Dooley, and Mahan bloodlines. Throw in the Banks and Fitzgerald clans and you have the makings of an Irish regiment. Her Irish heritage alone causes me to think of myself as an Irishman. My father who always believed his Smith ancestors were English never owned that English heritage as his own. He was enamored with the idea that he was at least half Irish, and that made him all Irish, seven days a week. As it turns out, in the years since my father’s passing, I have found much evidence that dad was more Celtic than he ever imagined. Keep in mind that Celtic blood can include Scotch, Welsh, Briton, Germanic, Cornish, Fir Bolg and more.

Wheat prices during World War I were high enough to allow Leb to put together a nest egg that allowed he and his newlywed wife to afford 440 acres of farmland in Neillsville, Wisconsin (See left).

Wheat prices during World War I were high enough to allow Leb to put together a nest egg that allowed he and his newlywed wife to afford 440 acres of farmland in Neillsville, Wisconsin (See left).

In preparation for winter the family removed manure from their cattle pasture and packed the sides of the house with the crap to slow the penetrating winter wind. It provided some insulation against the bitter cold so popular here in the Northwoods of Wisconsin. If the price of corn were too low to turn a profit, Leb would use the ears as a heat source in his wood burning stove. In the Spring, the manure would be peeled away from the Smith’s home and shoveled onto their garden plot. Leb and Mary were truly living off the land in the cycle of life, making use of anything and everything that could get them through the day and year.

Leb counted on his kids to chop the wood for heat and cooking. Leb’s daughter, my Aunt Marge Smith Jacobs, was not about to be left out of chores. She insisted on chopping right alongside her younger brothers: Bob, Bill and Dad (as he grew older). This photo of their primitive home in Greenwood WI is 100 years of age! It has been subjected to a few different modern-day apps to look as it does! Marge (to the front and center of the cabin photo) along with two of her brothers (to the right) are cutting and stacking wood.

Leb counted on his kids to chop the wood for heat and cooking. Leb’s daughter, my Aunt Marge Smith Jacobs, was not about to be left out of chores. She insisted on chopping right alongside her younger brothers: Bob, Bill and Dad (as he grew older). This photo of their primitive home in Greenwood WI is 100 years of age! It has been subjected to a few different modern-day apps to look as it does! Marge (to the front and center of the cabin photo) along with two of her brothers (to the right) are cutting and stacking wood.

We have that below zero cold today as I write, and I am grateful there is enough fuel in the tank to keep me warm. I would hate to rely on Murphy, my Golden Retriever, for the organic materials needed to wall the foundation of my house in dung. Although the dang turkeys that come through here might be leaving enough scat for me to… No, never mind.

Rumors that Wisconsin had mild winters prior to the era of the Green Bay Packers are unfounded. Legend has it that Packer Coach, Vince Lombardi, wanted to brand his team as a hearty bunch of Northwoods ruffians who would gladly pound any man into the ground if it meant victory. To embellish that image Lombari demanded that God give the state bitter winters filled with deep snow and freezing temperatures. Eventually God gave in to Lombardi’s demands and the Ice Bowl was created. In return, God was given front row seats and eventually a skybox at Lambeau Field.

What memories do you have of family and friends that you could share? You can expand this volume of Smiths by adding your own reflections. Think about it…. “Write that down….,” my father would say, doing his best impersonation of Irish comedian Hal Roach.