THE BURNT STATION MASSACRE

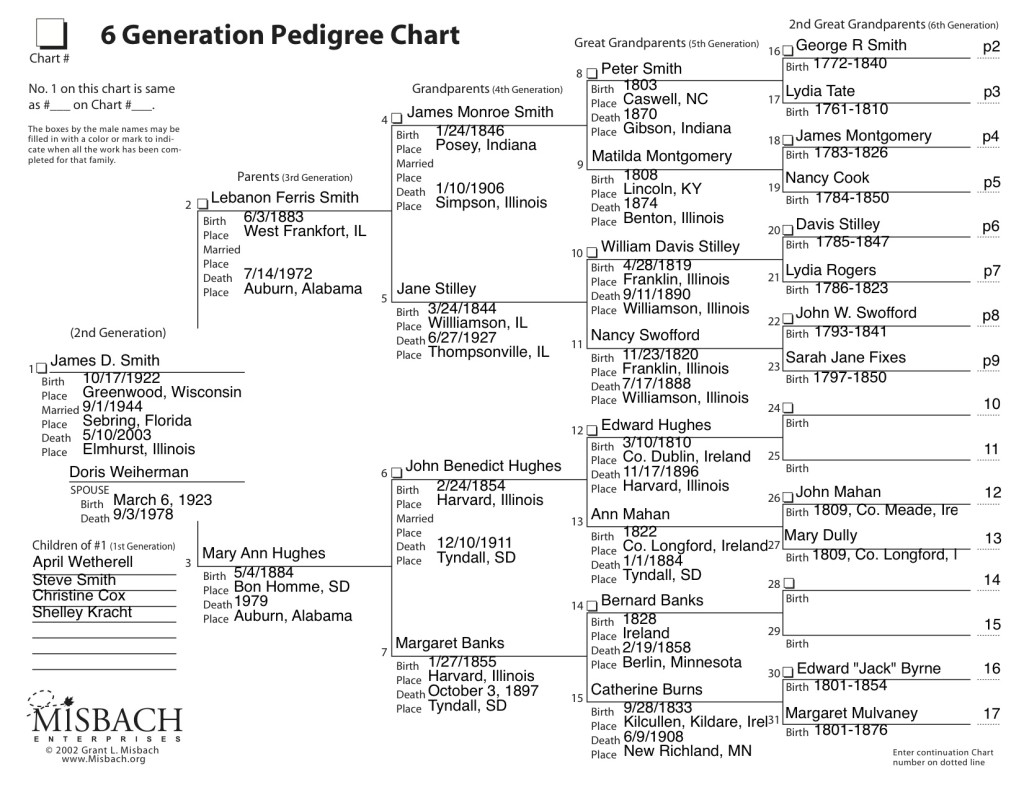

SMITH FAMILY TREE: Kincheloe, Simpson, Davis, Bland, Cox, Wickliffe, Floyd, Rogers

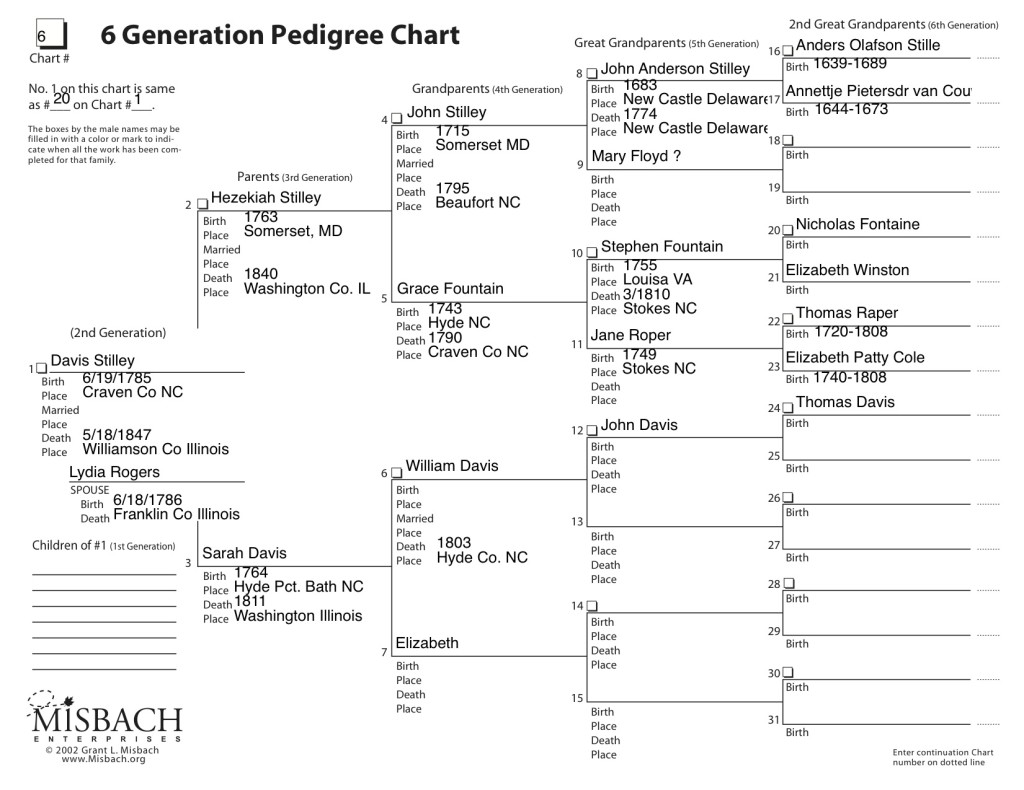

WHITTINGTON TREE: Polk

The Kincheloe homestead was a collection of cabins within the palisade walls of what constituted a “fort.” It was called Kincheloe Fort (aka Kincheloe Station), and was established in Jefferson County (present day Nelson County), Kentucky. There were a number of similar forts or stations positioned across Kentucky. One hundred and eighty years after the settlement of Jamestown VA, a pioneer still had to have a strategic plan for the defense of their home and family. Essential to the defense of the Kentucky pioneer was this system of small forts or stockades, similar to the Pilgrim structure in the original Plymouth Colony. When one station came under attack, the men of other forts would come to their support. Settlers knew the system and in which direction to run for help or to help. I don’t know if the pioneers ever practiced as we presently do with our various drills in schools: fire, tornado, intruder, toxic waste or nuclear war drills, but I am certain they knew the system and had their own way of sounding the alarm.

The fort stood along Simpson Creek. The creek was named after the Simpson family found in the Smith family tree. One of the Simpson girls, Jemima, had married Peter Smith of Round Hill fame in 1765. The Simpsons were descendants of the same Simpson family found in Peter of Yeocomico’s neighborhood on Bull Run (Clifton, Fairfax Co VA). Many of Peter and Jemima Smith’s sons resided in Kentucky in 1781. The Kincheloe, Simpson, Smith, Boggess and Davis families had all intermarried at his point in our nation’s history. We were one big happy family in need of a fresh network of unrelated neighbors with whom we could breed and refresh the gene pool before disaster set in, including the usual British problems related to dental hygiene.

The Kentucky Historical Society established the exact location of Kincheloe Station in Nelson County, one-half mile south of the Spencer County line, situated between the east and south forks of Simpson Creek, two and one-half miles downstream from Bloomfield, Ky. The society even marked the location for the rest of us so we can saunter out there with a picnic lunch and reminisce about the time great great grampa was scalped by the tribe, granny had her baby ripped from her arms and other horrid details that surface in these massacres. The society drove an iron stake into the ground at the site of the fort and attached a metal tag marked “1782 K.E.” The highway marker is set up along Highway 62, directing us to Kincheloe. The site is a good 900 yards northeast of this marker, and east of Creek Branch. I can’t make light of this effort. Several of my ancestral families died one night in a brutal massacre, creating a bloody page in our scrapbook.

Kincheloe Station was built in a field of about ten acres, on a high spot near a spring and out of gunshot from any enemy that might position itself further up on the adjoining hills. The hills still surround the valley on three sides. They haven’t moved. Although Mr. Peabody and his coal company did move the land away from the Smith homesteads down the road in Paradise. From a point on one of these hills a sentinel had a plain view of the entire valley and could provide a warning call to friends and family; (mostly family, because many of these small Kentucky pioneer villages were clans of intermarried refugees from the hills of Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia or from Pennsylvania off to the northeast). In this particular fort, on this particular evening, we find members of my ancestral family tree (Davis) hunkered down with members of my wife’s Whittington family tree (the Polks) during what was a tense week in the Blue Grass paradise. Other occupants include Osborne Bland and his wife, William Harrison and his wife and children, a Mrs. Ash with her young son Benjamin. The Ash family is included in the Fleming tree, into which some Smith daughters married.

The fort was originally established by Captain William Kincheloe and occupied by several families. Records indicate that Kincheloe had moved his family from the fort and migrated about 8 miles to the south and east to Chaplin Fork in the late Autumn of 1781, prior to the attack at Kincheloe Fort. Another early resident and relative, Arrington Wickliffe had also lived for a short time at Kincheloe Fort but had moved on, further into the wilderness in the fashion of Daniel Boone. Note that the name Arrington Wickliffe is also composed of surnames found in the Bull Run/Clifton VA neighborhood.

A Collins family historian indicates that “there were six or seven families and perhaps about thirty inhabitants occupying the fort at the time of the massacre.” The families that were recorded as present at Kincheloe on the evening of the attack included ten members of the Colonel Cornelius Davis family (his wife, seven children and a slave). Other settlers present were the wife of Captain Charles Polk and her four children, Mr. and Mrs. Thomson Randolph and their four children, William Harrison, his wife and a second woman staying in her home, a Mrs. Ash and her son. To locate these folk in our family tree please click on this link.

There is some confusion when one reads through the literature related to the events that took place. Articles written in the century that followed the tragedy refer to attacks at two forts: Polk Station and Kincheloe. Others believe that Polk and Kincheloe were one and the same fortress. One historian explains the disparity with the simple observation that Kincheloe built the fort on property claimed by Captain Charles Polk. Another fort, Cox Station, was constructed a shore time after Kincheloe and could be found just north of present day Bardstown, Kentucky on the Buffalo Trace. The Cox family in the 1800s descended from Vincent Cox of Yeocomico, a neighbor and relation of the original Peeter Smith (d.1691).

Historians agree that the demise of Kincheloe Fort was tied directly to battles that had been fought in previous days at Blue Licks and Bryan Station. As these two events also involve our ancestors I will provide a summary of events that fed into a tragic page in our family history. I was going to call it a brief summary, but I will leave that for you to decide. Maybe it won’t seem so brief. Certainly bloody.

Blue Licks was one of the last battles of the American Revolutionary War. In fact, it occurred on August 19, 1782, fully ten months after Lord Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown. We have been led to believe that the Revolutionary War ended at Yorktown. It did not. The surrender at Yorktown pretty much sealed the fate of the British but it did not end the war. On the sunset side (west face) of the Blue Ridge the British were intent on maintaining their hold on what would become the Northwest Territory (including Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin). The Brits were still in control of Canada and wanted to maintain possession of the Ohio and upper Mississippi River Valleys.

To accomplish that goal a force of 1000 Natives and British loyalist forces gathered on the banks of the Mad River in Ohio and agreed to attack a patriot fort at Wheeling, (later West) Virginia. But rumors quickly spread that General George Rogers Clark was preparing to launch a major patriot invasion into Indiana and Illinois. British Loyalist forces took a cautious wait and see attitude in their planning efforts. Clark did not attack on this occasion. Instead he maintained his large military forces on barges patrolling the Ohio River, staying mobile enough to respond as needed. Clark’s force was in part raised by Bailey Smith, the son of our Great(GGF5) Grandfather James Smith.

The Loyalists, assuming that Clark was not attacking as rumored, gathered a force of 50 pioneers loyal to Britain, Canadian Loyalists (Tories) and 300 Native Americans; all banded together under the command of British Captain William Caldwell and Pennsylvania Loyalists: Alexander McKee and Simon Girty. The pro-British army crossed the Ohio River with the intent of launching a surprise attack at Bryan Station.

Bryan Station lies 50 miles to the east of Kincheloe Fort. The site today is found in the eastern suburbs of Lexington, KY. This fort was established by the four Bryan brothers of North Carolina on the banks of Elkhorn Creek. It housed forty log cabins, constituting a sizable community for the time and place.

Kentucky settlers got wind of an impending attack and secured themselves within the palisade walls of the Bryan Station fortress. Legend has it that the British Loyalist forces made what they thought was a stealthy approach. Caldwell intended to hold up in the woods surrounding the fort. He assumed his presence and not been detected. He would lie in wait, study the situation from hiding and then launch an overwhelming effort when he had his best opportunity. Caldwell had false information that the stockade housed a larger number of settlers capable of putting up a terrific fight. The pioneers were not idiots. They knew full well the Brits and Natives were out there in the woods and they weren’t there for a Bowling Tournament. The settlers had already sent for reinforcements. But they seriously underestimated the size of Caldwell’s forces.

The pioneers within the stockade feigned ignorance of Caldwell’s presence out there in the woods. While he was busy being ‘invisible’, they went on about their daily routines contributing to an impression that a large population lived within the fortress. Their intent was simple: prolong any impending attack. It was only a matter of time and they knew it. Their survival depended upon cunning and upon those reinforcements. In their effort to appear ignorant of the impending danger the pioneers continued their daily routine of gathering water from a nearby spring, beyond the perimeter of the fort. This was downright dangerous as it required opening the fortress gates and sending folks out alone to toil under the summer sun as they did every day. The water was necessary for drinking, but would also be needed when the attack began. It was common practice for the native warrior to fire flaming arrows into the rooftops of pioneer villages. The woman chiefly credited with organizing the water brigade and making frequent trips to the springs was Mary “Polly” Hawkins Craig (wife of “The Travelling Church” patriarch Toliver Craig, Sr.). The Hawkins family is found within my wife’s Whittington family tree and descends from the seafaring pirates, The Hawkins Group, LLC.

The Loyalist force made its presence officially known on August 15 with the usual burning of the corn field ritual that begins every siege known to man. The perfunctory killing of the livestock followed and added to the message. Twitter feeds were soon going viral: “Bryan station is under siege.” With the settlers outnumbered and confined to their fortress, they could only hope that Colonel Logan or Captain Cox would arrive with military support. Surprisingly and much to the relief of the Bryan population, Caldwell withdrew from the Station after only two days when he learned that a Patriot unit of Kentucky militiamen was on the way. And indeed, help was on the way. His scouts had advised him correctly.

Colonel Floyd, who commanded the Kentucky patriot riflemen had assemble his men and marched quickly to the relief of Bryan Station. Riflemen at Polk and Kincheloe Stations had promptly responded to the call and marched with Col. Floyd to the relief of their neighbors at Bryan Station. The force included about 47 men from Fayette County and another 135 from Lincoln County. The Patriot militia arrived at Bryan Station on August 18. The British forces were gone, the station was secure and it appeared to Floyd that the situation was under control. The question arises: Was Caldwell’s advance on Bryan Station a ruse? Did he feign an attack on one location to draw troops in that direction, only to move more forcefully against reduced forces in another, more strategic location?

Satisfied that Bryan Station was secure, Floyd took his men 25 miles to the north and east to Frankfort, KY, in an effort to contain the escaping Caldwell & Co. and send them in the direction of Logan’s regiment. He received news that the British forces were being contained in the Battle of Blue Licks. He also heard that Colonel Logan was pursuing the Indians with horsemen. Col. Floyd was getting the false impression that everything was under control and his forces no longer needed. Far from it.

Floyd dismissed his men. The Kincheloe and Davis men separated and returned to their homes. Another day, another shilling. The men from Polk’s and Kincheloe’s stations traveled together to where Bloomfield is now located, arriving some time between dark and midnight.

THE MASSACRE OF KINCHELOE STATION

Native warriors were observant and shrewd in terms of military tactics. They knew the pioneer network system of stockades and how the white settler’s response system worked. If you could trigger a response and have militia mobilizing to reach Bryan Station, the Native warrior knew the pioneers would be leaving Kincheloe, Cox and other forts vulnerable to attack. The British Colonel Caldwell knew, as did the native warriors, that one could feign a retreat and draw an overzealous enemy into an ambush. Those two factors created the last great defeat of the American patriot forces in the Revolutionary War, ten months after the thing was supposed to have been resolved at Yorktown. And the crazy thing is that the highly recognized frontiersman, Daniel Boone, knew better. The young whipper snappers with their West Point training pulled rank on his civilian status, ignored his advice that they were plunging into a trap and they attacked at Blue Lick before Logan arrived with support. They plunged their men into a fiasco. Boone and his son followed their orders as required of a soldier, and Daniel’s son died in battle.

Various online histories are in disagreement as to dates and the timing of events. There seems to be a general agreement that the Seige of Bryan Station took place on August 15 thru 17, 1782. The Battle of Blue Lick is dated as August 19, 1782. The Kincheloe Station Massacre is often reported without specific dates. Where dates are given they often disagree with the Chronology of Events as related by those who were alive at the time of the massacre. The most credible date is provided by Colonel John Floyd in his journal, probably titled something like The Life and Times of a Magnificent Man. He identified September 1, 1782. Even this date does not jive with the stories told by survivors. One thing seems certain to me: the history regarding Kincheloe Station is flawed at best. That doesn’t mean it didn’t happen! The circumstances are certainly dramatic enough, but the stories that were told and retold were no doubt embellished and made more horrific each time a story teller sought to up the Shock Value of the details. It would be tempting for me to go into gross detail on the various manners in which our relatives died. Every piece of fiction needs to be more graphic and bloodier than the last. In this age of the Walking Dead, Fargo and Trainspotting you would think I could garner a Pulitzer Prize if I portrayed in graphic detail how folks died. I won’t do it. It can all be found online and I can provide a few links if you insist on reading about the various ways a person can be eliminated.

The long and the short of it is this. The ancestors who rode off with Colonel Floyd in pursuit of Captain Caldwell were depicted as exhausted and slow to arrive home. Cornelius Davis waited for the return of his men from Blue Lick and allowed the families within the stockade to retire for the night while he maintained the perfunctory watch. He had no reason to be suspicious. The latest information indicated Caldwell’s forces had inflicted a bitter loss at Blue Lick, crossed the Ohio River into Indian Territory and dispersed. Caldwell’s manuever had been designed to inflict immediate damage, increase stress among the settlers and perhaps force pioneers to leave Kentucky in the hands of the British. Why Caldwell would think such a thing is beyond belief. From the first days of the British arrival in the New World, be it Plymouth Rock or Jamestown VA, the colonists never retreated from their call to move west. They did move further away from British control.

Beyond the Kincheloe fortress, 17 Natives waited at Dugan’s Spring, a short haul from the gates of the fort. These 17 warriors broke away from Caldwell’s force and, rather than crossing the Ohio River with Caldwell, turned south to inflict damage at several forts. Davis, thinking that he could catch a few winks before sunrise, retired only to expire within moments of lying down to rest. As midnight approached, certain that all were asleep at Kincheloe Station, the natives silently surrounded the perimeter and prepared to attack.

All hell broke loose according to every story teller who was ever asked by the press to recount the tragic events. Radios blared banner headlines. TV carried the gruesome images and the Internet buzz feed was intense. Well… OK… all that stuff never really happened. Authors did pen books and newspaper articles that carried this typical recounting:

So silent and cautious were the Indians that no alarm was given during the night. Just as day began to dawn, Col. Cornelius Davis the sentinel, apprehending no danger, retired from his post to procure a few moments repose. He had been relieved, probably, by one of the Slaves, described as “a large Negro Man”. Col. Davis had just entered his cabin and commenced divesting himself of his clothing. Almost undressed, only his shirt remained on, preparatory to lying down, he heard the savage yells as the Indians sprang from hiding and scaled the Stations palisade. Reaching up, grabbing his rifle, he stepped out of the cabin door and fired at an Indian atop the stockade. The flash of Davis’ rifle revealed his position to the attackers, instantly several fired at him. So close were they that his shirt was set afire by powder flash from the muzzles of their rifles.

The story tellers of the time include Colonel John Floyd (not present, but responsible for investigation and counter attack), Isaac Davis (survivor, age 7 at the time), James Cox (survivor, age 13 at the time) was not a witness but heard the details, Captain Polk’s seven year old son who was kidnapped and dragged away from Kincheloe.

“Wounded, bleeding and his shirt dancing with a light flame, Col. Davis stepped back into the cabin to warn his family, while the large Negro Man tried to keep the Indians at bay.”

Davis stepped back outside and faced his death trying to protect his family. In each of the stories a common thread is found. Colonel Davis and the ‘Black Man’ are heroic to the end. The Black Men seldom have names. They are Black Men. The Natives are conniving, vicious barbarians. Real bastards of the worst sort: He Devils bound for hell, for sure.

The Indians soon controlled the grounds within the station. Their surprise attack had succeeded. Only two defenders had offered initial resistance and both men were dead.

“The savages made short work of the others who awoke in the midst of a living nightmare. Their worst fears had become a hideous reality. The remaining family units barricaded themselves inside their crude log cabins, which proved poor refuge against so many Indians.”

“One savage shot through a crack between logs and killed Mrs. Thompson Randolph as she lay in her bed. Her husband fought the braves after they broke into the cabin. He grabbed up one of his infant children in his arms and somehow managed to break free, carrying the child in one arm and fighting with the other. He may have gone out through the roof, since it was composed of split boards held down only with weight poles. This would explain how he managed to avoid the numerous warriors now commanding the compound.”

Many of the cabins were actually part of the stockade wall. If Randolph’s cabin was one of these, then jumping off the cabin landed him in the woods beyond the wall. This would explain his fortunate escape amid the havoc. His other small child suffered the fate of Randolph’s wife. The text, Collins History, portrays Randolph as fighting two more Indians after he dropped off the roof and broke free to safety. Again, a heroic effort to save one’s family or the remnants of it.

William Harrison realized the chances for his wife and a second elderly female to escape were slim. Their cabin had a dug-out, a hole beneath the floor for storage. He pulled back a floor board, hid the ladies in this space, replaced the wide floor board that covered them and made his way out through the roof. This was not unusual. Frontier cabins often had a built in escape hatch. One account indicates the Harrison cabin was located in the center of the compound, making his escape all the more difficult. The same source relates how the two ladies rolled out a keg of spirits they found in the basement. This keg distracted the Indians and the ladies remained safe in their hiding place. Again, one has to wonder at the embellishments that get added to these stories over the years.

Harrison somehow got out of the station safely and the ladies momentarily survived under the cabin floor which was being burned above their heads. When the cabin began collapsing they decided to wait no longer. They were facing a certain and painful death if they remained in the developing inferno. They crept out, almost nude, to discover the cabin and the station a burning ruin. The war party had killed, plundered and destroyed the pioneer outpost in a matter of minutes. The Indians had rounded up their prisoners, completed all necessary looting and headed north to the Ohio River. It would take some time for the pioneers to organize their chase, if there was to be a chase at all.

Let’s take a quick look at the damage wrought by this massacre. Of the ten members of our Davis family, father Cornelius was dead. Mrs. Davis was the only one of the ten members of her family to escape. She fled the scene with Mrs. Ash and Benjamin Ash. Mrs. Davis’ seven year old son Isaac Davis was taken captive. The remaining seven of her children were killed. Osborne Bland was taken prisoner and his wife escaped. A very pregnant Mrs. Polk (wife of Captain Polk) was taken prisoner along with her four children (ages 2 thru 7) and forced marched to Detroit. Other records indicate two of her children died when their cabin was burned down around them. Prisoners were taken to Detroit, where they were sold either as slaves or set free by the person purchasing them. It was in Detroit that Captain Polk had the good fortune to find his wife. Bland returned from bondage after three years and reunited with his wife in Nelson County. They raised sheep for sustenance.

The Burnt Station was never rebuilt. A year after the massacre a visitor noted only a few huts marking the site.

Battle of the Blue Licks

At the Battle of the Blue Licks, when the pursuing settlers overtook the Indians at Licking Run, Boone, Todd, and Harrod all urged that they should await the arrival of General Logan who was gathering the riflemen around Danville and Stanford. Logan would arrive within twenty-four hours with those reinforcements. But the hot-heads and the reckless soldiers urged immediate battle, led by Major McGary, who rushed into the stream exclaiming, “All who are not cowards will follow me.” All followed and paid a fearful penalty for their rashness. It was 100 years before the nation would wonder at the idiotic decision making of Colonel Custer at the Little Big Horn. McGrary wrote the book on suicidal tendencies of western officers. Custer forgot to read it.

As Boone had predicted, General Logan arrived the next morning. They buried the dead as quietly as possible, and followed the Indians to the Ohio River. Logan believed they had all left Kentucky, but he was mistaken.

“With the devilish cunning peculiar to the North American Indian, a band said to have numbered seventeen, slipped away from the main body leaving no trace of their movements. They passed silently between the settlements and into Nelson County. They camped at Dugans Spring, some two miles east of Polk’s Station.”

And we know what happened at Dugan’s Spring.

The massacres did not end at Kincheloe. In 1781 or 1782 a small band of Indians attacked Rogers Station and were met with stern resistance. It has been estimated that more than 1500 people were killed by Tribes seeking to take back their lands. 20,000 houses were burned to the ground. The Rogers Family is found marrying into the Stilley and Davis line of our Smith family.

This would not be the last tragic massacre a Davis Family would face, as we shall see in the Black Hawk War of 1832. From the very first moments that Davis family members stepped on New World ground in Maine and Jamestown, they seemed destined to push inland and up against the Native communities. And those communities, tribes, nations…. would not back down when faced with destruction.

Harrowing accounts of events at Kincheloe Station can be found in:

History of Kentucky by Z. F. Smith

“The Saturday Gazette” published in Bardstown, October 1, 1841, contained an article entitled “Memoirs of the Burnt Station.”Authored by Major Thomas Speed, the article is a ghastly recital of Indian warfare. The article speaks of the “dark and bloody ground.”

Afterwords

My father regaled me with his stories about the Davis and Stilley children being taken captive, after parents were left for dead. Historical records verify that my father had some insight but not the detail that can be found today. He was never sure where the stories originated, where events took place and who in particular was involved. He was certain though that ancestors had been kidnapped in Native raids on our families.

In the case of Kincheloe Station:

The young son, Isaac Davis, age seven was captured and taken to Detroit Michigan. As Z.F. Smith relates the details:

There, Isaac was adopted by an Indian Squaw, who treated him with maternal regard, even decorating him with rings in the nose. On one occasion when threatened with invasion by the whites, she secreted him in the top of a fallen tree some distance from their village, till the impending danger had passed. After his return to Kentucky and the area of Nelson County, Isaac still had signs of the nose decorations and at times wore these ornaments as well as rings in his ears. He also spoke in high terms of the kindness of the Indians toward himself and other prisoners. He seemed to regard them as his benefactor, not withstanding the barbarities perpetrated on his family at the taking of the Fort. Even so he recalled vividly and never forgot that apparition of his father, “entering the cabin covered with blood from his wounds, his shirt, the only clothing he had on, in a light blaze, his countenance pale and haggard”.

The Blue Licks Battle Field is found on a horse shoe bend in the Licking Creek. Many of our ancestors resided in the immediate vicinity of the battle field. I will identify those families when I get a chance.

Early accounts of Blue Licks describe it as a place where animals gathered to lick the salt deposits flowing from the springs in the area. The Reverend James Smith provides this account in his 1795-97 diary:

“As you approach the Licks, at the distance of 4 or 5 miles from it, you begin to perceive the change. The earth seems to be worn away; the roots of the trees lie naked and bare; the rocks forsaken of the earth, that once covered them, lie naked on the neighboring hills, and roads of an amazing size, in all directions, unite at the Licks, as their common center. Here immense herds of buffalo used formerly to meet and with their fighting, scraping etc., have worn away the ground to what it is at present.”

Online related articles from which I generously stole:

Bloomfield Newspaper Historical Edition Covering “Burnt Station” events

Thomas Watson Research (2010) Related to “Burnt Station”