The Settlement of Doeg’s Neck (Mason Neck)

In previous discussions I have provided examples of the verbiage produced by those madcap guys in the Virginia Colony deed office. Frustrated screenwriters whose talents failed Shakespeare’s talent contests, the authors of Virginia deeds were often accused of creating descriptions of property lines that were foreign to even the finest minds of the colony. It was suspected at one time that they were nom de plume authors of the earliest versions of the Onion Newspaper. Witness the eloquent put down provided by George Mason IV in his complaint to William Fitzhugh in the winter of 1787:

“You will find some Circumstances in this Affair too difficult and mysterious to be unravelled, or accounted for, without better Lights or Evidence, than it is possible, at this time of Day, to procure; they can therefore only be guessed at” [1]

At first I thought I was reading Mason’s take on a tawdry Ben Franklin romance that had been uncovered in the dark of night. But no. Mason was describing the verbiage of patents and land boundaries in 1787. The colonial land records were a source of frustration for several generations of historians, genealogists, Lawyers Without Borders, Families after Funerals and the FFLS (Federally Funded Land Speculators). My hats off to the folks, over the centuries, who have been charged with maintaining these records. The records are relatively complete despite the impact of Revolutionary and Civil Wars; and well preserved despite the occasional courthouse fire or marauding band of hungry soldiers. But descriptions of the land found in deeds are a bit like the lingerie found in a Victoria Secrets catalog: exceedingly brief, highly generalized and specific only in the acreage conveyed. Here are just a few of the entertaining jaunts through the Virginia wilderness provided by the finest of Virginia’s land office agents in 1650:

“Peeter Smith, 500 acs. in Petomeck freshes, N.Ely, upon a creek above Col. Speakes land.”

“Stephen Robinson, 500 acs. bounding N.Ely, upon a br. of Potomack freshes nere the head of a great Cr.”

“at Frederick Fartsons cor. at the extent of his EN.E. line, running along same &c. upon said Riv. beg.at Mr. Fosons cor tree standing nere a br. of Hartquack Cr.” [2]

Okay. Stop me here before I get carried away, but that name ‘Fartsons’ had to be an early example of trolling the public. These examples illlustrate why guys like George Washington and our own William Bailey Smith made a nice living, surveying land and insuring property lines. You see the difficulties: Potomac is spelled in a variety of ways, none matching the present day accepted spelling and none matching the original phonetic spelling as interpreted by white guys listening to the Doeg Natives talking. Abbreviations are strewn all over the place like rocks in glacial fields. And what happens years after this deed is published, if ‘Col. Speake’ has up and died, and folks forget where he lived in the ‘Potomack freshes’? I can hear the attorneys now, parading witnesses through the courtroom, each with a different memory of the Colonel’s property line.

And what in the name of St. Peter are ‘freshes’? I didn’t know. I had to Google it and got an education. I can now point to the marsh that, 400 years later, still sits to the east of Peeter’s original purchase. Today the marsh (freshes) is a wildlife preserve. Peeter’s property now plays host to an 18 hole golf course and the Pirate’s Cove Water Slide Park. I am sure this is what Peeter had in mind when he envisioned the future of his original purchase.

I had no idea where Peeter’s 500 acres were located until recently. I had been digging for quite awhile, identifying the names of investors, locating similar deeds and searching for a place in Virginia where Peeter’s property could be found. I knew he held title to lands in Westmoreland and Prince William but this spot of land remained a mystery. It is a bit removed from the Westmoreland shoreland that, in 1650, was first subject to settlement. In fact, by early Virginia standards, the land is a lot removed from ‘civilization’ as defined by guys in white wigs and pointy toed ballet slippers on Fleet Street.

I started with a single, brief entry in Nugents, Cavaliers and Pioneers, Virginia Abstracts from 1623-1800. [3] I Googled keywords over the course of months until one day I stumbled across the Gunston Hall website, and a nice narrative written by Robert Morgan Moxham. And there, before my eyes and under my nose, I found the plat map showing Peeter Smith’s purchase, and that of his friends. Voila! I can now walk out on the 15th Fairway of the Pohick Bay Golf Course and hit a nine iron into a water feature that was probably a watering hole for Peeter’s first few head of cattle.

I have not been able to determine if Peeter actually held on to this land for very long or not. Was it his homestead or a prime investment property for which he held title? The inadequate patent descriptions that (140 years later) led George Mason IV to complain (and my eyes to go prolapse) led to a century of legal conflicts among neighbors, friends and family. The records and surveys that resulted from courtroom battles have been partially preserved and allow a patient plotter to construct the colonial land boundaries with a fair degree of confidence. In other words, when the original deeds failed as landmark trees died and brooks disappeared or altered course, the courts intervened and determined where the lines should be drawn. Colonial land law required that a guy like Peeter (a patentee) plant the land (the dividend) in crops and make improvements within three years. If the patentee failed to plant a crop or make improvements the land was ‘deemed escheated’ and available to the next claimant. There were many abandoned lands. It looked like Detroit for awhile without the smokestacks.

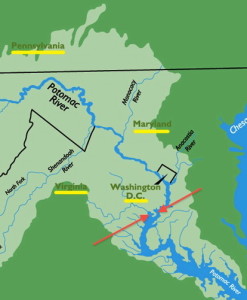

When Peeter bought these 500 acres in the ‘Petomeck freshes’ (marshland) he had no idea he was sitting on land that would be consumed by the urban sprawl of Washington D.C. The United States were 150 years down the road. The namesake of the future capital, George Washington was a century away from his grand entry on earth. Washington’s DNA was coarsing through the life stream of great grandparents who were already lodged in the neighborhood, mixing it up with the Smiths, Bonums, Philpotts, Walkers and Lees. [4] Peeter’s land holding on Doeg’s Head was the future homestead of George Mason IV. Peeter’s initial investment here on the Neck would eventually be bought and sold and eventually acquired by George Mason I on his way to creating an elaborate plantation system. Who was George Mason IV? Let’s go to Wikipedia and allow me to steal a quick bio. When I taught history, George Mason was one of my favorite Revolutionary War heroes.

“George Mason (sometimes referred to as George Mason IV) (December 11, 1725 – October 7, 1792) was a Virginia planter, politician, and a delegate to the U.S. Constitutional Convention of 1787, one of three men who refused to sign. His writings, including substantial portions of the Fairfax Resolves of 1774, the Virginia Declaration of Rights of 1776, and his Objections to this Constitution of Government (1787) in opposition to ratification of the constitution, have been a significant influence on political thought and events. The Virginia Declaration of Rights served as a basis for the United States Bill of Rights, of which he has been deemed the father. [5]

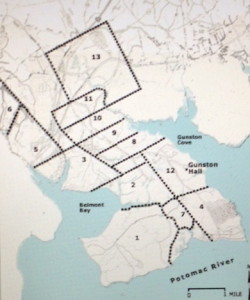

It was George Mason and several other guys who pushed the Bill of Rights into place. He was a neighbor to Peeter’s Descendants, a family attorney and a judicator in a court case that pitted brother against brother in a Smith property dispute. This Doeg property purchased by Peeter is identified in Table I as #10. His 500 acres rests at that point where the Pohick Creek joins Gunston Cove on the Potomac River. The family plantation(s) of the George Masons (I thru VI) occupied this peninsula for more than a century. The name Doegs Neck gave way to Mason Neck, a promontory bounded on three sides by the Occoquan and Potomac Rivers and Pohick Creek. Moxham reports that

“Mason Neck was patented by adventurers who travelled up the Occoquan River and Pohick Creek which gave access to the land between. The dimensions of the Neck are such that it could accommodate one tier of moderately-sized claims parallel to each waterway, with the tracts having a common boundary along the median of the Neck.” [6]

In Table I Moxham provides the plat map I have been looking for. The original land patents on Doegs (Mason) Neck, 1651-1666

- Robert Turney 1651 2109 acres

- John Jenkin, 1653 1000 acres

- Gervais Dodson 1653 1300 acres

- Thomas Speake 1653 1000 acres

- Richard Boren 1654 650 acres

- Miles Cary 1654 3000 acres

- John Mottrom 1654 360 acres

- John Gosnell 1657 500 acres

- Wm. Newberry 1654 500 acres

- Peeter Smith 1657 500 acres

- Thomas Molten 1657 500 acres

- Richard Bushrod 1660 2000 acres

- Normansell & Scarlett 1666 2550 acres

Patentees may be identified by the numbers keyed to Table 1. [7] Moxham assures the reader that the original boundaries were eventually surveyed and their correct position established for posterity. The location of each patent with respect to adjoining patents is thought to be correct, but he does advise that “boundaries are highly speculative, in several instances.” The first patent north of the Occoquan River was given July 8th, in 1651 to Robert Turney (1), for 2109 acres at the junction of the Occoquan and Potomac Rivers.[8] He referred to the tract as “Doggs Island.”[9] That name is more frequently spelled ‘Doegs’ and appears often in descriptions of lands deeded along the Occoquan and Rappahannock Rivers.

The Doegs were a Native American nation that had flourished in the area prior to the devastation brought on by European disease. The island and neck were also called Miomspses (AKA: Myampses or Moyumpse). As if to illustrate the point that incompetence reigned supreme in the Virginia Land office the distribution of lands along the Occuquan River created more confusion. There were at least two interfering sets of patents for the entire area, and four patents for the same land were given over a period of about 20 years.[11] Our Smiths (if our premise holds true) are found in the company of Colonel Thomas Speakes on both Doegs Neck and on a separate property to the south, on Nominy Bay, Westmoreland County. The first land deeded on the Pohick Creek side of the Doegs Neck, 1000 acres at the mouth of that stream, was entered by Col. Thomas Speake in September, 1653.[12] Moxham notes that

“four years passed before Pohick Creek again attracted land-seekers, at which time four adventurers took up a tier of claims above (upstream from) Col. Speake. They evidently left about 1000 acres between themselves and Speake, which was later taken by Richard Bushrod in 1660.”[13]

Peeter Smith was one of the “four adventurers” who “took up a tier of claims above Col. Speake.” The ‘four’ included Gosnell, Newberry and Molten, along with Peeter. This is how we begin identifying neighborhoods and business partners. People tended to band together and move together back in the day. Again, the variations on the spelling of names becomes a factor. Was Gosnell originally Gosnold? Were Molten, Moulten and Mottrom one in the same? Can it be assumed that Peeter was a correct spelling distinguished from Peter? Will any of these names be relevant in this quest?

Moxham believes many of the original Doegs Neck patents (shown in Figure 1) were purchased by speculators, sold several times, abandoned and reissued to later claimants. It is not uncommon to find the word ‘escheated’ in the brief descriptions of deeds. Moxham’s point regarding frequent exchanges is illustrated by the following description of a Doegs Neck property adjacent to Peter Smith.

Stephen Robinson, 500 acres… beyond Col. Speakes land…upon Peter Smiths …. granted to Thomas Moulton… assigned to John Wood… who assigned to William Thomas…. by him assigned to William Betts, who gave and assigned to said Robinson…. Oct. 1665.

This property went through 6 hands in a matter of 8 years if one counts the original patentee who sold to Moulton. This rapid movement of land from hand to hand makes it difficult, in some ways, to trace family history and identify homesteads. You might ask, “Why is it important to identify a homestead from four hundred years ago?” Some of us get goosebumps standing on ground that was worked by our ancestors and others amongst us could, frankly, give a rat’s ass. I get goose bumps, literally.

Cat Stevens put the words into song a half century ago: “We are only dancing on this Earth for a short time.” It will be a profound moment when I stand where my forefathers stood and stare at the night sky in wonder at the steps they took in this journey of life. What makes this particular find on Doegs Neck all the more remarkable is that Stephen Robinson‘s DNA passed through the centuries to my Aunt Margaret “Robbie” Robinson, the wife of my uncle William “Bill” Smith, descendant of Peeter Smith. Small world?

Concern about accuracy with regards to boundaries increased when a family purchased land with the intent of settling in and making the property their homestead. A farmer would make sure that corner trees were blazed in, lines surveyed from one tree to the next and marked along the way. They knew the acreage to which they were entitled and laid out lines that would secure the best land, water features and access. The first to ‘settle in’ often gained an advantage over the next to arrive by simply marking the best turf available. Thus, contributing to the confusion in the Land Office and courts. To locate Doegs Neck and Peeter Smith’s 500 acres go to Google Earth and plug in the coordinates: 38 degrees and 41’ North Latititude and 77 degrees and 12’ West Longitude. Or for simplicity’s sake just stare at the map below for a few minutes and picture a plate of Chesapeake Bay Blue Crab..

Now that we have pinned down one of Peeter Smith’s investments let’s look at the guys he was hanging with in 1657. Their names are lined up on Doegs Neck plat map above. I have to be honest. I am an old history teacher and I didn’t know squat about any of these guys. Universities don’t press the names of these guys into the forefront of the mind of students taking the Survey of American History class. The events they participated in escape the attention of a lot of scholars. And again, we aren’t assuming they built manor homes on their lots or developed condos, beachfront gazebos or attended lawn parties at the country club. However, the population was still miniscule and these guys may have been drawn into events that allow us to develop a better sense fir who they were as human beings making a go of it as pioneers in someone else’s garden

Let’s start with John Mottrom in Lot 7. Mottrom was probably the first Englishman to settle on the Northumberland/Westmoreland side of the Potomac River, and his home was a refuge for Protestants fleeing Lord Calvert’s Catholic Maryland.[11] His home, Coan Hall, served as the first county seat of Northumberland county. He presided over the county court for more than four years until his death in 1655. He was the first burgess serving Northumberland County in the Virginia House of Burgesses. As Northumberland grew in population, Westmoreland was hatched to the north and west end of the Great Neck.

Doegs Head was a late addition to Mottrom’s property portfolio. He also owned property along or near the Great Wicomico River and the Chickacoan River. He owned land on or close to Hull, King’s, and Chickacoan creeks. Like alot of the plantation owners up and down the river and bay, Mottrom was a multifaceted planter and merchant owning his own shallop. From his position on the Potomoc he established a profitable trade with Maryland. [12] He was an old fellow in the Nominy Bay neighborhood and a bit of a rebel to boot. That boat out there on the end of his pier was used for more than just trade. During the final decade of his life (d.1655) Mottrom was engaged in one war against Natives on the frontier of the growing Virginia colony and one rebellion against Governor Calvert of Maryland which has been recorded in history as Ingle’s Rebellion.

A merchant from York County, Virginia, Mottrom settled on the Chicacoan River and established an early trading post. An Indian attack occurred on Holy Thursday, 18 April 1644, which killed roughly 500 settlers, a larger slaughter than occurred in Jamestown in 1622. A war ensued, which usually happens when you massacre 500 folks. To put things in perspective, Maryland had about 600 settlers in 1644. The war with the Natives lasted for two years off and on, here and there.

As part of a peace treaty signed in October 1646, the Virginians again promised not to settle on the Middle Peninsula and Northern Neck. The British and the Colony of Virginia decided that any white guy living on the far shore of the Rhappahonnock River was crazy and deserved to die. They promised the Native population that they, the Brits, would leave that parcel of property alone. “Right,” the Natives muttered, “We’ve heard that before!” Consequently, the earliest white settlers at Chicacoan, including Mottrom, were there on their own, independent of any Virginia government protection. There were no taxes, no Justices or Sheriff – no official authority of any kind. This is where the NRA mantra,”My Gun is the Law” got started. It was a great place for Ayn Rand, Rand Paul and their Libertarian followers.

Within two years the Colony of Virginia abrogated the 1646 treaty with the Chickacone Indians and annexed the entire Northern Neck establishing the County of Northumberland in January, 1648. While keeping one eye on his Virginia assets, Mottrom maintained an equal focus on his business operations in Maryland, just across the Potomoc River in St. Marys. Life was in a state of chaos in Maryland as well. Mottrom and his protestant business partners were concerned about the predilections of Lord Calvert, the Roman Catholic CEO of Maryland.

John Mottrom is actually found in our family tree as one of several husbands of my ninth great grandmother, a character by the name of Ursula Bysshe. Ursula had a habit of picking men who had about five years left in the tank. Richard Thompson (d.1649), John Mottrom (d. 1655), and Major George Colcough (d. 1663) all supported the woman in the manner she preferred. Richard Thompson is our ninth great grandfather. The other two guys, including Mottrom, would be step great grandfathers I suppose.

Mottrom was first married to a Mary Spencer and had at least three children by her: Ann (1639-1707), John Jr. (1642-?) and Frances (1645–1720). The Spencers also bump into our Smiths along the way. They had to, it wasn’t like the peninsula was overrun with people. I would like to come back to this extended family a little later to show you just how inter-married a British family lodged into a small peninsula can become. It’s an amazing and veritable Gordian Knot.

Colonel Thomas Speake, Lot 4

The Colonel was born in Hazelbury, Wiltshire, England in 1622 and arrived in Virginia in 1639. The Speakes family of Wiltshire was wealthy. A descendant in Speake’s family, Ann, married Lord North, the Prime Minister of England who earned the scorn of the colonies heading into the Revolutionary War. Colonel Speakes had been dead and buried for a good century before Ann’s wedding to North, so he (the Colonel) never got the invite! Speakes was a devout Catholic and first settled in Lord Calvert’s refuge for Catholics in Maryland. The Ingles Rebellion of 1644/45 may have driven him over the edge as he soon moved across the Potomac, into Westmoreland County where he began acquiring land faster than a buck in rut. Speakes was also a Royalist, whose support for the monarch was unflinching. This made him an oddity as Catholic Royalists were considered walking contradictions, oxymorons.

In 1642, Speakes and William Hardidge were 2 of 13 soldiers responsible for clearing Natives from Kent Island in the Potomoc River. You might think it odd that only 13 guys were needed to clear a tribe from an island. Keep in mind Smallpox had reduced tribal populations by as much as 99 percent, leaving remnants of once festive and flourishing villages to die in squalor. Clearing the island was more like clearing the homeless off the streets of a Jersey city. Hardidge was also one of Mottrom’s accomplices in the Ingles Rebellion. Speakes was not. The two became neighbors on Nomini Bay. Hardidge’s son Richard would become the widow Speakes’ fifth and final husband. She had a propensity for robbing the cradle if it possessed wealth. John Rosier and Lewis Burwell owned plantations adjacent to the Colonel in Nomini Bay. Another Ingles accomplice, William Baldridge, joined Speakes on Nominy Bay.

Speakes acquired two tracts of land, each in prime locations: The 600 acre Currioman plantation on the bay of the same name and the 400 acre Nomini Hall on Nomini Bay. Our Peter Smith Sr. lived near Speakes on Nomini Bay and owned land near Speakes at Doegs Head. Neither man appears to have developed Doegs Head deeds and Speakes appears to have allowed his to be declared escheat in 1657. Both men were sons of the Wiltshire region in England. I don’t know if that means anything at all.

Richard Bushrod, Lot 12

Richard was the second son of Richard Bushrod, English merchant and explorer. Richard’s son John bought up land on Nomini Bay that became Bushfield Plantation. John Bushrod I willed the Bushfield Plantation to his son, John Bushrod II. John Bushrod II had two daughters, Hannah & Elizabeth. Hannah became his heir and inherited the Bushfield Plantation. By the time her father had died, Hannah had married John Augustine Washington (I), the brother of President George Washington.

Myles Cary, Lot 6

Cary (b.1623) in Bristol, England, was the son of a woolen draper, John Cary. The English Civil Wars divided the family, and Cary’s father suffered substantial losses in the woolen industry. As an end result, Cary became involved in the tobacco trade and moved to Virginia in the 1640s. His name first surfaces in America in a 1645 deposition citing him for shorting a guy 250 pounds of tobacco. Remember: Tobacco was king. Tobacco was currency in the colony. Cary initially resided in the Warwick County household of Thomas Taylor, who may have been a kinsman, and by about 1646 he had married Taylor’s daughter Anne. Several points common to Peter Smith’s family line appear here: the Wool industry background that Myles and Peter may share, an English Civil War that sent them off in the direction of Westmoreland. And there is the tie into the Taylor family, one hundred years prior to James Smith’s marriage to Elizabeth Taylor. The point being that it was a small population in Westmoreland and one big happy family.