JAMES SMITH 1708-1749 (ggf5) and ELIZABETH PRESLY TAYLOR 1700-1771 (ggm5)

Mount Airy, pictured above, is the home of the Taylor (Tayloe) family, from which our great grandmother (ggm5) Elizabeth Taylor was born. The plantation home pictured here was constructed by her brother, Colonel John Tayloe II in 1764 near the village of Warsaw VA. Elizabeth was already a widow in 1764 and remarried. Her years as a Smith were behind her. The plantation was an equestrian center and designed specifically to breed and develop the finest race track horses of the 18th century. The Tayloe family, along with the Carters, were the wealthiest of the wealthy in the British colony. They owned a number of plantations, iron works and mines. They were entrepreneurs, venture capitalists and plantation executives. That a Smith would marry into the wealthy family was not a stretch. They shared the same neighborhood, churches and social events.

John Taylor, a predecessor of John Taylor I and II married an Anne Smith in the 1680’s and Anne Smith may have been a sister of Peter of Yeocomico. More evidence and documentation is needed to establish a deeper root in the family tree prior to Peter Smith of Yeocomico. The Taylor line is well documented and John Taylor’s will in 1748 clearly cites Elizabeth Smith as his daughter, as well as a daughter Hannah and two sons: Henry and John. Records also indicate that our Elizabeth also had the name ‘Presly’ as a part of her maiden name. Elizabeth’s mother was Elizabeth Presly (Presley), daughter of Peter Presly and Elizabeth Thompson. The Presley, Thompson and Taylor families are full of crazy stories and accomplishments, some good and some not so much! Descendants of these families will filter across the continent together.

Finding Elizabeth Presly Taylor and accurately tracking down her roots took an inordinate amount of time. Her name plagued me for several years. Was she by birth a Presly and a widow of a Taylor? Or vice versa? Was she a widow of a Presly and Taylor and her maiden name lost? These are common issues that arise in this dung hill of genealogical history. Add to those mysteries the number of family trees that blindly root themselves into the Taylor family, hoping to own a bathroom at Mount Airy. None of the trees I examined provided evidence linking Elizabeth to any connubial bliss in the Taylor bedrooms nine months prior to her arrival on Earth.

And then I one those ‘Oh Yes! I hit the jackpot!’ moments when I found the will of John Taylor (1748) while looking through Fairfax County files for property deeds. I busted out in a disco dance and a move that nearly discombobulated the new titanium pipe that is my right hip.

One can miss a number of interesting characters if we look only for great grandfathers and ignore the grandmothers, aunts, uncles and cousins. It is narrow minded to look only for our surname (the male descendants) in history. We are a compilation of a lot of cool DNA! We miss a lot of details that make for entertaining campfire stories if we narrow our focus too much. Imagine the permutations if these ten sets of parents (the children of Peter of Yeocomico) each had ten children. Voila! 100 kids! Christmas would never be the same for old Peter had he lived to see that day.

Imagine also the number of famous names found in these various colonial families and the stories that become the cloth from which a nation’s history was fabricated. But consider this: Our history books reflect on but a few of our nation’s icons. Found beyond the few great names like Washington and Jefferson are a number of folks who drew less attention and accomplished a great deal. We are part of that story. We are both the flower and the seed of those who planted the earth before us and paved the path we trod, allowing us to not only live, but flourish, should we so choose. But what rights and responsibilities come with this inheritance?

To keep things somewhat focused: We will move from Peter Smith of Yeocomico (1663-1741) in Westmoreland County, Virginia to his son: James Smith (1708-1749) who moved to Fairfax County. I will then introduce the son of James: Peter Smith of Round Hill (1734-1797) who moved from Bull Run, Fairfax County to Caswell County, North Carolina. We will cover three generations (1663 thru 1797).

After a little detective work, I will then introduce you to some of the characters and stories that litter the landscape from Chesapeake Bay to the Mississippi River Valley. Pay attention: Daniel Boone is one name that will crop up. George Mason is another. And how about Supreme Court Chief Justice, John Marshall? That ought to whet your appetite. Again, I don’t make these stories up. They are recorded in history. I will link you to the sources so you can check my credibility. I am part Irish after all and need my mother’s German roots to keep the Irishman in check. I fight with myself. A lot.

To see where James Smith and Elizabeth fit into our tree please click on this link Westmoreland Smiths

The Civil War disrupted every aspect of the American life, both north and south of the Mason Dixon line. Many of the early records of Fairfax County, from the 1700’s, were destroyed during the Civil War (1860’s). Soldiers occupied the Fairfax County Court House and used the documents to start fires on cold winter nights. Among the records that survived are the wills of three sons of Peter of Yeocomico: William, Thomas, and James Smith. Somehow we lucked out and their wills contribute to a wider and more detailed picture of Smiths in our family tree.

From the Reverend Slaughter’s History of Truro Parish we learn that among the “Voters at an election of Burgesses in Fairfax County in 1744″ were my great (5x) grandfather James Smith and two of his brothers: Thomas Smith and William Smith. Each was a recipient of 325 acres in Truro Parish by way of their father’s will in 1741. These allotments of 325 acres were part of the Bull Run estate Peter of Yeocomico purchased in 1715.

James was born in Westmoreland County in 1708, about the time of his Uncle Jame’s death. We met Uncle Jim and his daughter Hannah Breel briefly when we examined his will. Our ‘Grampa’ James and wife ‘Granny’ Elizabeth started raising a family in 1732 when their daughter Elizabeth was born. She was followed by Peter (of Round Hill) (1734-1791), William Bailey Smith (1737-), John (1738-1822), Presley (1740-1819) and Nancy Ann (1744-1819). Notice the son’s name, ‘Presley.’ It was common to honor the mother’s family by using a family surname as a first or middle name for a child. Thus, Presley Smith was named after grandmother Elizabeth Presly. This was also often a matter of branding, so to speak. The ‘Presley’ name was a big name in Virginia. The Colonel was a prestigious individual and a man of great wealth. His prestigiousness becomes evident when researching the birth certificates in Virginia in the 1700’s. A whole lot of guys had the first name, Presley, inked on the old birth certificate. And yes, I know ‘prestigiousness’ is not a word.

The will of our grandfather (ggf5), James, is dated October 14, 1749 and was probated on September 24, 1751. It is a lengthy document and posted in this blog compliments of Pearl O. Smith (1973). Pearl Smith did one heck of a lot of research, upon which descendants have banked numerous efforts. Her work is immaculate, honest and well documented. Please help yourself to her website and enjoy the details she provides on numerous relatives. James designated his “loving wife Elizabeth” as “my executor.” Interestingly enough, one of the witnesses to the will was Hugh Thomas (James Smith’s brother in law). The Thomas boys invested in land to the north of the Smith estate at Bull Run. Please see the plat map of the Clifton patent. The inventory attached to the will of James indicates that he owned stuff not found in the home of the average citizen at that time: valances, curtains and books, as examples. This indicates that he was a man of wealth, more so than not.

I can’t help but read his will and think of those folks who were identified as slaves: ‘one Negro woman named Janey,’ ‘one Negro woman named Sue,’ ‘one Negro girl named Beck.’ Each of these women is given “to him and the heirs of his body” and “with all increase.” This is the language that locks a slave into the custody of the master and that master’s children. It also locks into the master’s custody any ‘increase’, that is: any child born to the slave. So human beings transferred from one household to the next along with the curtains, valances and library books. The one line in the will that really got me however was the mention of Anne’s entitlement in her father’s will:

“I give to my daughter Anne Smith the sum of 25 pounds current money or a young Negro at the discretion of my executors.”

That is correct. Anne could have 25 pounds (Virginia was still a British colony) or “a young Negro.” Her choice. Unfortunately, Our nation had to endure another 115 years of slavery before the Emancipation Proclamation launched a new era in American history and created new challenges in race relationships.

Elizabeth Smith, James’ widow, did rebound from the death of James and married a James Landman some time prior to 1767. Evidence of that second marriage is found when the son of James and Elizabeth Smith, our Peter of Round Hill (ggf4), sold land in North Carolina to James Lamman (aka Landman) in 1789. We know that this Peter, son of James, moved to Caswell County, North Carolina. It is highly probable that his mother Elizabeth and Mr. Lamman (Landman) joined him for a spell. Elizabeth’s sons William Bailey Smith and Presley Smith also lived in North Carolina, albeit briefly, and then headed north into Kentucky. We will cover these illustrious souls a bit later. Kentucky proves to be an interesting stop for the Smith family migration from the Atlantic Coast to the Great Plains. Daughter Nancy Anne Smith Boggess eventually moved to Kentucky with her husband Richard Boggess. How many of their ten children went with them I do not know. Mother Elizabeth Smith Lamman had no children left in Virginia. It is not known when or where she died.

I find it very interesting that a person like Elizabeth Presly Taylor Smith could be born into the great Taylor family wealth, marry into a prosperous Smith family and then die unknown, perhaps in the Kentucky wilderness. It was not unusual however. The land beyond the Blue Ridge was a great wilderness forest. It sucked up alot of lives, just as the Atlantic Ocean had done with many dreamers. It required a hearty soul to survive and skills not taught by east coast tutors.

It is important to understand just how vast the Tayloe wealth became and how insidious. The Tayloes managed a corporate empire with large scale operations in Virginia and Alabama. The Tayloes moved many of their slaves from Richmond County, Virginia to the Black Belt of Alabama between 1830 and 1860. There were Tayloe slaves in King George and Prince William counties in Virginia and Marengo County, Alabama. They had such a massive operation that they were forced to keep very good records. Fortunately for us, many of their records did survive and are housed at the Virginia Historical Society. There are around 100 microfilm rolls recording the names of human beings enslaved on Tayloe plantations and 27,500 documents related to corporate and personal affairs on file.

The Tayloes used slaves on their 35,000 acres of tobacco plantations in Virginia, and in their Neabsco iron works. The records use “surnames” for the slaves well before the end of slavery. This system allowed the master to distinguish their many slaves and track their genetic make up for breeding purposes. The Mount Airy ‘farm’, as present owners refer to it, was a breeding ground for the finest horses. But the Tayloes were also well versed in the breeding of slaves for the lucrative slave market.

As the soil deteriorated in Virginia from overuse and the profitability of cotton increased, the Tayloes expanded their operations into the deep south cotton belt. With the Civil War looming large, the Tayloes moved many of their slaves into Alabama.

One author writes:

“My ggg grandfather John Collins was in charge of bringing many of the Tayloe slaves from Virginia to Alabama. Because of his association with the Tayloes, he became a very wealthy man. Although he was never married he did have many children through at least two slave “wives”. Many of the mulatto Collins from Hale county claim John Collins as their ancestor.”

This author provided assistance to a young lady seeking to trace the history of enslaved ancestors:

“My name is Johanna Eatmon. My Eatmon family traces back to Warsaw, VA and Mount Airy. My husband’s great grandfather, Louis, was a slave there. My husband’s grandparents were sharecroppers at Brown’s Station, Alabama. I believe the Browns had business relationships with the Tayloes. At the onset of the Civil War part of the family was moved to the Black Belt region of Alabama. Along with other slave families- Wormley, Richardson, Ward and the Moores. My husband was born in Alabama and knows all of these families listed above. They still live in close proximity to one another. The GGGrandson of the overseer (Collins) who was hired to move the families south gave me these names.”

The number of slaves the Tayloes marched to Alabama was not a mere bus load. In a running thread regarding Mt. Airy, the Tayloes and slavery Tom Blake (3/8/2002) notes:

“Through my Large Slaveholder home page link below, you can find information on 3 Tayloe plantations in Marengo Co. AL, each holding 115, 125 and 150 slaves respectively. E.T. Tayloe held an additional 104 slaves hostage at Woodville in Perry Co. AL (See page 474 of the 1860 slave census).”

Tayloes were not the only plantation overlords moving their stock into the deep south. The family surnames mentioned in Johanna Eatmon’s passage are the family names of the Westmoreland neighbors, friends and relations of our Peter Smith, a full 200 years prior to the Civil War. The Wormeleys, Moores, Wards and the Browns of Brown Station and many others attended church with our folks, served as pall bearers, officials for deeds, marriage licenses and wills. Like the slave families identified by Ms. Eatmon, our families also tended to ban together and travel in packs.

Interesting patterns emerged as these migrations moved like Caribou across the face of the earth, from Atlantic coastal plains to the Great Plains. Surnames found in Westmoreland and Accomack in the 1600’s are bound together in wagon trains that follow newly established trails to places like Spartanburg (South Carolina), Caswell County (North Carolina), Muhlenburg (Kentucky) and Posey County (Indiana).

PETER SMITH OF ROUND HILL (1734-1797) (ggf4) and JEMIMA SIMPSON (1743-1793) (ggm4)

Peter Smith, son of James and Elizabeth Smith and grandson of Peter Smith of Yeocomico (Westmoreland County, VA) was often referred to as “Peter Smith of Caswell County.” He was also referred to as “Round Hill Peter Smith” in the census reports, to distinguish him from other Peter Smiths who happened along. He was born in Prince William County, Virginia, about 1734 and may have been the oldest of James Smith’s sons. He married Jemima Simpson, of Fairfax County. A part of Prince William County had been incorporated into Fairfax County.

Jemima’s father was George Simpson. [1] In his will George named several children and added that his daughters who had already married and left home had received their share.[2] This was customary. A dowery of property usually accompanied a young lady as she was betrothed. George Simpson identified two sons, Aaron and Richard, in his will. Men by these names resided in Caswell County, down the road from Jemima Simpson Smith, in later years. A researcher who spent a good deal of time looking for the first Simpson in America believes John Simpson, a Scotsman, settled in Stafford, Virginia late in the 1600’s. This would put the Simpson family in the company of the Smiths on the Great Neck in Westmoreland County.

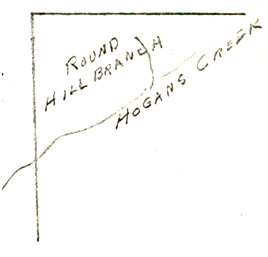

Peter Smith purchased 202 acres of land from George Counts in Orange County, North Carolina. The sale was registered at the Inferior Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions held in Corbin Township in November of 1764.[3] Caswell County was hatched out of Orange County in 1777 and Peter’s property was in that part which became Caswell County. His land was on the north side of Hogan’s Creek, on the Round Hill Branch of Hogan’s Creek.

Peter Smith purchased 202 acres of land from George Counts in Orange County, North Carolina. The sale was registered at the Inferior Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions held in Corbin Township in November of 1764.[3] Caswell County was hatched out of Orange County in 1777 and Peter’s property was in that part which became Caswell County. His land was on the north side of Hogan’s Creek, on the Round Hill Branch of Hogan’s Creek.

Peter Smith went to war on the side of the patriots of North Carolina during the Revolutionary War.[4] In all likelihood he fought alongside the William Davis family members in our tree and the Williams family in my wife’s tree, all Carolina patriots. It was customary for war veterans to submit applications seeking payment from the founding fathers for service rendered during the war. Payment could come in the form of pounds and often deeds to land west of the Appalachian Mountains. Peter’s certificate reads as follows:

“Peter Smith. No.592. State of North Carolina, Hillsborough District. Auditors office the 7th day of August 1782. This day certify that Peter Smith Exhibited his claim and (was) allowed fourteen pounds six shillings and pence. (Signed) John Nichols.”

Peter Smith died in 1797 in Caswell County; his will was dated April 18, 1793. It is assumed that Jemima preceded him in death as she was not mentioned in the will. I have attached Peter’s will in this blog. Numerous children are identified: Elizabeth, Martha, Jesse, Moses, Aaron, James, William, Pressley, George Rudolphus Smith, John B., Elias and Elijah. They needed a school bus to get to church. Once again, we have a number of slaves moving from one household to another: Jane (along with a horse and saddle) ends up with Elizabeth. Bess and another horse head off to the home of Martha. Son Jesse gets possession of a boy named Lewis, Moses gets Edmond and Aaron gets a girl named Fannie. And then there is a reference to “other property consisting of land, negroes, stock, household furniture, etc.”

What is most interesting is a passage regarding

“my Negro Anthony who though not absolutely free, I will that he have liberty to have his own choice from time to time, to serve which of my children he shall choose, and not to be confined to any one particular, but if ill treated by one, to have liberty to go to another as he shall see fit, and not to be sold to any other person.”

Peter appears to have a high regard for Anthony and grants the man some autonomy not commonly found within the bounds of enslavement. Why didn’t Peter just give the man his freedom? There were periods of time in North Carolina history in which it was illegal to free a slave. It created confusion for the white folks who were responsible for rounding up fugitive slaves. A freedman had better carry the paperwork from the master who freed him (or her). White folks were also nervous about the damage a freed black person could do to the economic system in which the whites made their profits and living. A black man moving freely about the county could create insurrection among slaves, and at the very least, create envy among slaves who dreamed of freedom. Peter’s will may have been written at such a time in history. Again, it seems like a nice gesture on Peter’s part, but hey… Anthony remained a slave. Tough to think about.

Peter and Jemima Smith are also believed to have had a son named Robert, a preacher, and a daughter Susan, although they are not named in the will. In all likelihood they preceded their father in death.

A History of Muhlenberg County (Kentucky), by Otto A. Rothert, 1813, states that Paradise, Kentucky, is one of the oldest places in that county. It is about a mile from Old Airdie (named for a town in Scotland), and is built on land first settled by Pioneer Leonard Strum (or Strom). Rothert notes that among the first settlers in this neighborhood were three of the sons of Peter Smith of North Carolina: Aaron, James and Elias. Records show that eight sons of Peter and Jemima Smith eventually moved to Muhlenberg County, where some or all of them obtained land. They were (first and middle name): James Simpson, Moses F., John Bailey, Pressley Wheeler, William Wigginton, Elias Guess, Aaron Fairfax and Jesse W. One of the daughters, Martha, also made the move. From Round Hill to Paradise KY was a 430 mile journey without benefit of a UHaul and through the Cumberland Gap into hostile lands. All of those making the journey were certifiably sane and taking their chances, as we will see.

Chapter 7: The Role of Smiths in Shaping Religious Freedom

Charts of the Family Tree are found at:

Smith Family Tree Descending from George Rudolphus Smith to the present day, (1750-2015)

Smith Family Tree Descending from Peter Smith of Westmoreland to George Rudolphus Smith (1641-1775)

FOOTNOTES

[1] DAR Patriot Index, 1966, p. 628

[2] Fairfax County, Virginia, Will Book D, p. 292

[3] Orange County, North Carolina, Registration of Deeds, 1752-1793, Part II p. 16

[4] DAR Patriot Index, p. 628

NOTE: I found the location of Round Hill on Hogan’s Creek in Caswell County in North Carolina by using Google Earth and those keywords. From space it looks like a mix of forest and farm land, on the Virginia state line. I also used Google Earth to find Cople, Yeocomico, Nominy in Westmoreland and to locate Paradise, Kentucky where nine of our clan relocated.

How did Peter Smith’s descendants remain out of the picture when the Founding Fathers congregated in Philadelphia and New York? Easy, the Smiths were heading north and west and carving out a new frontier while their cousins carved out a new Constitution. And don’t think these guys didn’t serve their upstart rebel nation. There were Revolutionary War battles to be fought in the Northwest Territory of Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and in the hills of Appalachia at Cowpens and Kings Mountain.