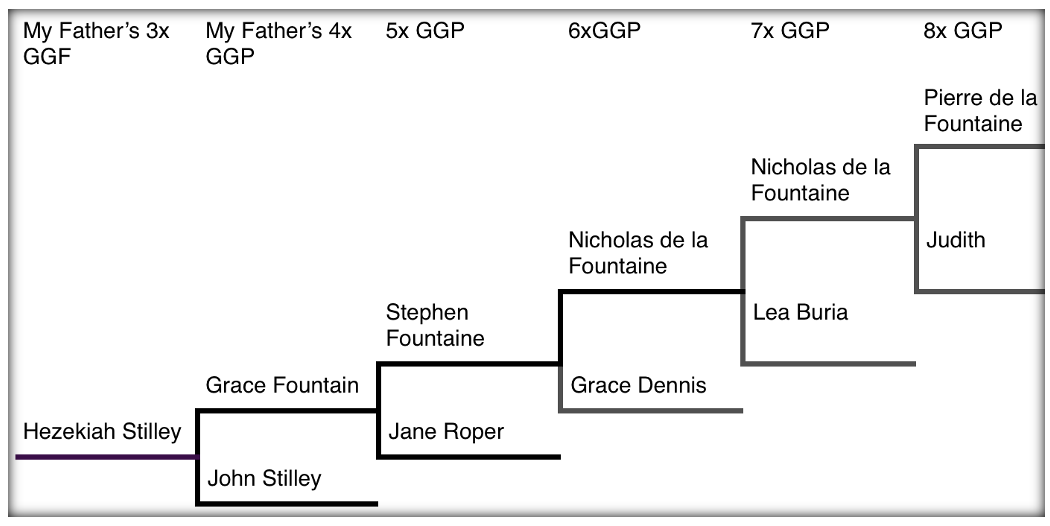

Gen 8: John Stilley (1715-1795) and Grace Fountain

My Fathers’s 4th Great Grandparents, Somerset MD to Beaufort NC

John Stilley, Hezekiah’s father, married Grace Fountain, daughter of Stephen Fountain and granddaughter of a French Huguenot immigrant named Nicholas de la Fountaine.

Grace de la Fontaine Americanized her name and traveled through her maiden years as Grace Fountain. Her descendants used the name ‘Fountain’ as both a first and middle name when they named their children. There was a reason for the pride they took in keeping the memory of the de la Fontaines alive.

Grace’s mother was Jane Roper of Manokin, Somerset, Maryland. The surname Roper also appears in colonial history as ‘Raper’ but that spelling became increasingly unpopular over the years as the term took on new meaning in American culture. Grace’s grandparents, Nicholas de la Fountaine (1638-1708) and Joanna Law, arrived in Maryland in 1663.

“On July 13, 1665 Nicholas Fountaine, late of Virginia and subject of the crown of France, was granted denization by Maryland.”

‘Denization’ indicates that Nicholas was granted status as a naturalized citizen in Somerset County. He had previously been identified as a native of France. The de la Fontaines were victims of the horrific persecution of the Huguenots in France. I have debated where that information should go in this volume and think I shall end the one-sided conversation with myself by placing it here. We can come back to the Stilley family in a few pages.

Nicholas de la Fontaine of Normandie, France, was part of the protestant reform movement, and fled from Catholic persecution with his wife and son Nicholas to London, where they were active members of the French Reformed Church of Threadneedle Street. While in England Nicholas and his wife had six more children.

Nicholas, Jr migrated to America in 1658 and settled near the Manokin River in Somerset Co., MD. He was granted 300 acres of land on the Manokin River and named his plantation Fountains Lott. He added another 50 acres which he called Normandie. Before his death he had acquired 8 plantations including: Winders Purchase, New Rumsie, Rumney, Peake, Nova Francia and Double Purchase. All these properties stood on the banks of the Manokin River.

Pedigree Chart 9: The de la Fountaine Family (The French Connection)

In the book, Old Somerset on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, author Clayton Torrence conveys the following information.

“Men of the church came into the Manokin section of this Eastern Shore of Maryland in the late Fall of 1661 and early Spring of 1662, as did a majority of the first planters of Manokin. Nicholas Fountain was settled in Manokin by May of 1662. He was but one in a line of French Huguenot aristocrats who had been expelled from France. He came from a hearty line of devout protestants.”

John De la Fontaine was born in the province of Maine, circa 1500, and as soon as he was old enough to become a soldier, his father used his connections to get John a commission in the household of Francis I, King of France. John was a skilled officer in the military and gained the trust and admiration of the King. In fact, John was so tight with the King that John’s father was able to preach as a Protestant in 1535, when Catholic France was actively persecuting protestants.

John De la Fontaine continued in service to Kings Henry II, Francis II and Charles IX. John earned the scorn of Catholic clergy and political powers who wished nothing better for him than death. He exercised the powers of his office to assist the poor Protestants, many of whom he had shielded from persecution. John retired from his military service to the kings of France and father’s estates in the capital of Maine, Le Mans. He wrongly assumed he would be safe-guarded from persecution.

John was among many targeted by his sworn Catholic enemies. The Catholic clerics and politicians really did harbor a deep hatred for the guy. Now that he was no longer protected by his alliance with the King he was viewed by the Catholic Church as a man worthy of elimination. A contract was put out on his life. John and his family were at home near Chahaignes in the late evening of May 10, 1563. His home was invaded by a team of assassins. Clayton Torrance reports “Some ruffians were dispatched from the city of Le Mans in search of him; and in the night time, when he least expected such a fate, he was dragged out of doors and his throat cut.”

His wife, who was very pregnant, went after the mob to plead for John’s life. She too was assassinated along with a manservant. Their bodies were thrown into a limestone pit. The fate of John de la Fontaine’s oldest son is not known. His three young sons fled into the night, orphaned and terrified, and made their way to La Rochelle.

From the year 1534 to April 1598, the persecution of protestants was routine and required all types of injustice and cruelty. One could not properly claim to be a protestant if they didn’t have a few scars to show for it. A temporary end to the routine was created when Henry IV of France granted the Edict of Nantes, which proclaimed that there just might be more than one way to relate to God. That edict was pronounced law in 1598 after a century of hate mongering and death by dismemberment on the infamous rack. It was all done in the name of God and by the book, the good book in fact. Funny how that Bible became one of the biggest weapons used by man to destroy mankind.

Nicholas de la Fontaine was a Protestant refugee in Geneva and entered the service of John Calvin, by whom he was employed as a secretary. De la Fontaine brought Michael Servetus to trial on August 14, 1553 on the charges of heresy against Calvinism. Calvin was incapacitated with various health issues and did not present his case against Servetus. Instead he drafted 40 charges against Servetus and charged Nicholas with the responsibility of presenting the case against Calvin’s arch rival, Servetus. Over the decade Servetus’ pamphlets, sermons and opinions cut into Calvin’s base. From Calvin’s point of view, Servetus was doing the devil’s work and leading people away from the church, God, Jesus and salvation.

The French courts at the time required that both plaintiff and defendant be held in jail during the time of the trial. Thus, Nicholas de la Fontaine, by launching proceedings against Michael Servetus, allowed himself to be held prisoner during the criminal process. John Calvin saved himself some time in jail by throwing Fontaine in to do his dirty work. De la Fontaine did his job perfectly and Servetus was burned at the stake. It was a rare moment in family history. Normally, our ancestor faced persecution, prosecution and death.

Among the charges Nicholas lobbed at Servetus, one charge struck me as relevant in 2018: He charged Servetus with being soft on Moslems and failing to sound the alarm regarding the dangers of the Koran. That was 500 years ago. Some things just won’t change.

After a century long struggle the Catholics of France gave up on the idea of tolerating the Huguenots and decided wholesale slaughter might be the best way to eliminate the problems these dissenters created in the otherwise wonderful world of French culture and cuisine. The massacre of St Bartholomew was a perfect way to send a message that these protestants were not wanted, living among God’s Children, the devout Catholic. A little genocide can go a long way toward improving things in a world filled with hatred, intolerance and ethnocentrism.

On October 22, 1685, King Louis XIV issued an Edict of the Revocation of Nantes which removed the rights of Huguenots to practice their own religion. Reverend Jaques Fontaine, his fiancé Anne Boursiquot, her sister Elisabeth, and his niece Janette Forestier fled France for England, landing in Appledore on December 1, 1685.

Making a living in England was not be easy for Jacque. He adopted the English translation of his name, James, and did his best to assimilate into the British culture and economy. He married Anne Elisabeth Boursiquot in 1686 and together they built a home and family. They moved from Taunton, England to Cork in Ireland where he served a small Huguenot community as minister. Within a few years they moved again to the remote Beara Peninsula where he tried very hard to make a living as a commercial fisherman. He failed miserably and suffered the consequences that living to close to pirates can inflict on a man and his family. Two separate attacks by pirates created a bit of stress for his family. His son Peter was abducted during one attack and held for ransom. James paid a heavy ransom for the return of his son. He took what little he had left, removed his family from Beara and moved one last time to a small house on St. Stephen’s Green in Dublin. His home was across the street from the cemetery in which he would soon be buried.

His children hurried off to Virginia Colony and escaped the tyranny and travail, or so they hoped. John, the oldest son of James and Ann, was educated at Trinity College in Dublin and departed for the new world on the ship, The Dove. He journaled each day of his travel both on the sea and on land. His sole purpose was to explore the new land and purchase the most suitable plantation property available. He was working on behalf of his siblings and cousins.

Incredibly, and one may wonder how he pulled this off, he befriended General Alexander Spotswoods, the Virginia colony’s governor. Spotswoods was first and foremost a land speculator and entrepreneur. He was the colony’s political and economic architect. He would make a lucrative income attracting beaucoup immigrants to the colony. Fontaine accompanied the governor and a small group of men through theVirginia wilderness. They were surveying the land, moving further into the continent than any European man had done before in the Virginia territory. They went beyond the Blue Ridge and developed some swagger. They branded themselves the Knights of the Golden Horseshoe.

James Fountain journaled the entire experience and while he didn’t earn the Pulitzer Prize for his effort he provided the world with an insight into the wilderness that would become West Virginia and Kentucky. He also purchased a large tract of land from Spotswoods, land that he would subdivide and sell to any Huguenots tired of getting the crap kicked out of them in Europe. The community carried the name Manokin and prospered. While James returned to live out his life in Wales, his siblings and cousins were all attracted to the possibilities of life in Manokin and beyond.

Our own ancestors, Grace Fountain, her father Stephen and grandfather Nicholas de las Fontaine stepped out of this tragedy and eventually escaped the death trap experienced by so many French protestants. Their ancestors, centuries prior, had been major players in the French wine industry, producing vintage Bordeaux wines. Persecution did not reduce them to tatters. They would eventually find themselves 5000 miles away from the Rhone River in the hills of Southern Illinois. Fountain Stilley’s brother Elder Stephen Stilley (1765-1841) would stand at a pulpit in Makanda, Illinois and give thanks for all God’s blessings. In a pew to one side of the small church, he himself had built, would sit his brother, my 4th great grandfather, Hezekiah Stilley (1763-1840) and his wife, the equally great granny Sarah Davis.

On April 2, 1736 John Stilley and Grace Fountain had a colonial official survey fifty acres of land for them. John titled the plantation “Constantinople.” It stood on the south side of the Nanticoke river in Somerset County, Maryland. No patent was issued, implying it was a purchase.

On March 4, 1742 John Stilley was deeded twelve cattle, three horses, twenty hogs and various household furniture by Mary Stilley (his mother) of Stepney parish in Somerset County. Several land transactions involving John Stilley in Somerset County followed. It is interesting to note that John Stilley was a neighbor of my wife’s Whittington family that had moved into Somerset County, MD, from Accomack County VA. Paths do cross in a small world.

John and Grace Stilley had numerous children and in later life moved with their children to Craven County, North Carolina, where they each died sometime after 1790.