A Preface to our Dutch Ancestors

Shortly after the Dutch took possession of Manhattan Island in 1625, the corporate authorities (West India Company) created 9 bowerijs (farms); three along the Hudson River and six located further to the east along Bouwerij (Bowery) Lane. The east side farms were identified by the name of the family leasing the land from the Company: “Bylevelt’s,” “The Sellout’s,” “Wolfert’s,” “Van Corker’s,” “Leendert’s,” and “Pannepacker’s.”

Finding the name of family, in this case ‘Wolfert,’ in documents dated four hundred years ago creates a surreal moment. When I set foot in a family European castle or walk on a potato field or in a forest that provided sustenance, I feel the family presence. I can hear their voice asking deeply spiritual questions like: “What in hell are you wearing?” or “Who would eat that?”

“Wolfert” was my father’s 8th Great Grandfather. You can set aside this book right now and begin to Google his name, ‘Wolfert,’ and the search engine will find him before you type the final letter. Or, you can hang in here with me and I will give you what I have found after years of researching the man and his wife, Neeltje. This was truly a husband and wife business partnership composed of two equally talented entrepreneurs. His full name was Wolfert Gerritsen von Kouwenhoven (aka:Wolphert Gerretse von Kouwenhoven).

The Dutch agri-business records for the year 1630 can be found online. They reveal that Wolfert Gerritsen owned 4 mares, 1 stallion, 9 cows, 2 bulls and 20 sheep. The 8 farms in existence in 1630 held 186 head of livestock. Wolfert held 36 of the critters on his bouwerij, or 20% of the animal stock on the island. He was not only the largest producer on the island, but he was also the agent for the man who was buying up the livestock, Kiliaean Van Rennsselaer. Kiliaean, a Dutch diamond merchant, was the man from Corporate responsible for the push to develop farming in New Netherlands (Manhattan and Long Island, and the Hudson and Connecticut River Valleys).

Wolfert and Neeltje were so successful that corporate moved them one hundred and fifty miles north to their Albany NY offices. This move put Wolfert in charge of Van Rennsselaer’s New World agri-business operation: the Manor of Rensselaerswyck. Neeltje oversaw fur trade with the First Nation (Native American) population of both the Hudson and Mohawk River valleys. The Dutch patroon, Van Rennsselaer, never came to America, never saw the land he owned. His estate covered all of Albany and Rennsselaer counties and much of Greene and Columbia counties. Wolfert was the director of operations and recruited mid-level management as well as tenant farmers. He would send boatloads of European families into the Albany area estate.

But Wolfert and Neeltje wanted a larger slice of the action and were smart enough to use their positions to not only advance Van Rennsselaer’s position, but their own as well. Their tactics put them at odds with the Dutch governing body and any investor not named Van Rennsselaer. The Von Kouwenhovens were the first on this side of the ocean to use the now famous Walmart tactic: flood the marketplace with a product that undercuts the pricing of the established markets. They did this with livestock, grains and furs, ignoring Dutch laws, price controls and the economic structures in place. Read ahead and find out more about these shrewd great grandparents in the pages that follow.

Our Dutch Ancestors in New Amsterdam – 1626

Generations 10 thru 13 and beyond

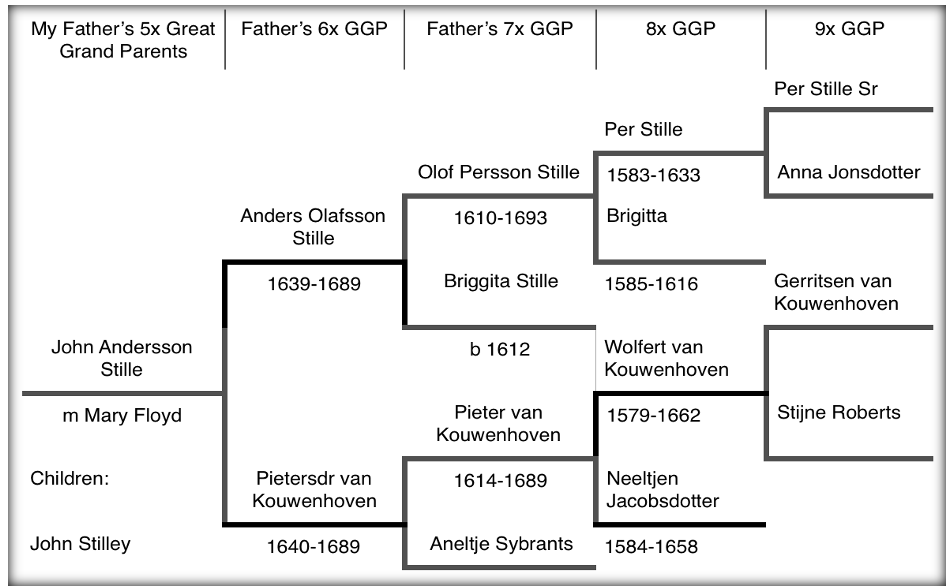

We are still in my father’s family tree. We have descended back through four centuries of time. We will soon be standing in an open field in Holland. But, to refresh your memory, we found a portal into this world of Swedes and Dutch via the marriage of Jane Stilley and James Monroe Smith. Jane descended from Olof Stille whom we have just met. Jane was my father’s grandmother. Her son Leb Smith was my grandfather. We have gone back in time through nine generations of family to find these Swedish and Dutch grandparents.

Previous Pedigree Chart 8: The Swedish and Dutch Ancestors

I will be referring to Pedigree Chart 8 as we examine the Dutch heritage made so readily available by various historians.

The portal into the Dutch roots of our tree was provided when Olof Stille’s son Anders Stille (1639-1589) married a Dutch girl, Annetje Pietersdr von Kouwenhoven (1640-1685). From this marriage sprang six children, including our own John Andersson Stille (1683-1774).

The name Annetje Pietersdr von Kouwenhoven provides a clue as to her identity. My name Steve Smith tells you nothing, nada, zelch. In fact, my name is so damn popular that at least 50,000 men in the midwestern states alone have my name. Bastards! If my father, James D. Smith, had followed Swedish and Dutch conventions I would be Stephen Jamesson von West Chicago. That would be unique. Annetje is Pieter’s daughter and they were of a bowery (Dutch plantation) named Kouwenhoven. That ‘dr’ tacked on to the end of Pieters, making it Pietersdr, tells me Annetje is Pieter’s daughter. The ‘dr’ is short for dotter or daughter in English. The Dutch and Swedes used a variety of abbreviated clues that help track family lineage.

The full name for Annetje’s father was Pieter Wolfertssen von Kouwenhoven (1614-1689). So, using what we are learning about naming Dutch children: Pieter was Wolfert’s son and they were originally from Kouwenhoven. Pieter was born in Holland and his father’s name was Wolfert Gerritsse von Kouwenhoven, a respected supervisor for a bowery (farm). He was a supervisor on the Kouwenhoven estate of the De Wijs family near Amersfoort. His management position earned a fair living. But family interests were diverse. Wolfert and his wife, Neeltjen, also operated a bleachery (laundry) and they could be found cleaning and starching the clothes of the aristocrats.

Wolfert acquired mortgages, built up a little capital and learned to flip properties. It wasn’t long before Wolfert caught the eye of the financial geniuses who would lay the foundation for New York City. Wolfert was one of the best farm supervisors in Holland. He understood animal husbandry and managed people well. He also understood finances and the business world. He established a fine reputation in Holland and he soon played a leading role in the development of Manhattan Island and Wall Street. This is part of our family history and can be verified online.

On January 17, 1604 Wolfert married Neeltjen Jacobsdochter in the Tower of Our Lady, a Dutch Reformed Church in Amersfoort, Holland. Her parents were Jacob Petersz and Metgen Jacobsdr. The ‘sz’ at the end Petersz, tells us Jacob was the son of a guy named ‘Peter’. The ‘dr’ on the end of Jacobsdr tells us Metgen was the daughter of a ‘Jacob’. Neeltjen was born circa 1584 in Netherlands and she may have died in 1656 in New Amersfoort, Kings County, New York. She may well have been a victim of a war her sons instigated.

Wolfert and Neeltjen left a paper trail of Court records, including deeds. On December 15, 1611, in the settlement of Neeltjen’s parent’s estate in Amersfoort. Wolfert tells the court that he is a baker. Our ancestors often used a mark, a seal to identify themselves on official records. Family crests were used by nobility. Wolfert signs paperwork with his stylized ‘A” to distinguish himself as Wolfert Gerritse from Amersfoort. The documents provide assurance that he accepts the property and debts of Neeltjen’s deceased parents. The document also identifies her brothers Herman and Peter, as well as a brother-in-law, Willem Dircx.

Wolfert and Neeltjen lived at the Kouwenhoven estate in Hoogland, smack dab in the middle of the agricultural province of Utrecht in Holland. In addition to being a baker, he was also a tenant farmer. The De Wijs family was granted rights to the land by the feudal Lord of Montfoort. This pattern of land ownership evolved over the middle ages in Europe and carried into the New World. There are many examples of this in our own Smith family in Culpepper’s Great Neck VA, and the Davis family in North Carolina. Patents helped establish the Smith family at Bull Run VA and the Round Hill Plantation in Caswell County NC. Tracts of land were frequently purchased as parcels of larger patents typically held by nobility, aristocrats or the nouveau riche of Europe.

In some cases, the powerful landlords seized the property of Smith ancestors as our ancestral Butler family did when they slaughtered and removed our Fitzgeralds, O’Byrnes and Hughes ancestors from their small farms in Ireland. And as our Scotch Irish, Dutch, British, Welch ancestors did when they came to the New World and removed the Lanape, Cherokee, Shawnee and a multitude of tribes from their sacred hunting grounds. It is life in the fast lane, survival of the fittest, all the clichés about the rich getting richer….

The Dutch were meticulous when it came to creating paperwork. There is no ancestor in our tree with more documentation available than Wolfert. A series of financial transactions, investments and deals culminate with Wolfert and his family leaving Europe for New Amsterdam, located on present day Manhattan Island. The trail of paperwork begins on April 14, 1615 in Amersfoort, Netherlands. Wolfert took part in what appears to be the settlement of a debt owed him. In the court of Johan Van Ingen in Utrecht, Herman Zieboltz gave Wolfert two morgens (2 to 5 acres) of turf near Cologne in recognition of services rendered. No monetary amount is mentioned for the services or the turf ground. Apparently Zieboltz was unable to pay Wolfert money owed him and Wolfert may have agreed to accept the turf as payment enough in his business dealings with Zieboltz.

On May 16, 1616, Wolfert Gerritse, identified as a baker, again appears as a witness in Van Ingen’s court. On this occasion he represents his brother, Willem Gerritse, a miller by trade. Willem and Wolfert testified that Griet Maes was evading the city grain tax. While Willem is not identified in the court record as Wolfert’s brother, Wolfert did have a brother named Willem Gerritse living in Amersfoort.

On October 28, 1616, Janss and Haesgen Thonis made the final payment on a bleach camp they purchased from Wolfert. So Wolfert was also known as a bleacher (a 1615 laundromat operator). A bleach camp was a capital intensive, seasonal business which required the labor of many skilled workers. Three types of bleach camps could be found: wool, clothing and woven fabric. In each case the material was first cooked in a lye solution, and later spread out on green grass for many weeks in small fields surrounding the bleach house where the fabric was kept damp. The fabric was then cooked in a solution of wheat meal and laid out once again on the field for a lengthy period. The entire process required about three months. Only wealthy people could afford the services of clothing bleachers. Imagine, waiting three months to get your shirts back from the dry cleaners! Rich folks had a summer wardrobe and winter clothing.

On January 30, 1617, Wolfert and Neeltjen bought a home at Langegraft, Amersfoort, Utrecht, Netherlands. They purchased the home from Aert Van Schayck and his wife Anna Barents. Records pinpoint the location of the house on Lieverrouwestraet (Dear Lady Street). The house was next door to Hednrickgen Speldemaeckster. Deeds often identified properties in relationship to the neighbors, landforms and vegetation (e.g. trees).

Within two weeks (February 15) of the purchase of the Langegraft home, Wolfert and Neeltjen began borrowing money at a pace that indicates they had a plan:

–They borrowed 100 guilders from Armen te Amersfoorton and agreed to repay the debt at 6 guilders per year. There is no additional detail. Other financial arrangements indicate that 6 guilders was probably an interest rate on the principal.

–On May 16, 1617, Wolfert borrowed another 200 guilders from Cornelis Baecx van der Tommen at a yearly interest of 12 guilders.

–On Jul 25, 1617, Wolfert borrowed 250 guilders from Anna Goerts widow of Franck Frandkss at 15 guilders interest per year.

Only 18 months after selling a bleach camp, Wolfert and Neeltjen purchased another bleach camp outside the Coppelpoort of Amersfoort. Hubert Lambertsz Moll and his wife Geertgen Cornisdochter are identified as their business partners. This may be the reason Wolfert was borrowing to the hilt.

On September 17, 1618 Wolfert and Neeltjen mortgaged their Langegraft house. The former mayor of Amersfoort, Coenraet Fransz, provided 100 guilders at an annual interest of 6 guilders, with “the house of Wolfert on the Langegracht as security.” Within a short time, Wolfert mortgages the house three times. Gambling debts? Nutella addiction? Who knows?

Wolfert’s brother Willem died prior to November 5, 1622. Records indicate that Wolfert was appointed guardian of the five minor children Willem left behind. We see this time and again in family history: brothers taking on responsibility for a deceased family member’s child. Court documents in this matter refer to Wolfert as a “bleacher residing by the Koppelpoort (a bridge) and Harmen Willemsz citizen of Amersfoort as ‘bloetvoochden’ (blood guardians) of the five sons of Willem Gerritsz Kouwenhoven.” The children are identified as: Gerridt, Willem, Jan, Harmen, and Willem the Younger. Harmen would appear to be of legal age as he was identified in the court document along with Wolfert as a guardian. The arrangement is agreed to by the mother of the children Neeltjen Willemsdr (the widow of a Willem). The honorable Johan de Wijs owner of Cowenhoven Estate provided assistance. The document indicates that Wolfert‘s brother Willem had also been a tenant of the Kouwenhoven farm, owned by Johan de Wijs.

Koppelpoort Bridge

Wolfie’s Bleacherie was near the Koppelpoort Bridge, 400 years ago. A 9 times great grandfather toiled for a living with his business partner and wife, Neeltjen, on the shores of this stream. It is not unusual to find police reports and complaints about citizens in the Dutch archives. Some entries are humorous, some very criminal in nature and some defy reason. A many times great granduncle was put to death for stealing a basket of peas from a porch in Britain.

In the case of Wolfert we find the crime involves a bucket of fish. On March 24, 1623, a man by the name of Beernt Van Munster filed a deposition under oath at the request of the police officer. Beernt testified that on the previous Saturday afternoon he had caught a bucket of fish by the Koppelpoort Bridge. He had given half of the catch to ‘Wolfert the bleacher’ per an agreement. After dividing the catch with Wolfert, Beernt went back to fishing again and caught an additional small number of fish. He had no intent of sharing these additional fish with Wolfert. Wolfert and his brother, Harmen Teut, then took these fish from Beernt and refused to give him any of his most recent catch. Wolfert kept Beernt’s net and tried to give it to his wife. Harmen hit Berrnt in the eye with a weight in the net, and the net was ripped. Beernt then went to the defense of his wife, and Wolfert drew his knife and threatened him without harming him. Beernt then testifies that, “Dirck Gerritsz, stevedore, using well-chosen words, separated the people from each other.”

On April 1, 1623 in a follow up to Beent’s complaint, Dirck Gerritsz provides testimony at the request of the investigating officer and submitted a similar deposition under oath. This fishing expedition is the last of the documents related to Wolfert Gerritse in the archives of Amersfoort. From this point forward, his trail leads us to Flatbush, Brooklyn (New Amsterdam) and his development as a Manhattan wheeler dealer. Because of the extraordinary richness of the evidence I feel compelled to point to the number of books and articles cited as sources in the appendix of this collection.

Gen 12: Von Kouwenhovens: Crossing the Atlantic

The von Kouwenhovens were Dutch, with roots in Amsfoort, Netherlands. Wolfert was a jack of all trades, as was his wife Neeltjen. Rotterdam, Holland was a financial district for the world at that time (1620) and a bustling port offering international trade and endless opportunities. The sea was an open highway, inviting dreamers and schemers to seek adventure and fortune along a new world seacoast that ran from Brazil to Nova Scotia. Wolfert had been working “24/7/365,” four hundred years before the phrase would become popular. He was a workaholic with one gear and one gear only, overdrive. Neeltjen was an equally accomplished person and perhaps the driving force in the family. Destiny was knocking on the door.

In the annals of history, the story of New Netherlands is a short but very important piece of American and world history. The first recorded European guys to set eyes on the Hudson River sailed with Giovanni da Verrazano in 1524. Giovanni had already traveled up several estuaries along the American coastline. None of those estuaries had panned out as a route to Cathay (China). Intuition told Giovanni the Hudson River would not afford him a passage to the Orient. In 1609 Henry Hudson, in search of the still elusive Northwest Passage to Cathay did sail up the river that would eventually take his name. He went north as far as Albany NY and concluded two things: 1) This wasn’t the passage he was hoping to find and 2) there were a whole lot of beaver pelts to be had for a profit back in Europe. Throw in some mink and otter and a guy could turn a fortune in fur.

The Frenchman Jacque Cartier had initiated a limited fur trade with Native tribes along the St. Lawrence River in the 1530’s. Nearly 100 years before Pilgrims landed at Plymouth, Basque cod fishermen dried their catch on the Newfoundland shoreline and were acquiring beaver pelts in trades made with the local nations. Eventually the European market paid attention and the beaver pelt became a booming commodity. The Dutch, including Neeltjen von Kouwenhoven, developed lucrative partnerships with Native populations. The Natives were especially interested in trading pelts for guns and alcohol. This created some bad karma down the line.

Henry Hudson named the river Mauritius, after Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange, the man who led the Dutch revolt against Spain in the early 1600’s. The name didn’t stick. The Dutch held a strong interest in developing the lands that Hudson had claimed on their behalf. They colonized the Delaware estuary, which they called the South River and the Hudson River Valley which they called the North River. Their efforts in the Delaware River settlement brought them into conflict with Olof Stille and his Swedish community (New Sweden). Their efforts to the east, in the Connecticut River Valley brought them into conflict with the British and our Puritan families. Efforts to the north, along the Hudson River brought conflict with the Native nations.

The colony of New Netherlands began as a harbor sheltering Dutch merchant ships operated by pirates, armed by the military industrial complex of the Netherlands. As part of the effort to liberate their Dutch homeland, Netherlands, from Spanish control, the Dutch had to cut off the New World shipments of gold, silver and sugar that were providing a revenue stream for the Spanish war machine. Dutch ships inflicted serious damage over the decades, capturing over 500 ships and 30 million guilders of coin. An interesting argument was taking place in the corporate board room of the Dutch West Indies Company. Rumors that the Dutch and Spanish might resolve their differences and live peacefully together created panic for those among the Dutch who made their profits from war.

Agriculture in New Netherland could not reap the return on investment that Dutch investors needed. In fact, agribusiness ventures in New Netherland created red ink, a drain on corporate budgets. And yet, colonization would be necessary to protect Dutch interests on a global scale. The failure to colonize their holdings in Brazil had already cost the Dutch the world’s finest sugar harvests. The Spanish quickly established a pattern of knocking off British fortresses in the New World. There was a reason why Jamestown had been secluded upstream on the James River in Virginia. The Brits did not want to draw attention to their efforts.

A fortress and troops would be necessary to protect the New Amsterdam port facility. A series of forts along the Hudson River could also extend Dutch interests in the territory and create opportunities to befriend the Native population. Military alliances with New World nations could follow. Such was the pipe dream in the Rotterdam headquarters.

New Netherland expanded as a series of trading posts and crude forts with garrisons established to protect Dutch piracy, trade, and military interests. The forts were positioned from Schenectady (now NY) 400 miles south to Swaanendael, Delaware and east into the Connecticut River Valley (present day Hartford). The Dutch West India Company brought back a lot of fur in their first year of operation. The value of that harvest was subject to scrutiny by the Company bean counters. Corporate executives realized that the fur trade would not bring the profits investors needed if peace prevailed and the production of military hardware ceased. War machinery was where the money could be made. Can you say Halliburton?

Unsure of their relationships with local tribes and financial spreadsheets, the Dutch were slow to colonize, to add settlements. However, the obvious efforts of the Spanish, Portugese, British and French to carve up the new world left the Dutch and Swedes with the realization that a stake in the new world would require colonization. Fortresses would require soldiers and services including food, shelter, and other items necessary for survival. For an interesting perspective on the Dutch corporate approach I point you to Donna Merwick’s The Shame and the Sorrow: Dutch-Amerindian Encounters in New Netherland.

In 1624, at age 40, Wolfert signed up with the Dutch West India Company for service in the colony of New Netherland. Within a year Wolfert and Neeltjen set sail in the company of four ships in the Verhulst Expedition, bound for New Netherland. The company ship was loaded with 700 tons of humanity, mackeral, horse, cow and sheep. Documents indicate the ship had a crew of 200 people and 32 cannons. It was an era of piracy on the high seas and there was no such thing as a safe cruise. The cannons were necessary to ward off attack. Ships were being captured and passengers taken hostage and traded as slaves in Portugal, Spain and North Africa. Our ancestors, James and Robert Davis captained ships for Britain and their ships had already experienced such peril.

The “crew of 200” included colonists who would settle in and develop New Amsterdam and the Dutch patents throughout New Netherland. Wolfert was listed as one of five head-farmers in the expedition. His experience as a tenant farmer/businessman at Kouwenhoven had caught the eye of management. The five head farmers were identified in company documents as Walich Jacobsz, Jacob Lourensz, Matthew de Reus, Wolffaert Gerritsz, and Jan Ides. “Wolffaert Gerritsz” was yet another way of identifying Wolfert. Notice that the ‘sz’ and ‘se’ suffix are used interchangeably within a family and even for one individual person.

Instructions for the journey were laid out in writing by the directors:

“The cattle, horses, and other animals shall remain undivided during the voyage and in that country be distributed by lot, under the direction of the Council, to the head-farmers with the drawing of lots each one shall have to be content, it being his duty to care for the allotted animals to the best of his ability, without disputing about the matter in the least, on pain of being punished therefor by judgment of the Council. To each head-farmer and his family shall be allotted four horses and four cows to be selected from the best that are being sent over, and the rest and the others belonging to the Company shall be dealt with as explained hereafter.”

Nicholaes Janszoon Van Wassenaer gave a detailed account illustrating the traditional Dutch orderliness and cleanliness on board the ships to New Netherlands:

“Each animal had its own stall, and that the floor of each stall was covered with three feet of sand, which served as ballast for the ship. Each animal also had its respective servant, who knew what his reward was to be if he delivered his charge alive. Beneath the cattle-deck were stowed three hundred tons of fresh water, which was pumped up for the livestock. In addition to the load of cattle, the ship carried agricultural implements and all furniture proper for the dairy, as well as a number of settlers.”

The Verhulst Expedition established the first farms and settlement on Manhattan Island in 1624. Wolfie’s arrival several years after the Mayflower docked in Plymouth, precedes Olof Stille’s arrival in New Sweden by 15 years. The Dutch colonies were well financed by the heavy hitters of Netherlands. The land leases (patents) on Manhattan Island ran for six years in the manner of the patroonship established by the Dutch. Wolfert’s previous experience working the Kouvenhoven estate in Amersfoort was invaluable to new world settlers. The Dutch learned something from the bitter experience of the British at both Jamestown and Popham Colony (Maine). Our ancestors John and Robert Davis, and Stephen Hopkins were instrumental in saving colonists at each of those sites after bitter start up experiences.

Wolfert was assigned to supervise operations on the company’s farms at Bouwerie Three. The Dutch term ‘Bouwerie’ was anglicized decades later when the British took ownership, and is known today as the Bowery section of downtown New York City. Imagine living there four hundred years ago! Or even 100 years ago.

Wolfert and Neeltjen’s talent as entrepreneurs blossomed in Manhattan. While Wolfert supervised a successful farm operation and began dealing in real estate, Neeltjen engaged in fur trading, long before Wall Street bartering dominated corporate America. Her successful tactics are obvious in this letter from the West India Company secretary to the Company in Holland:

“We live here very plainly; if there is anything to be had it is the colonists who get it. It happened one day that the wife of Wolfert Gerritsz came to me with two otters, for which I offered her three guilders, ten stivers. She refused this and asked five guilders, whereupon I let her go, this being too much. The wife of Jacob Lourissz, the smith, knowing this, went to her and offered her five guilders, which Wolfert’s wife again told me. Thereupon, to prevent the otters from being purloined, I was obliged to give her the five guilders. Should your Honors desire to remedy such and other similar practices, it will be necessary to send me and the Schout and other instructions and to order the Council to assist us better.”

A ‘Schout’ was a local official.

In 1629 Wolfert sailed back to the Netherlands to renegotiate his contract with the Dutch West India Company. On January 8, 1630, while still in the Netherlands, he signed a six-year lease with the company for Bouwerie No. 6 (about 91 acres). Two weeks later Patroon Kiliaen Van Rensselaer, a wealthy jewelry merchant and director of the West Indian Company picked up Wolfert’s contract and made him the manager of his vast estate. Wolfert was now supervising thousands of acres along the North (Hudson) River including most of present-day Albany.

Van Rensselaer, an absentee landlord, realized from the beginning that the success of his enterprise, the real estate market, depended on self-sustaining farms and that a trading post was unlikely to prove profitable over time. Consequently, he forbade his agents and employees to enter the fur business and urged them to establish families on farms. He also understood that Wolfert Gerritsz was not only familiar with conditions in New Netherland, but he was also an experienced farmer. In a follow-up instruction to Bastiaen Lanssz Crol, van Rensselaer directed Crol and Wolfert to make every effort to secure the lands surrounding Albany along the North River and have the house built at the place he dictated. Rensselaer sent Wolfert back to New Netherland with his first settlers on board the ship ‘de Eendracht’ (The Unity), which set sail on March 21, 1630, and arrived at New Amsterdam on May 24th, a two-month journey.

Within 18 months, on January 9, 1632, von Kouwenhoven wrote to van Rensselaer in Amsterdam asking to be released from his 6-year contract. The administrator in New Amsterdam, Coenraet Notelman, a cousin of the Patroon, van Rensselaer, recommended termination of Wolfert’s contract. Van Rensselaer accepted Wolfert’s request and did so with a friendly letter, dated July 20, 1632: “I had hoped that you would have settled in my colony, but, as I am told, your wife was not much inclined thereto.” The reference to Neeltjen makes one wonder if she refused to end her career as a fur trader as had been required by van Rensselaer. It certainly seems likely.

From July 1632 until July 1638, Wolfert Gerritse von Kouwenhoven operated Bouwerie No. 6 on the north end of Manhattan Island, known as Geurdt van Gelder’s farm. It was bounded by present day Division Street on the north, the East River on the east, Oliver Street and Chatham Square on the south, and the Bowery on the west. When Van Gelder yielded it to Von Kouwenhoven, the farm had six mares, ten cows, and a bull. Finding such a wealth of information is a tribute to Dutch record keepers and historians.

During the time Wolfert Gerritse managed affairs at Rensselaerswyck, the patroon’s cousin, Coenraet Notelman, oversaw Bouwerie No.6. But in July 1632, Wolfert Gerritsz took full charge and held the place until July 1638. His lease expired in 1636 and he then acquired a property on Long Island where he spent the rest of his life. As for Bouwerie No. 6 it was released on March 31, 1639, to Jan Van Vorst, and on March 18, 1647, patented to Cornelis Jacobsz Stille. Notice the last name. It is the first indication that our Dutch von Kouwenhovens and Swedish Stille families were about to merge.

In the mid 1630’s Wolfert began acquiring properties that would be the envy of any present-day, real estate mogul. On July 20, 1633, Andries Hudde sold a deed to Gerrit Wolfertsen (von Kouwenhoven) for 50 morgens of land at Achterveldt on Long Island.

Editor: They are here. Where do you want the guys to put the drum set?

Doc: Right there will be nice, next to the television. Yeah. That works.

Editor: We could have just used the computer to create the drum roll effect.

Doc: Please, this is hugely important. Very bigly news! Great news! Ready with the drumsticks? Cue the drum roll in five, four, three, two and NOW!

NEWSFLASH: It is now time to unleash one of the coolest pieces of family and American history one could hope to find in a family tree and the annals of time.

Drum roll please!

On June 16, 1636, Wolfert and business partner, Andries Hudde, an officer of the New Amsterdam government, received an Indian deed for a tract of land called ‘Kestateuw.’ This acreage known as the Great Flat, containing 3600 acres of arable land, much of it meadow, extended from Bedford Creek northwest to present day Foster Avenue, west to the Gravesend Village line (East 17th Street) south to present day Bay Avenue, and southeast to Gerritsen Creek.

Hudde and Wolfert named their newly acquired estate Achterveldt, meaning hinder-most field. The term ‘Kestateux’ meant ‘where the grass is cut and mowed,’ in the tongue of the native Canarsie nation. It doesn’t make clear if the Canarsie were using John Deere lawn tractors or Kubota to keep the grass ‘cut and mowed.’ My money is on New Holland farm implements.

With this purchase Wolfert and Hudde became the first European settlers to swing a recorded land deal with the Natives of Manhattan and Long Island. To this day, the deed remains the oldest existing, written record of a land transaction in Anglo-America. Wolfert had come a long way in his rise to riches. Once hard pressed to buy a home and a laundry, he now owned the land upon which the financial center of the world would be built. His first home was several city blocks from the present World Trade Center site. Wolfert didn’t waste any time putting his axe to work. He soon built a fine home behind a high palisade of upright timbers that provided a fortress for his family. They maintained a healthy suspicion of Natives and pirates alike.

The “Kestateuw” acreage was also known as the Great Flat. The deed contains six square miles in the heart of the borough of Brooklyn. The deed references boundaries including Gerritsen Creek, Bay Avenue, 17th street, Foster Avenue and Bedford Creek. Look at a map of present-day Brooklyn on Google Earth. Ask the software to take you to Gerritsen Creek and you will realize that Wolfert and Neeltjen made their dreams come true in the New World. Gerritsen Creek is now a rare green space in the New York metropolitan area: Gerritsen Creek Gateway National Recreation Area. It stands next to the Barren Island Naval Base. From baker and bleacher and tenant farmer to supervisor for the Patroon and then “Lord of Flatbush” is quite an accomplishment. Look at that Google Earth satellite view of Brooklyn and understand how many dwellings, businesses, and parks occupy Wolfert’s original land holding. How much would that all be worth today?

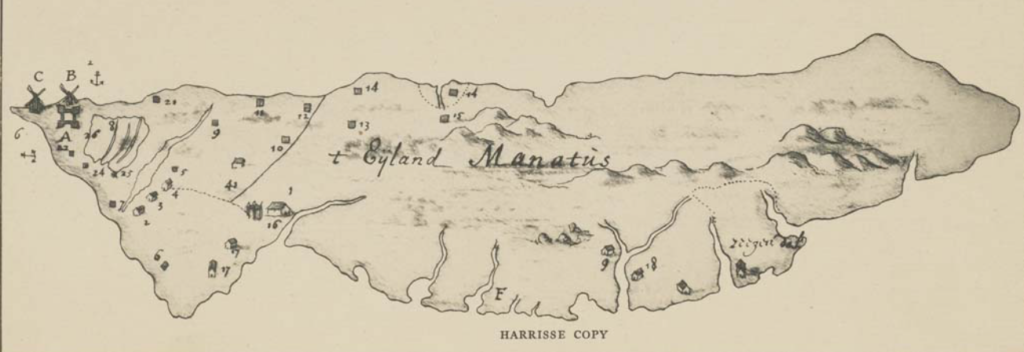

Wolfert and Andries Hudde chose the name Achterveldt for their ‘farm.’ It is identified as farm number 36 on the Manatus Map of New Netherlands. It is depicted near the Indian long house to the Kestachau tribe. As soon as the purchase was complete Wolfert and Neeltjen built a home and began to farm at the site located today at the intersection of Kings Highway and Flatbush Avenue in the community of Flatlands, Brooklyn. Again, zoom in on the street view of the intersection on the Google map and you will find a Baskin Robbins on the southeast corner, a Junior Bellas Pizza and Pasta shop on the northwest corner and gas pumps available at nearby service stations. We call it progress.

Wolfert surrounded his house with a palisade, a wall of lumber fencing that served as a fortress. He named the village New Amersfoort, and it was later called Flat Lands. On September 16, 1641, Wolfert boughtHudde’s interest in Achterveldt. Wolfert and his sons farmed the 3600 acre Achterveldt until Wolfert’s death in 1662.

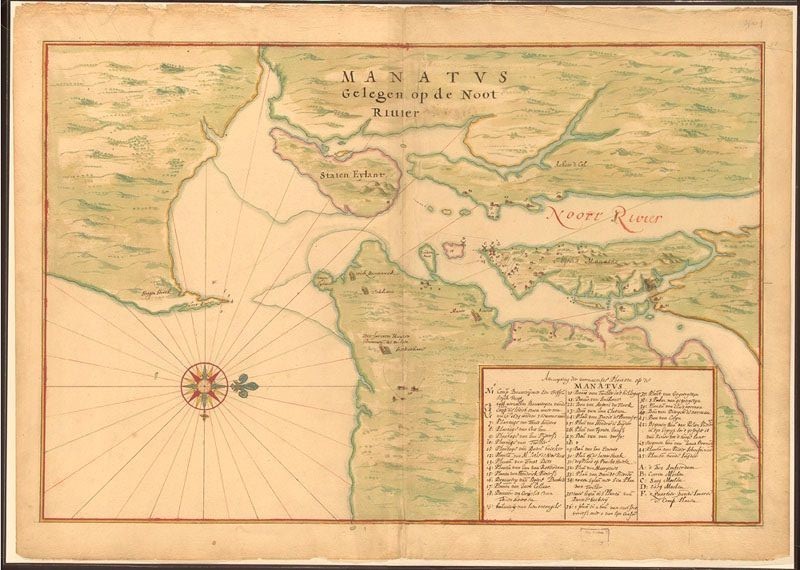

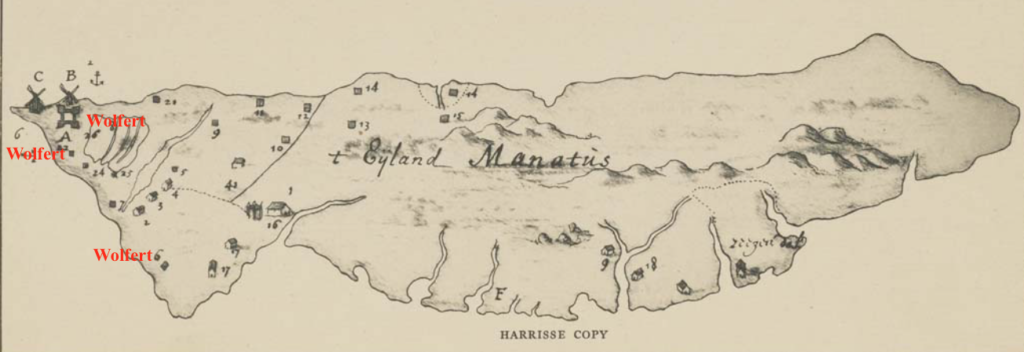

The 1639 Manatus Map

The 1639 Manatus Map, the earliest image of present-day Manhattan is the work of Johannes Vingboons. Vingboons was highly acclaimed during his lifetime as a cartographer and watercolor artist. His work was snapped up immediately by monarchs and popes. The collections are worth a small fortune. The map can be found online at the Library of Congress website. The collection from which these images can be found is also available in the complete works of I N Phelps The Iconography of Manhattan Island 1498-1909. The Manatus collection appears on this link.

When looking at the map above it is important to understand that “North” is to the right and “East” is to the bottom of this image of the map. Manhattan Island is centered to the right, just above the key (legend) in this map of the region. The legend identifies the various properties and the owners of each parcel. A Harrisse copy of the island is viewed next.

Again, many of the properties are enumerated and identified as to ownership. Wolfert Gerritsen von Couwenhoven possesses three properties, each enumerated with the number ‘6’. I have taken the liberty of defacing this historic document and point to those properties on the next map. A magnifying glass helped as did the zoom feature of the software employed.

The Manatus Map was may have been produced as a flyer circulated in Holland to encourage Dutch settlement in New Netherland. The plantations and small farms would lure the dreamer in Europe into thoughts of a new life in a Garden of Eden. Such advertising was produced all over Europe by profiteers, landlords and speculators seeking to sell off their landholdings. My wife’s Slaymakers were drawn to Krakow, Poland and into Silesia with such marketing materials and drawn again to Lancaster, Pennsylvania. My Davis, Smith, Stille, and Nancy’s Osborne, Parker and Whittington families all got the urge to pick up and move with the promise of cheap lands, fertile soil and greater freedom. Brochures drew pioneers west across the Great Plains in America. Hezekiah Stille was lured into southern Illinois, and Delos Parker (Nancy’s family) found his way to Garden Plain, Illinois.

The widely dispersed settlements in this Manatus Map are keyed by number in the lower right-hand corner to a list of land occupants. The list of references includes a grist mill, two sawmills and “Quarters of the Blacks, the Company’s Slaves.” That is correct, slaves were found in New England in the 1600s and into the 1700s. Slaves were kept on Long Island and the white masters feared the rumors of slave rebellions in New Netherland just as they did in Virginia and the Carolinas. Slavery did not really cease in the New England area until the aftermath of the American Revolution. On July 4, 1826, the last slave was freed by law, a full 200 years after the first slave arrived.

The Manatus Map shows the few roads (represented by dashed lines) and four Indian villages situated in Breucklyn (Brooklyn). The number “36” on Long Island indicates Wolfert Gerretse’s land as settled in 1639. The Manatus Map was the result of the first careful survey of Manhattan and vicinity by the colonists. It provides a glimpse into the lives of the first pioneers in present day New York.

The Dutch were businesslike in every aspect of their approach to settlement of New Netherland. A 1638 land survey reveals the von Kouwenhoven’s house

“was 26 feet long, 22 feet wide, 40 feet deep, with the roof covered above and around with plank; two lofts above one another, and a small chamber at their side; one barn, 40 feet long, 18 feet wide, and 24 feet deep; and one bergh with five posts, 40 feet long. The plantation was stocked with six cows, old and young, three oxen and five horses.”

On August 22, 1639, Wolfert Gerritse’s family responsibilities increased as he was named guardian of Lambert Cornelissen Cool. Wolfert shared those responsibilities with his son Gerrit Wolfertsen who was brother-in-law to Lambert Cornelissen. The legal document coming out of the court proceeding reveals that Lambert is asking to move out from underneath his father, Cornelis Lambertsen. Wolfert and his son testified that, as guardians of Lambert, they supported the move and

“Cannot perceive that he will earn anything, much less prosper so long as he remains with his father, Cornelis Lambertsen, we have therefore considered it advisable to permit him to do something for himself in company aforesaid.” The ‘aforesaid’ references another brother-in-law Claes Jansen with whom Lambert will “take up together some plantation or farm.”

In February 1643, several settlers, including two of Wolfert’s sons, Jacob and Gerrit, petitioned the director and council for permission to “ruin and conquer” the Indians. Director Kieft refused their request, but they did it anyway, killing several Indians. The request to “ruin” the Indians led to Gerrit’s demise. A war ensued, and much of the settlement was destroyed. Wolfert and Neeltjen survived, because his house was protected by that stockade and soldiers. The hostilities ended in 1645, but his eldest son, Gerrit (age 35) was killed during the turmoil.

On March 11, 1647, von Kouwenhoven received a patent for Rechawieck “on the marsh of the Gouwanus Kil, between the land of Jacob Stoffelsen and Frederick Lubbertsen, extending from the aforesaid marsh till into the woods….” [Patents, GG, 172] The deed goes on referencing other neighbors, points on the marsh and kil (stream). Through an accounting of morgens and rods one finally can compute the extent of Wolfert’s acquisition: sixty acres of land, or so (give or take a few morgens).

The location of the Rechawieck patent is fascinating. Wolfert bought up another stretch of Flatbush Avenue or the Kings Highway through the village of Breuckelen, down to the site where the Ferry operated. Wolfert began flipping properties, buying and selling. He sells this piece to Nicholas Jans, the baker, on the same day he bought it, March 11, 1647.

In 1652, Peter Stuyvesant, Director of the West India Company, re-confirmed Wolfert’s land holdings. Such confirmation was necessary from time to time in the colonies where government patents and trade companies were directly involved with land ownership. With the population growing, Wolfert subdivided his land and sold individual lots. Achterveldt became Amersfoort in honor of Wolfert’s native city in the Netherlands.

In 1655 several thousand area Natives went on a three-day rampage. Over one hundred Dutch settlers were killed. More than 150 were kidnapped. Neeltjen died during this time frame. Whether she was a victim of the violence is not clear. Wolfert survived. The insurrection had a decisive impact on the colony. The residents pleaded with the Dutch West India Company and the Dutch government for greater protection, to no avail. In the face of Indian uprisings, the New Netherland citizens were left feeling insecure and vulnerable. This failure by the Dutch government and the holding company would not be forgotten by the citizens when England showed an interest in seizing New Netherland for themselves.

On December 6, 1656, Pieter Wolfertsen von Kouwenhoven (my 8 times great grandfather), the son of Wolfert, asked for an injunction against the execution of a judgment obtained against his brother Jacob. It appears that father Wolfert had co-signed a debt Jacob incurred. Pieter objected to any collection against his father until his mother’s estate had been distributed to him and to the estate of his deceased brother Gerrit.In other words, Pieter was afraid his father would consume Neeltjen’s estate, a part of which she had willed to her sons. Wolfert spent his life borrowing, buying and hustling for a living. His lifestyle was catching up with him.

On April 18, 1657, Wolfert was granted Small Burgher rights, one of the first to receive this recognition in New Netherland. This entitlement allowed him to conduct business in New Amsterdam. Through this privilege, he provided his neighbors with merchandise, credit and capital. His ‘store’ became both the economic and the social hub of the community.

Between 1657-1668, New Amsterdam created a system of citizenship, meant to protect the interests of the citizen against the commercial competition of non-resident traders. The system was a carry-over of the European caste system. The colony had its slaves, indentured servants, freemen laborers, craftsman, artisans and they recognized ‘great burghers’ and ‘small burghers’. A great burgher was a super-sized small burgher, sort of a Quarter Pounder with Cheese. This confirmed the pecking order in the colony. The most powerful families in the colony maintained their status and pocketbooks. The title of ‘great burgher’ was hereditary and allowed one access to the highest public positions in the colony. Democratic principles did evolve. Everyone could become a citizen of both types, if certain requirements were met and with the payment of a fee, a bit like buying a seat on the stock exchange. In 1657, 216 folks became ‘small burghers’ (sliders if you like the hamburger analogy). At this time Wolfert’s sons, Jacob and Pieter, had each been given the rare status of Great Burgher. For a listing of Burghers, Mayors, Aldermen please go to the Burgher Chef website.My bad.

On August 27, 1658, Pieter was granted a status of schepen (alderman) and named a member of the court, he again mentioned his father’s guarantee and said that his mother Neeltjen’s property “is not yet divided.” We haven’t a clue as to why Neeltjen’s will had not gone through probate. We have no idea who was delaying action on her estate.

On October 20, 1661, Wolfert Gerritse von Kouwenhoven was named in a suit filed by Frans Jansen regarding a dispute over a contract in which Jansen was to buy land from Wolfert. At some time between March 2, 1662, when an action was recovered against him, and June 24, 1662, when his heirs were sued for non-performance, Wolfert Gerritse von Kouwenhoven died. The estate was still unsettled as late as May 27, 1664, when Covert Loockermans sued for debt and was informed by the New Amsterdam Court that nothing could be done as the money and property “do not rest here in this place.” At his death Wolfert had seen New Netherland grow from a military port and small trading post to a colony of free men and women with the right to own their own lands, conduct business and exercise a voice in local affairs.

The history of New Netherland ended for a moment in time as the British, in keeping with their imperialist tendencies, swept in with their navy to claim the Dutch colonies as their own. On August 27, 1664, four English frigates, sailed into New Amsterdam’s harbor and demanded New Netherland’s surrender. The previous failure of the Dutch government and the West India Company to protect their citizens from Native attack left New Amsterdam defenseless. The situation created an opportunity for Director Peter Stuyvesant to seek terms with the British that might improve the safety and security of his citizenry.

The Brits provided protection and religious freedom in New Amsterdam. However, the Brits were ruthless in their conquest of settlements along the Delaware River where settlers were captured and sold into slavery. As an example of terrorist activity, the Mennonite village near Lewes, Delaware was annihilated. In 1673 the Dutch recaptured New Netherland and changed the names of everything British back to Dutch. In 1674 the Dutch could not afford to maintain the colony. Their economy tanked after a decade of warfare and they turned the settlements over to the British. The Brits promptly renamed everything.

Atlantic City NJ

Gen 11: Pieter Wolfertssen von Kouwenhoven (1614-1689)

“Meet me tonight in Atlantic City,” Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band belted the tune out years ago. Imagine owning this beachfront property at one time in your life. This is Atlantic City, New Jersey. Donald Trump owned a piece of it before his casino went belly up. My father’s 7th great grandfather, Pieter owned a chunk of it.

Picture Pieter Wolfertssen cruising down Flatbush Avenue on his Harley heading from his bar in Brooklyn to his digs in Atlantic City. He’s listening to The Boss, Born to Run, on his Beats. Okay it wasn’t possible to do any of that in 1675. But he did own a microbrew and home in the heart of the Financial District (Wall Street) on Manhattan and a large plantation in what would become Atlantic City, long before casinos opened on Boardwalk.

Pieter Wolfertssen’s home was in the neighborhood of the site of The World Trade Center. He was born in 1614 in Amersfoort, Netherlands. We have read all about his father Wolfert and mother Neeltjen. He journeyed with them in 1624 to the New World in the Verhulst expedition. His full name was Pieter Wolfertssen von Kouwenhoven but in his later years he adopted the name Peter Covenhoven. The surname of this family, originally Kouwenhoven means “cold farms.” In earliest New Jersey records the name is given as Corvenhoven, Covenover and Covenhoven. Conover became the most common adaptation of the name at the time of our Revolutionary War.

Pieter married three times: 1) Hester Symons Dawes in 1640, 2) Aeltje Sybrants in 1665 and Josyntee Thomas in 1699. Along the way Pieter also fathered an out of wedlock child and that child is my father’s 6 times great grandmother!

Pieter was first identified in New Amsterdam archives as early as 1633. He was a retailer, engaged in mercantile pursuits with his brother Jacob. Jacob was a miller trafficking in flour from the local windmills. Jacob was a speculator and several of his investments caused Pieter to break from Jacob’s business ventures. He did not want to have his finances tied to Jacob in any way that could come back to bite him. When Jacob’s investments took a turn for the worst, he had to sell a very good stone dwelling and a mill for less than their value. Peter continued mercantile pursuits and stayed out of red ink. He was one of the first Europeans to open a full-fledged, micro-brewery in the colonies.

Traditional European taverns were well established in the colony. Pieter turned a nice profit off the production and sale of beer and ale. Jacob’s fortune turned the corner and his holdings increased. Both he and Pieter were given privileged status as Great Burghers. Pieter held civil positions and was a magistrate between the years 1652 and 1563. His residence and pub located in New Amsterdam was on Pearl Street, near Whitehall,

His tavern was one block to the west of Fraunces Tavern at 54 Pearl Street, five blocks to the south of where the World Trade Center once stood in the heart of the Financial District (Wall Street). Fraunces Tavern hosted clandestine meetings of the Sons of Liberty leading up to the Revolutionary War. The tavern played host to General George Washington and his officers as he bade them good by following the long war for freedom. Fraunces Tavern began as the home of Mayor Stephanus van Cortlandt in 1671. It did not become Fancies Tavern until 1762. It does capture the flavor of Pieter’s Tavern.

His tavern was one block to the west of Fraunces Tavern at 54 Pearl Street, five blocks to the south of where the World Trade Center once stood in the heart of the Financial District (Wall Street). Fraunces Tavern hosted clandestine meetings of the Sons of Liberty leading up to the Revolutionary War. The tavern played host to General George Washington and his officers as he bade them good by following the long war for freedom. Fraunces Tavern began as the home of Mayor Stephanus van Cortlandt in 1671. It did not become Fancies Tavern until 1762. It does capture the flavor of Pieter’s Tavern.

Pieter was also a lieutenant in the military service under General Peter Stuyvesant. On several occasions he was pressed into service against the Native population. I will insert the narration provided by an author at the time:

“In 1663 the Dutch who were settled at Esopus (now Kingston), on the Hudson River, were set upon by a large band of savages. The male portion of the settlers had gone to the field to their accustomed labor, when a number of savages entered the village in a careless manner, sauntering among the inhabitants. Soon after, they sounded their war whoop and began to kill or take captive the women and children. Many of the men were also killed in the field. The total loss of the Dutch was seventy; twenty-five killed and forty-five taken captive. Twelve dwellings, being every house, were destroyed. The mill alone was left.”

“General Stuyvesant ordered Captain Martin Kriger and Lieutenant Covenhoven to retaliate. Their company consisted of two hundred and ten men. of whom forty were friendly Indians, and they marched to Esopus late one afternoon in July. Proceeding four miles, they halted until the moon rose and then marched again, but the country being wild they could not proceed by night. The day being come, they marched forward, felling trees to cross streams, for they had wagons and a cannon. With great difficulty they proceeded twenty-four miles and came within four miles of an Indian fort, to which all the captives had been taken.”

Lieutenant Covenhoven was sent forward with one hundred and sixteen men to surprise the fort, but the Indians had decamped to the mountains, taking their captives with them. Covenhoven continued in hot pursuit and reached an Indian camp, but that too was deserted. The pursuit was given tip after burning up the Indian stores of maize, beans and grain growing. They then marched to another fort, thirty-six miles distant, when a fight took place and several savages were killed.”

Some years later Pieter became involved in lawsuits and several adverse decisions soured his attitude. As he thought these decisions unjust, he made some remarks derogatory of the character of the court, for which he was sentenced to a brief imprisonment and fined. The decisions revolved around family disputes as to who got what part of mom and dad’s estate. For these reasons he left New Amsterdam in disgust.

While Pieter was serving time in prison a census was taken of the population in the colony and recorded. Census takers went door to door gathering information regarding who and how many people lived in each dwelling. Ages, place of birth, occupation were captured for tax purposes and posterity. The records endured over time and reveal a link between the Stille family and von Kouwenhovens that went undetected for centuries. In his absence, Pieter’s home was occupied by our Anders Stille and Annettje Pietersdr von Kouwenhoven.

Valentine’s New York Manual indicates that Pieter retired to his farm of several hundred acres which he owned at Great Egg Harbor, New Jersey, where he spent most of his time. The harbor is still there. Pieter is not.

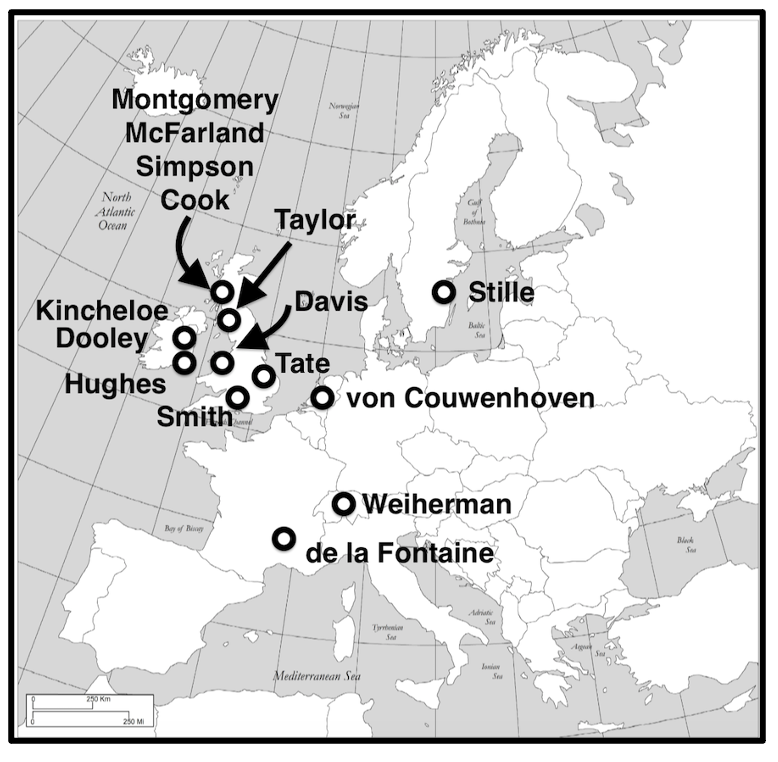

An international community emerges in our family tree with each passing generation: Stilles of Sweden, von Kouwenhovens of Holland, de la Fontaines of France, and next up: The Davis family of Wales.

The Homelands of our Ancestors

A Preface to our Welsh Explorers and Pioneers

I have the Davis family waiting offstage, drinking hard cider and eating Glamorgan sausage with cawl and rarebit. They are rumored to be of Welsh descent and are well-known British explorers whose adventures are recorded in history. Surprisingly, their 16th Century journeys on the Atlantic may have been 4 centuries too late to claim a first in Welsh or family history.

Madoc, also spelled Madog, ab Owain Gwynedd was, according to folklore, a Welsh prince who sailed to America in 1170, over three hundred years before Christopher Columbus’s voyage in 1492. As revealed by his name, he was the son of Owain Gwynedd (aka Owain ap Gruffudd), my father’s 24xGGF. Madoc was my father’s 24x great uncle. The death of Madoc’s heroic father (Owain) led to insurrection among Owain’s twenty plus children. Madoc took to the sea to flee internecine violence at home in Gwynedd (North Wales).

The Madoc legend descended through the ages and attained prominence during the Elizabethan era as monarchs laid claim to North America by virtue of his prior discovery. Madoc’s voyagers, per the growing legend, had intermarried with local Native Americans and their Welsh-speaking descendants lived somewhere in the wilderness. These “Welsh Indians” were credited with the construction of many landmarks throughout the Tennessee and Ohio River valleys. No conclusive archaeological proof of such a man or his voyages has been found, although evidence of ancient loading docks large enough to support ocean going vessels in the 11th century have been found submerged in the North Sea of Wales. Reports of European Native Americans linked to both the Lost Colony of Roanoke and to Madoc’s journeys continue to inspire research.

Madoc had a brother, Iorwerth Drwyndwn ap Owain Gwynedd. Iorwerth was my father’s 23xGGF and the father of Llywelyn the Great ap Iorwerth, my father’s 22xGGF. Within three generations we find two of the iconic rulers of Gwynedd (Wales): Owain and Llywelyn. We also find great uncle Madoc who Welsh folklore credits with establishing Welsh settlements in the New World. Before we scoff at the Welsh for such a story of Madoc’s journey, we should remember that archaeologists have already proven that the Viking’s Leif Erikson was exploring the North American continent a century before Madoc dreamed of life on the high seas.

Look for more about Llywelyn the Great in the chapter dealing with British royalty. For more on Welsh kings from whom we descend check out the following major players in Welsh history:

Rhodri Mawr (820-878 ad) 32xGGF

Anarawd ap Rhodri (d. 916) 31xGGF

Idwal Foel ap Anarawd (d. 942) 31xGGF

Gruffydd ap Cynan (1055-1137) 25xGGF

Gwenllian ferch Gruffydd (1100 and 1136) 25xGreat Aunt, the daughter of Cynan, She was a Welsh princess and warrior and died in battle with two of her sons.

Let’s venture into the next chapter and grapple with more Celtic history via the Davis Clan.

Editor’s note: I should warn you Doc. Captain Davis was complaining about the cawl. It wasn’t “meaty enough.”

Author’s response: Humor him. He has killed people for less.