1638: St. Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh, Scotland

Jenny Geddes sat, perched on her three legged stool on the vast floor of the Presbyterian cathedral. The few pews of the palatial church were occupied by the wealthy aristocrats of the community, a forerunner of the luxury boxes found in today’s great American arenas. Geddes was surrounded by the neurotic sweat of her neighbors and friends, the working class poor of Edinburgh. The peasants squatted on the stone floor or brought their own stools from home. Jenny was fond of her old weather beaten stool. She would proudly point out the smoothy rounded erosion of the wood carved by the firm planting of her butt cheeks day after bloody day, over the years. But, on this day she would surrender her prized perch to the devil himself. On any normal Sunday her mind would wander back and forth between the pulpit in the sanctuary of the grand old cathedral to her stall in the hubbub of the Edinburgh market place, a stones throw to the north. This was not a normal Sunday. Her eyes were riveted on the church notables gathered like a posse in the sanctuary.

When the ruddy woman wasn’t on her feet bartering with a customer on Market Street she would take small breaks and lean her weight into the pine board seat. This summer Sunday morning had a different feel to it and not a good one. Jenny’s fingers gripped the stool beneath her arse . Her arms tensed in anticipation of calamity. Her gullet was filled with the acrid taste of royal bile.

On the previous Friday she had heard enough of the rumors. She could smell the King’s wicked intention. Agitated, her skin crawled with a rash in the early morning hours. She had been sleepless for several nights, but she would be in church on this Sunday as always and in defiance of the words of the Apostle Paul (1st Timothy 2), she would speak her piece if the occasion required.

For several weeks the marketplace in which she toiled was a caldron of speculation. Directives would soon be handed down by King Charles I: Directives that would be implemented by the Bishops of the church with the threat of death an eminent possibility for anyone who did not adhere to the King’s orders. The King’s men would edit the prayer book, alter the altar and change baptismal procedures. Communion would not be the same and church governance would be removed from the local presbytery. Preachers would be defrocked if not carted off to the gallows. Charles I was intent on aligning the churches of the Three Kingdoms (England, Ireland and Scotland) as closely as possible in practice and rule to the Church of England.

“Church of England, be damned!” Jenny growled as she threw down the straw broom that swept the cobbles beneath her feet. “Tis a papal state the King wants to govern. He wants to be nothing less than a protestant Pope. And married to a French whore, Henrietta Marie…”

“Jenny! No! You will be getting yourself killed talking like that,” a customer tried to shush Geddes into silence.

“I am tired of it Maddy. I really am. I am too old for this buggeral. He married a catholic and he winters with the cow in Catholic Spain. He is a closet Catholic. And she is a whore, prancing about on a stage as she does. It isn’t godly. A woman should not appear on stage in a theater. Prynne is right about that. It’s a corruption of God’s will.”

“I heard the new laws make it permissible to dance on the Sabbath,” Maddy whispered the words as if confessing a sin.

“And sports will be allowed as well on the Lord’s Day,” Jenny reminded a growing cadre of malcontents. Pigeons gathering bread crumbs scurried among the litter of the day.

Not one shred of this sat well with the proud Scots who viewed their nation and church as one unit, with a sense of militant solidarity. This was one in a series of conflicts over the century that found the Scot at odds with the Brit, the Protestant at war with the Catholic, the Presbyterian confronting the Anglican. The emotions of the day choked impure thoughts from the Puritan soul.

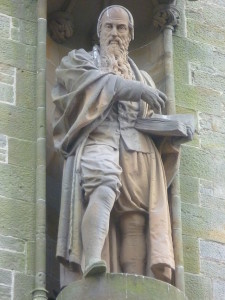

Jenny Geddes was a proud Presbyterian, sitting in a cathedral that was the Mother Church of Presbyterianism. The Catholics had long since been forced from their cathedral and the Reformation in Scotland swept the Catholic, Mary Queen of Scots, from her throne in 1567. The firebrand preacher John Knox (1514-1572), lit up the heavens with sermons demanding piety, reverence for God and the word of the Bible. No man or woman could claim the divine right to rule on earth. No church could put the rule of any one person above the rule of the people. John Knox had been hauled in on the carpet by Queen Mary on several occasions and asked to explain sermons she considered tirades, personal attacks on the Queen. Knox stood his ground each time and eventually deposed the Queen. Many of his followers and peers lost their lives in the bitter wars which ensued. Knox survived. Only God could take his life. No monarch, especially a woman, would conquer the indomitable Knox.

Seventy five years later, in keeping with the protestant spirit of “No Surrender, except to God”, the women of St. Giles would stand their ground in the church that Knox built. During his lifetime, King James I (1566-1625) exerted pressure to bring the Scottish church “so neir as can be” to the English church and to reestablish episcopacy, a policy of top down management which met strong opposition from Presbyterians. In 1617, James made a rare trip to his Scottish home land as King of the Three Kingdoms. He was determined to implement Anglican rituals in the Scot churches. The reformation had rendered these protestant churches unrecognizable to a wannabe Catholic leaning monarch. His bishops forced the Five Articles of Perth through the Scottish General Assembly in 1618; but the Scots resisted. The King’s efforts left the church divided. His son Charles I (1600-1649) would fare no better.

Like his father before him, Charles was intent on moving the churches of his kingdom away from the teachings of John Knox and John Calvin, and in line with the Anglican Church. His bonds with the Catholic nation, Spain, caused concern among protestants of all stripes in Great Britain. His marriage to the Catholic Henrietta Marie of France caused a hemorrhage of support and he found himself at odds with not only the protestants but also members of Parliament. Charles had learned from his father’s failings and brought in several enforcers who would ruthlessly go on the attack to insure the King’s will would be done.

Archbishop Laud imposed the King’s policies and procedures on the people of Scotland. The liturgy would look and sound Catholic. The worship service would look and sound Catholic, minus the Pope. No Pope. Protestant, without the Pope. Laud would be the law. The Laud’s will be done. It was Laud’s belief that Puritanism, not Catholicism, was the chief threat to the rule of Christ in heaven and King Charles on earth.

Only days before the Sunday service that would rock the Scots, the women of the congregation had heard enough to know that changes would be coming at any time. “He’s gone too far, like his father before him, imposing on us as he is,” a woman in the market place complained of King Charles I, as she handed a half pence to Geddes.

“And to his own people. Has he forgotten he is first, a Scot himself?” Geddes responded. Her hand pushed back the sparse hair from the brow of her face.

“He is no Scot, I say,” a third woman shouted over from her stall to the east of Jenny’s. “How could a man turn on his people and our God? And do so with such malice in his heart and violence toward his people!”

“I would not speak so loudly were I you,” Maddy advised. “Laud has his ears about us and he could have you in the Star Chamber accused of heresy and confined to the Tower for your lifetime!”

“And you shall be without your ears, if the Archbishop has his way with you!” Geddes fingers clipped her ears as though they were scissors.

“Cut out your tongue more than likely,” the customer gnashed her gums together and sputtered forth a crumb from a mooring within her few mottled teeth.

“A pox on him and his bloody rule!” Geddes railed, her wrath unfurled. She cleared the fallen crumb from the produce on her counter. “Would that I had the wealth to ever see the Star Chamber!”

“Jenny! Your language. You are a woman of God!” her neighbor to the east was not surprised by Jenny’s anger. She had heard it before, but could not tolerate the language.

“And I am a Scot as well. And God knows my heart is his! But not this King’s, and not this Archbishop!” Geddes eyes quickly darted about the market place, searching for any spy who might report her.

To prosecute those who opposed his reforms, the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, used the two most powerful courts in the land: the Court of High Commission and the Court of Star Chamber. The courts were feared for imposing censorship on those whose religious views conflicted with the King’s and Laud. It was nothing new in Britain or Europe, but it became increasingly unpopular when the punishment was now being inflicted in such degrading manner as it was on the gentlemen of the country. The notorious Star Chamber was located in the King’s Palace at Westminster and reserved for imposing the monarch’s will on any nobility whose attitude needed adjustment.

“I heard they lopped off the ears of William Prynne,” Maddy whispered.

“And for what?” Geddes asked. “The man criticized what goes on in those theaters of London. Sinful plays, not fit for the eyes or ears and Prynne is condemned as the sinner?”

“It isn’t right, is it?” Maddy bit her lip, knowing she was on a dangerous tact. “But it’s not the first. Laud did the same to Bastwick and Burton, now Prynne: All condemned by the Star Chamber to the Tower for life. Branded on their foreheads as sinners and their ears lopped off!”

In 1634, William Prynne, a puritan lawyer had been fined and the top of his ears were indeed cut off. It was punishment for a pamphlet he had authored: Histriomastix. Prynne, a Puritan was critical of theater productions he deemed immoral and unworthy of God. To Prynne’s way of thinking the actresses were prostitutes, and he said so. It was a thoughtless comment in light of the fact that Queen Henrietta Maria was one of those performing on stage behind a mask. In 1637, William Prynne was in trouble again; this time for attacking the bishops.

The puritan minister, Henry Burton (1578-1648) and the physician, John Bastwick (1593-1654) authored essays attacking episcopacy. Burton, Bastwick and Prynne were all three sentenced by the Star Chamber to imprisonment for life and branded on their foreheads with “SL” (seditious libel). Each had their ears severed. Such corporal punishments was widely accepted for a common criminal, the street urchins, but the practice generated outrage among the public when imposed on gentlemen.

“If Laud does it to such men of good standing, wealth and all…. imagine what would be done to each of us?”

“I would rather die first than let Laud see me in that court of his.”

“And he would rather we all die first, rather than waste any of his time on any one of us in his Star Chamber.”

“I think he would turn us all into Catholics if he could.”

“Or fodder for his pigs.”

“It isn’t enough that he wants to change our Liturgy. But the notion that we can engage in sport on the Sabbath!”

“And dance on the Sabbath!”

“It’s heresy! I tell you. Plain and simple. To say this it is permissable to chase through the woods hunting and such on the Sabbath. And dancing the jig on the Lord’s day. It’s folly!”

“It isn’t right missy. It is out right heresy!”

Geddes could stand no longer. She dropped her weight onto the stool for support, wiped her brow and stared into the the cobble streets that led up to St. Giles Cathedral. “I sit now to catch my breath. But God as my witness, we shall not sit still this Sunday should the Bishops think they can impose Laud’s will on St. Giles. We must stand up to this, this heresy. And that is what it is. Laud charges our preachers with heresy. Charges us as heretics? Brands our foreheads? Causes our preachers to disappear. No, he is the heretic. The agent of the devil himself. And the King has a fight on his hands if he thinks he can just dance into Edinburgh and do this to his own people.”

“What shall we do Jenny?” the women gathered closely about her stall and whispered in tones that suggested conspiracy.

…..

Jenny Geddes clutched her footstool knowing that something was amiss this Sunday morning. The big shots were sharing the altar today. James Hannay, Dean of Edinburg and Dr. Lindsay, Bishop, were both seated behind Patrick Henderson as he performed his usual duties: reciting the prayers of the congregation. To the surprise of everyone, Henderson fumbled with the lectern and stared into the audience. Perspiration formed on his furrowed brow. “I bid you adieu good people; for I think this is the last time of my reading prayers in this place.” The Congregation murmured collectively. A few horrified gasps signified that Henderson must have good reason to be leaving his post. He was a devout man of God. No sooner had Henderson stepped down to leave the cathedral than James Hannay, Dean of Edinburgh, appeared in his place. Without hesitation and in a loud voice, seeking to take command of the congregation Hannay began to read the service in the manner proscribed by King Charles I and Archbishop Laud.

John Knox had worked diligently to eliminate or revise the Book of Common Prayer as it had been imposed by the Anglican Bishops over the years prior to 1560. Laud scrapped the work of Knox. Hannay was reading from the King’s Anglican version. The words burned Geddes ears. She was not alone. A number of women began clapping their hands loudly and defiantly, drowning out Hannay’s recitation. The wailing of voices soon followed and hideous exclamations. There was a great confusion in the church, a result of a planned spontaneity, which the Bishop, Dr. Lindsay, hoped to subdue with his reminder to the congregation: “We are in God’s house!” It was to no avail.

The affront was too much to Jenny Geddes. She stood up, grabbed her stool, and hurled it at the Bishop’s head. Vile language filled her throat as she cursed the man: “The devil cause you colic in the stomach, false thief! Dare you speak the Mass in my ear?”

Had it not been for the magistrates of Edinburgh, the congregation probably would have stoned Hannay and Lindsay to death on the spot. The furor continued into the streets of Edinburgh as the crowd followed the magistrates protecting Lindsay on his way to a safe house. The crowd became unruly, knocking at doors, drawing others out to riot and throwing stones through windows. “Pope, Pope, Antichrist, pull him down!” the crowd shouted. The furious Geddes and her fellow parishioners of St. Giles ushered in a dreadful and destructive civil war, The Bishops War.

Laud thought that, by 1638, he had disfigured enough faces and severed enough ears to impose discipline. In fact, he merely created a backlash amongst the gentry. During the ensuing months, the protest grew into a hubbub of petitions and supplications denouncing Laud’s prayer book and criticising the power of the bishops (episcopacy). Led by the lords Loudoun, Rothes, Balmerino and Lindsay, the once unruly mob organized four committees elected to represent the nobility, gentry, burgesses and clergy, and a fifth committee to act as an executive body. The clergyman Alexander Henderson and the lawyer Archibald Johnston of Wariston were given the task of drawing up a National Covenant to unite the supplicants and to clarify their aims. Based upon the Confession of Faith signed by James VI in 1581, the Covenant called for adherence to doctrines already enshrined by Acts of Parliament and for a rejection of untried “innovations” in religion. Although it emphasized Scotland’s loyalty to the King, the Covenant also implied that any moves towards Roman Catholicism would not be tolerated.

In February 1638, at a ceremony in Greyfriars Kirk in Edinburgh, large numbers of Scottish noblemen, gentry, clergy and burgesses signed the Covenant, committing themselves under God to preserving the purity of the Kirk. Copies were distributed throughout Scotland for signing on a wave of popular support. Those who hesitated were often intimidated into signing and clergymen who opposed it were deposed. By the end of May 1638, the only areas of Scotland where the Covenant had not been widely accepted were the remote western highlands and the counties of Aberdeen and Banff, where resistance to it was led by the Royalist George Gordon, Marquis of Huntly. With all the effort, over 300,000 signatures had been gathered.

Jenny Geddes exemplified the spirit of the Reformation movement, the Presbyterian commitment to the principles of John Knox and Calvin and a willingness to fight to the death for the right to worship. The Three Kingdoms were under siege and at war in a nation that had been torn by centuries of war.