When Jenny Geddes (Chapter 1) tossed her chair at the Bishop in St. Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh, Scotland she had no idea she was firing what could be called a first shot in the war against King Charles I and Archbishop Laud. Plenty of martyrs had fired their own verbal shots over the years. And, since martydom requires that you pay with your life many men and women had paid a steep price. I suspect that Jenny didn’t even lose the stool she tossed. I am willing to bet a subscription to the Economist that the gutsy shop keeper and thrifty Scot retrieved the chair before she pursued the Bishop through the streets of the market place. I am equally certain that she also made the 6 O’clock news and was trending on Kilt-book for at least a week. When the Greyfriars Kirk (Church of Scotland) met in Edinburgh in February of 1638 to sign the historical Covenant, they committed to a war that would tear the British kingdom apart, pit Puritan against Anglican, give rise to an out migration of citizens seeking new lives all over the globe and change the course of British family histories for centuries to come. This script continues below… Read on!

Do you remember the scene in the 1970s movie, Network? Oscar award winner Peter Finch (cast as nightly news reporter Howard Beale) roars his disgust: “I am mad as hell and I am not going to take it any more!” The Scots, with Covenant in hand, were taking that kind of a firm and angry stand against a Scotsman, the King of England, King Chuck the First. While the Covenant proclaimed their allegiance to the King they did throw in a qualifier: the King was to cease and desist, and Laud was to no longer trifle with their Presbyterian ways.

King Charles considered the men in kilts to be a bit insubordinate and launched a weak attack in the Scottish highlands, only to be knocked back into the British lowlands. A treaty called the event to a close and the King went into the off season looking for a blockbuster deal that would improve his military play book. But, the attack on Scotland didn’t play well in Parliament and the man on the street in London saw it as another example of the King’s failure as a human being. When the new season opened the King launched Attack on Scotland, Two, the Sequel. Sportscasters everywhere were stunned. Just when you didn’t think the Chicago Cubs could get any worse, they were worse than before. The British army not only got knocked on a royal keester but this time the Scots chased the Brits south across the River Esk into England and seized the Tyneside community of Newcastle. The King agreed to peace once more. The Scots returned Newcastle to the Brits and may have complained about the poor quality of the distilleries. It would take centuries, but the Brits came up with a recipe for a brown ale (Newcastle) that would make some Scots accept a beverage other than their beloved whisky.

The Scots had no love or use for the King, or his word at this point. A treaty apparently meant nothing to the King. So the Scots went on the offensive in the halls of Parliament and out maneuvered him on his home court. The Covenanters, as they preferred to be called, allied themselves with protestant sympathizers in the British Parliament. The struggle between Presbyterians and the Anglican Church (captained by King Charles I), now became a battle between the Covenanters, and their allies in Parliament vs the King and Cavaliers. And no, I am not talking about King James (Lebron) and the Cleveland Cavaliers.

It had to be a bit perplexing to the Scots. Charles I was Scot by birth but moved to London in 1605. He hadn’t really returned to the north country during that span of time. His father James, was King of Scotland before he overindulged and took on the role of King of England as well. Tension had been building for one century on the island and in the whole of Europe. Push had now come to shove in the highlands. Yoga exercise and caber tossing would no longer relieve the stress. The first of the Separatists (Pilgrims) had already fled England for the new world. The Plymouth Plantation (or Colony), though struggling from infancy to adolescence (1620 to 1635), was a success and demonstrated that life could be maintained in New England. Pamphlets, created by Edward Winslow and William Bradford,circulated in England and announced the Grand Opening: ‘Come to Plymouth! We are now open for business!’

British Puritans, French Huguenots, Separatists of all kinds now had options. It was as good as going into the grocery story and choosing between Weetabix and Oatmeal. Holland had been the only safe haven. Holland was only a short hop away and attracted many who were looking for a fresh start in life. Bumper stickers were everywhere in England: “Escape to Amsterdam!” But that short hop across the channel was just as easily bridged by the King’s men as it was by a frustrated, freedom seeking Presbyterian or Puritan. We have witnessed the narrow escape from Leiden made by ‘the Brewster’ and his posse, including the Winslows. We have met the first Pilgrims in Plymouth as well as the first wave of Brits who settled into Boston and the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Several colonies were growing in a new world the Brits called ‘Virginia’ and more would evolve. We have witnessed the rise of several iconic figures in early American history. John Cotton played a leading role as the edgy preacher who could ride a fence like few politicians in the new world. Governor John Winthrop, cast as an early version of Lyndon Baines Johnson, knew how to push his will into place and his words into publication in Boston. And it wasn’t really thought of as Virginia any more. Terms like Massachusetts Bay Colony and Plimouth Colony were taking on meaning in terms of civics and geography.

Capturing center stage for fully two years (1936-38) was the irrepressible and undisputed champion of the cathedral set: Ann Hutchinson. Hutchinson was a no holds barred Bible brawler who could knock down any argument with her quick mind, confident psyche and familiarity with The Word. Watching Ann’s daily trial and tribulations were a number of our ancestors, some of whom were lesser known preachers, deacons and elders. They followed events in Boston from as far away as London, Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Sussex and Amsterdam. Hutchinson’s fate was of great importance to those watching from Europe. What would these Puritans, who left England seeking to be tolerated, do with a person they couldn’t tolerate? Would she die in prison as so many had died in the Tower of London? Would she die on the hanging tree? Would John Winthrop have her dragged through the streets, beheaded, drawn and quartered and mutilated beyond recognition? If so, it wouldn’t bode well for those thinking New England offered a great escape.

In previous chapters I brought the characters of Ann Hutchinson, John Davenport and John Wheelright onto to the stage of this reality show. I will now introduce a supporting cast of characters whose lives are intertwined with the headline stars of the 1630’s. As is so often true in life, intertwining can lead to marriage and often leads to offspring. And so it is that the starts of MBC (Massachusetts Bay Colony) in the 1630s also become lodged in our family tree. Hutchinson, Davenport and Wheelright take their place in our family tree via marriages, along with the cast of characters about to take the stage. They were all just people trying to eke out a living, searching for a connection to the God they believed in. And they all enter the theater production, Life in New England, as part of the Great Migration.

Their cellular service in England had not been the best. Our ancestors were getting one bar and needed five bars. The only thing the government could give them was life behind bars. It was as if they were living in North Korea with Seth Rogen as emperor. There was a way to worship God and connect with God. They knew that. They knew communication was a two way street. They believed sending and receiving messages with God worked best if one understood what God needed from mankind. They were seeking a personal relationship with God. They wanted to cut out the middle man in the communication process. They didn’t need a Pope or Cardinal or Archbishop or even a priest to tell them ’this is how you do it!’ They didn’t need a King to interpret the Bible for them any more or Laud telling them how to live. They didn’t need a priest to intercede for them. They could pray directly to God and feel the presence of their Lord. Parishioners were well versed in the Bible and possessed Cambridge or Oxford trained preachers. They were literate followers of the Word. The printing press put God’s word right there in their grubby, gnarled hands or white collar mittens. They knew how to read. They knew how to worship. They knew how to talk to God and feel the presence of God.

Literacy created all kinds of disturbing issues for the monarchy and for the church elders. And yes, they were grateful to King James I for that version of the Bible he stamped his name on. It was cool that the word of God was written in a language they could understand and that it was readily available. A commoner capable of reading the Bible could also create new truths, discover old lies and unveil the hypocrisy found in church dogma, doctrine and dictates. King’s faced the same dilemma in their secular rule of the land. King Charles I believed firmly in the Divine Right of Kings and decided that he could rule the three Kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, without a Parliament. That kind of thinking blew common folk like Jenny Geddes out of the water. It also caused guys like Oliver Cromwell to take up the sword and raise an army of Roundheads ready for war.

As the event in Massachusetts known as the Antinomian Trial hammered down to a conclusion, the bookies in London were laying odds that the court would sentence Anne Hutchinson to death. But alors! Or is it ‘Alas!’ ? The Puritans in the Bay Colony allowed Hutchinson to live. Game on! There was plenty of land on that new continent for folks to spread out and worship and live unencumbered by centuries of the same old, same old. The middle ages had to come to an end sooner or later. It appeared to those watching in Europe that the Puritans in the Bay Colony were sending a message something like this:

We all have our differences of opinion here in the Bay Colony. The guys in Boston are nonconforming Puritans and those of us out here in the burbs are more conformist. And we agree to disagree. We won’t necessarily hang you if we find a difference we don’t like. Not just yet anyway. We will invent the witch trials at a later date and those of you claim to be Quakers may be a separate issue. So, come on over and join us. There are ships leaving various ports in Europe on an irregular basis. Find a ship and join us! Or go on our website: Find-a-Pew.com We’ll match your religious beliefs with a colony and help you settle in. And for God’s sake, please bring your wallet. We need a cash flow and a cash cow would help too. Oh! and here’s an App that will help you locate a village that serves up the kind of food you like.

Our man, the Reverend Robert Peck (Whittington ggf) was already hunkered over a good porridge in Hingham, Mass, when Ann Hutchinson (Whittington gga) was on the road to freedom in Rhode Island in August of 1638. Born in 1580 Peck had grown old in Hingham, Norfolk, England and had hoped to live out his years there, watching the grandchildren, tending to his congregation and reading an occasional Shakespearean Play (if they were fit for Christian consumption). The Tempest, Stefano cast as ancestor Stephen Hopkins, would have been a pertinent choice for one who had just crossed the ocean. The boy from Beccles (Peck) had become a man of the cloth in Norfolk, England, a vicar of Hingham at age 25. Time flies when you are fleeing the wrath of the King and raising a family.

Robert Peck’s Puritanical thinking influenced parishioners for three decades in England and he went from upstart to old fart in his march against the catholic views of the established Anglican Church. In 1633 several of his parish families left for America from Yarmouth on the good ship ‘Elizabethan Bonaventure’. Peter Hobart, (Whittington ggu), a younger version of Peck, and Peck’s assistant pastor in Norfolk, led the first of the congregation’s families to a new settlement in the Bay Colony. They settled into a spot on the bay called Bare Cove. As had become practice, they eventually purchased the land from the Wampanoag sachem (chief) Wompatuck in 1655.

The Brits typically hunkered down first and ‘purchased’ as an after thought. The need to purchase was usually motivated by fear. What if someone else comes along and wants this property? The Dutch, for example, were just down the shore line investing in beach front property and building an empire as well. And those pesky Swedes on the Jersey shore, south of Manhattan! What if they show up looking for a place to make lutefisk and build a sauna? And of course, there were other Brits coming into play as well. Better be able to show a deed when they start eyeballing what we have here. The Natives didn’t understand land ownership. They had not yet developed the concept of realtors, mortgage banks and foreclosure. The great sachem could only smile as these white guys gave him gifts. In his mind it was Christmas, the land was not his to give away. In fact, he would be back the next day on the same land with the same hunting party of best buds, looking for lunch meat, maybe a cod fish sandwich, and a good place to catch a nap.

In 1635 a second group of Peck’s congregation sold their belongings in Norfolk, England and traveled the ocean to Bare Cove. Peck’s relationship with Archbishop Laud and the Anglican Church had deteriorated and the Reverend was in trouble. He was called before a consistory court in Norwich and charged with “contumacious disobedience to the orders and ceremonies of the church.” The charges were similar to those that Anne Hutchinson faced in Boston. Peck had been holding prayer meetings in private homes in violation of state laws. He was spouting out beliefs about baptism and communion that the church held as contemptible heresy. He was excommunicated and without a job. In 1638 Robert and his family (wife Anne Lawrence and children: Joseph, Robert, Thomas and Ann) as well as two servants, sailed for America in the ‘Diligent of Ipswich.’ The Pecks joined the growing enclave at Bare Cove which was now going by the name Hingham. Preacher Hobart felt that the name Bare Cove suggested there might be a nude beach and this appalled some of his Puritanical citizens.

Many New England family names are represented in Peck’s entourage: Buck, Chamberlain, Cooper, Cushing, Foulsham, Gates, James, Ripley, Tufts and yet another Peck: Robert’s brother Joseph Peck (ggu). Joseph’s wife and four children joined the exodus from England. Joseph Peck must have given up a great amount of wealth when he fled from Norfolk. He brought two male servants and three maids. It would take a large home to accommodate 7 adults and 4 children. Robert became a teacher at the church and assisted its first minister, Peter Hobart, and Peck’s original assistant in England. Hobart would marry into our ancestral tree as we move through the ages. His first wife, Elizabeth Ibrook passes away somewhere around 1638. Even though Peter kept a journal recording births, baptisms and deaths, he did not record the passing of his first wife. New England’s premier Puritan preacher, politician and author, Cotton Mather, noted in his records that Peter Hobart preached in Hingham without benefit of his wife’s consort. She apparently remained in Charlestown, nearer Boston. The fact that she was kept busy delivering children and that several of those children succumbed to death within their first year may have provided reason for her to stay in Charlestown. At any rate Hobart’s second wife is Rebecca Peck, daughter of great uncle Joseph.

Our great grandfather Robert, his brother (our uncle) Joseph and Joseph’s son-in-law Peter Hobart (who interned under Preacher Robert back in England) provide an interesting slice of American history for our family. Together, they launched the Old Ship Meeting House on property donated by another Peck brother (and great uncle) Joshua. It is the oldest surviving church, still in use as a church. Of course the Puritans called the buildings ‘Meeting Houses’, finding even the reference to ‘church’ as too Catholic to be comfortable. As one old colonial reported, “the only difference between a church and the tavern was the presence of the preacher.” Preacher Hobart served the community for fifty years despite his knack for irritating the Puritan establishment hierarchy. Hobart was called to task on several occasions when he opened his doors to Christians who were not Puritans and baptized children whose parents were Anglican. He was ahead of his time when it comes to being ecumenical. His ideas were a forerunner of the Universalist Church to come along later.

The Old Ship Meeting House is home to another famous name in American history. The pastor who steps in upon Peter’s death is the Reverend John Norton. He is the great grandfather of Abigail Adams whose term in our nation’s White House was shared with another great American, John Adams. If you check the records she had a son who also became President, John Quincy Adams. While Abigail was the daughter of Reverend William Smith (no relation), her mother was a Quincy and the records of Hingham reveal a number of citizens with the variations on the spelling of Quincy. It should also be noted that Hobart was spelled in a variety of manners including; Hubbard, Hobird and Hubberd.

Robert Peck would remain on this side of the Ocean until 1641 when his church back in Hingham, Norfolk petitioned for his return to England. In 1641 Oliver Cromwell and the Roundheads were fully engaged in a Civil War in England that would keep the Archbishop Laud at bay and the King busy trying to control the rascal Scots and parliamentarians who wanted to end his Divine Right to live, let alone his divine right to be a King. Laud had been captured and confined to jail in 1640. Cromwell was a hero among Old Testament Puritans who liked the idea of an “eye for an eye.” There was nothing wrong with throwing a few Christians to the lions, as long as they aren’t our Christians. Peck deemed it safe to go home and left the colonies in 1641. He was serving as rector in Hingham, England in 1645 and died in 1656. His term here was short but saved his life. It was the rise of Cromwell and the Puritan Roundhead forces that ended the Great Migration of the 1630’s. The population in New England had gone from 4,000 in 1630 to 50,000 in 1640. The trend would now, however, reverse. Puritans in the colonies who missed England would begin a long trek home to loved ones, sorely missed.

Let’s throw Edward Winslow (a Wetherell/Whittington ggu) our Pilgrim ancestor in Plymouth, MA back into this mix. He was a world traveler who made frequent trips to England and Wales among many other destinations. Winslow was a man of many hats. He reveled in his role as a Public Relations and Marketing guru for the Plymouth Colony. He was all about growing the new world colonies. Just when I thought I could put a wrap on the story of Edward Winslow, Mayflower Pilgrim, I found him leaping off the pages. He spreads himself ever wider, like a bald eagle protecting his kill. Let the intertwining continue. And keep in mind: When you only have 50,000 citizens (men, women and children) living in New England it really isn’t all that unusual that we find famous names in history in our family tree, and that we find close knit families celebrating multiple marriages down the lane, from one another.

The Whittington family tree has been historically documented as descending from the British Plantagenet monarchy and William the Conqueror. The colonist linking the American tree to Britain royalty has been documented as Obadiah Bruehn. In compiling Obadiah’s story I found a wealth of information regarding his extended family and circle of friends and business partnerships. In recent research I traced historical records from the 19th century that were a revelation as to how Obadiah got here. I did not expect to find an ancestor from one part of our family tree (Winslow) interacting with a character from another part of the tree (Bruehn), but there they were. Small world, especially then. The following passage in Babson’s “History of Gloucester, Massachusetts” opened a few doors in understanding the life and journey of Obadiah Bruehn:

“Gov. Edward Winslow, Pilgrim founder of Marshfield, often visited England; he induced several Welsh gentlemen of respectability to emigrate to America, amongst whom came the Rev. Richard Blynman, in 1642, he was the first pastor of Marshfield. Some dissensions taking place, Mr. Blynman and the Welshmen removed to Cape Anne in less than a year. In 1648 Blynman went to New London, in Connecticut, of which place he was the pastor ten years. In 1658 he was at New Haven, and soon after returned to England, after having received in 1650 an invitation to settle at Newfoundland. He died at the city of Bristol, England.” [1]

Richard Blynman is not a relative. It is the reference to the “Welsh gentlemen” that caught my eye. The Blynman party originated from Monmouthshire, Wales in 1640 and is well documented. Many of the members of Rev. Mr. Blynman’s party, but not all, were members of his church, at Chepstow, Monmouthshire, Wales before the King ejected Blynman from the ministry. The several other passengers , the “Welsh gentlemen of respectability” recruited by Edward Winslow, included our own Obadiah Bruehn. Of course, we share him with an arena full of people these days. Historians believe the Blynman party first arrived in Plymouth, Plymouth Colony. Records from the Plymouth Court, the governing body, regarding members of the Blynman party read as follows:

“At a General Court held in Plymouth, (Mass.,) Mr. Blynman, Mr. Heugh Prychard, Mr. Obadiah Breuhn, John Sadler. Heugh Cauken, and Walter Tibbott were propounded to be made free the next Court.”[1]

In today’s English this means these six men were declared freemen, entitling them to own land, participate in the economy, vote and hold office. It was a good thing. But, they didn’t stay in Plymouth village long enough to add to the decor. Both Bruehn and Cauken are great grandparents in the Whittington line. I was equally stunned to find Cauken traveling with Obadiah and Winslow. Bruehn slipped away from the Blynman group long enough to travel north to Portsmouth, New Hampshire where he held a patent for land on a Piscataqua river property. He unloaded the deed and headed back to the Plymouth Colony. This commitment would thrust Bruehn into a leadership role with this traveling community for a lifetime. The path they would take through New England would bring them into contact with various ancestors and onto the front stage of Scene Two: The Birth of a Nation. It was cool stuff and they sensed the importance of their mission.

In 1636, Edward Winslow and wife Susanna (White) Winslow had moved their family from their initial quarters on the northwest corner of Street and Highway in Plymouth to a new address in Marshfield. That is correct. The Pilgrims were not into anything that smacked of flamboyance. There were two roads in Plymouth: they called one ’street’ and the other ‘highway’. Where did the highway go? And how could it go anywhere if they just moved off the ship and into town? Well, the Natives were there first and had developed an elaborate road system over a period of 10,000 years, give or take 5,000 years.

Edward’s younger brother Kenelm moved into the colony around 1626 and had a prosperous farm on the opposite shore of the Green River. Kenelm was developing into a world class joiner, a man whose furniture was well crafted and is considered a collector’s item today. From his front porch he could watch his young nephew, Peregrin (Winslow) White run his horse from his home to his mother’s, Susanna (White) Winslow. Peregrin, born on the Mayflower while still at sea, was becoming a young man in the mid 1630’s.

Edward Winslow was developing various business opportunities and partnerships. Winslow had established a friendship with native sachem (chief) Massasoit, whose people were trading with the colonists. In January 1629 he lined up a new patent for land at Kennebec, Maine which provided for a fishing and trading post at Pentagoet and a fortified trading post at Cushnoc. This helped Plymouth expand her economy and the reach of her influence in New England. In this effort Winslow was partnered with John Alden and John Howland and in competition with Mayflower passenger: Isaac Allerton. Allerton elected to jump into the marketplace in competition with his neighbors. The Winslows, Aldens, Howlands and Allerton were all Mayflower passengers found in our ancestral tree.

Keep in mind that a person couldn’t simply move into a territory and assume possession of the land or access to the resources. The King owned all lands and resources and they could only be distributed by patent (deed). Squatting was an offense that brought consequence. Winslow’s respect for the Natives was obvious in his business dealings with them. A Pilgrim had been executed for murdering a Native. Pilgrims were punished if their trades with Natives were unethical. Winslow’s integrity was recognized by Natives and his efforts paid off with fifty years of a peaceful working relationship with the tribes. That would change upon his departure.

Winslow was also making frequent trips to England on behalf of the colony. It was on one of those trips that he had approached Obadiah Bruehn and his ‘respectable’ Welsh countrymen. Whether Bruehn himself was Welsh could be subject to debate. His home in Cheshire, England was in that part of the Welsh marches that was some times England, some times Wales. Castles in the area, including the Whittington estate, had been handed back and forth through the centuries. They changed hands as easily as a white elephant at a family reunion gift exchange.

As ships arrived during the 1620’s and a greater number of residents moved in, the population fanned out from Plymouth to the north and east, in the direction of what would become Boston. John Alden was founding a community at Duxbury. Not one to sit still in a house full of children, Winslow explored the New England coast with his heart set on property development and trade possibilities. In 1632, he made an exploratory tour up the Connecticut River with colonization in mind. It has been suggested that he landed and selected the settlement which became Windsor.[21] His exploration of the Connecticut shoreline becomes critically important in the development of our collective family histories including Separatists, Puritans, Swedes, Dutch and any atheist pretending to have God on their side.

Now that Winslow had enticed the Blynman party to the west side of the Atlantic, he would draw them to his community of Marshfield. The village was previously called Green’s Harbor after a fisherman,William Green, who prospered there and developed the port facility. Marshfield was incorporated March 1, 1642. Over the next several centuries it would be a Winslow family community and reflect the political and religious values that characterized Edward Winslow: a protestant businessman with strong ties to the economy of London. Marshfield connections to London would remain firm and set it apart from much of New England through some very turbulent years.

Richard Blynman was a humble preacher traveling in the company of farmers and merchants who appeared to have magnetic chips planted in their brains. They were drawn by a Utopian view of the world that allowed them to believe that a community of people with a common core of spiritual beliefs could, in fact, establish a municipality and nation in which they could govern themselves and make decisions based on their commonly held beliefs about God, the Christ and the Bible. That magnetic chip, or whatever it was that drove them onward, would cause them to pack up their homes and move several times before each died in a different location. Their tombstones would be scattered from Marshfield, to Gloucester, to New London and Newark, NJ. Some would return home to England and be buried in the yard of their childhood church. Much of their personal and communal journey was tied to the success and failure, the rise and fall of Oliver Cromwell, in England. This would prove true for the Cavaliers in our family tree as well, the Whittingtons, Littletons, Davis and Smith families.

While Blynman is credited with starting the first church in Marshfield, his stay there was short lived, perhaps less than a year. His reasons for leaving are not clear. It is conceivable that significant differences arose between the Blynman congregation and the Pilgrims. Speculation suggests that ‘speculation’ may have been the driving force. Winslow was developing fishing and trading outposts along the New England coastline. Gloucester was but one of several villages and posts that he was developing. Did Winslow convince the Welsh party to help him turn Gloucester into the thriving fishing port that it has become today? It certainly wasn’t headed that way at the time.

Or was politics involved? Upon his departure as village pastor, Blynman was replaced by another of our distant cousins, the Rev. Edward Bulkeley (Whittington line), son of the first minister of Concord, Mass. The Bulkeley family had close ties to Governor John Winthrop (a shirt tail relation in the Wetherell line) in Boston and had earned their stripes as Winthrop’s henchmen when the father, Peter Bulkelely, went after Anne Hutchinson with a vengeance and facilitated her exit from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Perhaps Blynman was being chased out of Marshfield for political reasons, creating an opportunity for Edward Bulkeley to acquire his first job as a vicar. Whatever the reason, Blynman and his followers were heading north to Gloucester in 1641. It was a whirlwind tour of New England for Obadiah Bruehn. Within two years he had visited Plymouth, Portsmouth, Marshfield and now Gloucester. He would have a few more stops along the way before he headed off to the pearly gates of heaven.

On March 2, 1642, With Mr. Endicott and Mr. Downing presiding, the records of the Gloucester Council indicate eight of the

“Welshmen were chosen to manage the prudential affairs: Wm. Stevens, Win. Addis, Mr. Haywood, Mr. Sadler, Mr. Bruen, Mr. Fryer, Mr. Norton and Walter Tybott.”

Haywood and Stevens are family names that show up early in our family tree. This record indicates that the Welshmen were recognized as freemen in Gloucester and that they were coming in as newcomers and immediately assuming the role of managers of “prudential affairs.” This is to say that they were charged with the conduct of all miscellaneous business related to the municipal operations of Gloucester. These farmers and mechanics were charged with becoming the founders of Gloucester, which was then little more than a fishing station and an unfavorable place for fishing at that. So unfavorable, in fact, that Pilgrims who first tried to open a harbor there in 1623, gave up in 1626. The harbor was treacherous, the fish were comparatively few and the opportunities far better elsewhere along the coast.

Nevertheless, Blynman and company would do their due diligence and try to make a go of it in Gloucester. The Rocky Neck peninsula and island was largely a rocky outcropping that looked great in a Winslow Homer landscape painting, but was hell to plow without dynamite. What soil that could be found was rock filled and a bear to claw. It could have been used as a good tax write off; but the wealthy had not yet created such a tax loophole or a federal government that would condone the practice. While there was a will to live, there was little to farm.

And the fishing? The factors that forced the closure of Gloucester in 1626 had not changed. Access to the ocean was treacherous on a good day. Blynman stayed long enough to have a canal and a bridge named after him. The Reverend supervised the cutting of the first canal at the harbor end of the Annisquam River. The canal provided a safer passage home for those boats that fished north of Gloucester. The first bridge, the Blynman or “Cut Bridge” was built over the canal centuries later. One present day critic writes that “it is the source of long delays to summertime motorists who must wait for boat traffic to pass under the draw bridge.” The price of progress. And the wait time for that bridge to lower isn’t nearly as long as one of Blynman’s sermons.

While Blynman had built the first church in Marshfield, he did not build the first church at Gloucester. A primitive church had already been established in 1633. A “Master” Rashley was the pastor preceding Blynman. In 1652 Rashley is identified as the minister at Bishop-Stoke, in England. I mention this as part of that pattern: Chased from England by King Charles I in the 1620’s and 30’s, Puritans return home with the rise of Cromwell. Blynman would eventually return to England in 1654, as would Robert Peck. Blynman’s time in Gloucester is cut short and this time the evidence is clear: He was unpopular. That he was harassed is evident in a passage from Babson’s account (page 191) :

“Unhappy dissensions drove Mr. Blynman from the scene of his first ministry in ‘New England; and the ill-treatment he received from some of his people here may have hastened, if it did not induce, his departure from the town. His church was defamed; and he himself was scoffingly spoken of for what he had formerly delivered in the way of the ministry. But he appears to have worked undisturbed in the other fields of his labor, and to have lived in peaceful and harmonious relations with all. He was greeted with the loving salutations of eminent men; and a contemporary writer, (Johnson, in his ” Wonder-working Providence”) described him as a man ‘of a sweet, humble, heavenly carriage,’ who labored much against the errors of the times.” — [Babson’s ” History of Gloucester, Mass.,” page 93]

Rejected in Gloucester and apparently humiliated, Blynman moved on to New London, Connecticut in 1650. Babson notes that Mr. Blynman was accompanied by “several Welsh gentlemen of good note.” They should have organized a band and migrated around the county fair circuit while they were at it. “Arriving in New London, Connecticut, from Gloucester, Massachusetts were Christopher and James Avery, Wm. Addis, Obadiah Bruen, Hugh Calkin, John Coit senior, Wm. Hough, Wm. Kenie, Andrew Lester, Wm. Meades, Ralph Parker, and Wm. Wellman.” This Cape Ann tour group that left Gloucester for New London consisted of about twenty families in all.

“It is probable that Mr. Blynman’s wife Mary and Dorothy the wife of Thomas Parker, were sisters : so Parker was very likely another of the party. In March, 1651, the principal body of these eastern emigrants arrived at New London, among them John Coit Jr, Thomas Jones, Edmund Marshall and his son John, Wm. Hough, Wm. Meades, and James Morgan. With them also came Robert Allyn, from Salem and Philip Tabor, from Martha’s Vineyard (who very likely did not come with Blynman). The younger Coit, the two Marshalls, and Thomas Jones, after a short residence in New London, returned to Gloucester. Several other persons appeared in New London at about the same time (dates unknown and places of origin unknown) : Matthew Beckwith, John, Samuel, and Thomas Beebe, Peter Collins, George Harwood, Richard Pool and John Parker.”

I know, I just littered the paragraph with a lot of names without faces. It’s a bit like looking at the roster of the Chicago Cubs and wondering why you would be interested in any of them. The groups that traveled in a pack were often intermarried to the point where they were blood relatives sharing DNA, household appliances and probably a toothbrush. There are several family names in this Blynman group that surface in New London for the first time including the Parkers. Allens, Morgans and Harwoods also show up in the family trees as cousins, in laws and aunts and uncles. We are going to leave this Blynman group stranded at the doorstep in New London in 1650 and head back to Plymouth Colony in 1630. There are a few more players to add to this mix, people who contributed to the birth and expansion of our nation.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

The Reverend William Wetherell (an uncle in both the Smith and Wetherell tree) came to the Plymouth Colony on the ship Hercules, sailing from Maidstone, Kent, England in March of 1634. He arrived with his wife Mary (Fisher) and a family of three children: Samuel, John and Daniel (ages 6 thru 8). The family also arrived with one servant: Anne Richards. The Reverend’s biography is extensive. The title in which the bio is found is extensive in itself: The History and Genealogy of the Witherell/Wetherell/Witherill Family of New England. Again, this begs the question: Why do people have to keep changing the spelling of their surname? Are they running from the law, a paternity suit or a bad debt? Our great grandfather William Wetherell is also identified in this collection as are all of the descendants. It is a thorough collection of biographies. The emphasis in this chapter on preachers will cause me to focus on Great Uncle Reverend William. We will come back to Grandfather William, the soldier and wilderness farmer, in the near future.

The Reverend William was born about 1600 in England and married Mary, who was born around 1604. She was a Boughton girl, and married the Reverend on March 26, 1627 in St. Mildred’s, Canterbury, England. She was the daughter of Thomas Fisher and Joan Lake. The Reverend’s ancestors hailed originally from Wetheral, England, a village that spills into Scotland on a rainy day. Wetherell is yet another family name that is found with letters rearranged in a variety of ways, but all point to the same roots in Wetheral, England. The Reverend William was another of our Puritan preachers whose adherence to beliefs and practices contrary to the Church of England place him in harm’s way. In other words, his license to preach was marked for termination by Archbishop Laud. A Cambridge graduate (MA in 1627), he was identified on Cambridge college roster as a kid from York who took his Masters and taught school at Maidstone, County Kent.

In 1634 Wetherell received a cease and desist order from Archbishop Laud. Basically the citation carried the same no nonsense message every other preacher had been receiving: ‘Stop _________ or come see me in the Star Chamber and we’ll arrange for a speedy trial and quick consequence.’ In this case Laud filled in the blank with the request that Wetherell stop “teaching the catechism of William Perkins and stop following the order of the Sabbatarian Thomas Wilson”, who was considered ‘too Presbyterian in polity.’ Wetherell was told to adhere to the official church religious creed. The Reverend Charles Chauncey was running into a similar problem down the road in England. He too was being told to “Cease and Desist.” [3] It is an ironic piece of history that both men would come into conflict with each other regarding their non-conformist beliefs.

Shortly after being cited, we find Wetherell, his wife, three sons, and servant aboard the ship Hercules, Captained by John Witherly and bound for a new world. They are in the company of several other men from Maidstone, possibly from the same church. A person had to have a license to leave England and the Wetherells were permitted to leave from Maidstone. Captain Witherly’s ship was registered at a home port of Sandwich. Historians and geneologists believe that Captain John Witherly is a Wetherell. Yet another spelling within the same immediate family.

The Wetherells settled briefly in Charlestown at the same time that Reverend Peter Hobart’s wife was living and apparently dying in Charlestown. Wetherell established the first grammar school there in Charlestown. He enjoyed the status of a freeman and was considered part of the gentry. He moved to Newtowne (Cambridge). Records of real estate sales are often one of the few footprints left by our ancestors. Fortunately, such deeds were often well maintained in the new colonies. As long as invading armies did not burn the courthouse down, we are in good shape. In March, 1635, Wetherell sold a Cambridge house and 12 acres on the south side of the Charles River to John Benjamin and in 1638 he sold his second Cambridge house and four acres on the southwesterly side of Garden Street to Thomas Parish. Garden Street is still there today and the property is adjacent to present day Harvard Yard. In fact, when the Colonial Patriots created their bunkers at the start of the Revolutionary War the fortress included the front lawn of Wetherell’s former (1638) residence. Good thing they got out of there when they did. They might have lost a few windows during that week.

The sale to Thomas Parish freed up the Wetherells move to Duxbury, Plymouth Colony in 1638. Duxbury had only recently been founded as an approved village and the village had received permission to open a church. The community property was largely held by the original pilgrims: William Brewster, Miles Standish and John Alden. Wetherell found what he needed in a church: beliefs similar to those he held dearly in England. The Reverend was identified as a ‘proprietor’ in 1640. Those several “men of Kent” who had sailed with the Wetherells to New England, also settled in the area. This pattern repeats the pattern we saw with Obadiah Bruehn and the Blynman party, as ’several respectable Welsh’ had traveled with Richard Blynman. And we see it now as Pilgrims disband, leave Plymouth and move up the coastline in the direction of Boston and Providence, Rhode Island. The Pilgrims were free to move after 1627 when their contractual obligations to Plymouth Colony Proprietors in England were fulfilled.

The sale to Thomas Parish freed up the Wetherells move to Duxbury, Plymouth Colony in 1638. Duxbury had only recently been founded as an approved village and the village had received permission to open a church. The community property was largely held by the original pilgrims: William Brewster, Miles Standish and John Alden. Wetherell found what he needed in a church: beliefs similar to those he held dearly in England. The Reverend was identified as a ‘proprietor’ in 1640. Those several “men of Kent” who had sailed with the Wetherells to New England, also settled in the area. This pattern repeats the pattern we saw with Obadiah Bruehn and the Blynman party, as ’several respectable Welsh’ had traveled with Richard Blynman. And we see it now as Pilgrims disband, leave Plymouth and move up the coastline in the direction of Boston and Providence, Rhode Island. The Pilgrims were free to move after 1627 when their contractual obligations to Plymouth Colony Proprietors in England were fulfilled.

We find Wetherell located in a new land, with families sharing similar beliefs, from Kent, England. Thus, the behavior pattern of The Great Migration has been established:

1.Develop a sense of who you are in your relationship with God.

2. Have the courage to live what you believe.

3. Bring down the wrath of Archbishop Laud on yourself, your family, your congregation and community.

4. Flee the country with your friends and neighbors and

5. Then move four or five times until you and your pals find a church and state that works for you.

Wetherell was called to preach in Scituate, Massachusetts Bay Colony. The departure of the Reverend Lothrup left the Scituate church divided. Part of the congregation wanted to invite Charles Chauncy, Wetherell’s peer back in England, to serve as preacher. The other less than half of the congregation wanted to install Wetherell as their preacher. Reverend Chauncy had been embroiled in a controversy down the road in Plymouth Colony and some parishioners did not want to get entangled in a controversy.

Baptismal procedure was at the heart of the debate in Plymouth. Chauncy believed full immersion was the only valid way to baptize someone in the name of The Christ. Separatist Elders in Plymouth believed sprinkling water over the body was equally valid. Chauncy was a relative newcomer in New England and had not yet come to recognize that a cold, harsh New England climate could turn a heart warming baptism into a heart stopping polar plunge.

The religious leaders of the Plymouth Colony held public debates, trying to convince Chauncy to change his views. The harangue sounded something like this:

‘Jumpin’ Jehoshaphat, man! Do you not have any idea what it’s like to be dumped into a cold bath in December? Or don’t you bathe in the winter? You must bathe and you can’t tell me your privies don’t back up into your abdomen! And you say you want to attract people into our congregation? You’ll scare ‘em away! Just sprinkle a little water over their foreheads and call them saved. You aren’t going to anger the Good Lord by showing a little common sense and concern for our harsh weather!”

When Chauncy still did not change his views, the Plymouth leaders wrote to congregations in Boston and New Haven soliciting their opinions. Attempts to use Survey Monkey fell flat without the Internet. All the congregations wrote back that both forms of baptism were valid, but sprinkling made more sense in the winter, which in New England meant October through May. Despite all the efforts, Chauncy did not change his approach. During the regional debate, William Wetherell authored letters expressing his views and his common sense approach, recognizing the climate as a factor. The majority in Scituate recruited Chauncey. He was a learned man with much charisma and a fire in his belly. A large minority of the parishioners remained dubious.

It was in 1642, in Scituate, that Chauncy practiced what he preached. In a public ceremony, with a bit of hoopla, he baptized his own twin sons in a full immersion ceremony. The plan backfired when one of his sons passed out as he was dunked in the water. The mother of a third child, who was supposed be baptized at the same event, refused to let it happen. Her son would not be baptized that day, in that way. She made the perfectly clear. Chauncy would not lay his hands on her boy. In fact, according to Governor John Winthrop, mom got a hold of Chauncy and “near pulled him into the water”. The whole scene went viral by the end of the week.

The Wetherell supporters in Scituate had to be saying, “I told you so.” Reverend Wetherell offered a low key, amiable, authentic approach to preaching that appealed to the second contingent of the original congregation. Plans to settle the matter in a winner take all croquet match never developed. The Chauncy faction asserted its’ will and the Wetherell followers decided that it would be necessary to start a Second Church of Scituate. William Wetherell was invited to be their minister. Apparently Wetherell’s letters expressing his viewpoint were critical in gaining approval not only locally but in the offices of big shots like Governor Winthrop and Cotton Mather. His letters remain archived at the Second Church of Scituate. Wetherell was ordained Pastor on September 2, 1645. He held this position until his death on April 9, 1684.

The animosity between the two churches continued until Chancey accepted a position in Boston as head of a start up college they called Harvard University. When Chauncy was hired to be President of Harvard, he had to promise the leaders in Boston that he would keep his views on baptism quiet. He remained at Harvard until his death. Scituate church records indicate intermittent friction after Chancey’s departure. In 1672, a Josiah Palmer was fined ten shillings for speaking “opprobriously” of William’s church. His complaint: “Mr. Wetherell’s church is the church of the Devil!” didn’t sit well with the clerics of New England. Imagine the fines we could levy today if a person could be fined for dissing another church or politician?

Wetherell’s church was a small building, which, in his later years, fell into disrepair as he declined in health. The parish never provided a parsonage and he and Mary fended for themselves in terms of housing and supplementing their income. They were providing for nine children, servants and several barnyard animals, who in turn, helped put food on the table. The Reverend was renown for his fine sermons and his creative writing efforts. A pattern emerges: there is a tendency among Puritan preachers to dabble in writing journals, poetry, essays and sermons. Wetherell’s early letters on baptism and his growing reputation as a gentleman preacher drew several notable families into Scituate for family baptisms: Kenelem Winslow (then of Yarmouth), Governor Josiah Winslow and Nathaniel Winslow, and the Rogers family of Marshfield all brought the children to William Wetherell for a baptism.

The last child the Reverend William Wetherell baptized before he died was apparently his own grand daughter. His death is recorded in the Scituate church records by Samuel Deane in the following script:

“Abigail the Daughter of Isreal Hobart, March 16th, 1684, baptized by our late pastor, William Wetherell”.

Isreal Hobart was married to William’s daughter, Sarah. Isreal, born in 1642, was the son of our Peter Hobart, Pastor in Hingham. That would make infant Abigail the grand daughter of William Wetherell and Peter Hobart. On April 9th, 1684 William was deceased. Peter Hobart had arrived in Heaven 5 years earlier, having died in 1679. So we have Wetherells, Pecks and Hobarts all gathered for a great game of Dominoes beyond the Pearly Gates. I wonder if Winslow is trying to turn a profit wagering on the game?

There a number of intersections of our family trees that emerge in New England in the 1600’s.

Wetherell’s daughter Mary (b. 1635) married Thomas Oldham (b. 1624) in Scituate in 1656. Thomas is the son of Thomas Oldham and Elizabeth Rhodes who arrived in Plymouth one year after the Mayflower had arrived. Oldhams are found in the Stille/Rogers branch of the Smith tree and will be subject to elaboration.

Reverend Wetherell’s son Daniel (b. 1630) married Grace Brewster (b. 1639) in 1659 in New London, CT. Grace was the daughter of Jonathon Brewster and Lucretia Oldham of Plymouth Colony. Jonathon was the son of Mayflower Pilgrim, William Brewster and wife Mary. Lucretia is a sister to the previously mentioned Thomas Oldham.

Theopolis Wetherell (b. 1636) in Scituate married Lydia Parker (b. 1653) in 1675 in Scituate. Lydia is an ancestor in the Parker family branch of the Slaymaker tree. Again, it was a small world and a small population.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

We have set the stage for Abraham Pierson by having already introduced one of his lifelong side kicks, Obadiah Bruehn.

Abraham Pierson (a Whittington ggf) was born in Yorkshire, England and graduated from Trinity College at Cambridge in January of 1632. He was Episcopally ordained at the Collegiate Church in Nottingham in 1632. In 1639, he came to Boston from England with brothers, Henry and Thomas. His wife, Abigail, was the daughter of Reverend Jonathon Wheelwright, who we met previously in the Antinomian Controvery in Boston. Pierson’s daughter Abigail (born in 1644), would marry Jonathon Davenport, Jr. the son of the famous preacher, John Davenport, Sr., close friend of John Cotton. We will eventually add John Cotton to the tree by way of his son, Seaborn Cotton. You will recall that Cotton so named his son as the child was born on the voyage to Boston.

Reverend Pierson was appointed by a council of Congregational ministers in Boston in October, 1640, to serve as pastor for 40 families who were leaving Lynn, Massachusetts. They felt restrained in the practice of their beliefs and headed to the western end of Long Island, hoping to establish themselves in the location on Manhattan Island previously deeded by the English to the Pilgrims in 1620. But the feisty Dutch had already secured the future home of New York City and, in a show of force, the Dutch drove the English settlers off. Pierson’s congregation immediately collected their goods and sailed eastward and bought land from the Indians advertised as ocean front property with a view. It was on the northeast shore of Long Island that they founded Southampton. This was the first town settled by the English in the present day state of New York. Imagine the paradox: a conservative Congregational preacher laying the groundwork for the Hamptons and future home of the rich and famous, including the Kardashians.

Pierson established the township of Southampton and the Congregational Church. In his mind, they were one in the same, church and state. He had in his congregation a young entrepreneur, a man of Welsh descent known as Obadiah Bruehn. They would remain together for life, the preacher and the Welsh CFO, along with the Kitchells and Scheaffes and Baldwins, etc. They remained in Southampton until 1644 at which time the church divided and the greater share of the congregation chose to become Presbyterian. A majority of the Southampton residents also chose to become affiliated with the colony of Connecticut, for purposes of governance, instead of the New Haven Colony. This was a slap in the face to Pierson who was adamant in his disdain for Connecticut and love for New Haven.

At some point between 1640 and 1650, Bruehn and his original preacher friend, Richard Blynman took separate paths. You will recall that Bruehn and Blynman first came to the New World together and settled with Edward Winslow in Marshfield, then Gloucester. Obadiah was the town clerk in Gloucester and when he left the village the official records disappeared. He was charged with taking them. Extracts, written in his hand, were later found in New Jersey. Local legend had it that the village of Gloucester would not pay for his efforts and so he considered the property his to take. Others argue that evidence indicates otherwise: he did leave Volume II (written in his hand) behind in Gloucester and therefore:

‘Volume I has to be here, somewhere. Has anyone looked under the altar?’

Records were some times taken with congregations as a way of protecting not only their financial investment but their identity as well. Puritans were still feeling a bit insecure in terms of life and limb. Reverend Blynman does end up back in England with the death by beheading of King Charles I.

Around 1647, a disappointed Abraham Pierson moved his family from Southampton to the north shore of the Long Island Sound, establishing Branford in what is now Connecticut. At that time, Branford was affiliated with Pierson’s preferred choice, the ecclesiastical New Haven Colony. Pierson remained in Branford for 20 years, he “enjoyed the confidence and esteem not only of the ministers, but the more prominent civilians connected with the New Haven colony.” His star was rising among the clergy of New England. Governor Winthrop identified him as “a Godly learned man,” and Cotton Mather reported that “wherever he came he shone.”

A number of the Southampton congregation left with Pastor Pierson and merged their congregation with a group from Wethersfield, Connecticut and all agreed: Pierson was their preacher. New Haven was an autonomous colony, operating independently from the Connecticut Colony. Two different patents, two different companies were engaged in the development of each colony. The culture in the colony of New Haven was vastly different from that in Connecticut Colony. Church and State were one in the same in New Haven, as was true in Massachusetts. A person had to be a member of the church in New Haven, in order to secure freedom, rights and privileges. Civil Rights were tied to church membership. Connecticut Colony separated church and state to the extent that one did not have to necessarily be a member of a preferred church to hold the rights of a citizen. Pierson’s congregation believed their Congregational Church should own and operate its own colony exclusively. Who could blame them for holding to this belief? They were fleeing England, a land in which intolerance was considered a virtue. If each church could have their own colony we might all live to an old age. Nevermind the economic forces that might drive a wedge between us all.

In 1667 Abraham Pierson would be on the road again. The events that forced his departure are an important part of New England history. In response to a petition presented by Obadiah Bruehn, John Winthrop and 17 other dignitaries, King Charles II issued a decree granting a charter to Connecticut. The decree did not do what Bruehn had hoped it would accomplish. The King forced New Haven colony to merge with the Connecticut colony. New Haven and several townships resisted. These young, vibrant communities had identities all their own and a fierce local pride similar in vein to a small town’s dedication to their local high school team.

Pierson united with Jonathon Davenport (Junior) in heated opposition to the union of the two colonies. As an elder statesman in his church, Pierson was a man of firm convictions. He despised what he viewed as the laxness and liberality of the clergy in Connecticut. He differed with regards to infant baptism and church communion. He insisted that no person in the New Haven colony could be made a freeman unless he was in full communion with the church. He fully agreed with Davenport and others in the colony, that no other government than that of the church should be maintained in the colony. Any thing else would mess with the ‘order and purity of the churches’.

Their efforts were futile. The rancor disturbed many good citizens on both sides of the issue. Those 19 leaders who had petitioned the King had not necessarily considered that the charter would demand the two colonies merge. Nothing was more important to New Haven citizens as their belief that church and state are one in the same. Members of the church had rights that non-members should not possess. If the King’s will was to be done, and New Haven united with Connecticut under one roof, then it would be time to move. Put Willie Nelson on the stereo and play it loud: “On the road again…”

In 1666, Pierson, with many families from various New Haven villages loaded their wagons and moved again. The villages of Branford, New Haven, Milford and Guilford emptied out. It reminds me of the plight of Johann Schleyermacher (ggf Slaymaker) leading the congregation from Seibersdorf into the lands of King Frederick’s Silesia. The New Haven contingent migrated to New Jersey. Had they been able to look into the future and realize that this would mean giving up the New England Patriots for the New York Jets, they may have never completed the move. But, football had not yet been invented, so it was a moot point.

A complaint was filed in Branford, CT similar to the complaint in Gloucester. Obadiah Bruehn was accused of leaving town in possession of the official records. The books that exist in the church library predate Obadiah’s term in office and those that were created during his term as clerk, are in his handwriting. The man was plagued by critics who promulgated rumor and innuendo. Who would think that church going, God fearing people would conduct themselves in such a manner? Does that last sentence end in a question mark or exclamation mark? (Rhetorical question).

The Pierson congregation got a fresh start, a new church, in 1667. They purchased land of the Indians on the Passaic River and laid the foundations for a village they named New Ark, present-day Newark, New Jersey. Sixty five able bodied men were counted in the party. Each man was entitled to a homestead lot of six acres. They brought their church organization (Presbyterian) with them from Branford, and became the first church of Newark. For 12 years Abraham led his flock of devoted followers; and lived his life, full of piety to God, and service to his fellow men.

Pierson had a strong interest in mission work, especially among the native population. As we have seen in previous family histories (van Couwenhovens, Stilles and Davis) interracial conflicts and attacks were common along the eastern seaboard. In 1659 Pierson published a pamphlet, “Some Helps for the Indians, showing them how to improve their natural reason, to know the true God and the true Christian Religion.” To his credit he learned the language of the tribe, published work in their language, including a catechism, and he preached among them in their language. Historians report that Pierson was to the Indians of Connecticut and New Jersey, what Eliot and Mayhew were to the Indian of Massachusetts.

While Pierson’s mission was noble and his intentions good, he was met with suspicion. From the arrival of the first Europeans, be they St. Brendan, the Vikings, the fur trappers or Puritans, the Native American’s perspective was entirely different from that of the white settler, and men like Pierson. The words of tribal leaders reveal the canyons of difference that Pierson would have to bridge.

The local Delaware Indian oral history observed:

“The great man wanted only a little, little land, on which to raise greens for his soup, just as much as a bullock’s hide would cover. Here we first might have observed their deceitful spirit.”

Indeed, when Wolphert von Couwenhoven purchased the first Dutch lands in Manhattan, the Indians did not understand land ownership and thought they could continue to hunt the property and plant crops. When Wolphert’s sons sought to annihilate them, the Indians were left with little recourse but to strike back.

Preacher Pierson was dealing with that harsh reality and more. The Indian was told that he was a wild savage living in a wilderness without God. Again the chiefs responded eloquently:

“We did not think of the great open plains, the beautiful rolling hills, and the winding streams with tangled growth, as ‘wild’. Only to the white man was nature a ‘wilderness’ and only to him was the land ‘infested’ with ‘wild’ animals and ‘savage’ people. To us it was tame. Earth was bountiful and we were surrounded with blessings of the Great Mystery. -Chief Luther Standing Bear

Pierson’s devotion to God and the Bible was genuine, but even his Bible was suspect to the Native. In the words of Tatanga Mani, a Stoney Indian:

“Oh, yes, I went to the white man’s schools. I learned to read from school books, newspapers, and the Bible. But in time I found that these were not enough. Civilized people depend too much on man-made printed pages. I turn to the Great Spirit’s book which is the whole of his creation. You can read a big part of that book if you study nature.”

The Native the European sought to convert was not the unthinking savage stereotype that suited the white man’s need to conquer the “wilderness.” Plenty-Coups, a Crow Indian, adds insight into the Native’s perception of the white man’s religion

“Wise Ones said we might have their religion, but when we tried to understand it we found that there were too many kinds of religion among white men for us to understand, and that scarcely any two white men agreed which was the right one to learn. This bothered us a good deal until we saw that the white man did not take his religion any more seriously than he did his laws, and that he kept both of them just behind him, like Helpers, to use when they might do him good in his dealings with strangers. These were not our ways. We kept the laws we made and lived our religion. We have never been able to understand the white man, who fools nobody but himself. “

Abraham Pierson’s contributions during his lifetime are precious and well respected by all men, white and Native. He was accepted as a good man, whose acts conformed to his words. He walked his talk. He died on August 9, 1678 and his descendants would continue his good work in terms of education and mission work.

His son, Abraham Jr, a Whittington great uncle born in Lynn, Massachusetts Colony, in 1641, graduated Harvard in 1668 and was ordained as a minister in 1672. His story will follow.

A Whittington great grandmother (daughter of Abraham Sr) Grace Pierson (b. 1650 in Branford CT, married ggf Samuel Kitchell and they had ten children. It is through Samuel and Grace that the Whittington family lineage descends.

Abraham Senior’s daughter, Abigail (gga), b. 1644 married John Davenport Jr. (ggu and son of John Davenport, 1st minister of New Haven) in 1663, at Branford, CT. John Davenport, Sr. was with Cotton and Hutchenson through the Antinomian Trials in Boston and he was the Founder of New Haven.

One of Abraham’s most illustrious descendants, Arthur T. Pierson, (1837-1911) was a powerful Presbyterian preacher who championed the need for passionate mission work. A prolific author (fifty books) and 13,000 sermons, he was popular on an international level at a time when world travel meant many weeks at sea.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

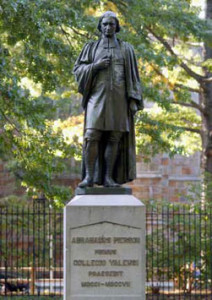

Abraham Pierson Location: Old Campus A bronze statue honoring Abraham Pierson (1645-1707), the college’s first president. Lacking a likeness of Pierson, Irish-born sculptor Launt Thompson used portraits of the rector’s descendants to compose an idealized face. The Shakespearean actor Edwin Booth may have posed for the work, lending it all the dignity and force that made Booth’s portrayals of Hamlet famous on the stages of New York and London.

The Reverend Abraham’’ Pierson II was born in 1646 while his mom and dad were living in Southampton. This data conflicts with other evidence that he was born in Lynn, Massachusetts in 1641. His gravestone reports 1646 and that jives with the fact that he was at Harvard from 1664 to 1668. He spent his childhood in Southampton and Branford; and it was in Branford that he met and married Abigail Clark. She was the daughter of George Clark of Milford. Abe Junior graduated from Harvard College with the class of ’68. Like his father he was ordained a minister in the Congregational Church. He followed his father to the new settlement of Newark, New Jersey.

I should make it clear, that this Abraham (Junior) is not a great grandparent in the family tree, rather a great uncle to Whittingtons. His sister, Grace Pierson Kitchell, is a great grandmother. But, Abe Junior has an illustrious career as a major player in American history. While history doesn’t include him in the same illustrious category with the George Washington and Thomas Jeffersons of the world, in the history of education he is a star.

The village of Woodbridge, just down the horse path from Newark, sought the young Junior as their pastor. The Newark congregation did not want to let him slip away for several good reasons: He was talented, a chip off the old block and the heir apparent to his father’s position. Senior was advancing in years and needed an assistant, so the town locked Junior in as their assistant on July 28, 1669. When dad died in 1678, Junior ran the show as thee go to pastor until 1692. It has been reported that Abraham moved after a startling dream. In that dream he clearly saw the image of an angel who told him to leave New Jersey now. The angel warned him that a man named Chris Christie, dressed in an orange sweater, would become governor in New Jersey and that Pierson should flee before the bridge to New York was closed. I find no evidence to support these reports of the dream, but plenty of evidence that the bridge did close.

In 1694 Abraham Pierson was ordained as pastor of the church at Killingworth, Connecticut. He was one step closer to his dream job. The English pioneers in the new world were conditioned to want and need the things they left behind in old England. If they were going to make it in New England there were certain things they had to have. And, they needed a decent system of education. Massachusetts broached the subject early on with parochial and public schools and with the creation of Harvard University in 1640. As children grew, the wealthy could afford to wave goodby to a young teenager and send him off to Oxford or Cambridge and now Harvard. But, what of the rest of us who either couldn’t afford that commitment or didn’t want to be so far removed from our children.

Colonists in Connecticut realized that they had their own fair share of scholars and academic types. Why encourage a brain drain to England when we need the talent here? Furthermore, Connecticut preachers were appalled by the liberals that were coming out of Harvard. Never mind the fact that many of the Connecticut preachers were themselves, Harvard grads, Pierson among them. It had been thirty years since graduation day for Pierson and at this point in history, the Puritans of Massachusetts appeared to be losing their God fearing minds.

‘Before you know it we might find Bostonians bowling on Sunday afternoons!’

‘God forgive the lot of them. Sinners all!’

To fight the good fight against the wicked liberals, ten God fearing preachers joined together and developed a business plan for the Collegiate School of Connecticut. Short on cash, they couldn’t come up with a building in which to host classes or even an office to which a candidate could send an application for enrollment.

The original Board of Directors, which included Junior, liked the idea of having a man like Junior as their lead Professor, but Pierson couldn’t secure a release from his job as preacher in Killingworth to teach in Saybrook. Alterations were made in the business model. Pierson could preach in Killingworth (keep his day job) and teach classes for the college. They wouldn’t need a building: Pierson could host classes in his home. It was a meager beginning for a fantastic college that would become known as Yale University. Pierson was identified as the first rector of Yale. I would argue he didn’t wreck it at all but got it off to a fine start.

So, let’s call him the first president of Yale University. I would also suggest that the present Board of Directors take a hard look at that name ‘Yale’ University and rename it ‘Pierson University.’ Oh, I know all about branding and the importance of name recognition. But when the world learns more about Elihu Yale, I think his heavy involvement in human trafficing, abductions, slave trading and the manner in which he stole and embezzled his way to his fortune will become an issue. And while Elihu Yale did bequeath a large fortune to the University, the college was never able to lay hands on the donation. The Britishgovernment was going to take back what he had stolen from the UK before they let anyone else have a crack at what was sitting in his cookie jar. A reasonable man or woman today could say, “Hey, we don’t need to tie our future to this man’s past!”

And by the way, Pierson donated 400 books from his father’s shelves to the original library of Yale and he gave the last six years of his life performing the duties of president, rector, teacher, pastor and probably custodian while cleaning up the house after classes. Credit should be given to Abigail, his wife, for supporting this effort. Anyone who has hosted a frat party in their home knows how much mayhem can be created by a Godly horde of preacher types.

Pierson died on May 5, 1707 at Old Killingworth (now Clinton) Connecticut. His life is celebrated with two statues commemorating his contributions: one in Old Killingworth and the other on the grounds of Yale University in New Haven. That’s right, they finally moved the operation out of Junior’s living room.

Sprague, in his Yale College and its Alumni says :

“And first comes Abraham Pierson (among the presidents) a man around whose character and history, the shadows of a century and a half have gathered, but who has still left memorials enough of his honorable and useful career, to insure immortality to his name. The cause of education he looked upon as twin-sister to the cause of religion ; and hence he was identified with the project for establishing the college, and not only his high appreciation of learning, but his own liberal attainments, designated him as the proper man to be placed at the head. His death produced a double chasm, and both learning and religion wept beside his grave.”

Stearns says,

“You perceive in him one of the best specimens of the first growth of the American colonies. And tradition represents him as an excellent preacher, and an exceedingly pious and good man.”

Trumbull in his History of Connecticut says,

“He had the character of a hard student, a good scholar, and a great divine. In his whole conduct he was wise, steady, and admirable: was greatly respected as a pastor, and he instructed and governed the college with general approbation.”

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

There are a number of other non conforming preachers in our families who arrived in New England, including the Deacon Lawrence, who traveled with Obadiah Bruehn and Abraham Pierson to Newark. The Deacon’s daughter, Esther (1651-1697), would marry Obadiah’s son John (1646-1695). Their daughter Sarah Bruehn (1679-1745) hitched up with Abraham Kitchell (1679-1741) and their child John Kitchell (1713-1771) marries Keziah Ball (1723-1789) thus linking together a century of families that began with roots in England and stayed together through thick and thin in New England and New Jersey. Keziah Ball descended from Pecks, Thompsons and Blatchleys… all of whom had been connected to Obadiah Bruehn, Abraham Pierson and a variety of other players in the initial stages of the Great Migration to America. Among these second and third generation descendants there were also preachers.

A second wave of migration will follow: that of English Cavaliers fleeing the wrath of Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan force and finding comfort in the hot and humid confines of the Virginia wilderness.

A third migration will also take place as early settlers like the Osbornes, Parkers, Stilles, Smiths and Sullivans gravitate westward across the Appalachians into Vermont, Pennsylvania, western Virginia, Ohio and eventually Illinois.

FOOTNOTES and LINKS WILL BE ADDED

READ NEXT: OLAF AND AXEL’S NEW SWEDEN ADVENTURE