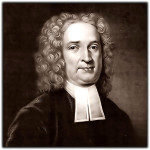

Reverend Robert Peck (1580-1658), a Whittington great grandfather, arrived in New England on the ship, Dilligent of Ipswich, captained by John Martin, the ship’s Master. The Dilligent sailed from Ipswich, Suffolk, in June 1638 and arrived August 10, 1638 at Boston, with about one hundred passengers, principally from Hingham, Norfolk (England), destined for Hingham, Massachusetts. The village of Hingham, Mass was the brainchild of religious dissidents. The founding fathers of Hingham, Mass were forced to flee their native village in Norfolk, England with both vicars, Rev. Peter Hobart and Rev. Robert Peck, leading the way. One year earlier (1637), Samuel Lincoln, an apprentice to Francis Lawes and 4th great grandfather of Abraham Lincoln arrived in Hingham, MA on board the ship John & Dorothy. Lincoln was a member of Peck’s St. Andrews congregation (England) and contributed to the development of the Old Ship Church in Hingham, MA.

The Norfolk church had wandered away from the strict Anglican doctrines imposed by Archbishop Laud. Unlike John Cotton, Reverend Peck was not known for remaining calm in the midst of an argument. English historian Reverend Francis Blomefield described Peck as possessing a “violent schismatical spirit”. What did Peck do to irritate Laud? A number of things. Peck objected to the Roman Catholic influence that Laud was reviving in the Anglican Church. Peck lowered the chancel railing in his church. Why should this offend anyone? It was the thought that counts. Puritans believed that the Anglican church had distanced itself from its parishioners. The altar railing created a visible barrier to the very public that the church served. It separated the privileged clergy from the masses and it flew in the face of the Puritan’s image of Christ, a man who washed the feet of a woman and mingled with the masses. Peck also antagonized ecclesiastical authorities with other forbidden practices [2]. Rumors that he played Mario Cart, Snowboard Kids and trafficked in Pokemon Cards are simply, not true. The charges against Peck were far more serious.

Archbishop Laud’s canon law forbade the right of worshipful assembly beyond the walls of the church. It was observed that Peck had gone so far as to actually sing a psalm with his family in his home on a Sunday evening. Peck then began hosting catechism classes (Bible studies, and prayer groups) with parishioners in his home. Such sessions were considered to be conventicles: secret worship services not sanctioned by law. When parishioners of Peck’s church broke into the church Peck was held responsible for their vandalism. It was charged that the Reverend “had infected his parish with strange opinions” and engaged in illicit behavior. Peck was a marked man, and the third strike against him required that he report to Parliament. He was called before a consistory court in Norwich and charged with “contumacious disobedience to the orders and ceremonies of the church.” I had to Google ‘contumacious.’ It means ‘stubbornly and willfully disobedient.’ Does that make the phrase ‘contumacious disobedience’ a redundant term? Laud clearly needed a grammarian on his team.

The Bishop Harsnet required a heavy dose of penance from all of Peck’s hooligans. They were to confess their errors and beg forgiveness. In his seminal work, Lives of the Puritans, author Brooks [1] notes that those who refused were immediately excommunicated and required to pay heavy fines. Bishop Harsnet’s journaled his decision that Peck “was driven from his flock, deprived of his bencfice, forced to seek his gread in a foreign land.” In the parlance of 2014, Peck was “unfriended.” Peck’s refusal to subscribe to the ‘new articles’ required excommunication. His congregation and his ability to provide a living for his family was stripped from him. He was left with little choice but to join those who were migrating out of England.

The cost to those who emigrated was steep. They “sold their possessions for half their value”, according to a contemporary account, and named the location of their new settlement after the old hometown that just kicked their butts out of town. The cost to Old Hingham was devastating. So many wealthy Puritans had fled Old Hingham that the remaining citizens were forced to petition Parliament for financial aid. The economy was crippled. Peck did bid farewell to his daughter who had married the son of the fierce, flame throwing preacher known all over England as “Roaring John” Rogers.

Peck’s arrival in Boston was perfectly timed if one likes the aftermath of what amounted to a political party convention in Bean Town. The streets were teeming with the angst that envelopes a community when injustice is created by those pursuing their twisted sense of truth. Puritans who escaped the axe of persecution in England, rather than conform, were now persecuting those Puritans who would not conform to the Puritan view of God and the necessary rules for worship in the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Reverend Peck had followed the trial of Anne Hutchinson from his home in Hingham, England. The charges against her were similar to the charges he had faced in England: gathering folks in the home for Bible Study. News traveled slower in those days. CNN, Instagram, Twitter feeds, Aljazeera were all standing in line behind the telephone, telegraph, and smoke signals, waiting to be invented. The news in 1638 was carried in a parchment letter deep in the pocket of a person who dared to cross the ocean in a wooden hulled ship with big white sails, laboring for two months to get home to England. Now we complain about 8 hour flights! Somehow the stories of Hutchinson’s travail got back to East Anglia and the Brits followed the story as closely as one could from 3,500 miles distant with a two month lag time in the news feed. It was just a bit better than peering at the petroglyphs on the walls of a Las Caux cavern, wondering what Paleolithic man was reporting 20,000 years ago. Protestants everywhere were curious to see how the church in Boston would handle a controversial topic that fired heated debates in the churches of England. Peck was crossing the Atlantic as Hutchinson’s two years of arraignment and trial came to an end in the Spring of 1638.

The Antinomian Controversy (the name given to Hutchinson’s battle with John Winthrop) pitted most of the Massachusetts Bay ministers and magistrates against the ‘free grace’ advocates, followers of the popular, charismatic and very likable John Cotton. Cotton felt the role of the Holy Spirit had been overlooked by the Church. He studied scripture and explored the role of the Holy Spirit. He was convinced that a person gained passage to heaven via the “covenant of grace” (spirit filled) as opposed to the notion of “covenant of works” (good deeds and indulgences will get me to heaven). He believed that those elected by God had the Holy Spirit dwelling within them.[10] The term antinomian is defined as being “against or opposed to the law.” [3] Cotton’s critics used the term to describe his “free grace” philosophy. Had they been running attack ads on television they would have used images of outlaws to cast the Cotton crew as not only immoral, but criminal: beyond the limits of religious orthodoxy. Wanted Posters would have been hanging in the Post Office. The charge of heresy was more than implied and death was waiting just around the corner for anyone carrying an ounce of Antinomian in their soul.

Cotton was apparently an astute politician. He shared his philosophy with his peers and watched as Anne Hutchinson, her brother-in-law (Reverend John Wheelwright), and the young governor of the colony, Henry Vane, passionately put forward Cotton’s non conforming ideas and agenda. Riding a wave of popular support from “free grace” believers, Vane unseated the Conservative John Haynes as the Bay Colony governor in 1635. Winthrop, a founder and frequent governor of the colony was deeply disturbed by the radical turn the colony had taken. Not one to turn the other cheek, Winthrop would strike back at the ‘free grace’ advocates with a vengeance and at Hutchinson in particular. No woman was going to mess with John Winthrop or act the way this ‘Jezebel’ [4] did in his colony. In October 1636, Winthrop took issue with Hutchinson on two points:

- Hutchinson felt the Holy Ghost dwells in a justified person (one destined for Heaven).

- She argued that works do not provide evidence that a person has been justified by God.

Historian Emery Battis, observed that Hutchinson induced “a theological tempest which shook the infant colony of Massachusetts to its very foundations” [5]. By the spring of 1636, John Cotton had become the focus of the other clergymen in the colony [6] Thomas Shepard, the minister of Newtown (later named Cambridge), wrote a letter to Cotton and warned him of the “strange opinions being circulated” among his Boston parishioners. Shepard also expressed concern about Cotton’s preaching, and some of the points of his theology [7]. Winthrop pursued Hutchinson within the courts of the state and church. Two separate trials were required by law: one to determine her standing in the community and the second her standing in the church. Winthrop would not rest until he was able to rid himself of his rivals. Somehow, John Cotton escaped unscathed. Winthrop sheltered his old friend from harm, just as Cotton’s superiors had done in Lincolnshire, England [8].

Hutchinson wasn’t necessarily in synch with Cotton when it came to her tactics. The Bible study groups that met at her home were not a small gathering of a few innocent women knitting one and pearling two while they rehashed the Sunday sermon or analyzed the plight of Moses. Twice weekly, Hutchinson opened her doors to sixty or more women. They met, ostensibly, to discuss and interpret scripture. Discussions easily turned into heavy criticisms of the orthodox ministers of the colony [9]. This was not a woman’s job in any church at the time. Henry Vane tapped into Anne’s energy. He encouraged Hutchinson to continue her efforts [10]. It was to his advantage to turn the Bible study group into a political action group. He seized the opportunity to organize the political base needed to unseat Winthrop as the party boss in Boston. While women couldn’t vote, women could influence the men of the house.

The aggressive challenges of the ‘free grace’ advocates to Winthrop’s control of the colony created wide dissension. Winthrop, realized that “two so opposite parties could not contain in the same body, without apparent hazard of ruin to the whole” [11]. He would adopt a stern approach to the difficulties, supported by a majority of the colonists [12]. Winthrop went to work, undermining the newly elected Governor Vane and attacking Hutchinson. Early exit polls indicated he had the growing support of the public beyond Boston. Governor Vane did not have the clout to stop Winthrop in his tracks.

In March, 1637, Hutchinson’s brother-in-law, John Wheelwright, was found guilty of contempt and sedition by the court “for having purposely set himself to kindle and increase bitterness within the colony” [13]. The vote did not pass without a fight. The Boston church was vociferous in support of Wheelwright and circulated a petition on his behalf. Those who signed would face dire consequences. Winthrop was bent on bringing peace to those in the Bay Colony who were clamoring for an end to the stress created by the schism. He would out the opposition, literally and physically. Winthrop studied Laud’s tactics in England. He was prepared for work and provided the firm hand he felt circumstances required. He would not be popular in Boston proper where the Hutchinson faction was followed with a fervent passion. He would operate from the burbs (Newtown/Cambridge) more often than not.

Winthrop’s return to formal power would begin at the General Court in May of 1637. His tactics were Machiavellian. Today’s politicians have clearly stolen a few pages from the Winthrop handbook. Vane’s one term as governor ended when Winthrop defeated him in a series of maneuvers that smacked of Wisconsin politics circa 2010. Authoritarian to the core, Winthrop viewed with great disdain the tenets of democracy that were appearing in the colony.

- Winthrop Rule #1: Hold the elections in areas you can win. Governor Vane could not stop Winthrop from holding the next election in Newtown, a suburb distant from Boston and away from Hutchinson’s home base.

- Winthrop Rule #2: Control the agenda. Vane wanted to present the petitions on behalf of Wheelright and draw support from the electors for the ‘Free Grace’ cause. Winthrop blocked Vane’s efforts. He did not want to allow Vane any opportunity to create a buzz.

- Winthrop Rule #3: Cut the opposition’s voice out of the election process. Winthrop’s delegation went with Winthrop to another area of the Newtown commons and elected a governor without Vane’s contingent. Not surprisingly, John Winthrop won the vote of freemen who were in his company.

- Winthrop Rule #4: Establish Residency Requirements that reduce the eligible voters for your opposition. The Winthrop contingent passed laws in the May meeting that refused citizenship to any newcomers in the colony who did not own the home within which they lived. If you got off the boat and did not have your home within three weeks, you were exiled.

- Winthrop Rule #5: Cut into the opposition’s representation in any assembly. Refuse to seat the opposition and/or expel them from the assembly if already present.

Controversy continued to tear the community apart. Vane understood where this could lead. He boarded a ship for London in August of 1637, never to return to America. He would put his talent to work for the Roundheads of Oliver Cromwell in England and eventually pay for his own non conforming mind when he was beheaded in 1662 by order of the King [14].

Winthrop and his conservative followers used the October, 1637 elections to stack the governing board with his followers. Only three of the thirty two Deputies were Free Grace advocates. All three (William Aspinwall, William Coddington and John Coggeshall) were from Boston [14].

The General Court on November 2, 1637 allowed Winthrop to tie a few loose ends together and cement his control over the colony. He would continue his ruthless attack on the remnants of the Free Grace contingency [14].

- Aspinwall was called forward in the November court, identified as a signer of the Wheelwright petition and dismissed.

- Coggeshall voiced his anger and he too was ejected.

- Bostonians replaced the two dismissed men with William Colburn and John Oliver.

- Oliver was identified as a signer of the Wheelright petition and was not seated.

- John Coggeshall was then called back before the court and charged with a variety of miscarriages, faulting him for the unrest in the community. [54] He was disfranchised (stripped of rights and privileges).

- Aspinwall was called forth again and charged with signing and authoring the Wheelright petition. Aspinwall was defiant and the court used his contemptuous behavior to banish him from the colony.[54]

- John Wheelwright was then summoned forth, disfranchised and sentenced to banishment. He was given two weeks to get out of Massachusetts.

- On November 7, the Court then brought Anne Hutchinson to trial, Governor John Winthrop presiding.

Winthrop had set the stage for his final act of vengeance. He had stripped the opposition and would now zap their spokesperson, Hutchinson. Women needed to know their place and he would use Anne Hutchinson to make his point.

The Civil Trial

When Vane left the country in August he deserted Hutchinson. He wasn’t the only one to leave her high and dry as she suffered in jail. Her husband left Boston as she went to trial and he headed out with Reverend Thomas Hooker to establish a new and separate colony in Connecticut. The Reverend John Cotton watched from his perch in the Boston church as the orthodox ministers flexed their dentures in anticipation of taking a few bites each out of Hutchinson’s hide. Hutchinson was charged with ‘traducing,’ using her home Bible study meetings (which were banned) to slander orthodox ministers and create havoc in the colony. Winthrop fumbled his attempts to press Hutchinson. He was stunned by her rhetorical skills. Frustrated, Winthrop had to rely on Thomas Dudley to carry the prosecution forward. Hutchinson held her own, sparring with Dudley on the first day of her trial. On the second day she noted that no one had yet witnessed against her. Witnesses were reluctant to take the stand. No one wanted to be caught in a lie in a Puritan setting of any kind, let alone under oath in a court room. No one wanted to witness against Hutchinson [14].

Three men testified on behalf of Hutchinson, including John Cotton. He did his best to relax the atmosphere, lighten the charges, blur the issues and make things go away. Despite defending herself well Hutchinson gave the clergy the evidence they needed to hang her when she proclaimed: “…take heed how you proceed against me—for I know that, for this you go about to do to me, God will ruin you and your posterity and this whole state” [15]. Hutchinson saw herself as a prophetess, “a mystic participant in the transcendent power of the Almighty.”[16] Her teachings empowered women whose status was determined by a husband or father[16]. For a woman to talk as she did was an open display of defiance toward the authority that men enjoyed by simply being men. Author David Hall suggests Anne degraded their authority [17]. Historian Emery Battis wrote; “She had defied the Court and threatened the commonwealth with God’s curse” [18].

Hutchinson was called a heretic and an instrument of the devil. The Court order was made clear by Winthrop’s pronouncement: “You are banished from out of our jurisdiction as being a woman not fit for our society, and are to be imprisoned till the court shall send you away” [19]. The Puritans sincerely believed that in banishing Hutchinson, they were protecting God’s eternal truth [20]. The Civil Trial ended and Hutchinson now waited to learn her fate as a member of the church. Seeking to facilitate peace in the colony, John Cotton elected to join a contingent headed to New Haven, Connecticut. The gentle and conciliatory Cotton, however, was implored to remain in Boston, where he continued to minister until his death. Perhaps the conservatives understood that all hell would break loose in Boston if they were viewed as chasing Cotton out of town.

Church Trial

Following her civil trial, Hutchinson was held in captivity pending trial by the clergy in March, 1638. She was rarely able to see her children. Winthrop was determined to keep her isolated and unable to lead. Various ministers made frequent visits to document the ‘errors’ in her thinking (evidence against her). Many of her supporters were either gone or compelled to silence. Her husband and other friends had already left the colony. The ministers confronting her in the Church Trial were basically the same cadre of orthodox clergy with whom she had sparred in her Civil Trial [21].

John Cotton’s role as he maneuvered through Hutchinson’s Civil and Church Trials is a curiosity. The judges understood his need to support her. His conciliatory nature allowed him to work with his ministerial colleagues and Hutchinson. Cotton was put in the uncomfortable position of admonishing Hutchinson, a person many Bostonians viewed as his disciple. Basically, his message to her amounted to this, and I translate the archaic English loosely and paraphrase it as follows:

“It is the overwhelming conclusion of this court that you, Anne Hutchinson, possess a whole bunch of unorthodox beliefs that outweigh all the good you have done around here. You are really dangerous and a threat to the mental health of this community. While we can’t pin everything on you, it appears that you have gotten a whole lot of people worked up in this colony and created a ton of undue stress in your wake.”

Remember, this is her mentor, John Cotton, peering over the paperwork as he pours on the heat. Is this man a hypocrite? A tool? A guy trying to walk a fine line to save his own butt? Will he stop at this point and let Anne breathe a little easier? Does he give her a Monty Python styled ‘wink, wink. Say no more. Say no more,’ to let her know he is just doing his job? No! He digs deeper and makes it personal. Tighten up your corset Annie! This Cotton isn’t going to feel like a gentle cloth as it wraps around the neck and goes for the jugular. My translation and paraphrasing of the actual passages follows. I will include the original message as a footnote at the bottom of ‘thee’ page [23].

“You can’t ignore the truth or dodge the obvious, Anne. The filthy sin of all women; and of all the promiscuous and filthy behaviors that occur when men and women get together is obvious. It follows that when men and women meet in the same location things happen and pretty soon the rumors fly about what is happening behind the closed doors. I haven’t heard anything myself just yet…. and I don’t think you have been unfaithful to your husband just yet, but who knows? If not already, it will happen. He’s been out of town for months. Just sayin’.”

Was Cotton reading from a script prepared by the right wing hard core conservatives on the Court? Did he really believe what he was reading? Why would he direct these comments at a BFF (Best Forever Friend)? Cotton was linking Hutchinson’s ideas to the extreme ‘free love’ behaviour credited to the antinomians and familists. Why would he participate in such a smear campaign? He concluded and I paraphrase:

“What we are doing here today is serving up some well deserved justice in the name of God. And in the name of God I admonish you. You have really hurt the Church, brought dishonor to Jesus Christ and done a whole lot of evil to many a poor soul in this area, (including myself I guess.”

Cotton then advised Hutchinson that she would be required to report back to the Court in one weeks time with her final response and plea. Again, Cotton’s role in this matter is a source of intrigue. Having ripped into her in the public court, he now received the permission of the Court to supervise her imprisonment in his home for the week. While hiding from the King in England Cotton had refused to recant, to admit wrong thinking and beg forgiveness. John Davenport had come to him at that time and failed to convince Cotton that there were errors in his logic. In fact, Cotton drew Davenport into his line of theological thought. They each fled England for the New World.

In preparation for her final presentation before the Clergy in Court, Hutchinson had the help of both Cotton and Davenport (who was staying in Cotton’s home). They advised her as she wrote a formal recantation of her “unsound opinions.” [24] How did such a strong willed woman with the help of two men who wouldn’t recant earlier in life, decide that she should admit to errors in her own thinking? Perhaps the fact that she could face death and leave her large family of children at risk weighed on her mind. Regardless, she crafted a carefully worded recantation and put herself at the mercy of the judges.

On Thursday, March 22, Hutchinson stood, and in a subdued voice read her recantation to the congregation. The sharks (judges) weren’t mollified. They wanted blood. John Wilson, a minister whom Anne had previously ridiculed in a private setting, was given the opportunity to read the court’s pronouncement of excommunication [24]. I paraphrase:

“You really messed up big time, lady. You have really sinned and offended this Church and God. Your thinking is really messed up and you have totally stressed a lot of good folks, and I mean ’totally.’ You have these phony revelations and you lie with the best of them and who knows what goes on in that home of yours! On behalf of the Lord Jesus I cast you out of our church and give you to Satan. From now on, we all see you as nothing but a heathen and a publican. You are a leper in our eyes and you need to get the heck out of our congregation and this colony. Buzz off.”

Hutchinson, her children, and several others packed it up and walked for more than six days through an April snow to get from Boston to Roger Williams‘ settlement at Providence, Rhode Island. Roger is a great uncle in the Smith family tree. He was the brother of 10x great grandfather, Sydrach Williams. In the second week of April, Hutchinson was reunited with her husband on Aquidneck Island (later named Rhode Island), in the Narragansett Bay. The strife took a toll on the man and he died in 1641 at the age of 55 [25].

Hutchinson’s departure from the colony was supposed to bring the controversy to a close. But the Bay Colony would continue on a course of intolerance toward women, minorities, the impoverished and on dissidents. It would not be as simple a task as banishing a woman or sect from their midst. The events of 1636 to 1638 are regarded as crucial to an understanding of religion, society, and gender in the early colonial history of New England. In his 2005 book on Hutchinson and the Free Grace Controversy, Winship writes, “Hutchinson’s well-publicized trials and the attendant accusations against her made her the most famous, or infamous, English woman in colonial American history” [26].

Within a week of Hutchinson’s sentencing, a number of her followers were called into court and disfranchised. Winthrop’s constables (his posse) toured through the colony taking weapons away from those who had signed the Wheelwright petition. A great number of those who signed the petition, faced with losing their protection and in some cases livelihood, recanted under the pressure, and “acknowledged their error” in signing the petition. Those who refused to apologize faced colony imposed hardships. In many cases these families decided to leave the colony even though they had not been banished [27].

Our ancestors, on all sides of our family, were caught up in the aftermath of the trauma. The Whittington lineage was especially rocked by these events in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Many in a line of ancestors were Puritan preachers and family, and/or followers devoted to a Puritan preacher who came to the Colony, fleeing injustice and seeking religious freedom. Their previous battles with the Church of England and Catholic Church now took a back seat, for a moment in time, to an entirely new Reformation of their own Puritan Congregations. The spinoffs were going to be incredible and tied back to previous reform efforts in Europe. Presbyterians, Episcopalians, Congregationalists, Baptists and Quakers would all emerge from the struggle that good people experienced as they tried to connect with a God they so desperatelly wanted to understand and please. If this life on Earth was going to have to be Hell, then Heaven was well worth the effort. How do we get there? That remained the burning question in the aftermath of the Antinomian Controversy.

The Bay Colony was not the attractive site it had once been to Puritan arrivals at the harbor. What kind of a Puritan was a person? John Cotton’s style was appealing in the Boston church. But, there was a lingering bad karma in the air. Conservative conformists might be comfortable in Cambridge, Salem, somewhere in the burbs. Those non-conforming Puritans who believed all citizens should participate in a full blown democracy might be drawn to Thomas Hooker’s Hartford Colony in Connecticut. The non-conforming types who wanted to keep control of the colony in the hands of those who are wealthy church members might try New Haven, a colony within the colony of Connecticut. Roger Williams was experimenting with a blend of church and state over in Rhode Island that was attractive to Wheelright and Hutchinson. Some just wanted the rural, rustic and rugged life of a Puritan living close to God and away from all the politicians. Wheelright chose the woods of New Hampshire (Exeter) and Maine. These were some of the choices facing our ancestors as they weighed their options. As we will see, few of them could settle in one place for very long. And some chose to head back to England when they thought they might be safer over there.

We haven’t seen the last of Anne Hutchinson. She will leave Rhode Island and head into the neighborhood of our Smith/Stilley ancestors: the Von Couwenhoven family, on the shores of Long Island Sound in New Netherland.

For more information about how the Antinomian Controversy impacted the Bruehns, Sheaffes, Balls, Kitchells, Allings, Blatchleys, Thompsons, Harrisons, Pecks and Baldwins another chapter will be added.

CHAPTER 6: THE GREAT MIGRATION

FOOTNOTES

[1] The Lives of the Puritans: Containing a Biographical Account of Those Divines who Distinguished Themselves in the Cause of Religious Liberty, from the Reformation Under Queen Elizabeth, to the Act of Uniformity in 1662

[2] Reynolds, Matthew (2005). Godly Reformers and Their Opponents in Early Modern England, Boyell Press

[3] Hall, David D. (1990). The Antinomian Controversy, 1636–1638, A Documentary History. Durham [NC] and London: Duke University Press.

[4] Winthrop, John: Journal entry when he learned she had been killed on Long Island.

[5] Battis, Emery (1962). Saints and Sectaries: Anne Hutchinson and the Antinomian Controversy in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

[6] Hall, David D. (1990). The Antinomian Controversy, 1636–1638, A Documentary History. Durham [NC] and London: Duke University Press.

[7] Winship, Michael Paul (2002). Making Heretics: Militant Protestantism and Free Grace in Massachusetts, 1636–1641. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

[8] Ziff, Larzer (1962). The Career of John Cotton: Puritanism and the American Experience. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

[9] Bremer, Francis J. (1981). Anne Hutchinson: Troubler of the Puritan Zion. Huntington, New York: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company. pp. 1–8.

[10] Winship, 2002.

[11] Hall, 1990.

[12] Battis, 1962.

[13] Hall, 1990.

[14] Battis, 1962.

[15] Morris, Richard B. (1981). “Jezebel Before the Judges”. In Bremer, Francis J. Anne Hutchinson: Troubler of the Puritan Zion. Huntington, New York: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company. pp. 58–64.

[16] LaPlante, Eve (2004). American Jezebel, the Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman who Defied the Puritans. San Francisco: Harper Collins.

[17] Hall, 1990.

[18] Battis, 1962, p. 204.

[19] Battis, 1962, p. 227.

[20] Battis, 1962, p.228.

[21] LaPlante, 2004.

[22] Battis, 1962, p. 246.

[23] Battis, 1962, p. 243. Cotton spoke: “I would speake it to Gods Glory [that] you have bine an Instrument of doing some good amongst us…he hath given you a sharp apprehension, a ready utterance and abilitie to exprese yourselfe in the Cause of God. You cannot Evade the Argument…that filthie Sinne of the Communitie of Woemen; and all promiscuous and filthie cominge togeather of men and Woemen without Distinction or Relation of Mariage, will necessarily follow…Though I have not herd, nayther do I thinke you have bine unfaythfull to your Husband in his Marriage Covenant, yet that will follow upon it. Therefor, I doe Admonish you, and alsoe charge you in the name of Christ Jesus, in whose place I stand…that you would sadly consider the just hand of God agaynst you, the great hurt you have done to the Churches, the great Dishonour you have brought to Jesus Christ, and the Evell that you have done to many a poore soule.”

[24] Battis, 1962, p. 244.

[25] LaPlante, 2004, p.228.

[26] Anderson, Robert Charles (1995). The Great Migration Begins, Immigrants to New England 1620–1633. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society. p. 395.

[27] Battis, 1962.