Gen 8: James Smith (1691-1749) of Bull Run, and Elizabeth Taylor

Father’s 4x Great Grandparents, Parents of Peter of Round Hill NC,

James Smith (father’s 4x GGF) was born in Westmoreland County in 1708, the son of ‘Peter Smith of Yeocomico,’ (a river upon which Peter lived). Peter of Yeocomico (Yo-co-me-co) also maintained a residence in the Nominy Forest and on Bull Run in Fairfax County. Our tree already includes two other Peter Smiths (Posey and Round Hill Peter) and this 5x GGF will be known as Peter of Yeocomico and/or Peter of Westmoreland. I tend to use the terms interchangeably and make no apology for that. Deal with it as best you can and don’t clog up my blog pages with any whining about it, for God’s sake, or my sake.

James was one of ten children identified in the will of his father (d 1741). Peter of Westmoreland does not identify his wife in his will, and it is therefore assumed she had passed away prior to Peter. The identity of Peter’s wife is the subject of much conjecture among the many Smith genealogists.

James Smith and wife Elizabeth started raising a family in 1732 when their daughter Elizabeth was born. She was followed by sons Peter (of Round Hill), William Bailey Smith, John, Presley and daughter Nancy Ann. Please notice the name, ‘Presley.’ It was common to honor the mother’s family by using a family surname as a first or middle name for a child. Thus, Presley Smith was named after the children’s grandmother Elizabeth Presly.

The Presley name was a big name in Virginia as was the Taylor name. Colonel Presley was a prestigious individual and a man of great wealth. The degree to which folks wanted to attach their family to his name becomes evident when researching 18th Century birth certificates in Virginia. A whole lot of guys had the first name, Presley, inked on their birth certificates.

Slapping a family surname on a kid’s forehead for a first name reflected a pride in one’s heritage.

The will of grandfather (GGF4) James, is dated October 14, 1749 and was probated on September 24, 1751. James designated his “loving wife Elizabeth” as “my executor.” Hugh Thomas (James Smith’s brother in law) was a witness. The Thomas boys were invested in land to the north of the Smith estate at Bull Run. The inventory attached to the will of James indicates that he owned stuff not found in the home of the average citizen at that time: valances, curtains and books, as examples. This indicates that he was a man of wealth, more so than not.

I can’t help but read his will and think of those folks who were identified as slaves: ‘one Negro woman named Janey,’ ‘one Negro woman named Sue,’ and ‘one Negro girl named Beck.’ Each of these women is given “to him and the heirs of his body” and “with all increase.” This is the language that locks a slave into the custody of the master and that master’s children. It also locks into the master’s custody any ‘increase’, that is: any child born to the slave. So human beings transferred from one household to the next along with the curtains, valances and library books. The one line in the will that really got me however was the mention of Anne’s entitlement in her father’s will:

“I give to my daughter Anne Smith the sum of 25 pounds current money or a young Negro at the discretion of my executors.”

That is correct. Anne could have either 25 pounds or “a young Negro.” She had a choice to make. If she chose to own a slave, the executors would pick one out for her. She could have the pick of the litter, if we are to think of slaves as chattel. Sadly, it was the way of the world. Unfortunately, our nation had to endure another 115 years of slavery before the Emancipation Proclamation launched a new era in American history and created new challenges in race relationships, challenges that remain unresolved to this day.

Elizabeth Smith nee Taylor, the widow of James, did rebound from his death and married James Lanman prior to 1767. Peter of Round Hill sold land in Caswell County to James Lamman (aka Landman) in 1789. Elizabeth and Mr. Lanman resided for a time in Caswell County. Elizabeth’s sons William Bailey Smith and Presley Smith also lived in Caswell, albeit briefly, and then headed north into Muhlenberg County, Kentucky. Kentucky proved to be an interesting stop for the Smith family migration from the Atlantic Coast to the Great Plains. Elizabeth’s daughter Nancy Anne Smith Boggess and husband Richard eventually moved to those 1000 acres Bailey helped her secure in Kentucky. How many of the ten Boggess children went with them I do not know. By the time the family matriarch, Elizabeth Smith Lanman nee Taylor, passed away, she had no children left in Virginia. It is not known when or where she died.

It is a curious note, finding a person like Elizabeth, born into wealth, and dying, perhaps unknown in the Kentucky wilderness. It was not unusual. The land beyond the Blue Ridge was one vast forest. It sucked up a lot of lives, just as the Atlantic Ocean had done with many dreamers. Survival required a hearty soul and skills not taught by the east coast tutors of the wealthy aristocrats.

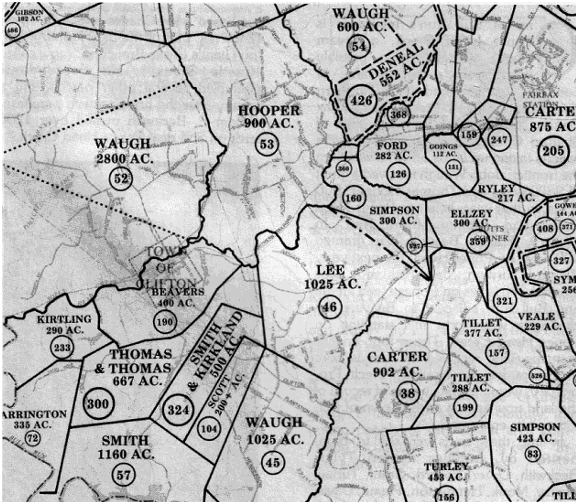

The Smiths shared the same neighborhood, churches and social events with illustrious families. The Carter family, Arringtons, and Lees all lived in the same rural Virginia subdivision with the Smiths from 1713 to 1750. Each had purchased 1000 acres to the south of Clifton VA on the creek known as Bull Run in soon to be Fairfax County (1742). Taylors are not shown on this plat map.

This map, a recent find on the internet has been of great importance to my effort to locate the very land upon which James Smith, son of Peter Smith, lived and died. Over the centuries many residents of Westmoreland and beyond have taken great efforts to preserve the heritage of a land referred to as the “Athens of the New World.” There are maps online that lay out the properties and owners in the 1650’s. There are also maps that reveal the deeds along the Bull Run waterway. I have found the exact location of the Smith family homestead at Clifton, on Bull Run, seven miles from the heart of the Battles of Bull Run, battles that would be fought 150 years later. I could drive south out of Clifton across the Davis Ford, onto Kincheloe Road and find Peter’s Bull Run Estate right where present-day soccer fields are found and stand where Peter Smith of Yeocomico and his son James once walked the earth. Davis and Kincheloes are several times great grandparents along with the numerous Smiths in this history.

Bull Run Properties, Clifton VA

Many of the families identified as property owners in this plat map are familiar names, not only in terms of Colonial and Virginia history, but in the early life of the Smith family. Peter of Yeocomico’s grandson, Peter Smith of Round Hill, was born at Bull Run to James and Elizabeth. He married Jemima Simpson, daughter of Richard Simpson (lower right and center). The Turleys (lower right) were neighbors on Doegs Neck (Potomoc marsh) in the 1650 and 60’s. The Lee family (center) also lived right down the road from Peter of Yeocomico in Westmoreland. One of the Thomas men, Hugh (left), married Peter of Yeocomico’s daughter Anne and he and his brother Daniel, held property to the north of the Smith estate. Another of the Thomas brothers (James) established the entire survey for all properties within this patent. The Carters gained status as thee wealthiest family in America via the tobacco industry. Robert Carter, grandson of King Carter, would release 500 of his slaves on September 5, 1791. He not only freed his slaves in the single largest act of manumission in American history, he also provided land and housing for each of the newly created freedmen.

Attempts have been made to connect Elizabeth to John Tayloe. John had a daughter Elizabeth, (b 1721), the twin sister of John Tayloe II. John I mentions his daughter in his 1747 will and a husband James Smith. But the facts don’t add up and records indicate she married a Corbin.

At any rate, James Smith never lived to see Mt. Airy surface on the face of the earth in 1764. He died in 1749 in Fairfax County. Searching for Elizabeth’s lineage brings to light an era of prosperity and great family wealth, one which she may or may not have enjoyed. Failure to look into matrilineal lines continues a pattern of chauvinism that suffocates one half of our population. We are a compilation of a lot of cool DNA! We miss a lot of details that make for entertaining campfire stories if we narrow our focus too much.

It is important to understand just how vast and insidious the Tayloe wealth became. The Tayloes managed a corporate empire with large scale operations in Virginia and Alabama. The Tayloes moved many of their slaves from Richmond County, Virginia to the Black Belt of Alabama between 1830 and 1860. There were Tayloe slaves in King George and Prince William counties in Virginia and Marengo County, Alabama. They had such a massive operation that they were forced to keep very good records. Fortunately for us, many of their records did survive and are housed at the Virginia Historical Society. There are around 100 microfilm rolls recording the names of human beings enslaved on Tayloe plantations and 27,500 documents related to corporate and personal affairs on file.

The Tayloes used slaves on their 35,000 acres of tobacco plantations in Virginia, and in their Neabsco iron works. The records use “surnames” for the slaves well before the end of slavery. This system allowed the master to distinguish their many slaves and track their genetic make up for breeding purposes. The Mount Airy ‘farm’ was a breeding ground for the finest horses. But the Tayloes were also well versed in the breeding of slaves for the lucrative slave market.

As the soil deteriorated in Virginia from overuse and the profitability of cotton increased, the Tayloes expanded their operations into the cotton belt of the deep south. With the Civil War looming large, the Tayloes moved many of their slaves deep into Alabama. One author writes:

“My ggg grandfather John Collins was in charge of bringing many of the Tayloe slaves from Virginia to Alabama. Because of his association with the Tayloes, he became a very wealthy man. Although he was never married, he did have many children through at least two slave ‘wives.’ Many of the mulatto Collins from Hale County claim John Collins as their ancestor.”

The author of the above quote, also a Collins, provided assistance to a young lady seeking to trace the history of enslaved ancestors. The young lade wrote:

“My name is Johanna Eatmon. My Eatmon family traces back to Warsaw, VA and Mount Airy. My husband’s great grandfather, Louis, was a slave there. My husband’s grandparents were sharecroppers at Brown’s Station, Alabama. I believe the Browns had business relationships with the Tayloes. At the onset of the Civil War part of the family was moved to the Black Belt region of Alabama. Along with other slave families- Wormley, Richardson, Ward and the Moores. My husband was born in Alabama and knows all of these families listed above. They still live in close proximity to one another. The GGGrandson of the overseer (Collins) who was hired to move the families south gave me these names.”

The number of slaves the Tayloes marched to Alabama was not a mere bus load. In a running thread regarding Mt. Airy, the Tayloes and slavery, author Tom Blake (3/8/2002) notes:

“Through my Large Slaveholder home page link below, you can find information on 3 Tayloe plantations in Marengo Co. AL, each holding 115, 125 and 150 slaves respectively. E.T. Tayloe held an additional 104 slaves hostage at Woodville in Perry Co. AL.”

Tayloes were not the only overlords moving their ‘stock’ into the deep south. The family surnames mentioned in Johanna Eatmon’s passage are the family names of the Westmoreland neighbors, friends and relations of our Peter Smith, a full 200 years prior to the Civil War. The Wormeleys, Moores, Wards and the Browns of Brown Station and many others attended church with our folks, served as pall bearers, officials for deeds, marriage licenses and wills.

Interesting patterns emerged as these migrations moved like Caribou across the face of the earth, from Atlantic coastal plains to the Great Plains. Surnames found in Westmoreland and Accomack in the 1600’s are bound together in wagon trains that follow newly established trails to places like Spartanburg (South Carolina), Caswell County (North Carolina), Muhlenburg (Kentucky) and Posey County (Indiana).

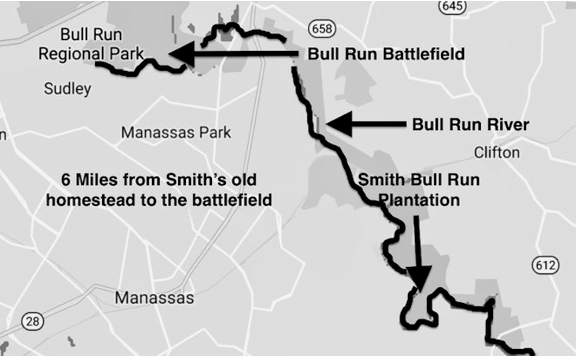

The Battlefield of Bull Run

James Smith lived on a property that was first purchased by his father Peter of Yeocomico, Westmoreland County, VA. To be clear, these Smiths preceded the Civil War by one hundred years. The proximity of the property to the battlefield is shown in a Google Earth image that follows. Peter of Westmoreland’s second plantation was 7 miles from the fields on Bull Run that were the scene of the first land clash of Union and Confederate forces. Our Smith family had moved on from Bull Run prior to the landmark battles. I am glad they got the heck out of there. The early demise of any one of my predecessors could have resulted in no result at all for me.

The first Battle of Bull Run, also known as Manassas, has been the subject of much documentation and recanted countless times. The nation has turned the site into a National Historic Park. Union generals assumed the battle would be the first and last battle of the conflict between north and south. They assumed the Union would win and the issues that had divided the nation for a century or more, would be resolved. The odds were so stacked in the favor of the Union that the good citizens of Washington DC traveled the 25 miles to witness the expected rout of the Rebels firsthand. It was an occasion for an entertaining picnic, the forerunner of NFL football festivities, replete with tailgating parties, fancy hats, gowns and garments of all kinds

Bull Run and Smith Estate

Google Earth: Coordinates: 38°45’15.45 N and 77°23’27.73 W.

Bull Run (the creek) follows that squiggly line from Peter’s front porch to the field of battle. It is little more than a five-mile hike. I am certain that the Smith family could have made a fortune selling paraphernalia and providing food trucks for the crowd of spectators who had come to witness the grudge match between Blue and Gray. I am equally certain that it would have been a nightmare to have witnessed any part of the events that occurred that day. Blood was shed in horrific manner, countless lives were lost, mayhem ensued, and the yanks were routed by a band of dedicated rebel men who were fighting for their homeland and the culture and economy that was engrained within their very soul.

In the aftermath of the struggle, the Union soldiers disappeared into the woodland, fleeing in helter-skelter fashion for a base camp in Washington DC. The woods were littered with the bodies of men who died of wounds while escaping. There was no organized retreat. Soldiers trampled citizens who were also fleeing the scene. The roads and paths leading away from Bull Run were laden with a most bizarre blend of bloodied soldiers and distressed damsels who were overdressed for the après battle occasion. The fields of the James Smith plantation to the east of Bull Run were witness to the chaos not only that day, but through-out the war as Robert E. Lee sought to protect the properties and rights of his ancestors and descendants.

Again, I need to be clear: James Smith had been dead for 110 years prior to Bull Run. His son Peter of Round Hill had migrated west to Round Hill and George Rudolphus Smith lived a full life, long before the Civil War. In fact, Peter of Posey IN was nearing the end of his military career when he donned his Union uniform one last time and led a band of geriatric soldiers to Cairo, Illinois. I do not know if the Fairfax (Bull Run) properties remained in the hands of the Smith family at the time of the Civil War. And while most of the death and mayhem of battle was to the west of the Smith plantation, the Bull Run creek was a major corridor and conduit throughout the Civil War. There were Smiths and allied families wearing blue and gray.

_ _ _ _ _

A reminder to our readers: many of the names found among these pages can also be found online. Simply Google the name, dates and places connected to that name and Voila! You will find more about a person or event. It may be necessary to add the name of a spouse in order to pinpoint the correct person. Failure to include a date may land you on someone’s present day Facebook page or in the current Police Records for a distant county in Virginia.