The Welsh Explorers and Immigrants: 1575-1803

An exploration of the Smith family name led to the family of Peter Smith of Westmoreland VA and the latter half of the 17th Century. We were stranded in history between Doegs Neck and the Nominy and Yeocomico Rivers and left to ponder Peter’s relationship with those of the Washington, Madison and Jefferson families (the offspring of whom would become known as “Founding Fathers” of our nation.

The migration of the Stilley family from Sweden to New Sweden and North Carolina is historically accurate and provides some colorful family lore. The von Kouwenhovens were the earliest of Dutch settlers in New Amsterdam on Manhattan and Long Island in New York. They pried the Hudson Valley away from the Algonquin Nation and established a viable agricultural and mercantile base that lent itself to successful European settlement of New York.

The family migration pattern in my father’s Stille family tree, including the path of grandmothers and grandfathers, is distinct: moving southward from the coast of New York and New Jersey into Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina. From the year 1675 forward, this family migration coincided with two significant schisms in colonial history: 1) the protestant reformation in America and 2) economic rebellions in Virginia and North Carolina.

As the population of Virginia grew, charters were developed, patents granted, and governments established. Virginia, at the beginning of the 18th Century (1700), included everything east of the Atlantic seacoast to the Mississippi River. A survey in 1728 clearly marked the boundary between Virginia and North Carolina. But for 75 years prior to that survey, settlers moved into the Albemarle basin of North Carolina unsure of their home address. Amazon and UPS expressed frustration in terms of providing decent customer service. Cable TV and Cellcom lobbied for control of the region but were never sure who they should approach with their bribes, stock options and innocent attempts at justifiable graft and corruption. Dominos gave up trying to deliver pizza.

At one point a management team suggested they brand themselves with a slogan, “Bern, Bath and Beyond,” a reference to New Bern, NC and Bath County. The measure failed to gain support. Our family was right in the middle of the formation of the colony and state of North Carolina. As a matter of fact, the Davis family you are about to meet was one of the chief players in the formation of the earliest English settlements at Sagadahoc ME (1607) and Jamestown VA (1607) and yes, they provide many times great grandparents in my father’s tree.

By 1810 the population on the coastal plain began moving inland. Churches that had once been growing large memberships and multiplying in terms of congregations were suddenly closing their doors and engaged in retrenchment. Families were bundling up their belongings, joining neighbors and heading into central North Carolina, Kentucky and the black soil belt of Alabama.

Hezekiah and Sarah Stilley left their home in Hyde County NC and the tidewaters for Illinois sometime in the late 1790s. They departed with little fanfare and slapped a bumper sticker on the back of their mule that read simply, “Go Bears!” This was an apparent reference to a Chicago football team which had yet to be invented in a city that did not exist, in a Native part of the world in which the people had closer ties to Quebec than Britain. At about that same time George Rudolphus Smith was leaving Kentucky and plotting his future in southern Indiana.

But who was Sarah Davis and what can be learned about her parents and family tree? The answer was yet another eye opener for this old history teacher. I thought I had seen it all when I exhausted all that could be learned about Stilleys and von Kouwenhovens. When I learned that William Shakespeare had taken time to write a play (The Tempest) based on the misadventures of my ancestors I took a renewed interest in trying to decipher Shakespeare’s English.

Meet the Davis Clan

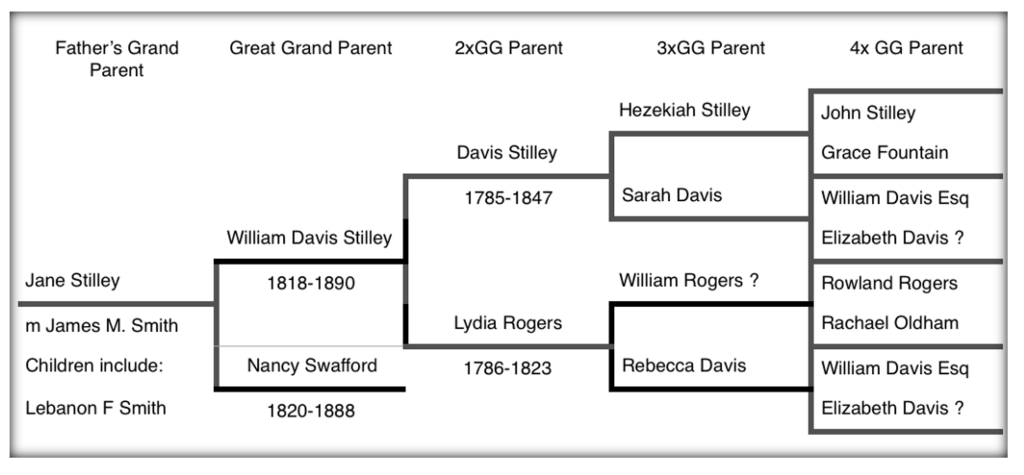

The name of Hezekiah Stilley appears to the left on Pedigree Chart 8 (p 142). I have provided a boatload of info regarding his parent’s (John Stille and Grace Fountaine) family tree. I covered his mother as best I could, and I apologize to my critics who have written to me complaining that I should have authored the section on Grace and the de la Fontaines in French. What next? The Stille section revised in Swedish and Wolfert’s bio in Dutch? I don’t think so. I have covered the descendants of Hezekiah as best I can and refer you to Pedigree Chart 2 if you need to refresh your memory as to his place in the tree as my father’s 3x Great Grand Parent in the lineage of Jane Stilley whose life’s journey took her from Southern Illinois to the Dakotas.

I owe it to Hezekiah’s wife, Sarah Davis, to include her family lineage in this growing volume. Sarah was the mother of 8 children, 6 boys and 2 girls. Several of the first names of her children, Winfield, Jordan and Davis, appear as surnames in the family records of the 17th and 18th Centuries. Quite honestly, the publication of this entire book was delayed a year as I struggled with clarifying family connections from one generation to the next in the 17th and 18th century. That struggle will be made clear to you as I convey the information I have thus far uncovered.

Davis family history is the most complete volume of early American colonial history found in our family library. To say it isn’t Smith family history is to make light of the importance of every woman who surrendered her maiden name, took on the role of wife and mother, and contributed one half the DNA required to jump-start the next generation of munchkins that populate Earth.

In the Chronicles for Shelley, my father spoke of a massacre of Davis family members. I have found several, many times great grandparents being butchered in massacres or abducted and swept away from their children. Each time I gird my teeth in pursuit of the story.

Hezekiah Stilley (1763-1840), who grew to adulthood during the American Revolutionary War, married the proverbial girl next door, Sarah Davis, daughter of William Davis, Esquire. The ‘Esquire’ is important in terms of separating this William Davis from several other men of the same name that will surface in the narration that follows. It was a title granted to William in legal documents that appear in the archives of North Carolina and Hyde County in particular.

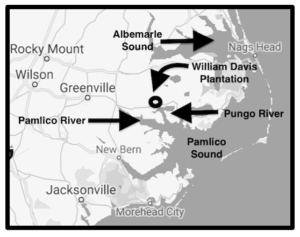

Hezekiah and Sarah are identified in the 1790 census of Hyde County NC. They are not listed in the 1800 census. With the Stille DNA flowing in his veins Hezekiah did what Stilles did over the course of two centuries. He packed up his family belongings on the Pungo River and headed north and west into the distant rolling hills of southern Illinois, where he would be among the first American citizens to establish a homestead.

Just as Olaf Stille had been accompanied by his brother Axel when coming into colonial New Sweden, Hezekiah was joined by his brother, Stephen ‘The Elder,’ as he was known in the hills of Makanda, Illinois. Stephen was an ardent preacher and one of the first American preachers to establish churches and church buildings in southern Illinois. Hezekiah’s 2x great grandfather, Olaf Stilley, had been quite content to live amongst the Native population in Delaware in 1650. Hezekiah demonstrated the same preference for Native company on the western edge of the expanding American civilization in the region of the Mississippi River.

Pedigree Chart 10: The Stilley / Davis Lineage

Once again, Hezekiah and Sarah Davis Stilley were the great grandparents of Jane Stilley, my great grandmother. The chart posted above reflects the extent of my knowledge of the Davis family in our tree on January 12, 2015. I know that date is accurate because my internet history shows a spike in searches using the keywords ‘William Davis,’ ‘Hyde County,’ ‘North Carolina,’ and ‘Psychological services available in northern Wisconsin.’ The research drove me bonkers!

Grandfather, Lebanon Faris Smith appears to the left as the son of James M. Smith. Please look to the far right where I show William Davis Esq and ‘Elizabeth Davis?’ as the parents of Sarah Davis. In the year 2015 I did not have information identifying the mother of William Esquire’s children. His wife, Elizabeth, at the time of his death, was not (as I suspected) the mother of his children, although every online tree has dubbed her as such. Thus, the question mark in 2015. It took two years of intermittent research to iron out William Esquire’s relationships.

When I initially asked myself, “Who was Sarah Davis?” I had no idea I would uncover the early history of colonial America from Maine to North Carolina. Uncovering the lineage leading to Sarah Davis became entailed, entangled and mind boggling. Please note William Davis Esq was also the father of Rebecca Davis. Rebecca was also my father’s 3x Great Grandmother, by virtue of being the mother of Lydia Rogers, wife of Davis Stilley. Rebecca gets less ink in these pages simply because her spouse, William Rogers’ history is dubious, at best.

Finding Sarah and Rebecca Davis’s ancestors was not an easy task. Finding documentation was a hit and miss proposition. Incomplete files, missing paperwork, theft of records and deliberate destruction of property over the centuries required more than the usual scrutiny I take when connecting the dots. Past generations of angry men burning courthouses during times of war and rebellion contributes to a condition I have coined as Darwin’s Syndrome among present day family historians. As I have invented the syndrome, I will also illustrate it for you:

Darwin’s Syndrome: The unfortunate victims of the syndrome experience high levels of anxiety when unable to find a missing link in their family tree. They send out pleas for information. They promise to trade valuable findings on an obscure person as if dealing in rare stamps or baseball cards. They offer info from a rare, great aunt Mildred’s family Bible, as if it were the best solution for solving the Rubik’s Cube of Life. These poor souls become reclusive in their social lives and panic like a father who has lost track of a young child on a foreign beach or in a shopping mall in Chicago. These victims wander like feral dogs in a Bangladesh refuse dump searching for one scrap that will sustain them in their effort to complete a branch of the family tree. One can only go back so far, and folks aren’t going to believe you, for a variety of reasons, when you say you can demo your descent from Adam and Eve.

DNA test results have helped family researchers when foraging through the forest of deeds, wills and documents available from the 1600 and 1700s. Grown men, with tears in their eyes, and church ladies too, have been seen emerging from the darkness of their computer dens, pounding their chests like one of Jane Goodall’s chimpanzees once they are able to identify the name of a long lost great grandfather. Then and only then can they escape the grasp of what is ‘Darwin’s Syndrome.’

There is one other way to combat the effect of the Syndrome and that can be found in the small shed behind the remnants of Wilbur Rancidbatch’s barn in Shepley. I’ll say no more.

Gen 8: William Davis (1725-1802)

Sarah Davis, the daughter of William Davis, Esq is identified in his will dated 1802. We can begin our search with him. Per census data William Davis, Esq. resided in Hyde County NC and was part of a North Carolina militia serving under the command of William Satterthwaite, a longtime friend and neighbor. Military payroll records indicate that our William served as an officer in the Revolutionary War. He rose through the ranks quickly to become a high-ranking officer.

William’s plantation was profitable as revealed in the List of Tithables (taxpayers). The census records for Hyde County, NC for 1790 and 1800 reveal that he possessed seven slaves, sometimes eight. There were plantations with more slaves, but not many. Certainly, the Gibbs family down the road ran a much larger operation with five times the number of slaves. So, if we can measure wealth in the number of people one owns, and the amount of tobacco one can produce we might call the man wealthy. That is, of course, one disturbing way to measure wealth.

In his will, Davis assigned his ‘manner plantation’ (sic) to his son Jesse. The properties of William Davis were located along the Pungo River. The Pungo, marked with a ‘thumbtack,’ feeds into the Pamlico Estuary which empties into Pamlico Sound. The river system drains the Great Dismal Swamps to the north. The next estuary to the north is the Albemarle Sound, on the shores of which William’s ancestors lived near Edenton in the 17th Century.

Willliam Davis and brother John held lands along the Pungo River. Their deeds reference Tarklin Creek, Dipp (aka Deep) Creek and Ruttman’s Creek. The creeks empty into the Pungo at the mouth of a canal that was first dug centuries ago and improved in the 1950s. The Wilkinson family lived on the south side of the canal. Hyde County documents identified the many citizens who invested in the canal which provides an inland waterway connecting the Pungo/Pamlico river system with the Alligator River to the north.

I have yet to find any evidence that the Davis men lost any livestock to alligators, although a few area golf courses report golf balls do go missing or are simply left by players who decide to play a Mulligan, a second shot, and allow the alligator to consume the golf ball, should they so choose.

William’s Last Will and Testament

The abstract for the will of William Davis can be found online in the Hyde County NC Will Book #3. Entry 54 reads as follows:

“Item 54: Apr. 10, 1802 – Will of William Davis – Wife: Elizabeth; sons: John, Jesse, Richard, William; daughters: Sarah Stilley, Lydia Davis, Wineford Winfield, Rebecca Rogers’ 3 orphan children; friend Frederick Allen.”

His will is also found in the Appendix of this book. The abstract identified William’s wife, at the time of his death, as Elizabeth. It provided no clue as to her maiden name. Not unusual, but a mystery begging to be solved. He had 3 daughters living at the time: our esteemed Sarah Stilley, Lydia Davis and Wineford Winfield. Two daughters Rebecca (Rogers) and Mary (Allen) predeceased William. We know this becauseRebecca’s share of her father’s estate was allotted to ‘three orphan daughters.’ We learn more about Mary while tracking down other leads.

William also identified a “friend,” Frederick Allen who appears to have been a grandson, the son of William’s deceased daughter Mary (d 1801) and her widowed husband, John Allen. Mary’s name does not appear in the will. She predeceased William. The application of the term “friend” when referring to grandchild, Frederick, is unique. John Allen, later found to be Fred’s father, acted on behalf of William’s estate in a courtroom drama found buried in the archives.

Because there were several adult males named William Davis in the region, it became important to sort through every detail of this abstract and William’s Last Will and Testament which can be found online in Hyde County, NC archives. I have appended it to the rear of this book.

William assigned his lands to various sons. His carpenter and farm tools were equally divided among his four sons and his blacksmith tools went to his son Richard. One cannot assume that William was a blacksmith by trade. It was not unusual for a pioneer to be a jack of all trades: blacksmith, bricklayer, stone mason, road builder, carpenter. Evidence when compiled indicates that William occupied a high-status position in the Carolina aristocracy.

Amid the discussion of his various possessions Davis addressed the distribution of his slaves; one of whom became very important in opening the door to the history of our family. The population census of 1790 indicated that William owned 8 slaves. At the time of his death we count 7. In 1803 he distributed those human beings, along with his cattle, furniture and tools as follows:

He gave “my slave Jemima, to my beloved wife, Elizabeth, to her and her heirs forever.”

‘Forever’ was a long time. It was as if folks were handing down a good shovel or kitchen table.

— To my son, John Davis my negro boy named Gabrel…

— To my son William Davis a negro boy named Joseph…

— To my son Richard Davis a negro boy named Moses…

— To my daughter Lydia Davis a negro girl named Kesiah, to her and her heirs forever.

And then, to drive the point home that a black human being was chattel, the decent Christian plantation owner did “lend my negro woman named Cate to my beloved wife during her life and afterwards I give her to my son Jesse Davis, I also give to my son Jesse my negro woman named Judith and my negro girl named Silard.”

If I understand colonial American history correctly, a man could keep human beings out back in shanties and shackles, work them for a profit, and bind them, brand them and beat them, if necessary. But, if that same man missed a Sunday morning church service he could find himself in a court of law, paying a fine with tobacco as currency and held up to public ridicule. Does that make sense?

I must ask the heart wrenching questions here: Was William breaking up a family when he apportioned his ‘property?’ It might be assumed that Judith and Silard were mother and daughter. But what of the young boys who were doled out: one here, one there? Were they Judith’s sons? Was Cate a mother to one of the boys? Was Jemima the mother of Gabrel? Moses? Joseph? Who did Kesiah leave behind when she was handed over to Lydia Davis? Or, were these children all unrelated? Had they already been separated from their mothers in the stockades of Charleston Harbor or in the Gambia of Africa?

Several pieces were falling into place in my search for the parents of Sarah Davis. I assumed I had found her father and mother, William Esq and Elizabeth. I was not anticipating the curve ball that was about to be tossed in my direction.

There were estates found in the archives that sometimes required an inventory and a court mandated division of the estate. Such was the case with the estate of William Davis, Esquire. The Abstract for the Division of William’s Hyde County Estate reads:

“Item 73: June 7, 1803 – Division of the estate of William Davis, Esq’r., dec’d. Heirs: widow (not named), Jesse Davis, Richard Davis, Oden Wilkinson & wife. Returned to court by William Clark, Esq’r., commissioner.”

This “Division” offered a few new twists. William was now referred to as “Esq’r” short for Esquire, a term denoting his rank in colonial society. Esquire historically was a title of respect accorded to men of higher social rank, particularly members of the landed gentry above the rank of gentleman and below the rank of knight. This designation would help me separate our William from others of the same name.

The name “Oden Wilkinson and wife” appear. Who was Oden’s wife? Did she have a name? Why did Oden and wife attend this court session? What interest did a Wilkinson have in the distribution of property? Was Oden a son-in-law? Was an unresolved debt to the Wilkinson family at hand?

William’s wife, Elizabeth, was identified only as ‘widow.’ No document has identified her as a mother to any of the children. She was not named as an executor of the will.

My confusion regarding William’s wife, Elizabeth, was compounded by the discovery of the abstract for her 1814 Last Will and Testament found as Item 710 in the Hyde County Will Book #3.

“710: Feb. 8, 1814 – Will of Elizabeth [x] Davis – Son-in-law: William Davis; Daughter: Dianna Davis; Son: Stephen Carter; Grandson: Solomon Carter; Grandson Fredk. Allen’s daughter Betsy Allen; Grandson Fredk Allen’s son Jesse Randolph Allen; To: Hannah Paul, Ezra Paul, Sukey Paul, Arcada Paul, & Redmond Paul (no relationship given for the Pauls); Executors: Son-in-law Wm. Davis & Frederick Allen.”

“Son-in-law: William Davis”? Why was Elizabeth including William Davis Jr in her 1814 will as a ‘son-in-law?’ She should have claimed William Jr as her son or, so I wrongfully assumed. The designation son-in-law had two meanings in 1814. It implied that a man married someone’s daughter and became a son-in-law to her parents, as it does today. It could also mean ‘step son’ (son by law). Elizabeth was clearly saying she was not the birth mother of William Junior. Question: Was this Elizabeth Davis the widow of William Davis Esq? And where were all of William Junior’s siblings? This Elizabeth failed to mention what I thought were her children. Instead, she mentioned a daughter Dianna Davis. There was no daughter named Dianna in William Sr’s 1802 will. The Carters and the Pauls were all mentioned in the will of William of 1802, but our William did not claim any Carters or Pauls as his children or grandchildren. Finally, William Esq had referred to Frederick Allen as a ‘friend’; Elizabeth referred to him as grandson.

And then it hit me. I was studying the Brady Bunch. Two families, the Davis and Carter families, had merged in the latter decades of the 1700s. William Davis came into a marriage with Elizabeth Carter at a point in life where each had adult children. William Davis provided for his children in his will and left nothing to his stepchildren: Stephen and Dianna Carter. Their father had provided for them in his will and they were adults at the time of our William’s passing and they (Stephen and Diana Carter) were well established.

I realized I knew nothing regarding the mother of William’s children. I still did not know Elizabeth Carter Davis’s maiden name. I also did not understand the inclusion of the Paul family or Frederick Allen in the wills. The Pauls (Jacob and Ezra) were witnesses to Esquire’s will. I had questions without answers. Was the surname ‘Paul’ a variation on the name ‘Powell’ which did occur in Coastal Carolina? Would it even help to know more about the Paul family, or would it cause greater confusion?

Elizabeth Davis identified two children in her will: Stephen Carter and Dianna Davis. As she was not mentioned in Esquire’s will, Dianna was not Esquire’s daughter. Elizabeth names William Jr as her son-in-law. Conclusion: William Jr married his stepsister, Dianna. Scandalous? Not really! We find cousins marrying cousins and step kids marrying each other throughout history. It’s bad for the teeth, but hey, it was a very small world and there weren’t a lot of people available for marriage ceremonies of any kind.

I kept digging for evidence that would lead me to Esquire’s first wife or wives. I assumed the Elizabeth in Esquire’s 1802 will was Elizabeth Carter Davis (d 1814), a second or third wife of our William. I also assumed Esquire’s son, William Jr, did marry his stepsister, Dianna, thus becoming Elizabeth Carter’s son-in-law. That would explain why no other Davis children benefitted from her estate.

And then life got complicated. I found an Account for the Sale of the Estate of Elizabeth Davis (d 1801). Found in the Hyde County NC Will Book #3, entry 49 reads as follows:

“Item 49: Account of Sales of the estate of Elizabeth Davis, dec’d., sold by James Warner, adm’r., on June 13, 1801.”

Was William’s previous wife also an Elizabeth? If so, his marriage to Elizabeth Carter was of very short duration! Was this Elizabeth (in the 1801 entry) the Elizabeth named in William’s 1802 will? Had he died so quickly after her 1801 death that he did not have time to alter his will? If the 1801 Elizabeth had been our William’s wife, why was it necessary for James Warner to sell off her estate prior to William’s death? The standard practice at the time would have placed her possessions in William’s hands. There were other Davis families in the area. This Elizabeth (d 1801) may have been the wife of one of William’s brothers or cousins. Lord knows, he had a bunch of them, as we shall see.

I pushed back from my desk many times during this investigation. On this push back, I pushed a little too hard, out of frustration, and tumbled onto the floor. There was an awkward moment in which I struggled to get my body into a position that would allow me to rise from the floorboards. Arthritis, a hip replacement and a diminished core can do that to a senior citizen. I suddenly understood the commercial, “I have fallen, and I can’t get up.” I finally got to my feet, enticed by the thought that a bag of doughnuts was nearby.

I got on the elliptical with a handful of doughnuts and I ran for miles on the treadmill with another handful of doughnuts. I smoked a few cigars and downed a lot of coffee. I was going to get healthy if it killed me. Two women, Elizabeth Warner and Elizabeth Carter gnawed at me, one had my ankle, the other my wrist. I knew the first of these two women was a Warner at birth, because James had been identified as her brother. I shuffled among the index cards and Dove chocolate wrappers and found a pertinent page. The 1814 Will of Elizabeth Carter Davis had been lost among the documents on my desk.

I stared at the page, reading it again and again. I read it slowly to myself, aloud. I read it quickly and quietly. I read it with a French-Canadian accent, and I tried translating it into broken Gaelic (the Irish kind, not Scot). And then it jumped out at me; the name ‘Jemima.’

Elizabeth Davis, deader than a doornail in 1814 gave her dear daughter Dianna a slave: “and to my daughter Dianna my slave Jemima.” William’s 1802 will had dictated that his wife Elizabeth would receive a slave or two. He gave “my slave Jemima, to my beloved wife, Elizabeth, to her and her heirs forever.” And there was Jemima, in 1814, moving from the ownership of Elizabeth Carter Davis to “daughter Dianna.” I would love to meet Jemima. I think I could learn a lot from her regarding the inner workings of the Davis and Carter households.

I walked back onto our deck again. “Bitch,” I whispered into the smoke curling away from my cigar. I wanted to throttle Jemima’s owners. I didn’t know Dianna or Elizabeth Carter Davis, or William Davis. They may have been wonderful people. He was an ‘Esquire’ after all, not nobility, but the next best thing in the aristocracy of the old South. In the grand scheme of things, it wasn’t all that long ago. No wonder we have such a difficult time in this 21st Century country with all issues related to race and wealth. I turned off the laptop for several days and did stuff, other stuff, stuff that needed to get done: install a heater in the wood shop, a sump pump in the basement and an external hard drive on the laptop to add ample storage for the files that seem to be multiplying at night when I turn my back on the critters that live inside this infernal machine.

Miss Jemima helped me understand that Elizabeth Carter Davis was indeed a second wife of William Davis, but not the mother of any of his children. It took a bit more leg work and a few more drams to identify Elizabeth Davis (d 1801). I refer to this Elizabeth as Elizabeth Warner and the second Elizabeth as Elizabeth Carter.

My years of exploring Smith family roots had introduced me to the great wealth of the Carter clan of Virginia, a tentacle of which had moved into Carolina. Warner family members were found in my wife Nancy’s lineage. My wife shares Augustine Warner (1610-1674), her 9th great grandfather, with George Washington. Auggie was George’s great great grandfather. Auggie seems like the kind of guy we could invite up here for ‘two or three beers’ and some clay trap shooting. I’d keep Blind Billy on a short lease but ask if we could borrow his Luger Red Label.

I would be remiss if I didn’t take a little time to enjoy my day and smell the roses. I ended my search for the mother of William’s children by jotting several notes on an index card:

Who gave birth to all of William’s children? How many wives did William have prior to Elizabeth Carter Davis? To whom did the Paul children belong? The mere fact that I can’t find the surname ‘Paul’ in any Carolina records at all, tells me something is amiss. Had someone responsible for transcribing documents turned ‘Powell’ into ‘Paul’? And what of Frederick Allen? Who was he and how did he end up in Illinois with Hezekiah Stilley?

I added one more note to the page, a question: ‘Who was Wineford Davis Winfield and why did that name sound so familiar to me?’ And then I held the hot coal of my cigar up to the edge of the index card and torched it. I could hear the ancestors screaming obscenities, but this is a family rated text.