A Migration Route: The Wilderness Trail

Blazed by William Bailey Smith and Daniel Boone

William Bailey Smith (1737-1811) and Daniel Boone: Wataugans

Father’s 4x Great Uncle and Brother of Peter Smith of Round Hill

Every family tree has a rock star; someone who defies reality; seems other worldly, Orwellian by nature; a regular sort of Forrest Gump. Rule 46/372 Section B paragraph 22 in the now defunct Grizzled Veteran’s Handbook states clearly that, “a person living in the 21st Century cannot claim that he or she is related to ‘someone famous’ from the 19th Century if the ancestor claimed as ‘famous’ was not an iconic figure at the time of his or her death, nor made famous by the authors of the time period in which they lived.” Ok, I made the rule up. But the fact is, William Bailey Smith shows up in a lot of deeds, peace treaties, territorial contracts, military records, government files and war records. He just failed to get into our history books.

Let me introduce you to Uncle Wm Bailey Smith. He is described in literature as “a tall, rollicking, unstable bachelor, energetic and brave, but with quite a turn for embellishing the facts.” He was the Indiana Jones of his generation. Google “William Bailey Smith and Daniel Boone” together in one search. Those are the key words. And Bingo! There’s Uncle Bailey, brother of Peter Smith of Round Hill. And what is he doing in those first few Google hits? Dang Nabbit! He is working with Daniel Boone, going up against Blackfish, fighting for Boonesborough, and saving Boone’s daughter (Jemima) from captivity at the hands of the Natives who had kidnapped her. Not bad for starters. There’s more! This guy really deserves his own movie. I picture Matthew McConaughey as Bailey.

William Bailey Smith (1737-1811) is my 5th Great Uncle. He was born on the banks of Bull Run, the son of James and Elizabeth Taylor Smith, and grandson of Peter Smith of Yeocomico (d 1741). Bailey, as he was known, carried the surname of his grandmother, Mary Bailey. The Bailey name was well established in the Virginia Colony. It is found in the early records of Jamestown, as well as Westmoreland County VA. Mary’s ancestors are identified in our family tree. Landmarks along the Virginia highway point toward the Bailey homestead.

Bailey Smith remained single for his entire life. There is no evidence that he was a lothario or the father of unwanted children. He lived his life in the vein of the famous Jamestown hero, Captain John Smith. Bailey was married to adventure and exploration. While Captain John Smith, no known relation, was married to the sea, Bailey was wedded to the land, to the great wilderness beyond the Blue Ridge Mountains. His adventures are well documented, and it is possible to develop a historically accurate portrait of the man and his contribution to the growth of America from coastal colony to inland empire.

The work of Bailey Smith brought him into close professional and personal contact with Daniel Boone in the construction of the Wilderness Road, the deeds bartered with the Cherokee’ of Watauga, the skirmishes and battles of the infamous “Indian Wars,” peace treaties, and the development of frontier fortresses including Boonesborough KY. Reviewing his exploits in a thumbnail sketch will be difficult, but worth a shot. I find the guy’s legacy fascinating, every bit as interesting as that of Daniel Boone. Bailey apparently lacked a PR agent, refused the limelight and preferred anonymity.

Bailey acquired a part of his father James Smith’s estate in Clifton, Fairfax County Virginia, when his father James died in 1749. Bailey sold his interest in that estate and joined his brother Peter in Caswell NC. Caswell was organized in 1777 at which time it was removed from Orange County. Bailey and Peter were part of the Great Migration of pioneers settling into the rich soils and forests of the Piedmont. Bailey Smith’s historical mini series begins in Watauga.

George Ranck, author of Boonesborough, writes the following:

“The Spring of 1775 arrived with a clamor for American freedom and independence. The hour had struck for the permanent settlement of Kentucky and in widely separated regions the hearts of unconscious instruments of fate had been fired for the work. But in no American colony was the interest in that distant forest-land keener than in North Carolina and in no place in North Carolina was it so conspicuous as in the little frontier settlement of Watauga in what is now East Tennessee.”

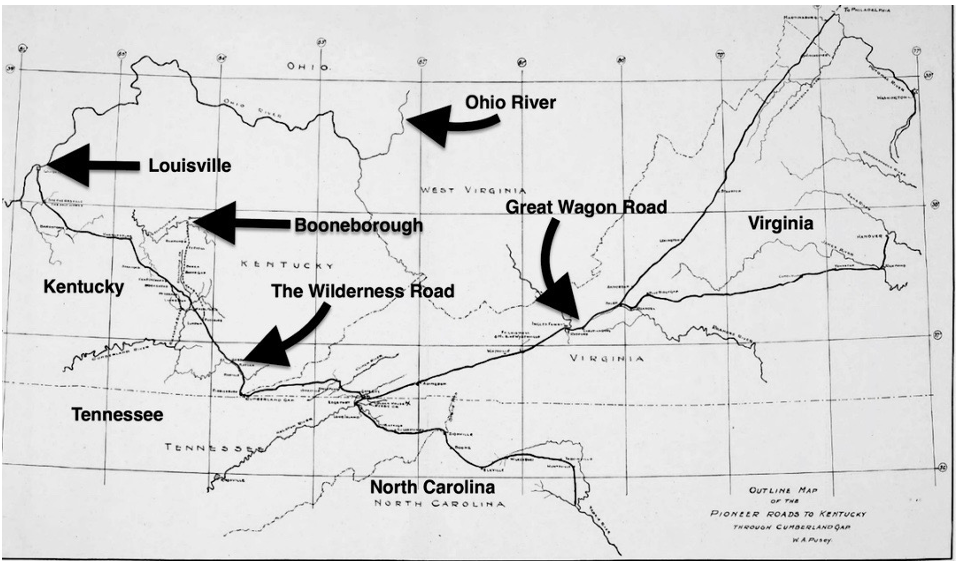

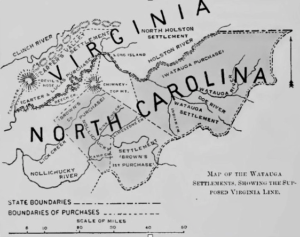

The Watauga Settlement (black dot) was an anomaly. Prior to the American Revolution, North Carolina claimed all of Tennessee. Directly above Tennessee we find Virginia which included lands in Kentucky at the time of the Watauga Association. Only a handful of Caucasians knew what was beyond the Blue Ridge Mountains. Long hunters like Joseph Martin had traversed the ridge and knew the hills went on forever. They knew the Ohio River flowed west and the ‘Great River’ known as the Mississippi ran from north to south into the Gulf of Mexico. The French had been going up and down the ‘Great River’ since 1672, when Marquette and Joliet first laid their canoe out on the water and said, “Let’s do this!” It was 150 years later, and Bailey Smith was chomping at the bit to become a land baron in a new land.

The Watauga Settlement (black dot) was an anomaly. Prior to the American Revolution, North Carolina claimed all of Tennessee. Directly above Tennessee we find Virginia which included lands in Kentucky at the time of the Watauga Association. Only a handful of Caucasians knew what was beyond the Blue Ridge Mountains. Long hunters like Joseph Martin had traversed the ridge and knew the hills went on forever. They knew the Ohio River flowed west and the ‘Great River’ known as the Mississippi ran from north to south into the Gulf of Mexico. The French had been going up and down the ‘Great River’ since 1672, when Marquette and Joliet first laid their canoe out on the water and said, “Let’s do this!” It was 150 years later, and Bailey Smith was chomping at the bit to become a land baron in a new land.

The first permanent white settler in what is now Tennessee was a guy named William Bean. He settled on Boone’s Creek in 1769 near where it flowed into the Watauga River. Communities like Nolichucky, Carter’s Valley, and North Holston sprouted up in places where a river might afford a mill, or a crossroad might be found or a ford in the river made. Many of our folks arrived via the Shenandoah Valley through western Virginia. Others, victims of the failed Regulator Rebellion (1771) in North Carolina came into Watauga from the east, finding gaps in the mountains that would allow a cart, wagon or simple man on horseback to pass.

The folks of Watauga understood how far removed they were from the colonial capital cities of Williamsburg VA and New Bern NC. They were separated by more than miles of course. Anyone who has driven in hill country, as in West Virginia, and the Carolinas understands how tedious a short drive can become, mounting hills, descending into steep valleys, winding up one ridge and down another. Civilization was a distant concept. A colonial militia was not present to protect the common man or police the renegade. The idea of dialing 911 had not yet been conceived. Settlers became their own militia and alarm systems required racing through the woods for help. The kill or be killed concept was in vogue. There were numerous Old Testament Christians the invoking the name of God and preaching, “An eye for eye.”

The Wataugans organized their own government, militia and judicial system and titled themselves the Watauga Association. The Wataugans established what amounted to the first white, autonomous bureaucracy in the British colonies. The Watauga Association (1772) cloned the Virginia legal system replete with commissioners, court cases, legal documents, and deeded properties. The settlers focused on the practical needs of routine government. They were more interested in self-preservation than independence.

Folks in these hill country settlements believed they resided in Virginia. They were a bit off in their estimate and it created problems for the British, for Virginia, North Carolina and the Cherokee. A survey revealed that of these new settlements, only North Holston was in Virginia. The remainder of the settlements were part of North Carolina’s western claims— land guaranteed by the British to the Cherokee Nation in the Treaty of Lochaber (1770). Colonial governors in Virginia and North Carolina were obligated via loyalty to uphold the British law and the terms of the Lochaber Treaty. The treaty not only defined the lands promised to the tribe but also reinforced the 1763 Proclamation that prohibited any colonist from purchasing land from the Native population. The British told the Watauga settlers to pick up their home furnishings and head north to North Holston and let the Cherokee have their promised land. The treaty had been put in place to keep the Native population from harassing the colonists.

In a town meeting several locals presented what amounted to an early version of a Powerpoint presentation, demonstrating the hardships they encountered, the hazards they faced, the homes they had constructed, mills maintained, and investments made in terms of sweat equity. Not too many were eager to move. So, they did what any normal person would do, they entered into a 99-year lease contract with the Cherokee. This is where our ancestors Bailey Smith and Buckspike Williams (Nancy’s family) came in to play. Buckspike was a multidimensional character, capable of wearing many hats. In this instance he worked as a go between, maintaining peace among the disparate parties and at the same time monitoring events, spying. Bailey was at the conference table, brokering the deal. The pioneers of Wautauga were shrewd operators.

The Wataugans put an interesting spin on their effort: 1) “Hey! We thought we were in Virginia and therefore legal,” and 2) “Gosh! We aren’t buying land from the Cherokee. We are leasing. So, hey! Leave us be.” Expecting a battle from either the British or the Cherokee they refused to budge. They moved to the safer confines of the Watauga settlement, behind the timber palisades that were the hallmark of colonial settlements in Jamestown and Plymouth Colony. The Brits were not happy. Insubordination was becoming all too commonplace among the colonists. The British Proclamation of 1763 had outlawed the purchase of Native land by anyone other than the British government. The Wataugans were operating beyond the law and assumed that they might also be beyond the reach of the British. One hundred and fifty years later, Theodore Roosevelt would cite the Wataugans as great patriots who set the stage for the colonial revolution that was soon to follow.

The Virginia and North Carolina colonial governments, seeking to avoid a bloody confrontation with Wataugans, and the Cherokee, organized the area as Washington District, treating the region as a county, an extension of North Carolina. Wataugans were offered protection under the law and were also expected to abide by the law.

Henderson’s Transylvania Purchase

With sabers rattling on the east coast of the colonies and British attention diverted to patriot challenges to authority in New England the time was ripe for a land grab in the hills of Appalachia. One of the eager speculators was a cat named Richard Henderson, for whom Bailey and Daniel Boone would work as trail busters, ‘Indian fighters’ and guides. Whether Henderson was taking a stab at establishing a small North American country to the west of the colonies, independent of England or a 14th colony remains unclear. His strategic plan reached far beyond Watauga into the very heart of what would become Kentucky. For several days in mid-March 1775, Henderson, with Bailey Smith at his side, negotiated with leaders of the Cherokee Nation. They secured an agreement by which the Cherokee exchanged their claim to the Cumberland River Valley and most of Kentucky (20 million acres in all) in exchange for 10,000 pounds sterling of trade goods. If the 10,000 pounds sterling was in chocolate my wife would say the Natives got the better end of the deal.

In August of 1775, Richard Henderson and his associates declared themselves owners of all the territory south of the Kentucky River, which comprised more than one-half of the present State of Kentucky. The Cherokee Indians, on that date, deeded the land to Henderson and Company. William Bailey Smith was among those who negotiated and witnessed the transaction.

Bailey Smith’s role in the Transylvania Purchase was one aspect of his work for Henderson. On Christmas Day of 1775 Smith became a front man for investors, marketing Kentucky properties. Henderson’s pamphlets circulated, advertising for “settlers for Kentucky lands about to be purchased.” Henderson and Boone agreed that the first settlement should be made at the mouth of Otter Creek on the Kentucky River (the settlement later known as Boonesborough). With all the land in the ‘Caintuck hills’ at his disposal, Henderson was eager to open a road and move pioneers into his domain. This was the model for how land speculators operated.

Bailey Smith surveyed the land for Henderson and organized the route. On March 10, 1775, Boone and Smith and 30 armed and mounted Scotch-Irish axmen began felling trees, turning Native hunting trails into horse paths wide enough for wagons, and early versions of the Suburu, heading for a destination 200 miles away.

On March 28, Henderson pulled a move that would catch Boone off guard. He left Watauga and started toward the land of his dreams. His expedition included 40 mounted riflemen, numerous Negro slaves, 40 pack horses, a train of wagons loaded with provisions, ammunition, material for making gun powder, seed corn, garden seed, a drove of bees, etc. Henderson was accompanied by four other members of his Company: his brother Samuel, John Luttrell, and the Harts. William Bailey Smith was relieved of his work on the front edge of the pathway and was called upon to accompany Henderson as a surveyor. Henderson expected Smith to refine every aspect of the trail as they moved forward, ensuring that the preliminary work conducted by Boone’s contingent was now turned into a highway wide enough for wagon travel.

Once the road was opened and Boonesborough established, Bailey Smith continued his work for Henderson. As a military Captain, Smith was one of those chiefly responsible for the defense of the Boonesborough fort against Indian and possible British attack. He rescued Jemima Boone (Daniel’s daughter) and the Callaway girls when they were captured by First Nation warriors. At different times Boone, Smith, and Richard Callaway negotiated with the Natives.

Henderson’s Transylvania Purchase was not popular with all elements of the First Nation. In fact, it created some serious negative vibes within the Cherokee Nation. A militant faction of the tribe, under the leadership of the Chief’s son, Dragging Canoe, broke with his elders and sought to reverse the sale and maintain control of Cherokee hunting grounds. This growing faction aligned itself with the British during the American Revolution and raised hell with American war efforts.

The threat of Cherokee attack was real and Wataugans appealed to both Virginia and North Carolina for protection. North Carolina agreed and created the Washington District to include all Carolina lands west of the Blue Ridge into lands as far as the eye can see. The Cherokee attacked in 1776. The Wataugan’s retreated to their fort and withstood the siege. In 1777 Washington District became Washington County, and the Wataugans gave up any urge for independence. The Watauga Association was no longer necessary. The Transylvania Purchase was nullified by both Virginia and North Carolina colonial governments on the premise that the purchase violated the Proclamation of 1763 and Treaty of 1770.

On December 7 the State of Virginia designated Kentucky as a county within the state. The new county included what had once been Henderson’s Transylvania Purchase. Boonesborough was thus a wilderness settlement at the extreme west end of Virginia. Henderson and his investors were compensated for their loss with 200,000 acres of land below the mouth of Green River. The present city and county of Henderson are on this tract, and it was here that William Bailey Smith, heirs of Luttrell, and others finally settled.

Smith’s work at Boonesborough came to an end, but he continued in the employ of Henderson who was now focused on developing a kingdom in what is today Tennessee. In the Spring of 1780, food and grain was desperately needed at the half-starving community of French Lick, present day Nashville. Henderson was shipping foodstuff the entire distance by water in log barges traveling along the Kentucky and Ohio Rivers and up the Cumberland to French Lick. The fleet was put in the charge of Major William Bailey Smith.

Wataugans did play one more very significant role in the American Revolution. They organized themselves into a militia known as the “Overmountain Men.” The moniker made sense. They lived beyond the Blue Ridge, over the mountain. These fierce long hunters were accustomed to survival tactics and skirmishes with an enemy. They focused on the British redcoats. There are many historians who give these men (and women) a great deal of credit for the eventual American victory in the Revolutionary War.

The Overmountain Men gathered at the Sycamore Shoals of the Watauga River. They crossed over the mountains, attacked and defeated British Colonel Patrick Ferguson at the Battle of King’s Mountain in 1780. It was a battle which Thomas Jefferson referred to as ‘thee turning point in the war with Britain’. We had relatives on the King’s Mountain battlefield. One of them, a Whittington great grandfather, died in the bloody forest in the arms of his son, Buckspike Williams. Verifying this death scene has proven difficult. Buckspike is not listed among the Overmountain men who served in battle at Kings Mountain. Errors are a common factor in family histories. This may be one of them. There were others of our ancestors who were also in the battle. We will meet a few of these characters as we climb this tree.

Bailey Smith served the patriot cause in the Revolutionary War on the western frontier in both the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys.

William Bailey Smith and Brigadier General George Rogers Clark

General Clark arrived in Kentucky in 1772 as a surveyor. He was among those opposed to Colonel Henderson’s Proprietary Government at Transylvania. Clark had visions of his own for the development of the region. He understood the important role these new frontier lands would play in the growth of America. In 1776, as a delegate in the Virginia Assembly, Clark strongly urged Governor Patrick Henry to be mindful of the need to protect the backside of the American front in the war with England. Kentucky settlements were frail, ill-equipped, undermanned and vulnerable to British and Indians in the Northwest Territory. Governor Henry heard Clark’s plan of attack and authorized the raising of an army to attack remote British forts and protect the western front. Clark received permission to proceed with his plan and chose the captains and lieutenants for his expedition and began recruiting. His diary says:

[January 2] “Appointed W. B. Smith major. He is to receive 200 men [on the Holston] and meet me in Kentucky the last of March.” “3. Advance Major Smith 150 pounds for said purpose.”

Clark wanted to raise 400 troops for his Illinois campaign, and he hoped Smith alone would pull 200 soldiers out of the Watauga area. Smith’s efforts were made difficult by a number of competing issues. The locals were more concerned about defending their homes in Appalachia and did not want to leave their families vulnerable while they went off to protect Kentucky pioneers. The federal government (Continental Army) was competing with Virginia state militia efforts and paying more for soldiers than Smith could offer. Smith did not reach his goal of 200 troops and his force, once it headed west, was running behind schedule, throwing off the timing of the entire campaign. Clark had to adjust his plans. When Smith’s troops arrived in western Kentucky, they heard Clark explain the nature of the task before them. Smith had been ordered by Clark to keep the invasion a secret. The Watauga men had no idea they were part of an invasion force. They expected to protect Kentucky villages from marauding bands of Indians. Many of them deserted in the dark of night and headed back to North Holston. Those who remained helped George Rogers Clark secure Forts Kaskaskia and Vincennes in the Revolutionary War.

Smith’s Role in Determining the Virginia and North Carolina State Line

No one knew at the time whether Virginia’s boundary line would strike the Mississippi River above or below the mouth of the Ohio. Confusion in the settlement of Watauga was just one example of problems that evolved as pioneers pushed westward into the hills of Kentucky and Tennessee. To put the issues to rest, both states (Virginia and North Carolina) sent Commissioners to survey the line to the west. Virginia Commissioners were Doctor Thomas Walker and Daniel Smith; those of North Carolina were Colonel Richard Henderson and William Bailey Smith. The Daniel Smith representing Virginia was not our Daniel Smith, a son of great uncle Thomas Smith, as I originally thought. Thomas Walker may be descended from the Walker family of Westmoreland, neighbors and relations of Peter Smith of Yeocomico.

William Bailey Smith finally retired about 16 miles from the site of the present city of Henderson, Kentucky, on a tract of land which he received from John Luttrell, of the Transylvania Company, in payment for his services. His residence was known as ‘Smith’s Valley,’ at the mouth of the Green River.

Within several years Bailey Smith played a role in several land acquisitions that set his siblings up for life. Presley Smith acquired 1,000 acres lying on Panther Creek, which fed the Green River below the land of William Bailey Smith, on the said creek and 1,000 acres of land for his brother Peter Smith in 1776. Nancy Smith Boggess, sister of the Smith men, acquired 1,000 acres on Clifty Creek in January 1783. We do not know if Peter Smith, who died at Round Hill in 1797, ever enjoyed his property in Kentucky. In the present day he would have hopped in his SUV on weekend trips to hunt and fish in the great outdoors.

William Bailey Smith died October 19, 1818, in Daviess County, Kentucky. Upon his death a will dated 1811, made in Ohio County, Kentucky was presented for probation by his nephew Moses F. Smith (a son of Peter Smith of Round Hill). Presley Smith, a brother to William Bailey Smith and Peter Smith of Round Hill, entered a suit in chancery claiming the will submitted by Moses, was a fraud. A lengthy proceeding ensued and after Presley’s death in 1819, Presley’s son W. B. Smith, Jr., kept the case alive in court. Moses F. Smith denied any charges of forgery. [20th Century family historian, Pearl Smith, uncovered the paperwork for this case in Circuit Court Equity File Box No. 17, in the Daviess County Court House at Owensboro, Kentucky.]

Presley Smith’s concern about Bailey’s will relates to the nature of the gifts: the will bequeaths $500 to nephew James Simpson Smith; $100 to William Wigginton Smith (both sons of William Bailey’s brother Peter), old slave Sinah to be set free; and balance of estate to Moses Smith. Witnesses: Richard Taylor and Jacob Shaw. Mentioned in papers pertaining to the suit were Nancy Smith Boggess and her children.

Since William Bailey Smith and his nephew Moses F. Smith both lived in Daviess County, and nephews William W. and James S. Smith lived nearby in Muhlenberg County, it seems likely that they had more contact with him than did Bailey’s brother Presley, who lived at a considerably greater distance in Washington County. A family feud regarding property is the third most common cause of stress in sibling relationships; topped only by control of the television remote and use of the bathroom. This charge of fraud against Moses Smith was, however, a rare example of infighting in the Smith tree. The dedication to court systems and a sense of justice found in newly opened frontier often thought of as the Kentucky wilderness was remarkable.

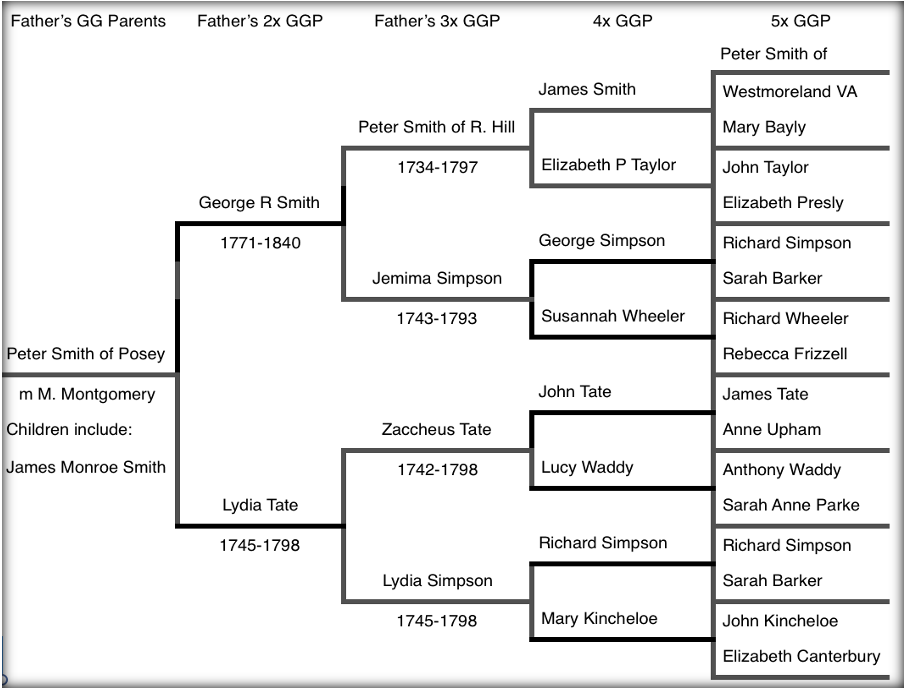

Pedigree Chart 6: From Posey IN to Westmoreland VA

James Monroe Smith (Leb’s father) is identified to the left, as the son of Peter Smith of Posey. The descent of Peter of Posey from George R. and Peter Smith of Round Hill is also apparent. We are traveling back in time on that Smith branch of our tree. We will circle back and learn about many of the allied families identified in this pedigree chart, including the Tates, Simpsons and Kincheloe clans. There are a few famous names hiding in that forest and a few not so famous characters who lived life on the edge.